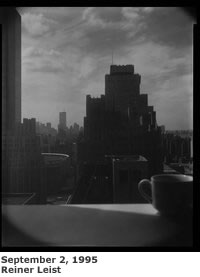

Since 1995, Reiner Leist has taken a photograph of lower Manhattan through the window of his loft on 37th Street and Eighth Avenue nearly every day he has been in New York. Primarily shot through a full-plate camera dating to the 1890s, the photographs in this project, Window, are a grainy and human counterpoint to the mountain-scale city views.

Leist’s images offer two contrasting timelines: the quickly shifting personal landscape evidenced by objects on his windowsill in the foreground and the city’s continuous but more gradual-seeming evolution in the background. The photos are taken in various weather conditions and at different times throughout the day, but the World Trade Center’s twin towers anchored the city views for the project’s first five years. Along with so much of our city and national life, the historic and world-changing events of September 11th also indelibly reshaped Leist’s project.

Among a bulk of over 2,200 photographs, 249 appear in the book “Window/Eleven Septembers,” published this month by Prestel and on view in a show at the Julie Saul Gallery through October 14. Simultaneously, a show at Staatliche Museum in Berlin presents the body of work in its entirety.

[Interview by Dylan Fareed]

Guernica: How was the decision made to use the reference point of September 11th as the organizing principle for the presentation of Window/Eleven Septembers in the book and New York show – both titled “Eleven Septembers?”

Leist: The main title of the work is ‘window’ and so is the title of the exhibition in Berlin, which shows all the images taken over 11 years. It is 12 times the size of [the New York Gallery] in a big space, and that’s the main work. The decision to isolate the September images for the publication and for the exhibition in New York is a tricky one, and it’s something that my gallery was not so comfortable with and that I was at first hesitant about, but I have since embraced it for several reasons.

First when you have lived with this project for so long, you know you don’t always have the opportunity to show the entire piece. There has to be some selection criteria. There are very few spaces where you could show 80 yards of an installation. Even the biggest commercial galleries could not be big enough to do that, and very few museums could make that space available. If you make selection criteria, what would it be? For me, it was important you could see the work both horizontally and vertically, meaning [you could] compare days over years and chronologically see the work. It seemed to make sense to isolate a month and look at it over a period of 11 years rather than isolate one year or two years that are chronological because then you can’t compare vertically if you will.

I look at the work and see a huge gap in summer. I was typically gone in the summer, so the densest area of imagery was in the fall. So September and December were the two months with the most number of images. When I was out of the city, there was no image. It made no sense to select July and have 40 out of 330. So the first choice was originally to be September or December. Then my publishers and editors felt that the project had gotten so loaded with September 11th (since the subject is on the building and the World Trade Center was the center of the image) that it made sense to take it up as reference. It is not called “September 11” but 11 Septembers so it’s a rebuke. It’s about more than that. It’s about the tension of two aspects, and it’s… I’m happy with it.

There was a big gap before [September 11th] because I had gotten tired of the project in some ways. I had been doing it for six years, five or six years, and I had a job that moved me out of town to Cambridge, and I’m not entirely sure…I’m not sure that if September 11th hadn’t happened that I would have continued with the same intensity since it threw the project for a spin. Also what is important for the project is the relationship between what you set out to do and what actually happens. For me, one of the intentions was to record changes that are subtle and minimal, and of course I wasn’t thinking of anything as dramatic and historical as what in fact did happen, so I think the project took over in a way that I could not have foreseen or anyone else could have foreseen so I think it’s a fair measure to make that the point of the title.

Guernica: Thinking about the way the images consistently juxtapose elements from your own daily life in the foreground with the indifferent city beyond, I wonder, was there an initial personal motivation for your starting this project?

Leist: Yes there was a very personal reason. It came out of a relationship. I had met a woman on a plane that at this point I wanted to share my life with. One way of staying connected was for me to send her an image and since she was living in Germany and I was living in New York, it had a very pragmatic reason, and it was also for me a reassurance that I was here.

It may sound bizarre. I had grown up in Germany, lived in South Africa for seven years and expected to stay there. Things did not turn out that way. I did move to New York.

