Sir or Lady (SL) and I met at an alternative weekly, where we both worked in the art department; I was the department assistant, SL a freelance graphic designer. By way of introduction he would shyly offer me things he thought might interest me: postcards, books, photographs. One of the first postcards he sent me was by the photographer Helen Levitt. It showed two colored boys on a street in New York, in the nineteen forties. One boy is facing the camera; the other boy’s back faces the camera. Their arms are linked. They look like two sides of the same coin. SL passed along a play: Ibsen’s John Gabriel Borkman. In it, twin sisters long to be loved by or control the same man. He dies. In the end, the twins accept being “twin sisters… of one mind.” Because of SL—he loved her work—I also read Gertrude Stein’s Ida: A Novel. In it, Ida, the heroine, wishes for a twin. She writes letters to her imaginary twin, also named Ida. “Dear Ida my twin,” one such letter begins. And continues: “Are you beautiful as beautiful as I am dear twin Ida, are you, and if you are perhaps I am not.” SL gave me a VHS tape: Chained for Life (1951). In it, real-life conjoined twins Daisy and Violet Hilton star in a fiction about their struggle for love, set against a show-business backdrop. No man can separate them, though; they’re emotionally “chained for life.” Then there was Thought to Be Retarded, written and designed by SL himself. It was based on a performance he’d done in collaboration with the photographer Daniel Lerner. Their piece was based on the story of Grace and Virginia Kennedy, the famous German-American twins born in Georgia in the early nineteen seventies, who developed their own language and were “thought to be retarded” because their parents, social workers, and speech therapists alike couldn’t understand them. (The Kennedy girls were themselves the subject of Jean-Pierre Gorin’s exceptional 1980 documentary Poto and Cabengo.)

He didn’t really know why he was here, in the world at all. He had no I because he had no country. SL and I had both grown up feeling that the language we spoke was somehow incomprehensible or fuzzy to those around us. He’d spent his adolescence on army bases in England, France, and Germany, while I had no direct experience with white people until I was a teenager. SL’s parents were middle-class American Negroes from the Midwest who went to work in Europe to escape, if it can be done, racism. (SL’s father taught college-level chemistry on various army bases, while his mother worked as an administrator.) But his father brought that racism with him. Like many men of his background, his racism was really counterphobic: He revered white people. That his only son couldn’t assimilate enough for his angry, continually disappointed father—an impossible task; SL was a black kid in a white world; no matter how much he was lauded or fucked over in that world, he would always be black—was just one of the small crucifixions SL endured for his father’s sake. Other nails and splinters: the irrefutable sense that he didn’t really know why he was here, in the world, at all. He had no I because he had no country. He would not have his maleness because that was a sick and diseased and controlling thing—like his father.

In the late early nineteen seventies, SL, a tremendous reader, began to hear bits of himself not in Piri Thomas or Eldridge Cleaver but in Shulamith Firestone, and Ti-Grace Atkinson, and Carolee Schneemann, and Robin Morgan: women who were of SL’s class, more or less, and had experienced, growing up, something akin to what he had known at the hands of a father: being subject to emotional violence because they owned you, you were their property. He and his mother had grown up in what Shulamith Firestone called “shared oppression,” The difference was she believed it: Wasn’t her pain the pain you suffered for family? Later SL would withstand mountains of pain for his family. But in the early nineteen seventies he did two things: He got out, if only he could get out. That is, SL moved forward into his future, but his past resented it. He had boundless hope, but his past thought otherwise. Leaving home, he would kiss white women, or they would kiss him, with no expectation and every expectation, and then—sometimes—he would turn to me and love me as he had been loved in his past, walking in the Black Forest or wherever, tagging along behind his parents in his Eton cap, wondering about the forest worms as he served as an audience for his parents’ follies, their seemingly endless marital drama of acceptance and rejection, a form of theater many mothers, for instance, try to justify by saying, We’re staying together for the kids’ sake. That’s the first lie of family. It’s never for the kids’ sake. Why has no mother, including Hamlet’s own, not admitted to her libidinal impulses, saying this crazy-ass dick or uncontrollable freak works for me, I could never do what he does in the world, be so out of control, terrible and boundaryless, I’m a woman, confined by my sex, prohibited from acting out because other lives, my children’s lives, depend on me, but still there’s my husband acting out for me, what a thrill as he crashes against the cage of my propriety. What no mother in history, including Hamlet’s own, has ever been able to entirely process, let alone admit: My husband may not actually be our child’s type.

