I’m planting tomatoes in a new spring, fresh out of sequestration. I’m mixing compost into soil, hopeful this time, after the ruin of last year when, during our mass shut-in, my attempt to cultivate life in a garden bed did not go as planned. I’d been sending my children off on alternating weekends with their father, his attendance in our house an assignment I failed. In solitude, in opprobrium, I planted the seeds: tomatoes, asters, twining melons. I needed life, or signs of life, some exchange of chemicals with other living elements that might respond or succeed.

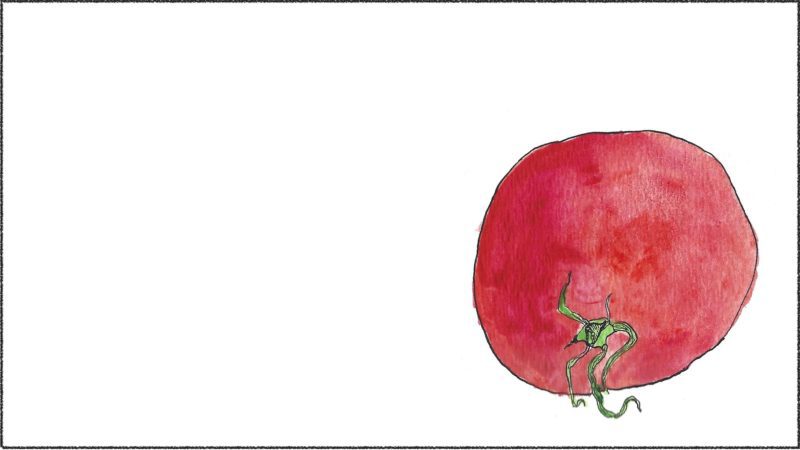

But something went very wrong with the tomatoes. Where green pods should have emerged from flowery sockets, where they should have darkened to red like tiny flushed faces, there was only a forest of leaves. The cantaloupes grew and were eaten, the cucumbers amassed all summer on their vines, but on the tomato plants, on the Sungolds and Five Star Grapes “sixty-two days indeterminate”—an easy number of days to wait for a tomato, I had thought, when we were all waiting for life itself indefinitely—nothing would come.

My sister was my witness. She came on a Friday when my children had gone, her three-year-old on one hip, a pen-stained canvas tote on the other, the sort we both carry everywhere—stamped with a bookstore logo, jammed with a desk’s worth of work. Her new poetry manuscript was smashed inside. It weighed as much as a squash. In a trance of assemblage, she formed piles of dog-eared reference books around my kitchen and living room for days. They looked like the anthills across the backyard that had begun rising in sporadic inflammations of pilled dirt, shivering with tiny lives I wanted to rake over. But ants are critical for seed dispersal and industriously aerating the soil. I’d been learning all about it. Disoriented, they’ll march in a circle until they die.

This is not unlike a family interned in a plague, its system gradually unsteadying. That first night, I heard my sister’s child crying for a balloon in her sleep and woke to the palpable absence of my own. The windows were open to the backyard; a fat moon hung over the tomato plants. I listened a long time for the coyotes in the field, and the voices that are usually so close it’s like I’ve eaten them.

The tomato is a nightshade, a relative of the poisonous belladonna. It was regarded with suspicion by early botanists and relegated to a table ornament for centuries. “You need an entire life just to know about tomatoes,” the Spanish chef Ferran Adrià says. The fruit had many complicated years, vacillating between “love apple” and “poison apple” across the continents, getting blamed for the deaths of wealthy Europeans in the 1700s when it was served, unwittingly, on lead plates. It’s a bristly history, but I’d eat them on anything. The thought in early summer that I could cultivate dozens of my own made me feel like Josephine Bonaparte growing two hundred and fifty varieties of roses in exile.

The tomato is a nightshade, a relative of the poisonous belladonna. It was regarded with suspicion by early botanists and relegated to a table ornament for centuries. “You need an entire life just to know about tomatoes,” the Spanish chef Ferran Adrià says. The fruit had many complicated years, vacillating between “love apple” and “poison apple” across the continents, getting blamed for the deaths of wealthy Europeans in the 1700s when it was served, unwittingly, on lead plates. It’s a bristly history, but I’d eat them on anything. The thought in early summer that I could cultivate dozens of my own made me feel like Josephine Bonaparte growing two hundred and fifty varieties of roses in exile.

Instead I was like Gertrude, my sister’s chicken back in Vermont, who’d grown broody and distraught, only wanting to sit all day on her eggs that would never hatch. My sister was coaxing her out of the coop in the mornings to drink water with the other hens and walk in the sunshine, trying to cheer her up, like Vanessa taking Virginia Woolf out of her bedroom when she was too depressed to walk in the garden. We are biologically driven to make more of ourselves, and propagate the earth, and steer our sisters from madness.

