It always seemed to be raining that April we lived in Nashville. The sky would clear briefly. Redbud blossoms would burst, pink, on trees’ grey-satin branches. Cardinals would holler from newly leafed shrubbery. Robins assured us of spring’s welcome arrivals. Then the rain would start again, saturating lawns, backing up drains.

“I can’t tell you how many worms I saved on the way home,” I’d told my husband and daughter the night before. I’d walked the mile from work in a break between downpours. Along the way, stranded earthworms writhed on the sidewalks, their tender underbellies caught on rough concrete. “I think there must be so much water that they’ve pushed out of the soil and are looking for a place where they can breathe,” I said.

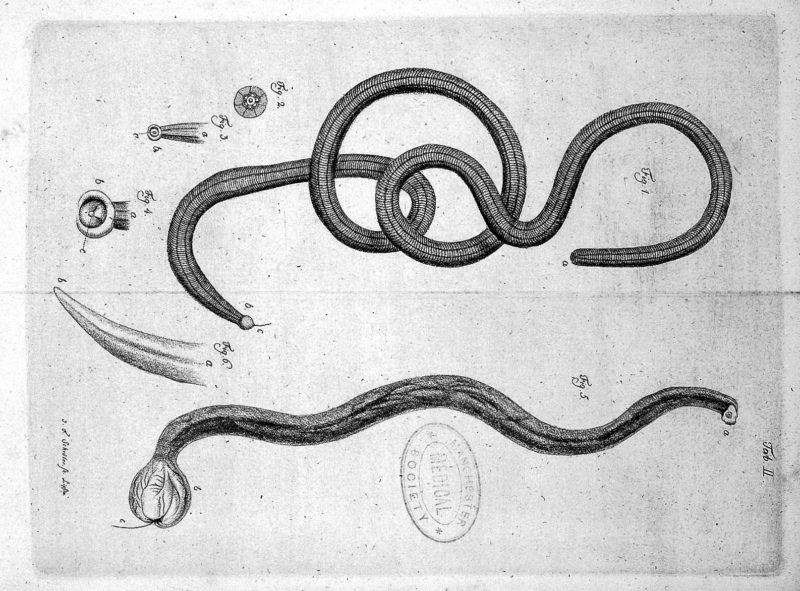

Earthworms breathe through their skin. They access oxygen in air pockets they create as they wiggle underground. Between pockets, they also construct tunnels that allow roots to penetrate soil and access nutrients. As they go, they eat organic matter in dirt and poop it out (gardeners call worm poop “worm castings”) to help build the productive, complex material we call soil. All this supports the vibrant floral displays we were beginning to see above ground. If I love the life that greets me at my eye level, I should love equally the workers who help make such life possible. But their tunnels can fill with water during heavy rains, and oxygen is a thousand times less available from water than from soil. After a storm, earthworms are forced to the surface, perhaps so they don’t drown.

“But sidewalks aren’t safe for them. Are they?” asked my daughter.

“No, sweetie, “I said. “They are certainly not.”

At recess the next day, worms swarmed the asphalt of my daughter’s playground, curling and pushing and sliding against the black tar. She pinched red wigglers between her thumb and forefinger and carried them to the dirt bed around a blue ash tree. “The teacher made me run laps around the playground,” my daughter told me after school, “because she caught me in the dirt touching worms.”

Earthworms need moisture, and so tend to stay underground, digging deeper and deeper to find wet earth during seasons of drought, but when it rains, some researchers contend, adult red wrigglers surface to slither more quickly to new ground. Such migrations are foiled by concrete and asphalt, the hardscapes of our built world. My daughter wanted to help the earthworms imperiled on her playground. She lifted stranded worms and carried them to safety. She watched them push and wiggle, tucking deeper and deeper into the soil they were helping to build at the base of the tree. She didn’t hear the teacher the first time she told her to stop.

My daughter told me after school that day that the teacher said she shouldn’t have been touching worms. “She said worms are disgusting. But they aren’t. They’re amazing, I think.”

I pulled her out of that school the very next day. I had just finished the job that took us to Nashville, and we’d been wondering when we were going to head back home.

So much of the world’s fertile splendor is thanks to soil, thanks to worms. I won’t have my daughter taught to fear the lives that help us live our own.

We arrived home in time for the intermittent May showers that hydrate the Northern Colorado soil. All the way to school and back, my daughter and I rescued writhing red worms.