From the first, SL and I were each other’s hall of mirrors, and is this me currently looking at my parents, or SL looking at his parents? Was it my mother’s competitive desire to make a kind of glued-together, unforgettable art out of her marriage—who could make a better thing out of it? Me or your father? Or SL’s mother? Was it SL’s mother or my mother whom we loved beyond her comprehension, equating her body with a thing to be manipulated by male hands, something that reinforced her idea of male authority, which she admired even as she did and did not admire her son’s repudiation of it, a rejection that made her ashamed of her need for it, and so there was nothing for it but to reject the son as weak, poetic, a loving pussy to be tolerated and sometimes reviled. Who could love her for having such thoughts? Who could say? SL and I were each other’s hall of mirrors, each a kind of Marvin Gaye in relation to our respective fathers, but SL got away, and left Europe for the United States. I can’t bear this part of the story, the he-got-away part, even if it was the best thing for him, and it was, because it presages his getting away from me, the very embodiment of his boyhood isolation.

I ate dirt until he came along. I had what they called the ringworm. I picked my scalp and there it was, underneath my fingernails, piles of sick. I was a preteen Caliban deformed by flaky skin; I had pus on my mind. My head was a compost heap. My fingernails dug into what they, the older people, called the ringworm, or eczema, and I sent shivers down my own spine—an erotic “pain” I could not wait to get my hands on. My gray woolen Eton cap was lousy with me. There was SL in his Eton cap and his forest of worms, and there I was in my cap, waiting until he came along. My contemporaries—other children—risked contagion if they touched my cap, let alone my diseased spot, which, come to think of it, looked a little like a woman’s private parts; boys spitballed it.

My infirmity sat on the back of my head, just above my neck. My ringworm was my cruddy friend; it had no other friends and so many enzymes, a dark flower could be forced in it. My ringworm was philosophical. It had certain ideas about the world, about me. One thing that made my ringworm sick was my interest in myself—an interest I almost never uttered in the company of the well. My self-interest was not founded on self-love but on fury over my scabby presence, which no amount of love, from my parents or siblings, could cure. Self-interest ran in my family. They could see me only as the cute extension of what they felt to be cute about themselves. If I expressed, let’s say, a dislike of marigolds, that shocked them: I was too cute to contradict flowers. I shut up early on and let my imagination run wild, or as concentrated as my patch of sick.

My ringworm was as infested with longing as I was. My body and soul were a sewer, briny and foul with sexiness. Daddy doesn’t like that about me, and I don’t like him, but my body craves him.

Daddy says that I am strange, that he never knows what I am talking about. When he comes to call on my mother, he says, Goddammit-what-the-hell-Jesus-Christ-aw-shit-for-fuck’s-sake, and Huh? whenever I open my mouth to speak; consequently, I rarely do. Daddy turns me on because he doesn’t think I’m cute; he makes me work for his admiration.

She is a gorgeous hysteric, as loud as the worst flower. She contradicts my family for me.

He knows that I spend a lot of my time at the big lending library at Grand Army Plaza in Brooklyn, reading books. What he doesn’t know is that while there, I also listen to recordings by grand actors reading famous poetry, prose, and plays as a way of learning how to speak in an authoritative, genteel way meant to captivate my father, like a pus-y siren. I listen to white girls such as Glenda Jackson as Charlotte Corday in Peter Weiss’s play Marat/Sade, because she is not genteel or cute in the role of the knife-wielding anarchist: She is a gorgeous hysteric, as loud as the worst flower. She contradicts my family for me. One of Charlotte’s interlocutors begs her to turn away from her various hatreds and “look at the trees/look at the rose-colored sky,/and let those horrible things pass you by/feel the warmth and the gentle breeze/ in which your lovely bosom heaves.” Charlotte cannot. “What kind of town is this?” she asks. “I saw peddlers at every corner…They’re selling little guillotines with sharp knives…and dolls filled with red liquid which spurts when the sentence is carried out. What kind of children are these? Who can play with these toys so efficiently? And who is judging? Who is judging?”

As Charlotte Corday, I can hate marigolds. Glenda Jackson’s ferocious tone encourages me to imagine Daddy dragging his big Daddy body toward me because I want him to, because I am, finally, all he could ever need: a person capable of screeching, How I hate the marigolds! He bites into my ringworm and eats the red, pused-out bits in the way my older sister ate the petals she pulled from red flowers: with relish. I am not a child. I am a judge. I have been made older through cultivating need, which feeds my imagination, the one thing Daddy does not have access to, the one thing I can make him a lovesick prisoner of.

But SL got out. In 1975, he returned to America on his own, ostensibly to attend college, although he never went. Instead he fell in with New York–based feminists, some of whom roamed the Berkshire woods naked with bow and arrow, looking for men to kill, while others stepped on the accelerator when they saw men crossing the road. In this world, SL became a wife, supporting a number of friends’ and lovers’ work while his own work took a backseat; it was the least he could do: He had had a father, and he would have no further truck with that. By the time I met him and longed to be his wife, SL sometimes described himself as a lesbian separatist. No man could have him.

