The following is excerpted from The Playwright at Work: Conversations. Published here courtesy of the authors and Northwestern University Press.

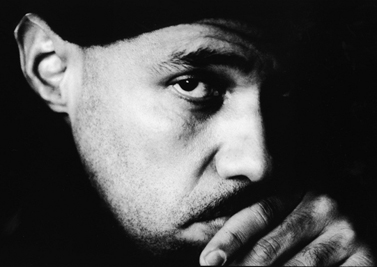

It was raining hard the morning we interviewed Nilo Cruz. He arrived at Barry’s apartment wearing a leather jacket, carrying a tiny umbrella and a small paper bag, the contents of which he kept secret, and a hat which he kept on during the interview. Nilo lives in Miami, and we happened to catch him on one of the few days he was in New York to attend a New Dramatists luncheon. He’s tanned and handsome, with a small mustache and goatee. During the interview he often addressed each of us directly, reaching across the table to make a point. His body, as much as his words, conveyed the passion he feels for his work.

–Rosemarie Tichler and Barry Jay Kaplan for Guernica

Guernica: In preparation, as we do with all the playwrights, we reacquaint ourselves with your work. We feel like we’re rediscovering them.

Nilo Cruz: Thank you… Everything seems to be Anna in the Tropics and that’s it. It’s like I never wrote anything before that or after that.

Guernica: We think your plays are very different from those of any other writer whom we talked to. Your plays just seem romantic in the best way. The language was lyrical without being “poetic.” Is that a Latin sense, or is that you, Nilo Cruz?

Nilo Cruz: I think it’s both. I think it’s a Latin sensibility. But I’m also very much inspired by the music that comes from my country, especially the romantic boleros. Not that when I sit to write a play I listen to boleros. But I think it’s part of my DNA, it’s part of my upbringing. I grew up in a house where this is the kind of music my parents used to listen to. This is the kind of music I would even hear in my neighborhood. I think that sort of romanticism is part of the culture.

Guernica: Is it the music of the middle class? Is it high music? Is it popular music?

Nilo Cruz: I think that it is the music of the people. It is the equivalent of fados in Portugal—the equivalent would be ballads in this country. So in Cuba we have boleros, which are songs of the heart. I’m interested in—for lack of a better word—in love and expressing that through my plays. I love love stories. I think it’s important to see a good love story.

Guernica: But they’re very hard to write without being sentimental or wrapping things up in some kind of neat way that makes people go, “Aww.” Whereas A Bicycle Country is very romantic and it’s even joyful, but it’s not happy.

Nilo Cruz: No, it’s not happy.

Guernica: And others. The Color of Desire.

Nilo Cruz: That’s brand new. I’m still even exploring that. It’s interesting because I’m doing a translation of The Color of Desire right now into the Spanish language. What’s so curious about doing the translation is that it’s allowing me to enter the play again and to even edit the play a little bit. So when I’m looking at the scenes and looking at the dialogue, thinking, “Is this really what this character is saying at the moment? Do I need this line?” I’ve been able to edit a few things from the play through the process of translation.

Guernica: Did you always write directly in English when you wrote? How did that start?

Nilo Cruz: It’s a curious thing with me. I do write in English because I did educate myself in this country, even though I was ten years old when I came here.

Guernica: Did you know any English?

Nilo Cruz: I did not, no. I don’t know if you’ve noticed, but I still have an accent. It’s not major, it’s not very pronounced, but I do have…

Guernica: You came here at ten. So in Cuba, your influences were the bolero, the music? Did you go to plays?

Nilo Cruz: I did go see a couple plays when I was in Cuba. But more than anything it was cabaret. Even at that age, what happens is that there’s an age difference between—I’m the youngest in my family. My two sisters were teenagers when I was nine, eight years old. So they were going out with their boyfriends. And the family sometimes would go to a retreat, a beach retreat, resort. And cabaret is very big in Cuba, as we all know, from the fifties. So one of my first experiences with the performing arts was through cabaret. All the family had gone to this resort; no one wanted to stay home with me, including my grandmother.

…[I]n terms of the performing arts, the first thing that I saw was, you know, burlesque comedic sketches. Plus a lot of flesh, but no stripping and really wonderful, electrifying Cuban music.

So basically, my father knew the owner of the restaurant, and he says, “You know what, we’ll take him tonight. He’s eight, he’s nine, he can see one of these shows.” They snuck me in through the kitchen, and, basically, I came into the restaurant, they put me underneath the table. Then when the show started, you know, I kind of lifted the tablecloth and started to see this show. By that time, the waiter had seen me and said, “Oh, he can stay.” So basically, in terms of the performing arts, the first thing that I saw was, you know, burlesque comedic sketches. Plus a lot of flesh, but no stripping and really wonderful, electrifying Cuban music. It really made an impression on me. The show also has sketches and comedians. Then, of course, there were some boleros that were being sung. That was my introduction to the performing arts. Of course, when I came home after seeing this—experiencing this—I wanted to re-create what I had seen on the stage with all my friends in the neighborhood. So that was sort of my way into the world of theater. And also my sister was dating a musician, so I was a chaperone in the family, and I used to sort of go out with her… I grew up in a world of music.

Guernica: What is it about Cuban music that is so from the heart? I haven’t been to Cuba, but I’ve been to Mexico, and Mexican music doesn’t seem like that. It seems a little harder, a little more dramatic.

Nilo Cruz: It’s probably because it’s a mixture of the Spanish with the African, especially because a large immigration that came to Cuba was from the south of Spain where you have flamenco. Flamenco is music of the heart. It’s influenced by northern Africa, all this lament. So basically, you mix that with the drumming of the Africans that came to Cuba, and you have Cuban music.

Guernica: So how did you get here?

Nilo Cruz: The States or New York?

