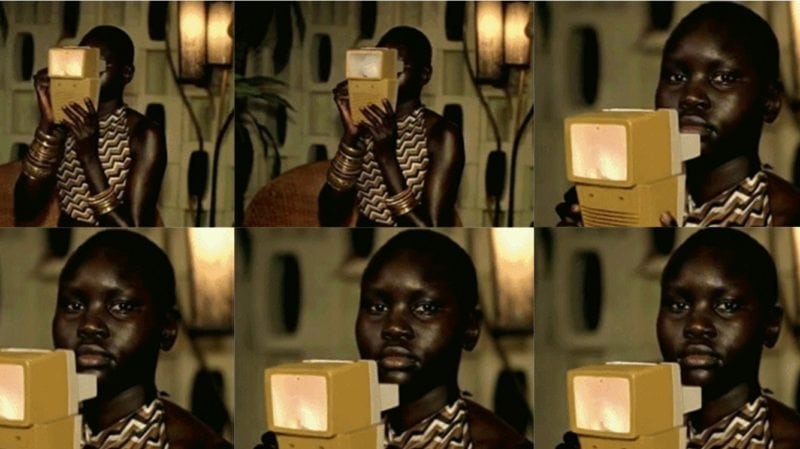

“Got ‘Til It’s Gone” opens with a pan over Black men and women in oversized collars and modest dresses. The beat drops as the camera enters a house party. A sign on the wall reads Europeans Only / Slegs Blankes, evoking apartheid South Africa. Then Janet Jackson snaps her fingers. She has gathered her hair in pigtails that defy gravity. This is her thick, curly, unapologetically red phase. As Jackson croons onstage, the dance floor comes alive with motion. It is an ode to Blackness in sepia, with the full spectrum of undertones represented, midnight blue to albino paleness. The rapper Q-Tip is Black, so is the waiter carrying drinks, so are the children holding each other in the dim light. They take each other’s portraits and bathe in the open. As if ignited by the notes, they jump and clap and stomp and slow-dance. Safe from the white gaze, the people move with abandon and tenderness. This room is made for them; it is free. As the video draws to an end, Alek Wek appears—her head bald and skin a ripe black. The yellow stereoscope she holds covers most of her face. Inside her lens, a man stands tall, chest puffed with pride. Wek lowers the stereoscope down, recasting herself from observer to observed. She smiles serenely. This was the first time I ever saw her. It was the summer of 1997 and I was nine years old.

The anomaly of Wek’s presence startled me. French culture of the nineties rarely showcased Black girls, the darkest ones most rarely of all. Despite the thousands of African immigrants who lived in my housing project, and the millions more outside of it, media titans had conferred and concluded that black faces were unrelatable to the only audience that mattered, and unrelatability didn’t sell. But we featured well as objects of pity. Yellow-eyed and joyless. Bellies distended by hunger. Flies hovering over little buzzed heads. A white man would peer into the camera with an impassioned plea: For ten francs a month, be a hero and bring clean water to this African child!

Visibility otherwise demanded a certain exceptionalism. You had to be American, like the cool kid who played Rudy Huxtable on The Cosby Show, or be an out-of-this-world athlete, like the figure skater Surya Bonaly. Girls my complexion didn’t model in clothing catalogues or grow up to present the evening news. Nor were we written into fairy tales. To play princesses, we suspended more reality than our white friends. Brooms morphed into horses and rugs into flying carpets. But our skins also became white, our noses narrow, our hair silky.

Wek was nowhere and suddenly everywhere. A modeling scout had noticed her walking around a street fair in London, five years after she emigrated from South Sudan at fourteen. By the end of 1997, Wek had walked runway shows for Chanel, Jean Paul Gaultier, Donna Karan, Ralph Lauren, Isaac Mizrahi, and Alexander McQueen. She’d also become the first African woman to grace the cover of Elle magazine. I admired the way color vibrated against her skin, the way it declined to blend and self-erase. Her ethereal hue was a worthy canvas.