I was attracted to him from the first because I am always attracted to people who are not myself but are. It was less clear why he was interested in me. I made him laugh, I suppose. Perhaps he enjoyed the fact that, in those days, I always looked like an old-school bull dagger, what with my thick neck, little gold earrings, no makeup, and hair cut short and shaved on the sides. Also, he knew, and chuckled over the fact, that I was a gay man who did not suck white dick: I refused on the grounds that the world sucked them off well enough. Most certainly he liked the fact that I came from an enormous family of women. He definitely liked hearing about my first-generation West Indian–American parents, who hadn’t been raised to be professional Negroes, and who didn’t know the first thing about how to keep up appearances: They’d never married, let alone lived together.

But, like SL’s father, my father disliked men, less because he wanted to control me—that would require a closeness he wasn’t in the least interested in—but because he found them to be invasive, childish, loutish tit grabbers—the very thing he was, and held his sons to be without knowing much about them. Once, after I’d won some prize in elementary school for writing a poem, my mother encouraged me to hug my visiting father; she knew he could not do it but she also knew I could not write that poem without him on some level; Daddy and his incessant, on-the-phone language was one source for my “art.” While I stood before him, rigid and blank, he took me in his great arms—my father was a big man; I would grow up to be a big man; I wanted a bigger man to hold me so I could feel, as a grown-up, what my father’s embrace made me feel: that I didn’t want to grow up to be a big man—and whispered: When I was your age, I didn’t like my father to hug me, either. SL understood all that. Or, rather, what it set up in me: a horror of my I, since that meant being a him—my father.

I loved his entirely adult attire; it relieved me of the responsibility of being an adult; in his company I got smaller and smaller, hungry for his protection. On one of our first dates together, SL and I took a walk. It was early spring; we had just finished work. SL was costumed in his usual striking manner: a stiff, ankle-length motorist’s jumper, blue-and-white-polka-dot tie, brown spectators, and a brown fedora. I loved his entirely adult attire; it relieved me of the responsibility of being an adult; in his company I got smaller and smaller, hungry for his protection. SL was a wit you didn’t want to cross. As we walked along, we started to talk about all the places we’d ever visited, or hoped to visit. In fact, in a few days’ time I would be off to Amsterdam to visit a friend. Rather offhandedly, I asked SL if he’d like to join me, have a lark, and to my horror he said yes. It was as if he were cursing me in a baroque, foreign language. What could it mean—his acceptance? Where was this: my father offering me a ride downtown—I was a teenager taking a summer-school class in mathematics—but before I could get in the car, he jumped in and slammed the door, called out, So long, sucker! as the cab drove off. Where was this: my father telling me I’d go from “Shakespeare to shit” if I didn’t stop hanging out with my teenage friends, indeed, if I had any friends. Where was my father doing this: refusing to stand up, let alone look at any friends I might bring home, especially if they were white, sometimes if they were women.

In retrospect, how could my father love me? I was that part of his self that wanted to write and would write but did not. I was that part of his self that wanted to love and would love but did not. Here was evidence of that: SL. He would go to Amsterdam with me. O Amsterdam, city of canals! He would listen to what I would write about even if it was derivative, or boring, and find something of me in it to support and praise. He would look for me in every part of Amsterdam because I loved it so, in every canal, in the city’s flatness, and in the waves that came up from Harlem, and the city’s famous tolerance, its clouds and herring. But how did he find me now, on lower Broadway? I was short-circuiting because of this information, so casually offered: He would go with me, and he would love me. Would he die because of this love? Would I? Would I have to eventually mourn this memory on lower Broadway, his scratchy-sounding duster, and should we travel to Amsterdam together, him and an entire country? His existence was too much. I fumbled and made an excuse: Oh, the place I’d be staying in was a friend’s, it was too small, maybe the next time, with better preparation? SL smiled. He knew enough about love—or, more specifically, about its offers and denials—to back off, say nothing, and smile.

After I returned from Amsterdam, he continued to connect to me through metaphor, which is how he approached me in the first place. He would explain our “us,” not through direct touch or communication but through artifacts, all those books and films, postcards and films, with “we” or “us” as the subject, as if there is any other. SL gave me those gifts—the movies and books and so on—because he knew, too, that I was like everyone else, except him: I identified with other people. His gifts were road maps to our love, the valley of the unconditional.

People looked at us and thought we were really evil.