Guernica: Let’s say the States first.

Nilo Cruz: Well, my father had tried to leave the country in the early sixties. We were pro-Castro at the beginning, when Castro came into power. Then my family got disenchanted with the regime, and my father tried leaving the country. He got caught leaving the country illegally, and he was imprisoned for two years. So basically I didn’t get to know my father for the first two years of my life. When he was out of prison, he was sort of a marked man. They knew that he was against the system. My family made the decision that they still wanted to leave the country. It took us eight years to leave the country. It wasn’t just because my father was disenchanted with the regime—my father was also afraid that I would turn military age and then maybe be transferred to another country like Russia or Czechoslovakia, because that was what was happening. My family was trying as much as they could to leave the country, whether it was through Spain—and we had relatives in Spain, we also had relatives in the United States. You need to have somebody to claim you to come to this country or to Spain. But we came to Miami legally—on an airplane, not on a raft.

Guernica: Did you become a little American boy?

Nilo Cruz: Did I become a little American boy? Well, the phenomenon is that Miami, by that time, there were a lot of Cubans in exile. So when I went to elementary school, of course, I first started with the ESL classes full of Hispanic kids. But even as a child, I realized I had to get out of ESL. I really wanted to integrate, I wanted to be American. I wanted to be with the American kids because—I don’t know—it seemed the right thing to do. When I was in school, I made sure that every time I needed to use the restroom that I told my teacher, “I need to go to the restroom,” in English instead of Spanish. So she knew, “Oh, this kid is learning, so we better transfer him to another class.” I knew that when I was transferred to another class, then I would pick up the language in a better way, much faster than being with Hispanic kids.

Guernica: When did you start to think of yourself as a writer? Or when did you start to write things?

Nilo Cruz: I did start, even at that early age, even at ten years old, I did start writing poems. I wanted to be close to books at that early age. As a matter of fact, I volunteered to work at the library to be close to books, to discover authors. I thought that would be the way to do it, shelving books.

Guernica: Were there books in your home? Were your parents readers?

Nilo Cruz: In Cuba, yes. But in the United States—you remember, you leave the country with nothing. You can’t take anything with you. By the time my parents came to the United States, they were living the life of an exile, which is all about work and trying to make a living.

Guernica: Did they speak English?

Nilo Cruz: No, they did not. And they actually never learned to speak English. Just basic language. Because they stayed living in Little Havana. My father worked at a shoe store, and my mother worked at a purse factory. So basically the employees of the factory spoke Spanish, and if you needed to speak to someone that was non-Spanish speaking, you would have somebody to translate for you. And you imagine, you spend hours working, it’s hard to go home and pick up a book.

Guernica: Do your parents figure in your plays?

Nilo Cruz: Ah, yes. There’s a play of mine called A Park in Our House, in which there are aspects of my family in that play, especially my mother.

Guernica: So you started to write poems, you were ten. When you first came here.

Nilo Cruz: Mm-hmm.

Guernica: Did that move into any other form?

Nilo Cruz: Ah… I was intrigued by theater. I remember when I was in junior high school, I remember reading Shakespeare and loving Shakespeare. I think it was the first time I made a connection with my classes. Taking math classes, what do I need math for? But when we started reading Shakespeare, there was something about that language, which just did something for me. Even before that, I had discovered a poem by Emily Dickinson at the library at the school. I was completely taken by her work, especially this poem.

Guernica: Which poem was that?

Nilo Cruz: Oh, I do not remember. It was a borrowed book from the library, and I don’t remember what it was… You know prior to that, we have a wonderful poet and a politician in Cuba in the 1800s, who was an emissary, who lived actually here in New York, but he translated Emerson and Walt Whitman. So he really was an emissary for North American literature… José Martí. We in Cuba, of course, growing up in school, we knew some of his children’s stories, some of his poems. So he was one that was also inspirational as a kid.

Guernica: Did you think of it as something that you could do?

Nilo Cruz: Not until much later, when I discovered the Emily Dickinson poem. That’s what I said: “Ah, this is what I want to do. I want to write. I want to write like this.”

Guernica: How old were you?

Nilo Cruz: I think I was in elementary school. I must have been eleven years old.

Guernica: So how did you…

Nilo Cruz: How did I make my way to the theater?

Guernica: Yes, that’s the question.

Nilo Cruz: Well, I did take some theater classes when I was in high school. But I wasn’t serious about it. It wasn’t until much later when I was, say, in my early twenties, and I was working in a hospital. I sort of had this epiphany to go to the theater. I said, “I must go to the theater this evening.” I didn’t know what I was going to see.

He’s written about Dalí, he’s written about Buñuel, but he said, “But Lorca. There’s something about him. I couldn’t let go of him.” I said, “That’s happening to me!”

Guernica: Were you in Miami?

Nilo Cruz: I was in Miami. During that time, we had the Coconut Grove Playhouse, which no longer exists, unfortunately. I thought, “I’m just going to go to the theater, I’m going to buy myself a ticket and I’m going to go see a play.” I did go see a play. I saw The Dresser that evening, and I loved the production, I loved the piece. I was so inspired by that piece that I said, “I must start taking theater classes.” I didn’t know in what capacity I was going to be part of the theater, whether I was going to be an actor, a writer, or a director. But I knew I wanted to take theater classes. And, of course, when I started the classes with this teacher, which is really interesting because she was teaching a noncredited class because she really wanted students in her classroom that were committed to the art form, not someone who just wanted the credit. I started taking classes with her. This was at Miami Dade College. In class, instead of bringing in a scene from Lorca or Chekhov, I would write my own scenes, and I would direct them. I would use the students in class, and then that’s when the professor said, “You’re a writer. You need to continue writing.”

Guernica: Was it a revelation when she said that?

