Whenever my mother would talk to me about her thirty-five years of marriage to my father, she’d end on a familiar refrain: “I was always my own woman. And I was always my own man too. You see, I had to carry my own weight every day of every year, and I mean every bit of it.”

I understand what my mother says. Iran: it’s the country I was born in, went to school in, and have worked as a professional journalist in for twenty years; a country where authority, religion, and fate would have it so that even someone like my mother had to pull a permanent double shift as both a woman and a man throughout her entire adult life. I can’t say if, as a country, Iran is unique in this way, but I do know it is one place on earth that is emphatically this way—a place where women are in every measure equal to men, and in every measure not.

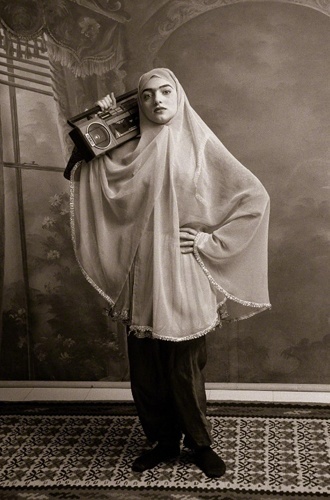

I had to dig deep into my backpack before I found the acetone polish remover and cotton pad that would save the day. My nail polish was hardly head-turning. After many days of dishwashing and cooking, the color was like a faded stain. I wasn’t going to tempt any man to his doom with seductive fingernails, but I was headed to see a cleric for an official interview at the Armed Forces of the Islamic Republic of Iran’s Division of Topography. Neither the cleric nor the Division of Topography would be amused at the sight of any color on me, faint or not. So I rubbed those nails with everything I had and then stuffed the sharp-smelling cotton in a pocket of my backpack. Next I put on a proper hijab; there was no way they’d let me in with a simple shawl. I secured it over my head so that no hair would show. As I prepared myself, the rest of the passengers in the taxicab barely gave me a glance. This, after all, was not an unfamiliar scene.

As I’d expected, the Topography Division had separate entrances for males and females. I took a deep breath and stepped inside. A woman wearing a chador asked what my business was there. I told her. She asked if I was sure that Haj Aqa was in today. “This is not a day he usually comes in.” I repeated that I had a 10 a.m. appointment with Haj Aqa and it was already getting late. The woman gave me another once-over. Then she said, “Your manteau is too short. You also have makeup on. No, you can’t go inside.” My manteau came below my knees and I wasn’t wearing any makeup. I looked at her. My cell phone rang; it was Haj Aqa himself. He wanted to know if I’d arrived. He was flying to Mecca later on that day and couldn’t afford any sort of delay. I told him that I was stuck downstairs at security and they weren’t letting me in. “They say I don’t look proper.” He was surprised, then became angry. He told me to wait right there and in a minute he was downstairs.

Until then I’d only known Haj Aqa from the articles he’d written. He seemed like a well-educated fellow, pragmatic and sensible, which was why I’d called to secure an interview with him. Now I watched as he turned to the woman at security: “This lady is coming upstairs with me.” The woman immediately sprang to her feet. “But Haj Aqa, her hijab is not proper. Her manteau is too short and she’s wearing makeup.”

This time he didn’t even bother looking at her as he commanded, “Come with me!”

The woman’s voice followed us out of security: “Haj Aqa, if anything happens, the responsibility is your own.”

What could “happen”? I wondered to myself as I followed the cleric to his office. What possible ignominy could a woman reporter standing a little over five feet two inches, looking positively average in a pair of gray sneakers, a dark green manteau, and a black headscarf wreak on the Topography Division of the military of the Islamic Republic of Iran?

When we were in his office I didn’t mince words. I asked the cleric, “Why are women treated this way at government offices? I mean, just because I’m not wearing a chador I’ll turn this place into a den of immorality?”

He was quiet for a minute, then said, “You know, the other day my car was stolen near Argentina Circle. I went to the local police station to put in a report. I could hear people behind me in line whispering among themselves. Would you like to hear what they were saying? ‘Whoever steals from a mulla is a saint!’ This is what they said behind my back. And I had no answer to that. Know why? Because people are angry at us clerics and they have every right to be angry. We haven’t been fair to them. Actually, we haven’t been fair to this country ever since the Islamic revolution. So to you I say, ‘You too have every right to be upset.’ But… don’t expect me to repeat any of this during our interview.”

“Let’s say I arrived for an interview at the college wearing pink nail polish. What would you think of me then?”

“Haj Aqa, I doubt there’s going to be an interview at this point.” I was looking at the puckered carcass of my professional voice recorder. Somehow the acetone pad that I’d stuffed in the backpack’s side pocket had eaten right through the gadget’s microphone. The thing was useless now, but I asked my question anyway: “You teach social psychology at the university. Let’s say I arrived for an interview at the college wearing pink nail polish. What would you think of me then? Would they treat me there like they treated me here today?”

He regarded me for a long time. It was as if he was trying to tell me something—I just tried to convey to you, a reporter, my honorable intentions as a man of the cloth and an official of the Islamic Republic. And still you have to be stubborn with me?