As we became friends, the strangest thing happened: Most of our acquaintances abused adverbs in their rush to condemn—violently, passionately—our becoming a we. We were something dark and unforeseen: two colored gentlemen who moved through the largely white social world we inhabited in New York (the world where art and fashion and journalism converged) who did not exploit each other or our obvious physical traits—their coloredness and maleness—for political sympathy or social gain. People looked at us and thought we were really evil. That we had pointy heads and forked tongues. That we wore furs and had no animal rights. That we knew the twelve steps but skipped intimacy. That we betrayed every confidence and judged without impunity. That we lauded women and then denigrated them. That we mentored young boys only to corrupt them. That we borrowed money with no thought of returning it. That we were indolent and crackled with ambition. That we were gluttons who drank from a bottomless well of envy. That we were gay and couldn’t admit we were straight. That we were faithless Jesus freaks who had forsaken Him for tight pussy, credit cards we abused, and loose shoes. That we had lockjaw once but still managed to feed off our enemies. That we sold children down the river and watched them drown in an ocean of adult bitterness. That we were racists, especially against our own kind. That we were matricidal, especially toward our own mothers. That we were nothing like the “we,” or “just us,” in songs, lovely moments of togetherness we drowned out whenever we walked into a room, given our “loud” apparel, our conversation.

We faced these faces so many times: white women who had been denied nothing most of their lives feeling bitter about me and SL because they could not be part of “us,” but continuing to be attracted to us past the point of reason since they lived to be disappointed; white guys who wanted to fuck me for sport and who resented SL’s presence because he was perceived to be the embodiment of my conscience, which could not be defiled; black women who called us freaks since we somehow represented their twisted relationship to their own bodies and other black women; ambitious black male artists who resented our presence, largely because SL and I did not play by the rules they followed in their quest for success—a sad game James Baldwin describes in his 1961 essay “Alas, Poor Richard,” which concerns his intellectual twin or father, and occasional nemesis, novelist Richard Wright:

But we understood. No narrative preceded us.

The game Baldwin takes such pains to describe was a game our respective fathers had crushed our interest in early on, since they had tried to control us by applying its rules to everything we did in their effort to make us more like “men,” more like the men the world, white people, Jesus, our mothers, whoever, would not allow them to be. What SL and I intuited early on: Those rules were established by men who had nothing but contempt for colored people and women since they were so easily taken over and bought. We felt sympathy for those women who had wrapped their newborn babies in stock portfolios in direct imitation of their fathers’ values. We felt sad when all those Negroes couldn’t look us in the eye at parties. But we understood. No narrative preceded us. We were not “menchildren” in a promised land, as Claude Brown would have it. We did not consider ourselves as having “no name in the street,” as James Baldwin did himself. We did not suffer the existential crisis that afflicts some male Negro intellectuals, as Harold Cruse presumed. We did not have “hot” souls that needed to be put on ice, as Eldridge Cleaver might have said. We were not escapees from Langston Hughes’s “Simple” stories. We were nothing like Richard Wright’s Bigger Thomas, nor did we wear white masks, as Frantz Fanon might have deduced, incorrectly. We saw no point of reference in The Life and Loves of Mr. Jiveass Nigger, by Cecil Brown. We did not see the point of Sammy Davis Jr.’s need to be loved by not one but thousands, as detailed in his autobiography, Yes I Can. We were colored but not noirish enough to have been interesting to Iceberg Slim. We were not homies in the manner of John Edgar Wideman’s young proles floating around Homewood. We were not borne of anything Nathan McCall or Ishmael Reed, in his recent books, certainly, might deem worthy of talking about. In short, we were not your standard Negro story, or usual Negro story. We did not feel isolated because we were colored. We did not want to join the larger world through violence or manipulation. We were not interested in the sentimental tale that’s attached itself to the Negro male body by now: the embodiment of isolation. We had each other, another kind of story worth telling.

No one seemed to understand what we were talking about most of the time. There was no context for them to understand us, other than their fear and incomprehension in the presence of two colored men who were together and not lovers, not bums, not mad. Sometimes, as a joke, I’d wonder aloud to SL if we sounded like this to them: Ooogga booga. Wittgenstein. Mumbo jumbo oogga booga, too, Freud, Djuna Barnes, a hatchi! Mumbo lachiniki jumbo Ishmael Reed and Audrey Hepburn. And because the others couldn’t understand us, meaning was ascribed to us. We couldn’t be trusted. We should see a shrink. We should not spend so much time together; we were only hurting ourselves. We should spend more time in the art world, separately, so that SL could have more of a career as an artist. We should get on with our lives, separately, since there was no such thing as fidelity anymore.

I would be lying if I didn’t say these various opinions—or really one opinion—didn’t affect me: I’ve lived in New York long enough to know that any kind of failure is considered contagious. But something else overrode my fears: Once I was with SL, once we were a we, I wanted to house myself in SL’s thinking. It was so big and well lit, like a large house sitting solid on the bank of a river.