I found her sudden omnipresence surreal. Here was an indigenous African woman front-and-center on newsstands. This, even though her ethnicity lacked ambiguity. This, even though there was no soft wave to her hair, no unusual tint to her eyes. Wek was blacker than me at the height of summer. Most of the time, she had no hair! Yet, authorities on the matter of beauty had designated her an icon. Until Wek, the possibility had been inconceivable to me.

Châtellerault, the French town where I spent my first six years of life, was small and majority-white. In places, it was quaint. Its heart pulsed with cobblestoned streets that wound like varicose veins between artisanal storefronts. Much of the population descended from farmers and manual laborers, and now powered the institutions that made up our modest town—boulangeries for breads, patisseries for sweet confections, and tabacs for cigarettes. My own dad pushed sand at a factory for car parts.

My then-married parents and I lived in a rent-controlled building in the Plaine d’Ozon. The neighborhood was young, erected in the sixties to accommodate an influx of migrants from the former French colonies and protectorates. Over time, it had become the most diverse part of town. And the poorest, as its early residents and then their children faced chronic underemployment and discrimination. Our neighbors were asked to assimilate—to speak less Arabic and African dialects in public spaces, lest they attract the ire of their new compatriots. They were to demand less help yet not be so presumptuous as to expect equal citizenship, and with it, paying work to feed their families. They were to submit to the superior culture without question, as when, in 1994, the Minister of Education banned what he called “ostentatious” religious symbols from public schools, though his primary target were Muslim girls who wore the head scarf. “History and the will of our people was to build a united, secular society,” the Minister had said of the ban. “The national will cannot be ignored.” Our neighbors were reminded of this while walking the underpasses spray-painted with France for the French. Welcomes had their limits. For people like them, for people like my mom, there had to be a back home. A safe harbor where no one could claim they didn’t belong.

The scope of the segregation was near impossible to measure. The French legislature had ensured it when it made the collection of ethnic demographical information punishable by a five-year prison term and €300,000 fine. But I had a sense, from being gawked at and prodded in public spaces. Outside the Plaine d’Ozon the looks I drew varied from the curious, when accompanied by my white dad, to the suspicious, as I entered stores holding my mom’s black hand.

I was in the checkout line at our local grocery with her when I saw a girl no older than me, three years old or so, glaring at me from her mother’s shopping cart. She sustained eye contact until she’d gathered the courage to ask her burning question.

Why are you black?

At a loss for an explanation, I asked: And you, why are you white?

The girl didn’t have an answer either so it ended there, with her mom pushing her cart onward, seemingly amused, her day undisturbed. But my own mother had seethed all the way back to the little apartment. How audacious, how impolite, of this child to harass strangers. I didn’t owe her an explanation for my existence. I didn’t owe her anything!

In my mom’s retellings of the face-off, and there would be many over the years, I was a brave little girl. The administrator of a knockout. I’d stood up for myself and made clear that I belonged. But this was not how I remembered it. Feet dangling from the cart, I wondered in earnest. Why was this girl white and not me? Why did she get to be normal?

When our schoolteachers asked where we were from, freckled children with last names like Dupont and Marcel were allowed to say: Châtellerault. But the rest of us were trained to hear the question within the question. Olive-skinned classmates, almost certainly born within a ten-mile radius, answered with Morocco or Algeria. I’d say that I was from Cameroon despite having left before forming any memories.

No one had instructed us to do it. Or maybe they had, all those times when the question was repeated with gusto—where were we really from?—until we kids internalized the echelons of citizenship. Our parents’ back home was ours, too. We were too small to sense the precise outlines of our otherness, but understood whiteness as the reference against which to measure ourselves. Some bodies were simply more normal than others, born to relate rather than be related with.