Nilo Cruz: It was. Actually, she said that not only was I a writer, but that I should be a director. She gave me the opportunity to direct, and I directed a play by Reinaldo Arenas, the Cuban writer. Before Night Falls. It was actually the world premiere of his piece in Miami. It went really well, it was very much liked by the community.

Guernica: In Spanish?

Nilo Cruz: In Spanish, yeah. Because her theater class was in Spanish. I started really doing Hispanic theater in Miami. This professor of mine really wanted to honor the Spanish language and honor Spanish.

Guernica: So was that a choice of yours to go from The Dresser to take theater classes in Spanish?

Nilo Cruz: Well, I knew of her. I knew she was an excellent teacher through a friend of mine who was an actor taking her class. I actually had visited her class once before, but I thought it was a very difficult class, and I wasn’t prepared for it. But now I felt it was the right time for me to be part of her class. So we did theater in Spanish.

Guernica: If you knew of a teacher who ran a theater class in English, would that have interested you, or did the Spanish?

I’ve been a little disappointed in directors in this country.

Nilo Cruz: It was the teacher. There was something about her. She was magical… Teresa María Rojas. She was magical. But by that time, I was infected by theater. I wanted to be part of the theater world. I started taking credited classes with another professor of mine who was very good too, Patricia Gross, at the same school. She started to form a theater company called South and Alternative Theater. She brought María Irene Fornés to do a workshop in Miami. By that time, this professor of mine, Patricia, asked me to direct a play for her company. I directed my teacher in Mud. It had really good reviews. She invited María Irene to come see the production and to do a workshop.

I took a workshop with Irene, and Irene liked very much what I had written in class, and at that time she was running INTAR Lab on Fifty-Second. She asked me if I wanted to be part of her lab. But I had to make my decision right away because the lab was starting on Monday, and I had met Irene on Friday. And I had to move to New York immediately. I didn’t even have money to move to New York. Thank God I had a friend in New York. I called her up and asked her if I could crash in her living room, and she said yes. I got some money, I had a little bit of money, I think I probably asked my parents for some money, and I came to New York, and I started to study with María Irene Fornés. I was twenty-eight by that time.

Guernica: Did she ask that you start writing in English?

Nilo Cruz: No, but everybody was writing in English in her classroom. To be honest with you, before I came to New York, I had also really wanted to move into North American theater. I really felt it was important.

Guernica: For the same reason that you made your teacher aware that you spoke English?

Nilo Cruz: Absolutely. I knew that if I just stayed doing Hispanic theater in Miami that I would be limited to just one particular kind of audience. I just wanted to do—I was interested in North American theater too. María Irene Fornés was very important to me because María Irene Fornés is Cuban. She came to this country in the forties or something, late forties or fifties. And I thought, “If there is this woman who is Cuban and is writing in English and is well known, especially here in New York, off-Broadway, I can possibly do this too.” So she was an inspiration. But her language, what she was doing with style and everything, was really inspirational for me. So when she gave me the opportunity, gosh, immediately, I said, “I have to do this.” I basically quit everything and came to New York to study with her.

Guernica: Did you make any money?

Nilo Cruz: Let me tell you, yes. The experience of having worked at a hospital was very helpful, because when I moved here, I worked for someone. I was like a nurse for a woman who was quadriplegic. So I was sort of like a physical therapist, nurse. And so I helped her in the house, I helped her. But INTAR had funds from the Lila Wallace Foundation, so we got paid to also write. So I got a little bit of money from INTAR and a little bit of money working for this lady. That’s basically how I survived the city.

Guernica: So now you’re in New York, you’re writing in English, now you’re with all the other playwrights.

Nilo Cruz: All the playwrights that really want to write about Latino characters, but in the English language. All the other people around me, Caridad Svich, Migdalia Cruz. Many of us. It was incredible.

Guernica: How long was this?

Nilo Cruz: Three years.

Guernica: Did you get any plays done during that time?

Nilo Cruz: No, I did not. I wrote a play called Not Yet Forgotten. I don’t even know where it is, I don’t even know if it exists anymore. Then I wrote a play called Graffiti, and then I wrote another piece, which was not even about Latinos. It took place in Italy. I was really inspired by Italy. I had gone to Italy before coming to New York.

Then when I was studying with Irene, Paula Vogel asked Irene if she had any participants in the lab who wanted to go back to school. I told Irene that I did want to go back to school, that I wanted to continue to take writing classes, that I wanted to take more directing classes, etc. So Irene suggested for me to apply to Brown University, to meet with Paula. I met with Paula and I got accepted to Brown.

Guernica: Did you do a full-year thing at Brown?

Nilo Cruz: Two years. I only concentrated on playwriting. I took other classes, theater history classes, that sort of thing, but it was a lot. Being in the workshop as a graduate student was a lot of work.

Guernica: When you write, do you just feel informed by the history of your people? Does that always fill your mind?

Nilo Cruz: Yes, in many ways…

Guernica: Do you start from there?

Nilo Cruz: I do go back there quite often, whether it’s my childhood in Cuba or whether it’s my upbringing in Miami. But I’m also inspired by other things. For instance, I wrote a play called Night Train to Bolina, which takes place in Central America. I was heavily inspired by an autobiography that I had read of Rigoberta Menchú, who is from Guatemala, and she won the Nobel Prize for peace. I was very inspired by her life. I didn’t write a piece about her life but wrote about the struggles of children in Latin America and the guerilla warfare of the eighties. It’s not set in any specific country, just somewhere in Latin America. So, yes, I draw from my life, but I’m also inspired by things that come my way.

I have stopped reading reviews, to be honest with you. Because I find writing is all about courage.