“The single feature identifying even the wildest wild garden is control,” I’d read on a gardening site when the plants were still only seeds in packets. But what did it mean to control a garden? Was one expected to control not only the landscape but the forces of nature as well, the nuclear, the electromagnetic, the “heavy rains [and] cold nights that come so often here” as Louise Glück writes in “Vespers”? “All this belongs to you,” she says, presumably to god. Her tomatoes are suffering from blight—too much rain, an early frost—and their black spots quickly multiply down the rows. But mine had no telltale malady. They failed in mute repudiation. The more I relished and tended to them, pinching and feeding, dragging their pots around the yard with the sun, the more errant they became. Instead of fruit, they grew huge leafy offshoots like national flags.

When we were kids, our mother cut beefsteaks, one of the largest tomato varieties, into enormous mouth-size quarters, and we ate them with Italian dressing. This constituted dinner. In our house, time wasn’t wasted on food. “Wolf peach,” she might have said over her knife, my mother who knows more words than anyone, referring to Lycopersicon, the Latin word for tomato.

There was plenty of time for us to do nothing but sit at home and grow, our danger and sweetness contained like a wolf peach. There was a slanted psychology to our education, our grandfather’s suicide disorienting generations, and years punctuated by erratic instructions on endurance and loyalty. Any gardening book will tell you that plants grow better near other plants. They are able to feel each other, and give off vibes, some scientists believe; underground, there’s an acoustic exchange. They sense drought, cold, heat, touch. They know one another’s distress.

There was plenty of time for us to do nothing but sit at home and grow, our danger and sweetness contained like a wolf peach. There was a slanted psychology to our education, our grandfather’s suicide disorienting generations, and years punctuated by erratic instructions on endurance and loyalty. Any gardening book will tell you that plants grow better near other plants. They are able to feel each other, and give off vibes, some scientists believe; underground, there’s an acoustic exchange. They sense drought, cold, heat, touch. They know one another’s distress.

Our grandmother was waiting up when the phone rang in the night with the news her husband had hung himself in his rented study. They were in Cambridge on sabbatical; when she took the call, their three daughters were asleep in the next room. “To be alive is to want to remain alive,” the physicist Marcelo Gleiser says, explaining what discerns forms of material organization. This is the difference between a plant and a star. My grandmother brought them back to America on a ship and locked the door for ten years.

Now, when my sister and I arrive at each other—her house, my house, our mother’s Vermont clapboard with no proper heat—we’re blanched from confinement, needing fellowship and solitude. “Can you watch her for just—an hour?” my sister will say, handing me a snack pouch and hurrying away with her paints or her poems. I must report failure, I sometimes think, hearing Glück, hearing my own distant dreams like plants under the gorging aphids.

“Play with me!” her daughter called that week from everywhere. The hot air in my backyard hung still as a greenhouse. My own daughter, an only child for five years until her brothers were born, used to beg me to sing “three, six, nine, the goose drank wine” over and over on the city bus to preschool. She’d fall asleep in my lap at night while I’d grade papers or write, always filling the only space my hands had to go. When I pick up my niece, her soft underarms are familiar.

One morning we filled the watering can and made our way from plant to plant, my elbow underneath her, her toes in my pocket, and I was humming “Hi-lily hi-lo”, my favorite song at three, when we heard a sudden, anguished moaning. “What’s that sound?” she said, looking toward the woods. We climbed into the car to go investigate, thinking it might be the 350-pound bear the farmer down the road saw the day before with my bright yellow birdfeeder under its arm. But it turned out to be some newly arrived calves dropped in another neighbor’s vacant field, which abutted mine. “Sorry about the noise,” my neighbor said, looking at the disoriented herd. “They’re weaning. Taken from their mothers this morning.”

When I was ten and my sister was four, a farmer brought a truck of young cows to the field across the street from our house. It was usually empty—too muddy for much of anything—but the first night they were left there motherless, it thundered all night with their cries. “Just cruel!” my mother shouted while my sister and I lay in bed shivering. Some years later, we sat in an emergency room with our arms linked and our leather boots side by side on the floor, listening to the moans of other nighttime emergencies while we waited for her to be admitted. My sister, in despair, had hurt herself and was poorly bandaged back together but carrying in her bag some of the most exquisite drawings I’d ever seen her make. The one I remember best was a tall bird bending over and eating its own body.

Was my barren tomato plant turning on itself? Its refusal to grow a single fruit on any of its healthy stems felt willful and resigned, an expression of ancestral rejection. Was it a psychic deficiency? Was it me who had failed? I read in an old botany book from my mother that a tomato shouldn’t need much. It will self-pollinate and endure with only an occasional bee or gust of wind. Some types tolerate extreme cold by growing hair. But the stems on my own plants were plain and rigid, and they didn’t sprawl like the softer limbs of their decumbent ancestors. “Tomatoes are supposed to be easy!” I cried to my sister, yanking off my gardening gloves, the goatskin tips reinforced to prevent premature wear. “They should withstand all kinds of stress!”