Yet, to me, blackness remained an alien feeling. I was four on my first vacation to Cameroon. The night my mom and I touched down, several little cousins materialized at my grandmother’s door, eager to coax me outside. Yaoundé was unfamiliar territory. I felt timid and a little afraid. This city looked nothing like Châtellerault. A coat of dust tinted its surfaces a ferrous red, from the walls of houses to the overloaded yellow taxis to the children’s scrawny legs. Coarse vegetation wrestled out of the concrete and asphalt as if to reclaim its rightful ground.

Darkness blanketed the courtyard. Having read The Jungle Book dozens of times, I worried about panthers and snakes lurking in the shadows. Still, I dragged myself outside. My newfound friends and I played for a long time, sharing old games and inventing new ones together, pausing intermittently to giggle at each other’s accents. I spoke like the cartoon characters in the French imports; and they like a magnified version of the voice my mom put on during calls to back home. Calls to here. After a while, I ran inside and announced: Maman, they’re all black!

Truth was, I felt white. My hometown was mostly white. So were my dad and grandparents. I saw their faces more than I saw my own. We thought alike. The French countryside of their childhood was the countryside of my own. I was more like them and the girl from the checkout line than my Cameroonian cousins.

Or, I felt that I was. I wanted to be. Sometimes, I thought there was nothing I wouldn’t do for the black to wash off me as it did from Michael Jackson.

At night, I bargained with God. If He let me wake up white, I’d never lie again. If He let me wake up white, I’d tidy up my room without being asked. If He let me wake up white, it’d be easier to be good. In the morning, I woke up to find my skin an obstinate brown. Dark as mud; dark as dirt.

More than anything, it was my hair that I resented. Maybe because, unlike my skin color, my hair could achieve whiteness without divine intervention. In its virgin state, my wild afro pushed outward and sprouted knots within seconds of being detangled, prompting a fresh grimace with each pass of the comb. It turned wiry in dry heat and shrunk like cheap cotton if kissed by a single droplet of water. It was voluminous and dense. Dozens of African women had stood over my head and sucked their teeth while roughing up the thickness with their fingers. I wriggled in pain in their halogen-lit kitchens while they yanked and pulled and jerked my hair, as if its nature was a personal affront. The women huffed. Mmm. Hard hair. Bad hair. And I believed them. When the day was done, the braids were so tight that it hurt to blink. Individual strands would pop off at my hairline, exposing the root’s minuscule white bulb. No use in moaning, though. Il faut souffrir pour être belle, the women liked to say. You have to suffer to be beautiful.

I felt prettiest—at my whitest—when my mane was numbed straight. On special occasions, Christmas Eve for instance, my mom would sit me down in the kitchen and place the gold comb on the gas stove before dragging it down the length of hair with a sizzling hiss. I shrugged off nicks to the scalp as a welcome cost. By the time my mom finished with me, long tresses tumbled to my shoulder blades with grace, and the faint scent of charred protein. I ran around, inventing reasons to whip my head so they’d sway like a real French girl’s.

I was five when my mom got fed up with it. That morning, she was trying to pacify the afro into two cornrows, but by the time the first braid was complete, my eyes and nose ran so profusely that my vision blurred. Before I could stop her, she stormed off to the bathroom and returned brandishing a pair of scissors. I watched in horror as she snipped off the long braid at the base of my neck. Later that afternoon, I sat in a spinning chair in front of the wide mirrors as a large barber carried out my mom’s instruction: buzz it all off.

I remember the brightness of his shop, clumps of my hair floating to the ground, and the tears choking in my throat, although by then crying wouldn’t have mattered. The girl who stared back in the mirror was an object of pity. Hideous, I thought, resenting the cut almost as much as I resented inheriting this unruly hair in the first place.

The haircut also taught me that suffering had to be withstood. I absorbed the lesson as a challenge. The next time African women wrangled my hair, I clenched my jaw the way my mom had learned from my grandmother, who herself had learned from my great-grandmother. The women in my family were mountains, impervious to the battering of seasons. And they had to be. No one—no man and no state—was coming to their rescue. All they could do was believe the strife before them could be overcome. Suffering was inevitable but they could build calluses on their own terms. To survive, the women deflected pain as if it were their superpower. I wasn’t quite a mountain, but felt I could make them proud by drawing from their towering strength and adopting it like an armor.