Guernica: So Lorca…

Nilo Cruz: Is definitely an inspiration because I discovered Lorca when I was studying with Teresa María Rojas in Miami. I was inspired by Lorca’s work. I actually did a couple of exercises that had to do with Lorca’s work…

Guernica: Well, it seemed very daring, really, to bring him onstage as a character and have him speak and have this famous poet speak in Beauty of the Father.

Nilo Cruz: It was brave… I was very inspired. I did a translation with Karin Coonrod that was commissioned by the Public Theater. We did a translation of Lorca’s The House of Bernarda Alba. Of course, I really started to immerse myself, not just in Bernarda Alba, but in his other plays and also his life. When I started to do research about his death and how he was killed, I thought, “I have to write about this.” And also because a friend of mine, a Spanish friend of mine who lived in Miami and was a student at the school with Teresa María Rojas, said to me that when she was in Spain, they didn’t teach Lorca. During Franco’s regime. I thought to myself, “Oh, Lord. I have to write…” Mind you, by that time, Franco was out of power. But still, I felt like I had to write about it. That’s when I decided to write Lorca in a Green Dress. Then I went to Spain. You know, I went to Spain to write Lorca in a Green Dress through a Lippman Award, which you get through New Dramatists. So I went to Spain and stayed with my friend María. You know what’s interesting when I went to Spain, I had started to write Lorca in a Green Dress. Then out of the blue, my Spanish friend I was telling you about, who told me Lorca was not taught in school, out of the blue, I hadn’t spoken to her in years, she calls me up and says, “I’m not living in San Sebastian, northern Spain, I’m living in Grenada, in the south. Why don’t you come to visit me?” I said, “I just got money to go to Spain, I would love to go visit you!” And there I finished writing Lorca in a Green Dress and got inspired. I wasn’t finished with Lorca yet, and it was really curious, because I got in touch with this biographer Ed Gibson, and he said, “Wasn’t writing about Lorca, wasn’t he like a magnet?” He’s written about Dalí, he’s written about Buñuel, but he said, “But Lorca. There’s something about him. I couldn’t let go of him.” I said, “That’s happening to me!”

Guernica: So you have your inspiration, you have something in mind, and you go to your desk. What happens there? Do you have a schedule?

Nilo Cruz: I write every day. I try to write in the morning. And usually, I don’t write an outline of my plays. I never understood outlines, to be honest with you. I don’t understand writing it down, you don’t even know what you’re going to write about. It doesn’t make any sense to me. But I start with characters, more than anything. For instance, when I was writing the piece Night Train to Bolina, I was interested in the children. I started to write, just try to imagine children in Latin America, and thought of my own life too, as a child. That’s how I started to create the characters.

Guernica: You hear them? Are they speaking in English or Spanish?

Nilo Cruz: No. It’s a really fast translation. They feel in Spanish, they think in Spanish, but they speak in English.

Guernica: That’s connected in you.

Nilo Cruz: It’s connected in me. Because I live in two cultures. I came very young to this country, but when I speak, I speak very much like a Cuban person, but I was educated in this country more than anything.

Guernica: So you start with scattered characters, and how does it become a play?

Nilo Cruz: Well, I write a series of scenes. Then I look at all the scenes, and then I start sculpting the play. To me, writing is like sketching. You don’t enter the canvas immediately—you do a series of sketches. Picasso did hundreds of sketches before he started Guernica. So I do the same thing, just to find out about my characters. Some of those scenes make it to the play, some of them don’t. So it is a process of search, doing a little bit of research about their lives through actually writing scenes and finding out about them. Again, some of them make it to the play and some of them don’t.

Guernica: Is there a moment when you go, “Ah, now I see where this is going”?

Nilo Cruz: Yes, absolutely. Through the process.

Guernica: Do you see the end?

Nilo Cruz: Not until much later. Sometimes the end has come early, and I have an idea what the end is. But I also try to trick myself not to go there until I arrive at that moment.

Guernica: So you never have an end and think, “How do I get there?”

Nilo Cruz: No.

Guernica: So it’s very organic?

Nilo Cruz: It’s very organic. It’s really the long way. It’s almost like Red Riding Hood.

Guernica: You write until you have a draft, then what do you do? Leave it for a while? Have somebody else read it?

Nilo Cruz: I don’t have people read my work. I have actors read my work. Because I need to listen to it before I get feedback from other people. Certainly, I get feedback from producers at the theater.

Guernica: But before you bring it to a theater…

Nilo Cruz: No, I don’t. There’s a lot of writers that do that, but I’ve never done that. I don’t show my work to another writer or someone whom I respect…

Guernica: So the first time you hear it, it’s actors.

Nilo Cruz: For instance, when I was in graduate school, it was with playwrights who’d read it out loud and I would hear it. Of course, you would get feedback immediately. But when I’m on my own as a writer, I just come up with a draft. Then I bring a couple of writers, whether it’s New Dramatists or at a theater, The Public Theater, and I do a reading to hear it. Of course, I get feedback from producers, that sort of thing.

Guernica: So what might you hear when they read it to you? What are you listening for?

Nilo Cruz: Well, I’m listening to the rhythms of the piece more than anything. How the dialogue is operating. If the rhythm is dynamic. Or if the scenes have the same tempo, and then I need to do something about that. First of all of the rhythms, then, of course, I’m listening to storyline. I think that’s what I do. It’s one thing when I sit around the table with a group of actors, it’s something else when I hear the actual reading, which I think is good because then I have a little more separation, and then I can sort of see… Because when you’re around the table, you’re almost like in the play. But when you have a little more space, and it’s actually being presented, you have a little more space, you can see, you can be a little more objective.

Guernica: What kind of notes do you get from these readings?

Nilo Cruz: I have gotten feedback from producers and dramaturgs about my play. I take into consideration the notes, some of them, what I feel works, other things I just put them aside.