Was my barren tomato plant turning on itself? Its refusal to grow a single fruit on any of its healthy stems felt willful and resigned, an expression of ancestral rejection. Was it a psychic deficiency? Was it me who had failed? I read in an old botany book from my mother that a tomato shouldn’t need much. It will self-pollinate and endure with only an occasional bee or gust of wind. Some types tolerate extreme cold by growing hair. But the stems on my own plants were plain and rigid, and they didn’t sprawl like the softer limbs of their decumbent ancestors. “Tomatoes are supposed to be easy!” I cried to my sister, yanking off my gardening gloves, the goatskin tips reinforced to prevent premature wear. “They should withstand all kinds of stress!”

“Stop pruning them,” my mother said on the phone. Her tomatoes, purchased as seeds on the same day as mine, were fat and crowding—so many clusters, she said, she’d had to tie a rope to the tomato cage so it didn’t fall over. She is not an over-tender; my mother does not indulge. She waters her big pots once in the late morning and then disappears to play six or seven hours of phone Scrabble and bead her antique lampshades.

I imagine the total loneliness that made her. All summer I touched the cucumber plants, understanding more, examining their strange antennae, sensory organs that feel every movement in the air. They reach for steadiness; they climb toward light. This is what distinguishes the living from the non-living: something alive will respond to its environment. It will also use energy, attempt to reproduce and work to survive. When the cucumber shoots first began to grow tentacles that reached into the air like slight, slender fingers, I was intrigued and creeped out. It was like being pregnant for the first time and reading those descriptions about what your baby looks like right now inside you. By mid-summer, the feelers had worked their way around every trellis, rock and plant, hoisting the dangling gourds higher. The leaves opened like wings; the whole thing seemed ready to lift into flight.

We don’t have such feelers, but the human eye, its cornea and lens, is a sensory antenna on the scale of organs. To be a mother is to exhaustively transmit and receive, amplify the sensory structure; feel too much. I can see the antenna-mother as if sketched by Roz Chast: straight as a rod, blinking in the electrical field of her many imagined hazards.

I took a photo of the fruitless tomato plant and brought it to the farmer down the road who kept a small store in her barn. “So strange,” she said, zooming in. “All this green and not a flower.” Her husband came in from the field while I was paying for six ears of corn and she showed him the photo. “You’re spoiling them,” he said. She agreed. “No more Miracle-Gro! And quit watering for a few days. Everything needs stress.”

As I was walking out, she picked up an overturned plastic container beside the barn: the last tomato plant for sale. It looked dead—dry as wood inside and only a few minuscule leaves—but up close, yellow petals had flowered at a few tips and a couple of tiny green globes were forming on the branching stems. Plants survive as a species because they flower and produce seeds, she told me, even when they can’t survive themselves. Take it home, give it some soil and water, then leave it alone.

As I was walking out, she picked up an overturned plastic container beside the barn: the last tomato plant for sale. It looked dead—dry as wood inside and only a few minuscule leaves—but up close, yellow petals had flowered at a few tips and a couple of tiny green globes were forming on the branching stems. Plants survive as a species because they flower and produce seeds, she told me, even when they can’t survive themselves. Take it home, give it some soil and water, then leave it alone.

Back on my land, site of my crash course in biological mutualism, my sister’s manuscript was spread across the kitchen floor, each poem basking in the sunlight with H.D. and Nussbaum, The Letters of Virginia Woolf Volume IV; an old Farmer’s Handbook from the 1920s with an extensive glossary of fertilizers. The kids were home and making a cake. They were filling spoons with sugar and soda, exchanging energy, my teenager perched on the countertop like an overbearing sun. “I paid her twenty bucks,” my sister said, stretching. The Farmer’s Handbook sat beside her with my bookmarked pages; it was, it occurred to me, a kind of manual for patience and stamina, as suited for a struggling farmer as for an individuated mother. It details dozens of types of crops and the supplements they need for growth and productiveness, the expected periods of dormancy; the likely disruptions of storms.

I carried the new tomato plant I’d been instructed to ignore and positioned it close to the others in the backyard, for company. I resisted the desire to encourage it. I didn’t trim the dead leaves or pluck the suckers. In a few weeks, the cold would dip down and end everything. The year would be an experiment. That summer, I hadn’t remembered how I left my daughter alone when she first discovered books, their nitrogen words, their phosphorus pages—I’m remembering now. By September, a green tomato had swelled, then shaded slowly to gold, then red. Then loosened itself free.