The source of the stories we told about ourselves could be such a blur, though. Had my grandmother and great-grandmother believed they could withstand unfathomable pain based on their own experience? Or had the myth seeped in from elsewhere? Perhaps from the white men who bought and stole members of our clans to ship across the seas, and there, to subject them to more pain than they ever would ever do their own people? And so the myth transcends family lore; it is ingrained in ways nefarious and banal, deeply rooted in institutions with material impacts on people’s lives, and in their historical foundations. As the journalist Linda Villarosa wrote:

In the 1787 manual “A Treatise on Tropical Diseases; and on The Climate of the West-Indies,” a British doctor, Benjamin Moseley, claimed that black people could bear surgical operations much more than white people … To drive home his point, he added, “I have amputated the legs of many Negroes who have held the upper part of the limb themselves.”

More than two hundred years later, a study from the University of Virginia would find that a concerning number of medical professionals still associate the concentration of melanin in some people with an innate, almost supernatural strength. Forty percent of the first-year medical students surveyed believed black skin was thicker than white skin. Thirty-nine percent of the participants who were not medical students thought Black people’s blood coagulated faster than white people’s. An earlier study found that Black subjects were themselves susceptible to believing that other Black people feel less pain than their white counterparts. I’ve wondered whether, in answering the study’s questions, these Black subjects experienced the same warped sense of pride that I saw in so many Cameroonian women, that I still saw in myself sometimes, while imagining a wall of strength in my likeness.

In the sphere of beauty, the myth demands our acceptance of pain as a necessary and even desirable aspect of transformation. Too often, the transformation arced in the direction of the whiteness we coveted while playing princesses. The myth underlay the abrasive products that we applied to our external layers to get there, as if the darkness of our features, hair we called hard and this skin the color of heat, were themselves indicators of resistibility.

Ironically, Afro-ethnic hair is the most delicate of all hair types. Its scale-like wall of cells, which shields the cortex and medulla, is typically several layers thinner than in straight hair. It’s also smaller at points of the strand where the hair curls. African descendants tend to produce less sebum, the body’s natural way of delivering moisture to the skin and hair, which makes Afro-ethnic hair prone to dryness. This combination of attributes means that, despite all assumptions to the contrary, my hair type is more sensitive to tension than straight hair. In other words, it takes less force to break it. Yet the coarser our hair—which is to say, the more fragile—the harder we yanked, pulled, jerked, and worse.

After my hair grew back, my mom thought we’d get along better if it were straightened permanently. She wasn’t wrong. I was seven or eight when she first relaxed my hair chemically. I remember how the boxes were branded with a pledge. Dark and Lovely. Soft and Beautiful. Little Black-American girls beamed in sleek ponytails. The longer the relaxer sat in my hair, the more noxious the smell became. The scalp would tingle, then burn. Pliable hair, white hair, was minutes away. I suffered gladly. The rinse-off left mine with an unparalleled limpness. Over the next eight to twelve weeks, the compact new growth would clash with the catatonic strands until it was time for the touch-up again. Most African women and girls around the world participate in this ritual at least once in their lives.

Chemical relaxers have been around for more than seventy years. The first generations, commercialized in the early 1970s, were made with lye, a corrosive alkaline liquid present in laundry products, drain cleaners, and disinfecting solutions. Over time, a milder guanidine hydroxide product, also known as no-lye, was introduced. The most common side effects are no secret among users: skin irritation, scalp lesions, hair loss, breakage, and discoloration are all par for the course.