You look out the window and ask yourself, “Where am I?” It was also an effort to hold onto it. You’re on a visa. You don’t know how long you can stay. It becomes this magnet of sorts: “I have to do this. I have to hang onto this.” So there are always multiple reasons. Some reasons will only become clear to me ten to 12 years later why I would be doing this or why I am doing this. It’s an exercise for my own life. It’s like meeting another person for the first time around. There’s a first impression that becomes much more detailed and in depth if you meet again and again. You may have to revise some of your first impressions and it grows.

It’s an exercise for my own life. It’s like meeting another person for the first time around. There’s a first impression that becomes much more detailed and in depth if you meet again and again. You may have to revise some of your first impressions and it grows.

Guernica: So how has the the weight of repetition changed your view of New York?

Leist: The answer is somewhat paradoxical. You know I came to the city in ‘94, started the project in ’95. It’s 2006 now. I’m in 12th year now. It starts to seem like a short time because you’ve done it for so long, and you realize on the one hand a lot has changed. There were a lot of changes long before I started, and there will be a lot more changes after I move out of this apartment or I die. It becomes a relative experience in that sense.

So would I like to do it for another 10 years? Maybe, I don’t know. How has the city changed for me in those ten years? I’ve always felt another tension for me is also knowing another person and having more time spent with that person doesn’t mean necessarily knowing a person better. It’s more detailed. Maybe you have questions about yourself: How well do you know yourself? What do you really want? What should you really be doing with your life? That stays true for me as well.

Looking at September 11 with all that pain and all that drama, I’m sure there were days in the years before where there was equal drama behind some of the windows on some of these streets: people getting killed, getting badly injured, getting hurt in other ways. There’s always that presence even though it isn’t always visible. The opposite has been present to me – people who make their careers [and] families here, who have a very important phase of their life in the city. You’re familiar with the fact that people come here in their 20s and leave in their 40s. They make their life here and move on possibly somewhere else because it’s such an energizing and fast-moving place. That has not really changed in that sense. It becomes deeper. I have a better understanding of what may hide behind what building or street as I’ve walked around the area, but it stayed somewhat mysterious. And it’s also, you know, stayed somewhat brutal. My first time in the city, I had ambiguous feeling about it. It was extremely open and the first time I got to the city, someone paid for a cab for me. I have never experienced that again—the most generous and positive people you can think of—and at the same time lot of harshness. It’s that irreconcilable mix that is always present for me when I look out that window. For me it’s a series about New York City, but for me it’s also a metaphor for life and for other places.

I’ve not just looked out the window. I did project that is called American Portraits where I traveled all around the country—remind me to send a copy of that book to you—where I tried to do exactly the broadest geographical exploration around the country in five or six years and see how different places inform somebody differently than someone in New York City.

Guernica: In the statement that accompanies the Berlin exhibition, Ludger Derenthal describes the oldest surviving photograph, a heliograph by Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre – his view onto the Boulevard du Temple from 1839. There because of the long exposure time needed, the buildings are in sharp detail but all of the commotion of the street scene – people, carriages, movement, energy – disappear. In the case of Window you photograph the exteriors of buildings and think about the personal lives of the people inside them – lives not depicted in the images themselves.

Leist: I think you can picture anything. I mean very often I find where the image needs to appear is in the imagination of the viewer so if what you’re talking about is in the image, it can’t really happen in the viewer’s imagination.

The viewer’s imagination – it may be visual or verbal, but I think that’s what really is the platform of our conversation, to see the other person’s imagination – it can’t all be inside the photograph. It can be one part of the conversation in the best case scenario. Of course, it’s certainly impossible for a photograph to really give a complete record of what is going on in the city or in a person’s life. Talking about American Portraits, when I met a woman in Key West who was sharing her life story with me, she showed me a pleasant photograph of herself with her family but she said, “Really my mother was an alcoholic and my life was in shambles. The only time I was happy was when I was at dance lessons.” The photograph was a complete lie – suddenly you have this tension between a verbal statement and this photograph or your idea of the photograph. I think that’s also hopefully the case in the Window/Eleven Septembers book – that you reference it with your own material – it’s just one subjective view of the city that starts to come hopefully alive with your own experience of the city.

Guernica: What are the limitations of one photograph over the limitations of 2000 photographs?

Leist: For me both avenues have their promise and both avenues have their limitations. Clearly I have made my choices in my work. I’ve always worked in series, but I don’t want to generalize at all about the medium. I think for others it works very differently. For me, I’ve always seen great potential in working in series a – maybe more like a writer prefers to work in long fiction rather than in short stories. I like the length and the serial approach – that is not to say that single images can’t be iconic and carry a different form of conversation.