We tell each other stories in that house, largely unencumbered by the sound of other people’s fear, and for the most part that was true until our we began to disintegrate in 2007, a parting that killed the world for us. But that was later. Just now the world is whole. It’s 2000, and I’m forty, and I have a real home at last. I’ve dropped my bags at SL’s door. The house itself is composed of his skin and thought. Nearby, lilacs bloom in the garden door. Or are they hyacinths? “My mind forgets/The persons I have been along the way,” Borges said. And yet it’s those persons—in addition to my I—SL wants to hear about; he says they’re a part of who I was. Oh, Lord, don’t ever let this end: He smells like no one else on earth, and he sounds like no one else on earth. (SL’s voice is so deep that people often ask him to speak up, but he is always speaking up.) I love listening to what he says as I have loved listening to no one else talk. Once, after I’d written a piece SL enjoyed, he said: “Mama likes.” Once, while crossing a street in the East Village with a friend, she said, with a sigh: “Lord love a duck,” and SL added: “And other homilies.” Once, after a white girl insulted me about my weight, SL said of her: “I know how Daisy can lose seven pounds. Cut off her head.” And another time, when I described running into a white girl we both admired, SL, always starved for style, said: “Was she wearing anything at all?” About another person I longed to trust—I was always longing to trust someone; I was making life a fiction, or writing fiction. I longed for people to not be who they were, another thing SL forgives me for, and shall always forgive me for, even when he has to deal with the fallout, which is often, God bless him—SL said: “I’d trust her with about five dollars.” SL is a bullshit detector par excellence. His inability to fictionalize the truth—a habit I picked up from my mother, who was always hoping for a better day, she died hoping for a better day; I suspect SL doesn’t want me to die with similar hope flakes on my lips—is what makes me cleave to him, my protector, my truth.

I love listening to his stories. In his early, back-to-America days, SL hung out with some white lesbian separatists on a farm; there, he planted burdock, and ate cold griddle cakes, and read Our Bodies, Ourselves. It was the times. Everyone in his world was wearing plastic jellies except SL; his feet were too flat. One night, one of the girls approached SL; she wanted to be intimate with him; it would feel like part of his fabulous conversation. SL turned her down; she wanted to know why. They talked about it for hours, they processed and processed. The next day, SL left. He didn’t want to besmirch his utopia with his own presence. He repressed his heterosexuality to save women from it.

Standing above me and around me I see how we are all the same, that none of us are white women or black men; rather, we’re a series of mouths, and that every mouth needs filling: with something wet or dry, like love, or unfamiliar and savory, like love.

Once, in his house—a house of many embarrassing corridors that sometimes made one think something about a mother, I don’t know why—I asked SL what his life among the lesbians had been like. He said: “You mean women?” SL has a way of removing one category—lesbian—by getting at its root. It’s 2000 or something, and I’m on my way to SL’s. He has a studio in Chelsea; there, he photographs any number of women for queer magazines and the odd album cover. I love his pictures; they look like a cartographer trying to approximate a dream. Sitting on the subway, the lights go by but the people don’t. Standing above me and around me I see how we are all the same, that none of us are white women or black men; rather, we’re a series of mouths, and that every mouth needs filling: with something wet or dry, like love, or unfamiliar and savory, like love. And there’s my mouth, too, and it’s filled with SL, so to speak, including his idea that race doesn’t make much of a difference at all in his world of—aside from me—women.

But that’s not really true. It’s impossible to say whether or not the women SL has been involved with would have loved him as they did had he not been black, but I’d hazard a guess that probably not, just as SL had his type, too. In the words of one academic: There are no neutral narratives. Of course, all this contradicted SL’s everyman approach to life, its sidewalks and greasy diner countertops, just as SL’s object choices contradicted his tenderness. What SL’s women shared was this: They found other people’s misfortunes funny. SL and I did not find anyone’s misfortunes funny, but here comes another SL axiom: People do not sleep together because they’re similar. SL loved being an educator. He was hilarious and sage. Once he said about a number of women he knew: They’re fucking multi-orgasmic, but what really gets them off is a cheap rent. His gargantuan patience had an enormous influence on any number of young women who lacked home training, and who leaned mightily on attitude to get them by. This was interesting to me: SL’s lovers had, in abundance, the very things he wanted to tame, which was the stuff he was attracted to in the movie stars he loved most, too. SL on Bette Davis: “ugly and with attitude? Fabulous.” SL on Elizabeth Taylor: “I love her in almost any movie. It’s like she’s always saying, ‘Are you too fucking stupid to understand what I’m saying?’” He also loved Janet Shaw, who played the laconic, don’t-carish waitress in the sleazy bar in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1943 film Shadow of a Doubt and anything featuring Grace Zabriskie. In fact, one of SL’s early video pieces featured images of Zabriskie taken from Gus Van Sant’s fabulous 1991 film My Own Private Idaho. In the clip SL used, Zabriskie stands in a room looking over a trick (River Phoenix) with a cold, appraising eye. She walks around Phoenix slowly and, as she does so, she pulls her robe closer about her. Overwhelmed by the presence of this woman—and the memory of the first woman: his mother—Phoenix collapses. What boy doesn’t understand that moment? And it’s part of SL’s genius that he doesn’t know where those moments come from in his work, just as he doesn’t understand why he’s attracted to women he wants to school when they will not be schooled.