Other potentially serious effects are less understood. But both lye and no-lye relaxers contain phthalates, which are suspected of disrupting estrogen production and other parts of the endocrine system. One study published in the American Journal of Epidemiology set out to evaluate the connection between frequent use of chemical relaxers and the incidence of uterine fibroids, benign but sometimes painful tumors that can grow on the uterus. Black women are the largest consumers of chemical relaxers; they are also much more likely than white women to suffer from uterine fibroids. That the study was the first of its kind was surprising and not. Questions particular to Black women’s health garner less attention from the scientific community. The researchers reported a positive trend between chemical relaxers and fibroids.

I’ve evaded them so far, but fibroids are such a common feature of Black womanhood that they’ve always been part of my vocabulary. My mom and aunts had them, as did my stepmom, and many of the African women who once braided my hair. Fibroids were mere inconveniences until the bloating turned excruciating, the heavy periods nailed you to bed, and the aching made vaginal sex a nonstarter. The tumors could be removed surgically but often mushroomed again, at times obstructing the viability of embryos and fetuses. One sure way to be rid of them was excising the uterus altogether.

Despite this, the Food and Drug Administration has continued to let manufacturers of chemical relaxers run their multibillion industry without requiring warning labels for even the mildest, well-documented side effects.

I am still not sure which type of relaxer caused me to develop a sustained soreness in the middle of my scalp for half a decade. But nothing about this struck me as odd at the time. We had to suffer to be beautiful.

I stopped relaxing my hair in middle school, three years after Wek appeared in Janet Jackson’s video and a few months after leaving France for Harlesden, a working-class neighborhood in northwest London. This was no coincidence. Harlesden’s demographic was incredibly diverse. In 1999, the neighborhood was near 40 percent Black—evenly split between West Indians and continental Africans—and 30 percent white, with a significant East and South Asian population.

My public, all-girl Catholic secondary school reflected the neighborhood’s makeup. Never before had I been taught by a Black woman. As for my classmates, they were self-possessed, smart, hardworking, and outspoken Black girls—deeply British, to be sure, but also attached to their parents’ heritage. The sheer quantity of blackness represented at the school shaped its culture, from what music trended and what clothes were fashionable out of our uniforms to what hairstyles were popular.

In Harlesden, blackness was a ticket of admission rather than a burden. Despite my thick French accent, and tenuous grasp of British idioms, there was a common experience on which to found new friendships underneath. When my friends took me to the London Carnival I picked up the dance moves easily, recognizing the drumbeats of Soca as distant cousins of the Bikutsi rhythms from back home. There, some white girls wanted to subject themselves to the pain of getting cornrows. The point of reference looked like me. And though my newfound comfort didn’t quite rise to assimilation, those three short years in England were indispensable in transforming my relationship to this body. For the first time, I felt proud of being black-skinned.

I’ve wondered, though, whether I’d have had less to unlearn being raised back home. As elsewhere on the African continent, it was common for little Cameroonian girls to wear their hair cropped to the scalp. This was not coded with gender or beauty. Rather, heads were routinely buzzed for convenience, to avoid lice and big tears until a girl had the maturity to get through braiding day. Among Ewondos, my mom’s clan, shearing one’s hair also bore spiritual significance. It could be a last sacrifice and tribute to a loved one.

When headmen still ruled over tribes and great families, widows used to be forced to shave their heads. Now, the custom was voluntary—a true act of sacrifice. Soon after my dramatic haircut, my recently widowed grandmother had chosen baldness for a year to honor my grandfather. How little then, and how much more, hair could mean. I envied my grandmother’s clarity. It wasn’t that she didn’t care for her looks. Far from it—my grandmother had a penchant for smart dresses, preferably cinched at the waist, which she paired with cornrows braided in bold patterns when her hair was long. She was deeply feminine and loved to feel beautiful. But a lifetime in her homeland had inoculated her from the standard that shaped my childhood. Neither the advent of chemical relaxers nor the spread of European faces on the African continent had ever caused her to measure her beauty in white terms, to question her worth.