Guernica: Do you find a tension between the individual image on its own and within the context of a series?

Leist: Of course there is a tension and, again, it depends on the experience of the viewer because no, not everything can always be in the image and in the consciousness of the viewer. Because the photograph by itself can’t do anything without you as a viewer. It depends on the context. Somebody who has lived downtown will view the same photograph very differently than someone who has never been to New York. It will certainly be a very different experience. I think that the series is for me a longer, more intense conversation rather than a shorter confrontation or encounter. By itself it doesn’t say anything about the quality. You can have 5000 or 10,000 images, and you can have one strong image that can change your view of the world.

Guernica: How do you feel about the momentum that a project exerts on you? There was a period you took off and then came back to it.

Leist: It was kind of a struggle. It’s a kind of power struggle in that sense. You create something that originally I said that “This is going to follow my life: when I’m here, I take a picture, and when I’m not here, I don’t take a picture.” Years into the project I find myself driving home, you know, at, like, ten-thirty at night. I needed to take this picture, and it started to take over my life in some way or another, and I realized friends leave things in the window because they wanted to be photographed the next morning so it’s starting to actually have an impact. And in a sense, it was interesting to see how the project took over, and then I’ve also rebelled against that and didn’t want that to happen. It’s still open-ended. What is really more important: what you intended or how life takes place? It’s an open-ended question

Guernica: …but the project is ongoing

Leist: It’s ongoing and the interesting thing for me is that even if you don’t take the picture, you’re still taking it. You cannot really stop avoiding it because it’s taken on…I mean, maybe I can give you another take on it in terms of the serial versus the unique or individual. I think things you do on a regular basis have much more impact on our lives than things we do once or rarely. How much you spend on coffee may have a bigger impact on your life than that $400 purchase you make once. In fact that $5 coffee may end up costing $2000 in a year. What we consider unimportant or what’s considered marginal may have more to say about us than what is extraordinary, and in that sense, I would use the word ‘paradoxical’ again, and that’s hopefully coming through in the series. I find that the ordinary and the routine are really provocative and tell more about our lives than those events we might normally consider ‘extraordinary’ like a birthday party.

Guernica: But at the same time, there are certain events that bend everything around them.

Leist: Very much so—and it happened.

Guernica: Could you tell me about the technical aspect of taking these pictures? When you come home late and you think, “I have to take this photograph,” what is it that you see yourself having to do?

Leist: To actually make the exposure range from a minute to five hours because of how much light is outside. A night exposure can take several hours. It’s a 19th century antique full-plate camera. The plate is smaller than 8 × 10 – conventional film to make images. So the camera is really boxy. I also use this one (gestures to a camera manufactured in the 1920s) for part of the series – similar in size.

Guernica: Do the photos from each camera look different?

Leist: Yes, they look very different. In 1996 you can see how sharp the images are. That lens was made in the 1920s, and the other lens was made in the 1890s. So in those 30 years, optics changed considerably. But then I found these images too photographic and too sharp, so I prefer the vignetting and the 19th century lens, and it also gave me a wider view of the city.

Technically, the real work happens after you take the pictures. I developed and produced every single image, and it’s been really grueling to do it for these exhibitions. The sheer number is daunting. Everything that takes you an hour to do…Multiply that by 2200. If something takes you a minute times 2200, how many hours is that? Everything becomes a logistical nightmare.

Every time you do something you try and make it better, but there’s just a limit to how efficient you can get. It just doesn’t get any faster when you have that number of images, and it’s the first time I’m starting to feel sympathy for Department of Immigration authorities who always make mistakes. If you have such staggering numbers, you’re bound to make mistakes and you’re bound to be overwhelmed, and now I understand better than I did years ago.

Guernica: Were there a lot of mistakes in the darkroom?

Leist: Oh yeah, in the book you see developing mistakes, all kinds of streaks and other problems, and it’s really about the physicality of the medium. It’s not a slick project at all. A friend of mine generously said, “They feel so hand-made.” They’re not cleaned up. They’ve retained their physical substance like film format. You take the sheet in your hands and process and contact it. It’s different from 35 mm or medium format film; it’s something physical.

To comment on this piece: editors@guernicamag.com