Then she complains to the management: Isn’t it a shame a lady can’t feel safe eating out on her own?

In 1999 or so, SL’s mother came to visit her son. She lived in a small town in the Midwest. Mrs. SL was handsome and small; she looked the way the director Robert Wilson described his mother in an interview: “My mother was a beautiful, intelligent, cold, and distant woman…She sat beautifully in chairs.” Sitting with the beautiful Mrs. SL in a restaurant, one was reminded that one of SL’s favorite movie scenes involving a mother occurred in The Grifters. In that 1990 film, Anjelica Huston plays a mother and con artist who loves her only son, but not at the expense of herself. The scene that amused SL most in that film takes place in a diner. Huston lays a fresh dude out by cuffing him in the throat. Then she complains to the management: Isn’t it a shame a lady can’t feel safe eating out on her own?

SL’s mother looked at me across the dinner table with don’t-care-ish-was-I-stupid-I’m-pulling-on-my-Grace-Zabriskie-robe attitudinal eyes. But we had another dinner together, and she saw how much her son loved me, and she did what most women do in similar situations: She adapted. I was her best friend until she didn’t need me to be her best friend. And in a bid to be included in what turned her on, which is to say what she perceived as a boys’ club—she didn’t have much truck with women—Mrs. SL pretended to understand what we were talking about, but I know she didn’t. How could she? How could any girl? We were better mothers than any of them.

It’s a measure of SL’s difference in most ways that he didn’t fuck me up after I expressed—silently and sometimes not so silently—my occasional reservations about his family. (Typically, he was more concerned with what he called my “terrible need to confess,” as opposed to what I expressed.) Most colored men can’t deal with anyone talking about their mama. But it was a measure of SL’s trust in me—and his interest in the philosophy of language; why take it personally when you didn’t have to?—that allowed for those moments when I felt out of control because people of color were out of control toward me. The issue of racial loyalty is a tricky one, and largely specious if you knew the colored people we knew. Vis-à-vis that whole endlessly fascinating and tiresome race subject, SL and I lived as the actor Morgan Freeman said he lived: He didn’t play black, he was black. And it broke SL’s heart when I assumed fraternity with other black writers because, for the most part, they could care less what I felt. What interested them was how much of the black pie would I get. Or take away from them. Literature was a market. For instance: A black gay woman I was friends with at the weekly newspaper where SL and I met had a brother who was dying of AIDS. In fact, they had the same name. I used to go to one hospital to cut her brother’s hair, and then to my friend’s hospital, so he could kiss me good night. Both those young men died, and it was some months later, to win her white straight male boss’s approval, that that black gay woman took me out to lunch to ask if I would give my health insurance up—someone else needed it. SL liked to die as he watched me try to fill that dry fallacy of brotherhood with the Botox of faith. He turned his face away as those people behaved badly toward me because they could: They saw that I believed in them because I felt I should.

Once, at a party, when I felt he was ignoring me, I threw chairs at him.

Of course, when things turned bad, SL was the beneficiary of my angry sadness. Once, at a party, when I felt he was ignoring me, I threw chairs at him. I, too, could be unschooled. But I could not do what I saw white women do to him, which included everything I did to him. I belittled him because, upon occasion, his empathy and stoicism annoyed me even as it turned me on; I complained about him to other people—white women mostly—because I just knew he didn’t love me, and wasn’t it always going to be about some other bitch, but when I had lunch with a white girl who knew us both, and she compared SL to her ne’er-do-well black lover, I said, SL doesn’t hurt people like that, even when they want it, and I never really spoke to her again. And where was the love I wanted to scream as SL held my hand through my mother’s death in 1993, and where was the love and when will I see you again I wanted to plead as SL held my hand and heart up in Barbados two years later, it’ll always be one of the sadder islands to me because my mother died there, and, while SL and I traveled around visiting several of her relatives, trying to feel what she must have felt in her ancestral home, her relatives expressed a dry lack of concern over the fact she’d gone home to die, I think that was important to her, but where was the love, stand by me, I wanted to sputter when I felt as though I would collapse between the army of words I had to produce in exchange for shelter, and the army of words I wanted to produce in exchange for myself. And where was the love, when will I see you again, I belong to you, I hissed through gritted teeth even as SL read our book of days—smiling.