Not that the African continent has been immune to Eurocentric standards of beauty. Proximity to whiteness continues to be revered in Cameroonian culture. Being light or appearing métissée, as having any amount of non-Black ancestry, is considered a fortune. A mark of beauty and superiority. For those of us raised in the West by Gen X and Baby Boomer mothers, whiteness often slipped into a point of reference at home, despite our mothers’ childhoods on the continent.

We heard our mothers on the phone, speculating about whether long-lost acquaintances were stricken with illness given the depth of their blackness these days. And we noticed aunties growing yellower everywhere but their joints, an improvement they credited to good health and good genes without once mentioning the pink tubes of Fashion Fair Cream on their vanities. For whatever reason, the bleaching lotions struggled to penetrate the skin at the knuckles, elbows, and knees.

Creams in this family typically lighten the skin using one or a combination of three active ingredients: mercury salts, hydroquinone, and steroids. Misuse can lead to a range of health issues, from bacterial infections to blood poisoning, damage to the neurological system and kidneys, and even comas. The market is poorly regulated, so the ingredients’ incidence varies between brands and sometimes from batch to batch. Several African nations—Ghana, the Ivory Coast, and Rwanda included—have banned their use, but the overall market remains robust.

In late 2018, the African-American model Blac Chyna partnered with the Cameroonian-Nigerian pop star Dencia to launch a bleaching line together: Whitenicious x Blac Chyna Diamond Illuminating & Lightening Cream (priced at $250 per 100 grams). Dencia once told a British interviewer that the white in Whitenicious means pure. The comment ignited an uproar but Dencia had simply admitted what each of my aunties assumed when they doused themselves in Fashion Fair, what each of us read into our mothers’ urgings to cover up our arms and legs before playing outside in the summer.

Instructions on the Fashion Fair tubes recommended applying the cream on areas marked with permanent discoloration, skin made darker by scarring and sunspots. But what if you were praying to be pure all over?

Even in the midst of the resurging natural hair movement, when odes to body positivity and Black self-love are one click away, the power of white supremacy persists in beauty standards. Embracing my own skin was a process, a state arrived at. Getting there had taken seeing it in other Black girls, over and over. Years later, my position still feels fragile. Like a person recovering from an eating disorder, I must monitor my relationship to the things that activate my insecurities, stop myself from resenting my skin and hair, from coveting lightness. It’s harder when the trigger is in the body.

Nor do I have the luxury of opting out of this preoccupation altogether: Racial implicit bias is a core feature of American life. What certain people feel about Black women’s hair, its texture and what we do with it, bears material effects. It’s the difference between getting a job offer and getting passed over, getting an apartment and getting denied. Until everyone’s outer layer is equal, and whiteness is no longer the point of reference, I must balance the degree of attention I pay to my appearance with the self-awareness to occasionally pause and ask myself: What feelings am I trying to elicit in other people by wearing my hair in styles coded as white? And is it worth it? An exhausting exercise, but I’ve been conditioned to suffer worse.

January 2013 marked five months in my first career job as a government lawyer in DC. Things were going well. My assignments were engaging and my supervisors generous. I was working hard because I wanted to be perceived as sharp and industrious, but also because being the only Black hire in the entering class of junior lawyers made me doubt whether I deserved my job and whether my colleagues agreed. The fear of being a token fed my imposter syndrome. If I was found to be excellent, I wanted it to be on merit, rather than an impression of the kind of Black person my supervisors thought I was—the kind of person I’d led them to think I was.

Before my in-person interview and first day of work, I’d taken out my nose ring and worn my hair in a straight bob. To project conventionality, I think, and make my bosses feel at ease around me. I wanted to be relatable. Months later, I was still running my hair through a searing flat-iron. The intense heat thinned my hair and broke it on the ends. Nevertheless, I continued until the tresses drooped to my neck and swayed when I turned. But the more time I spent in this routine, the more I felt the little girl who whipped her hair like a real French girl come creeping back. She who would do anything to be white.