Guernica: You feel secure with that? You don’t feel vulnerable? Because some writers have a hard time with it, and they just kind of try to please everybody. Do you feel, “Oh, that’s not right, but this is”?

Nilo Cruz: Absolutely. Also, for instance, with a piece like Lorca in a Green Dress, it’s a very complex play because it’s sort of surreal. If you think of dramaturgy in North America, which is so realistic and so literal sometimes, sometimes what theaters—especially dramaturgs—ask for is more information, which sometimes can really weigh down a play. There’s only so much information a play can have. If you start putting in so much information, it becomes something completely different, it doesn’t sing. So then, yes, you get information for an audience that maybe doesn’t know about the circumstances about someone like Lorca, but the play does. So, yes, you’re serving this person, but at the same time, you’re not serving the art form. I feel like as a writer, you have to take commentaries with a grain of salt.

Guernica: Do you find it difficult to find people who can enter your play and talk about it?

Nilo Cruz: I have a really, really difficult time with dramaturgy sometimes in this country, because I write about other cultures. I write about a culture that is very difficult, it is very foreign to a North American. A lot of people don’t know about what’s happening. I don’t mean to underestimate an American audience, nor American producers or people in the theater. But usually my plays take place in other countries, like in Spain or in Latin America, some of them here too. But, for instance, Anna in the Tropics, nobody knew about Tampa, Florida, and the cigar industry there. So I had to have a certain amount of exposition in the play, but I couldn’t overwhelm the piece. As it is, the play has a lot of exposition. You know, even sometimes, I have to make choices as an artist, as a writer. I think maybe my plays could’ve been a little more experimental if I wasn’t writing about other cultures. But as it is, it’s unfamiliar territory. Imagine if I made it more experimental. It would be completely unfamiliar territory. So I had to make choices sometimes. Yes, I can be experimental with form, but not too much. It’s already unfamiliar material.

Guernica: In the early days, you brought your plays to the Public. Where else?

Nilo Cruz: Well, you know where I really started—I started with the Magic Theater in San Francisco. I started through the Bay Area Festival. That’s where my plays were first read and then got picked up by the Magic Theater. Then Morgan Jenness came to the Bay Area Festival at the Magic Theater, saw my work, then came to The Public Theater and told George and Rosemarie about me. And that’s why I came to New York.

Guernica: Now who do you show your work to? Or do you work on commission? Or both?

Nilo Cruz: Listen, I was very lucky. When I got out of graduate school, I went to the Bay Area Festival. It was very helpful, when you spend two or three days with a group of actors and a director and you can really explore the material and see how the play is operating. You can go back and do a little bit of rewriting: “This is not working, well, here, let me do a little bit of rewriting before the rehearsal tomorrow.” So that was very helpful for me. I really do like working with actors and a director. Or sometimes I direct the play with actors, just to hear it, just to see how the play is operating. That’s helpful for me to then go into the second phase.

Guernica: So Bay Area was very helpful for you, to work without the big stakes of a New York opening. Can you still do that? Has that changed?

Nilo Cruz: Yes, I still do that. It’s very helpful for me. You know, it’s nerve-wracking because you feel extremely vulnerable. It’s a new piece, you don’t even know how it really operates on the stage. So then I go to readings of my play, especially when I invite an audience, which is very helpful too because you can feel the presence of the audience in the room and whether the audience really has made a connection with the play, which is very helpful for me also as a writer.

Guernica: Do you do that more in Miami now?

Nilo Cruz: No, I haven’t found a place in Miami that does that kind of work. Unfortunately, Miami is lacking in terms of script development. Not a bad thing, not a good thing because I find that the rest of America is over-developing plays.

Guernica: You still come here to New York?

We’re not allowed to direct our own plays in this country, and I think it’s really unfortunate.

Nilo Cruz: I come here. And I’m lucky. For instance, with The Color of Desire, I did a reading at the Manhattan Theatre Club, I did a reading of The Public Theater, I did a reading at O’Neill. That play has taken me a couple years to write, fifteen drafts. Every time I do a reading, every time I do a presentation, I learn more and more about the piece.

Guernica: So is it that you learn, “Oh, that doesn’t work, take out that line because the rhythm is wrong,” or is it that you see an opening into something that needs to come out more?

Nilo Cruz: That too. I realize that I perhaps need to write another scene or I perhaps need to expand a little bit more a section of the piece.

Guernica: Or do you go into it, hoping this is it?

Nilo Cruz: You’re always hoping this is it, and you don’t have to do any more work. I’m always hoping, but that’s not the case.

Guernica: So in rehearsal when you’re not directing, what kind of director do you like working with?

Nilo Cruz: I’ve been a little disappointed in directors in this country. I mean, there are great directors here. But I don’t really like—I’m really after a theater that doesn’t just deal with the actual texts that I brought in. But really with a director that really deals with images too, that takes the play to another level. Because a play can only do so much through dialogue. We have to remember that theater takes place in the third dimension, and we have to take into consideration the visual aspect of the play. I found a few directors here and there, but I really want a director that just goes between the words and really brings also an image. Because I really think images are important for the theater. Because I do write images.

Guernica: Have you found a difference in London?

Nilo Cruz: In some ways.

Guernica: Because the designer seems more important in London. They get second billing…

Nilo Cruz: In some ways. You know, I just did a play in Paris, and I worked with a director who was very visual. Very pared down, but very visual… I think it’s a combination of creating an atmosphere—because my plays are very atmospheric—but you really have to create images. For instance, right now, I’m about to direct one of my plays, Night Train to Bolina, and I’m thinking, it’s a very particular play because the beginning of the piece, it only starts with two characters, then I add other characters. And I thought, “Wow, if I were to direct this play, what if I start this piece with some of these other characters and try to create a visual narrative for them, even though there is no written language?” The audience might be wondering, “Who are these people? They haven’t even spoken yet, but I see them.” And try to create a narrative, a past history only visually. In between the scenes. Or at the beginning of the play too.