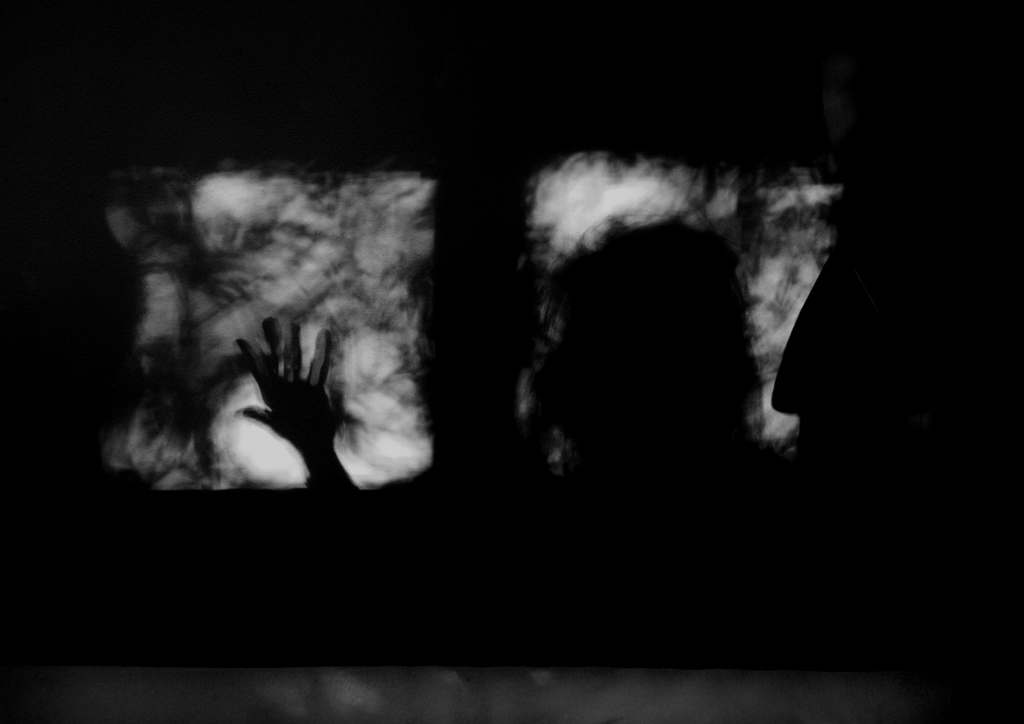

In SL’s house there are many mirrors. We don’t get in their way. What would be the point? Our eyes are monstrous and loving enough. “My mind forgets/the persons I have been along the way.” And yet SL wants to know each and every one of those persons who had gone into the making of my me. How dare he stand there waiting for my I of selves? No one can have them, or me. But he counters with: How can we be a we, if I don’t know your I? Edna St. Vincent put my rejoinder best: “Why do you follow me?—/Any moment I can be/Nothing but a laurel tree.” Still, SL’s love wanted every bit of me while I ate secrets in order to formulate a self; those selves were more interesting to me than my I. No one else can have those selves. Or me, who’s not nearly as interesting as those other stories—about Marlene in her white dress standing near a tree, or one of my sisters walking into a room and changing everything. How dare SL stand there waiting for my I. Is this what loves gets up to, one person demanding self-exposure so there’s more to love, a feeling best described as the devil eating you alive, from the toes up? About that toe. In SL’s house, I read Vladmir Nabokov’s novel Despair (1936). In that book, a Russian émigré businessman named Hermann Karlovich meets his doppelgänger—a German word I’ve just learned means “double goer.” (The French words for “pairs,” or “some pairs,” is des paires. Marvelous.) Despair doesn’t tell much of a story—I should talk if my I did talk—but at the heart of the book is the story of love. Hermann is always looking for it, and it’s always out of reach because he’s looking for it, like any number of us. His first double is his brother. Hermann recalls talking to his shallow wife, Lydia:

And if I were not SL’s younger brother, what was I? I could not bear to be alone knowing he was in the room. I sucked his figurative toe because its sweat acted as a kind of poultice on my tongue; I would say who I was if he would not take it away from me, that sandy-colored digit, as stimulating as anything, curling up at the tip as his flat foot tapped the day away as he waited for me as he stood in his house, braver than any memory.

In his house, we tell each other stories largely unencumbered by the sound of other people’s fear that surrounds us in New York. Or so we wanted to believe. Upon moving in, our neighbors phoned the police. It must have looked strange: two colored gentlemen moving furniture into a house. As a result, we become more isolated. Our isolation—like all isolation—breeds a certain amount of discontent, and it takes the form of questions about who we are, as twins and not. Twinship, SL says, is the archetype for closeness; it is also the archetype for difference: In one’s other half, one sees both who one is and who one isn’t. Here we are on Wuthering Heights. Our neighbors eat bitter black bread and look bitter when they see us coming. The rain falls. The birds fall in the rain.