I met his gaze and thought, What do you expect from a woman, and a reporter at that, in this town? Any way you look at it, it’s this town that taught me to be ruthless. It’s this country that forces me to act as I do and ask the questions I ask.

He adjusted his turban a little. “If two years ago you’d come to my office wearing pink nail polish, I wouldn’t have thought well of you.”

Two years ago signified 2009, the year of the Green Movement, a time of vast street demonstrations and arrests. I pretended not to catch the significance of this and asked, “What’s happened since that time that’s made you change your mind?”

“Two years ago is just a number,” he said, playing along. “What I mean is that I’ve traveled a lot over the years. I’ve seen a bit of the world by now, but, more importantly, I’ve been reading a lot of history. I’ll tell you something, studying history clarifies a great many things.” He stared at my cell phone, which had begun vibrating without sound on the table.

“Haj Aqa, if the phone is a bother, I’ll put it in my bag.”

“You can go ahead and answer this one.”

It was my boss at the paper. He wanted to know when I’d be back at the office. With more than a hint of irritation I told him I was in the middle of an interview. He sounded apologetic, and said he knew where I was but he’d been forced to call me anyway. There was a pause and he added, “There’s a woman here. Says she won’t leave until she sees you. Says…”—another pause before he mumbled awkwardly—“She says you’ve been with her husband.”

I was born in the city of Mashhad, Iran’s most religious city—arguably more religious than the seat of clerical power in Qom because one of the twelve revered imams of the Shia is buried in Mashhad. Mashhad is a major pilgrimage center for Shia from around the world and a place where I never felt at home. Rather, it was Tehran, the capital, that I yearned for since the age of eleven when I read Somerset Maugham’s Of Human Bondage and discovered in my older brother’s biology textbook where babies came from. By the time I was fifteen, I had a map of the city that I’d stare at for hours. I would spread that map out on the floor of the barely 600-square-foot, blue-collar apartment our family of eight lived in and I would try to learn each twist and turn of the Iranian capital by heart.

When I finally arrived in Tehran for university, it was as if I’d always known the place. The museums, the spots our poets had written about, the neighborhoods where film sequences had been shot: they were mine now. This was my city. I quickly got a job at a no-name journal where I could make some pocket money and I walked everywhere.

“A woman, unlike a man, should have fear. But you have no fear, my daughter, and so I have fear for you.”

My father, always afraid for his daughter, would telephone and say, “Please don’t go anywhere by yourself!” When inevitably he didn’t receive a response from me, he’d add one of the expressions he repeated often: “A man cannot drive a nail into a stone.” Then he’d quote a famous saying from the first Shia imam, Imam Ali: “Fearfulness, which is the worst of traits in a man, is indeed the best of traits in a woman.” And then, “A woman, unlike a man, should have fear. But you have no fear, my daughter, and so I have fear for you.”

“I fear for you, Habibe.”

My boss at the paper told me this as he stood up and closed the door on all of the prying eyes, people eager to know more about the woman who had barged into our office claiming that I’d had a relationship with her husband. The woman had not been wrong, but the husband she spoke of was a man I’d seen for the last time under the Seyyed Khandan Bridge over two years earlier. I’d met him that day to tell him I didn’t want to see him anymore because, among other things, he had lied to me about not being married.

I didn’t have to explain any of this to my boss, but I did. After I was finished, he said, “Be that as it may, you can’t go around trying to vindicate yourself to all the people this woman has been poisoning against you. Do you understand? People will judge you because that is what they do and because this is Iran. Don’t forget! I think it’s best if you don’t come to work for a week. Give it some time for people to forget about all this.”

I stood up. “I’m going to follow up on the report I have to turn in tomorrow and,” I paused, “I’ll be here at the office bright and early in the morning.”

My boss repeated, “I fear for you, Habibe.”

Walking back to my desk, I could feel the weight of the “judgment” my boss had spoken of. My fellow reporters buried their noses into their notes and computer monitors, but their silence hinted at unasked questions: Why are you still here? Why aren’t you crying? Where is your embarrassment?

My desk was next to Miss Ahmadi’s, our photo editor, though what she mostly did was to “improve” the kinds of pictures that officials deemed “improper.” I knew Miss Ahmadi lived alone, but despite her meager salary, she was also the sole supporter of her mother and younger sister. As I sat down I saw that she was busy using Photoshop to add a collar to Nicole Kidman’s exposed neck and shoulders. I patted her back. “In addition to your work with Photoshop, you could go into business as a tailor. Think of all the sleeves, collars, and pants you’ve created out of thin air for famous women all these years!”

She smiled and changed one pair of glasses for another. “You wouldn’t believe it, Habibe. Nowadays whenever they send photos my way, what I immediately notice are all the uncovered ankles, chests, upper arms, and shoulders that I have to ‘edit.’ I swear to God, it’s like I’ve become another one of those lecherous guys on the streets who see nothing but flesh everywhere.” She zoomed in a little closer on Nicole Kidman’s gorgeous figure to make sure she hadn’t missed a body part.

I gave her a thumbs up. “Your handiwork is perfect.”