Guernica: Would you feel free to let a director do that, even though you hadn’t necessarily been thinking that way?

Nilo Cruz: That’s a really good commentary, Rosemarie, because I tell you, I think at the beginning, when I just finish a play, I’m still so caught up with being a playwright, wearing the playwright’s cap, and with the specific world, that these ideas don’t come to mind yet. We’re not allowed to direct our own plays in this country, and I think it’s really unfortunate.

Guernica: I think maybe you should direct your own plays because they come from a different culture than most directors in America are familiar with. And you were brought up directing. But you also know the dangers of directing your own work.

Nilo Cruz: Absolutely. And I agree. And there’s dangers to that too. I realize there’s dangers. But listen, every director is always directing around the play. If you have an actor who really doesn’t get the character well enough, you have to direct the play around that character. You have to make choices with that actor. If you have an actor that really doesn’t get the role and has certain visions of the role, sometimes you have to direct around that actor. I was directing Anna in the Tropics in Spain, and I’m the writer, and I was the director of the piece, and I was working with a very important actress, and we didn’t meet eye to eye on a particular role. And she said, “No, I don’t see it that way.”

Guernica: And what did you say?

Nilo Cruz: I had to respect it.

Guernica: Was there no way you could…

Nilo Cruz: I tried to direct her a certain way, where she would meet me halfway, and she did meet me halfway, but…

Guernica: Was she right at all?

Nilo Cruz: It was an interpretation of the piece.

Guernica: That you didn’t agree with?

Nilo Cruz: I didn’t disagree with it. It’s one way of looking at the role. I might be contradicting myself, but not really. Because theater is about interpretation and what an actor and what a director brings to a piece too. So this was one interpretation of the role, you know. It was not my ideal role, but you’ve gotta be open to that. I’m open to it every time I work with a director and a group of actors. I have to be open to that interpretation. I’m not one of those hysterical playwrights that come and say, “This is not what I intended to do.” It’s one rendition of the piece.

Guernica: I noticed this particularly when I saw Beauty of the Father at the Manhattan Theatre Club—that the play was taking place in Spain and the people were Spanish and speaking English with Spanish accents. Does this often happen to your plays?

Nilo Cruz: That was a directorial choice. Michael Greif felt that he always wanted to be reminding the audience that this was not America, that the passion of these people, that this kind of behavior is not a behavior that you see in this country. This kind of love that these people feel for each other, according to Michael, you would never see in this country. This is a particular group of people that have nothing to do with the United States. And he always wanted the actors to use an accent to remind people that this was not happening here. Now I tell you what I like. It’s not an accent. I like inflections. For the actors to use certain inflections that capture the flavor. If you notice, I have a slight accent, but really my inflections are Latin more than anything. So I like that instead of an accent.

Guernica: Did you say that to him?

Nilo Cruz: I did say that to him, but he felt that it was important to have an accent.

Guernica: Were they Spain Spanish accents?

Nilo Cruz: Well, the problem was we had one actor who really didn’t know, the accent was completely wrong. He was not even a Hispanic actor, he was an English actor, and he just couldn’t get the accent right. You could really tell. It’s very hard to get… without falling into a stereotype… I did have problems with that production.

Guernica: So if a situation like you had with this actress in Spain happens in a rehearsal period in New York, and you’re not the director, how do you manage to work with a director?

Nilo Cruz: Well, the good thing about theater in this country, one of the good things, is that the playwright—I mean, we are playwright-oriented theater in this country, unlike Latin America. Latin America is more director-oriented. But here in this country, we do have a say, especially in the beginning, when the play is being discussed around the table. We talk about the play, and the actors listen, and there have been cases, like you’re saying, you disagree on something… I mean, actors don’t usually tell you what they’re going to do, they do it. Of course, you try to speak with the director and say, “Is there any way you can bring this actor to do something different?” You try as much as you can, but then, you also have to be open to interpretation…

Guernica: Have you ever written for a particular actor?

Nilo Cruz: Yes, I wrote for an actor at the Asolo Theatre. It was a commission in Sarasota, Florida, for the Ringling International Arts Festival. I wrote for an English actor there who’s really brilliant with language, and I thought that I should write a role for him. It was spectacular. It’s my new play called Hurricane. It’s really interesting because it’s a mix… He’s European. The actress who played the wife was African American, and the boy was Latino. It was really great. And I thought, “Oh, God, this is the future of theater, especially in this country.” I thought it was really good for me. It was a departure for my work. I’ve been writing more about Latino characters, and here I was writing about a European man, and the wife could be Latino or African American, but I loved the way that it was… changed the title, it’s called Aperecio and the Hurricane.

Guernica: Do you ever try to protect yourself as a playwright? When you go to publish and say, “Oh, this should be pronounced like this or the type of actor you cast should be like this”? Some playwrights do that when they go to publication. Like a guide for future productions.

Nilo Cruz: I’ve had a few notes here and there. I don’t overwhelm my plays with notes, because it’s not the right thing to do. If I feel something is really important, I might just write a little note.

Guernica: I’ve noticed you do one thing, which is you will write a line and then the next line doesn’t follow it on the same line. It follows it underneath.

Nilo Cruz: Like a poem.

Guernica: It suggests a slight shift or a slight…

Nilo Cruz: Not really. I think it’s easier on the eye… I actually cut my sentences a lot too. I’m very aware of the actor, giving them too many words—just a mouthful of words—it’s difficult sometimes for an actor. So I’m kind of aware of breaking sometimes the line, the sentence with a comma where maybe there wouldn’t be a comma there. Just to give a breathing space for the actor, just to be aware of that.

Guernica: During rehearsals, do you work with designers?