One Friday morning that January, I packed a knitted hat for the cold and left for the day. After work, I took the metro to a hair salon in northwest DC, and spun in my hairdresser’s chair. Nicole was finishing another head. I waited for her in front of the wide mirror, remembering my mom’s voice at the barber shop. That day, my body had been a shell I didn’t like and had no control over. A little thing futilely reaching for whiteness.

Nicole passed her hands across my scalp. I liked going to her because she never treated hair as insurmountable. In her shop, hair was simply protein; a blank canvas for play. There was no hard hair or bad hair. Only people without the know-how to appreciate its vulnerability and care for it accordingly.

So, what are we doing? Nicole asked.

I looked at my head one last time and said, Buzz it all off.

My friend Dvora and I were sitting at an outdoor restaurant table in Brooklyn one summer evening in 2017, when I noticed the woman a few feet away. She was slender and tall, with impenetrable black skin. Her hair was cropped as short as mine had been at its shortest. I watched her glide into the restaurant with two men trailing her. Dvora slipped a crumb to her beagle mix, Lizzie, and carried on chatting. I couldn’t put my finger on why, but the sight of this stranger awakened an unexpected melancholy, as if she were an apparition from a sadder time in my life.

I excused myself from the table, under the pretense of getting us wine. The woman engaged in a lively conversation at the small bar inside. She reminded me of Alek Wek, but the math didn’t add up. If Wek was already successful when I was in fourth grade, then she was nearly forty. This woman was my age. A doppelgänger or possibly a relative.

Loose threads of a stale news story flashed back to me. Something about another fashion model’s mysterious disappearance from New York, a couple of years back. As the story gained traction, the missing model’s face had circulated around social media. I’d been struck by her resemblance to Wek. (Ataui Deng was in fact Wek’s niece and had been found safe in a hospital.)

I waited for the bartender’s attention, pondering whether to interrupt the woman’s conversation and ask if she was related to the famous beauty whom I once admired. I guessed she’d received this comparison a thousand times. At the first lull in their conversation, I approached and said, Hi, are you Alek Wek’s niece?

The woman smiled but shook her head. I felt like an idiot. I debated whether it was worthwhile to explain, without boring her friends, who Wek was, and how her streak through the fashion world had changed my narrow conceptions of beauty. How Wek had made me feel seen. Flummoxed with embarrassment, I apologized to the woman for the strange question.

It’s just that you look so similar.

I’m not her niece, she said. But I am Alek.

Standing before Wek, I felt shy and awed and sad and indebted to her at once. Moved in a way that I struggled to articulate. I told her how important her work had been to me as a kid, that it’d meant a lot to see someone who looked like her in magazines.

Back at our table outside, I tried to put what had just happened into words. I thought I’d reached my limit for surprises when Dvora said, Oh, Alek is in there?

My eyes opened wide before I could conceal my astonishment. Dvora was a sportswriter raised in Orthodox Judaism. Of all the models who could have left their mark on her in the nineties, Wek wouldn’t have been my guess. Then again, I was living across the Atlantic at the peak of her career. What did I know?

Dvora chuckled. Our dogs are friendly!

Wek waved us goodbye on her way out and I waved back casually, despite the boundless gush I felt inside. Hours later, I was curled up in my Amtrak train back to DC, still reeling, when my phone vibrated. It was Dvora.

FYI Alek Wek is texting me about you.

Was I weird?

No, Dvora wrote, and then nothing.

I thought of the little girl who’d first encountered Wek on a grainy television, who didn’t yet understand that power—economic, political, or cultural, or a combination thereof— was a function of control. I knew better now. It wasn’t enough to be present and observed, to be represented. Power required holding the levers that produced capital, steered institutions, controlled the creation of art. But representation was not meaningless either. As French media erased little Black girls from the public eye and African women erased their own pigmentation all around me, seeing my blackness elevated had mattered to me.

A million-years-long minute passed while Dvora worked on copying and pasting Alek’s message. Finally:

She is what makes me not give up creating meaningful images in fashion.

And I, too, felt grateful to Wek for not giving up.