She turned back to me. “Perfect? As what? As some horny guy fixated on women’s bodies?”

We both laughed.

It was the first time I’d laughed that day.

“But this is no laughing matter, Habibe.”

I was digging, as always, in my backpack for a cigarette. I knew my silence was getting on my friend Shahrzad’s nerves. Back from Paris for two days of Christmas vacation, Shahrzad had left Iran five years earlier. She was the third of my closest friends who had done so in the last half-decade. At first she’d left to study anthropology, then she’d stayed, which is pretty much what they all do; leave to “study” and then never return. I found a cigarette at last and asked the young waiter at the café to give us an ashtray. He looked at me a bit hesitantly and admitted, “They don’t allow ladies to smoke in the café. If the Bureau of Public Places finds out we allow it, they’ll close the place down.” I reminded him that it was true the Bureau had gotten tough for a few months, but they’d relaxed things a bit lately. He thought some more and then relented, “All right then.” He pointed to a table that was hidden away from the entrance. “Sit over there.”

Shahrzad’s shawl slipped off her head. Next to her, on a narrow column, was the café management’s notice to customers: For your own peace of mind, and ours, please control your emotions. Do not smoke (it is bad for you anyway). And please, please make sure that your Islamic head-cover is proper. Shahrzad grimaced reading the note. I laughed and lit my cigarette. She swatted at the smoke between us. “You’re laughing again? I just can’t understand why you stay in this country. Why?”

“Actually, I’m going away,” I said. Her eyes flashed at the news and she waited for me to elaborate. “I’m going to Lebanon,” I went on. “On assignment. I’m going to interview the family of Imam Musa Sadr, the original architect of the Hezbollah of Lebanon. I’ve accepted a job to write his biography. I’m going to Beirut and to the deep south. They’re taking me right up to the border where Hezbollah and Israel clash.”

Shahrzad pulled her shawl tightly back over her head. “Habibe, don’t you have any fear? You don’t, do you? But I do. I have fear for you.”

But of course I have fear. In fact, I’ve been afraid all my life. I was afraid when my brother told me that now that my studies were over I should leave Tehran and return to Mashhad. I was afraid at Tehran airport’s investigation unit—the woman who asked me where I was heading, and when I said, “Paris,” leaned in skeptically and responded, “Paris? And who, pray tell, is accompanying you to Paris for two weeks?”

I was afraid when I saw my name on the list of female reporters who could not come back to the newspaper until they corrected their “improper” hijab. I was afraid in 2009 when I watched a soldier beat demonstrators at random with his baton in 7th-Tir Square. And I was even more afraid when he suddenly turned on me and barked, “What are you gawking at?” I was afraid in Maroun al-Ras, Lebanon, when I watched several peaceful cows grazing on the other side of a barbed-wire fence and my guide told me, “That’s Israel over there. We’re at the border.” Yes, I’ve always been afraid, but I’ve always carried on. I’ve always tried to suppress my quiet frustration with compatriots who’ve made Europe, Canada, and the United States their homes, but choose to, over their vacations back in Tehran, admonish people like me for our decision to stay.

I’ve chosen the harder path. Which means: not running off to another world as soon as life gets tough. It means staying in your own country and engaging in its discourse, even if you have to be cross-examined now and then at the Armed Forces of the Islamic Republic of Iran’s Division of Topography. The harder path means reporting from here (rather than reporting about Tehran from London or Washington); it means intimately knowing Tehran’s back alleys and countless addicts, its impossible traffic, its unbearable pollution, its corruptions, its day-to-day humiliations.

When expatriate friends ask why I don’t leave Iran, I lie and tell them I don’t have the patience to speak in any language other than Persian.

For all of this, I feel I should be respected and not pitied, because what I do for a living, journalism—journalism in Iran—is of special consequence. I stay because, as my mother never stopped repeating, I am my own woman, but also my own man. Not only do I have to compete, neck and neck, with men in Iran as a single woman; not only do I have to sometimes stay until 11 p.m. at the news desk to meet a deadline; not only, on my way home on those late nights, am I followed and accosted, because a woman should not be out so late by herself; not only, when I visit, say, a real-estate office to rent an apartment, will the agent’s attitude change immediately when he finds out that I’m on my own; not only do I inevitably get a variety of offers on such occasions (mistress, temporary wife, second wife); and not only, when I politely decline, will the same fellow’s “kindly” offer suddenly turn into outright hostility; but also, on the other side of this societal split, I find myself being censured by my own milieu for bothering to stay at all, for bothering to fight it out. Because this is a fight. And if women like me don’t stay then nothing will ever change.

I don’t mention much of this to all those friends who vacation in Iran, or to those “writers” who take their Grand Tour of the country before writing their memoirs about us “poor folk” here. Because, truly, it is not their fight; it is not their issue. Instead, when expatriate friends ask why I don’t leave Iran, I lie and tell them I don’t have the patience to speak in any language other than Persian. This I heard from the lips of one of my professors a long time ago, and I decided then that it was the perfect answer. Why? Because it is an answer that’s neutral, an answer that does not force one to qualify the reply with one’s gender.