Nilo Cruz: I have in the past. But I really think I want to do more of that. Because I’ve seen productions of my plays ruined by the set design. As a matter of fact, I recently did a play that I was very unhappy with the set designer. I really think that the set design really bogged down the production.

Guernica: What do you do? Do you just say, “No, no, I really can’t even look at this, it’s terrible”? Or do you realize too late?

Nilo Cruz: The real professional theaters, you know, have a dialogue with you and with the director. You come in before and you discuss the set with the designer. Like a place like The Public Theater, absolutely. You sit down and you talk.

Guernica: Do you have veto power? Do you say no?

Nilo Cruz: I’ve never done that, but, I think, yes, you can. Absolutely.

Guernica: Were you consulted at any time? Did the director say to you, “This is going to be the design”?

Nilo Cruz: I was consulted at one point, but it was not a mock-up. It was like a really rough draft, and I had no idea what was going on. It was one of those computer kind of drafts, and it was kind of an idea of what was being done. I really love mock-ups, you know, a model, because you really have a sense of the space and how it functions in the third dimension.

Guernica: What about critics? How do you relate to them? Do you listen to them? Do you read them? Did you ever learn from anything a critic ever said?

Nilo Cruz: It’s something that I’m always torn with, the critics. You know, obviously, I’ve had bad—the production of Dancing on Her Knees… that play was completely destroyed by the critics. All the critics hated it. It was completely destroyed. It was only Ben Brantley that said something about, “This is an important voice in the theater.” But what I find is it’s very confusing when one critic tells you one thing and one tells you something completely different. Unless all the critics agree on parts of the play that just didn’t work.

You know, the problem with that is I’m not a victim kind of writer. You know what I’m saying? That would be a choice. That’s not me.

I have stopped reading reviews, to be honest with you. Because I find writing is all about courage. You must have courage when you start writing a play and you cannot have the voice—you must write things out. You cannot have the voice of a critic telling you, “That didn’t work in that play, you cannot make it work in another play.” It’s all about experimenting. Every time you do a production, it’s an experimentation. Every time you write a play, it’s about experimentation. I just don’t want that voice lingering in the back of my mind when I sit down in my room to write a play. So what I do is I call my agent and say to her, “Tell me if the review is positive or negative.” And there’s been times too when I’m sort of intrigued what they had to say, but the problem is that voice stays with me for a long time, especially if it’s a bad review. You know, it’s a slap in the face. It’s almost like someone telling you your child is not normal, you had a miscarriage. The voice stays with you. Listen, more than anything, I want to celebrate what’s there, the fact, you know, the accomplishment of getting a group of people, getting a theater. It takes a lot of work to get a play mounted. The effort from the actors, the theater, the money that goes into it. In the end, I just want to celebrate what’s there. I want to stay with that feeling inside of me.

Guernica: When you won the Pulitzer Prize, has that influenced your career, your work habits, anything? In a good way, in a bad way? You started saying that everyone knows Anna in the Tropics and no one…

Nilo Cruz: I think that the Pulitzer Prize is definitely a blessing, but it’s also a curse. Because I think that it is a blessing because the work gets more exposure, especially that particular play and then other works of yours too. And then it’s a curse because people anticipate that you will write another play like Anna in the Tropics. I think it’s really wrong because, you know, I think, as a writer, I’m in a process and I’m somewhere in that process, and I need to continue to develop. I’m not interested in repeating Anna in the Tropics. Anna in the Tropics is what it is, but every time I write a play, I find that what I have to do is learn the rules of that new play and what are those rules and what is that world about. It’s not that I come in and I project a set of rules to the play. No, I have to learn what are those rules. And I think being open to it and not repeating formulas and what worked in one piece and what didn’t work. You know what I’m saying? I’m not interested in formulas. I think that’s the problem with Hollywood. When I’m seeing a Hollywood film, I’m so aware of the formula, of the cliché. OK, this worked in another film, therefore, it’s going to work in this one. And I think it’s very dangerous territory, and, therefore, I don’t want to repeat myself in the same way.

Guernica: Did you get Hollywood offers?

Nilo Cruz: Yes. At the beginning, yes. I had to have to a conversation with Peregrine Whittlesey, my agent, and I said, “You know, I struggled for many years, as you well know, when I used to live at New Dramatists, to get to where I’m at and to do the work that I want to do for all of sudden, to do something that is not related to my sensibility as a writer…” Yeah, we were getting offers—things that had nothing to do with me, that didn’t interest me.

Guernica: Were they just, “Oh, well, he’s the Hispanic writer”?

Nilo Cruz: Yeah. To write a film about basketball. I don’t even like sports.

Guernica: Do you see yourself as having strengths that really guide you and weaknesses that you have to struggle against?

Nilo Cruz: Yeah. I mean, I don’t want to repeat myself. Even though that… If you read some of my plays, if you read the body of my work, you can see that these are my plays. I think I have a certain kind of style. I think at the same time, I’m aware that there’s certain things that I did as a playwright in certain plays, and again I try not to repeat myself, even though I have a certain kind of sensibility, and I tend to gravitate toward certain things, you know.

Guernica: So that’s your strength?

Nilo Cruz: No, well, it’s my weakness too. It’s both.

Guernica: The pull toward perhaps repeating yourself?

Nilo Cruz: Yeah. It’s both my weakness and my strength. How to learn not to repeat myself in the same way. Yet, it’s your oeuvre, it’s part of you.

Guernica: Do you believe, as some people say, that a writer has one story and just tells it over and over again in different ways?

Nilo Cruz: I don’t think so. I’m interested in human behavior, so I might explore the subject matter in certain ways that maybe other writers wouldn’t. For instance, my last play, The Color of Desire, is about obsession, and I chose to write it in a poetic way. Maybe another writer would have written it in a more realistic way. So even though it’s a subject matter that I had never written about before…

Guernica: When you look at your writing, in terms of an evolution, form and theme or in style, is there anything in which you can see an arc?

Nilo Cruz: I’m very intrigued by this new play I’ve written. I’m interested in multiculturalism in my work. That’s something I had not written about before. So it’s a departure for me. Because I think the world is that way. I don’t want to write about just one group of people but explore the others and what they have in common with each other. That’s a change. That’s my arc.

Guernica: I know that we talked a little bit about how your characters think and feel in Spanish but speak English.

Nilo Cruz: I sometimes incorporate Spanish into my work.

Guernica: Do you find yourself frustrated when you write the dialogue in English instead? Or is it something you’re so used to doing?

Nilo Cruz: I’m so used to doing it. But sometimes, for instance, now with this new piece, I’m enjoying so much doing the translation into the Spanish language. It’s a different way of falling in love with the piece all over again.

Guernica: I mean, sometimes, you just can’t say it in English.

Nilo Cruz: For instance, I’m trying to capture some of the rhythms. I originally tried to capture the Spanish rhythms into the English language. But when I write it in Spanish, I have to think of the syntax of Spanish, which is very different.

Guernica: Why don’t you write a play in Spanish?

Nilo Cruz: Why don’t I write a play in Spanish? I am. I’m writing an opera at the moment in Spanish. I’m writing an opera about Frida Kahlo in Spanish. Right now it’s through a Carnegie Mellon Foundation grant. We have a residency at Whittier College. I’m working with a composer named Gabriela Lena Frank, who’s Peruvian. So that opera I’m writing it in Spanish, but I’m also translating it into English language. So I’m back and forth. Again, the whole thing, there’s something about the English that informs the Spanish and the Spanish informs the English.

Guernica: You’re your own editor.

Nilo Cruz: I am my own editor, which I would love to do that. I just wish I had more time. Just to go back to these plays and do that kind of work, I just don’t have enough time. Also, at the end of the day, you just say, “Enough, I need to go into new territory.”

Guernica: Do you get to look at the Spanish translations?

Nilo Cruz: Well, I tell you, for Anna in the Tropics, because I was so busy when Anna in the Tropics got the award, that immediately there was a producer in Spain that wanted to do the piece in Spain. And he did a translation of the piece, but it was Castilian Spanish, which is very different from the Caribbean Spanish in Cuba. So I had to go back, I had to look at his translation and make it into Cuban Spanish.

Guernica: How did it work for the Spanish actors?

Nilo Cruz: They were fine. Some of them couldn’t really capture the Cuban accent, so they did it in kind of neutral Spanish.

Guernica: Do you find that you experience a lot of xenophobia working as a playwright?

Nilo Cruz: Yes, all the time. Especially in my last play. Especially from one critic, it was complete xenophobia.

Guernica: How do you work with that? I mean, you talked a little bit about working with dramaturgs. Do you think about, how is an American audience going to perceive this?

Nilo Cruz: I feel like I have to be a walking encyclopedia—I constantly have to be explaining myself—especially when I do table work or when I’m talking to a dramaturg about, you know, the culture, but also what I’m trying to do as a writer in this particular play. You know, you have to protect yourself too.

Guernica: But you don’t want to write a play about the situation. I mean, a writer might. You know, a Hispanic writer might write a play about how xenophobic the culture is. But that doesn’t sound like you.

Nilo Cruz: You know, the problem with that is I’m not a victim kind of writer. You know what I’m saying? That would be a choice. That’s not me. I’m all about celebration, not about victimization. There are other people that do like—and it’s great that they do that. I’m not that kind of writer.

Guernica: Are there any Spanish dramaturgs coming up in the world? Are they trained?

Nilo Cruz: Yes, there is a really good one. He’s from Spain. He is Juan Mayorga. Way to Heaven is the name of the play. It’s been done here in New York, at Repertorio Español. He’s really a wonderful, wonderful writer, Spanish writer.

Guernica: I was asking about dramaturgs. Is there a Cuban or a Mexican dramaturg who could work in this world…

Nilo Cruz: It doesn’t exist in Latin America. It only exists here and in France, in England. I agree.

Guernica: There are some people who think dramaturgs shouldn’t exist at all.

Nilo Cruz: But I like dramaturgs. There’s a couple of dramaturgs that I’ve had problems with in the past. But, for instance, I dedicated my play Anna in the Tropics to a dramaturg. Janice Paran from the McCarter Theatre. She was very good, and I dedicated my play to her, so imagine the impression that this woman made on me. I know that there are all these terrifying stories from playwrights working with dramaturgs and all this stuff. You know, you have to listen, and then you also have to, “OK, I agree with this, I don’t agree with this.” Just go and do your own thing. You might get frustrated sometimes. For instance, I was working and I had done a translation of a classic from Spanish to English, and I was being asked to fill in blanks of certain things. I said, “Wait a minute. We’re talking about a classic. You don’t do that with Shakespeare. You don’t add information. You don’t do that with Shakespeare. Why would you do this with…? Because it’s different culture?” And they said, “No, we don’t know this way of being in this country.” Anyway, I was shocked.

Guernica: Do you feel sometimes as a playwright, when you’re writing about a group that you’re a part of, a responsibility to represent that group?

Nilo Cruz: Yes, to a certain degree. But I don’t like that… you know, I can’t be the voice of the people.

Guernica: But you’re expected to be?

Nilo Cruz: Yeah, I think there’s certain expectations, but I don’t want that cross to bear at all.

From The Playwright at Work: Conversations by Rosemarie Tichler and Barry Jay Kaplan. Forthcoming from Northwestern University Press, June, 2012. @2012 Rosemarie Tichler and Barry Jay Kaplan