Most days, or most nights in SL’s house, it is I who asks SL to tell me a movie story. He loves movies so, maybe he’ll love me so. But why is it that when he tells a movie story, or any kind of story at all, he tells it from the point of view of the eye and heart that is following the white girl in the tale? Does he identify with them? Feel “like” them next to my not–Liz Taylor skin and crinkly pubes? How can I change his mind—get him to see me—when, like the rest of us, he is a slave in relation to his overbearing past, shackled to these memories that he has not shared with me but I know just the same because we’re twins: young white girls rolling their stockings down on a beach in Corsica, near the Bosphorous, and SL, shunned because of his color or being profoundly without family, sitting nearby, barely aware of his body, other than his eyes, which are filled with such longing. They’re the same eyes that find such pathos whenever Laura Nyro sat down at the piano, or humor and concern when Sigourney Weaver fought off aliens, especially in suburban Connecticut, or familiarity when Nico stood flickering in an Andy Warhol film, disassociated from and connected to her child as she cut her bangs, later to amuse SL ruefully, when Nico delivered her rendition of “Deutschland Über Alles,” in her own way, what a strange song for a colored boy to know by heart. In Europe, SL became a white woman. He felt no separation between himself and the women rolling their stockings down. When I knew him, we both stopped dead in our tracks when we saw the Benetton ad that showed an albino African girl standing in a group with black Africans who didn’t have that issue. SL identified with that ad for his reasons, and I identified with it for my own.

Like the books and photographs he shares with me, the parts of the movie stories he tells make indirect reference to us, and our story, and then the whole world is not otherwise.

SL would sometimes leave me alone in his house when he had to work, that is, deal with freelance graphic-design jobs. When he returns after a day or two, he usually brings a gift—photographs, a book—that’s very much in keeping with the generosity he exhibited when we met fifteen or twenty years ago. He also brings stories. About one new movie, or the next. Like the books and photographs he shares with me, the parts of the movie stories he tells make indirect reference to us, and our story, and then the whole world is not otherwise.

But around 2006 SL became less available to the telling. For several years before that I could feel him becoming an I. And like a photographic negative in reverse, I watched as he began to fade away from our image bit by bit. He’d spend less time listening to me laugh while standing under a door frame smoking a cigarette in the rain; he became less present to the anxiety I have around writing; he wouldn’t touch those hyacinths for days. The truth is what I imagine: He’s met a woman who would benefit from his touch. That same woman will be welcoming to me socially. She will look on my friendship with SL with great admiration. She will be pale-skinned and blush, charmingly, when I make some not-at-all-veiled reference to how loving and difficult SL can be, a shared joke of love. She will have worked with SL on some project, maybe she’s an art director, or a stylist, that’s how they met. She will have noticed SL for a while before he began giving her books and photographs. She will phone me, not exactly with SL’s permission, but he will not resist our going around together, this is his dream of love, me and a woman loving him, and our loving each other, and that will happen for a little while, but then she will become annoyed by the way I can make SL laugh, and she will eventually be vexed by my ability to listen to her everlasting love for him, and how that love has created a hole in her heart, why does he need other people, wasn’t she enough, the implication being that I was other people, another “we” altogether, a foreign body that was something less and something more than her white body, which would not see as such, in any case, only the shape of her wounded love. She will wonder, before long, what he sees in me. She will make scenes on any public occasion that I host—a birthday party, say—because that means she’s passionate about him. She will hire me to do some freelance work for her, but that has nothing to do with what I can or cannot do; it’s just an opportunity for her to tell me what to do, to criticize my work and denigrate me in the process, because it’s one way to attach my we with SL. But he will go home with her, despite or because of her movie drama. He will kneel and wash her feet despite or because of her movie bloodletting. He will try to open her flesh by beating at the door of it with his flesh, just like the movie guy who kisses the movie girl. And he will be all in love because he’s done this before, with any number of white girls. But the difference in 2012 is, I’m not central to it.

In all those years in the house I used to wonder: If a man touched me in the way that I imagined SL touched white women, would I die? A friend told me once that his first brush with intimacy during the height of the dying epoch was with an older man who would rub my friend’s facial cheek with his own while saying, I like you. No kissing. I like you. No close hearts. I like you. No grabbing. I like you. No shared saliva. I like you. That was the way it was not just for my friend, but for so many people, including myself: love not fully expressed physically wasn’t true love; they wouldn’t die if you didn’t touch them. Before, I touched SL through white girls. And I got him back, always, because I offered what they could not: love that was free of their quest for “liberation,” and thus egoless. Or so it seemed. After a few months away in that world of women, SL would come back to our play, and the cast of characters in our village, the backdrop of sea spray. But by 2006, neither of us verbalized what we felt: my I, and his you, and the ever-widening gulf in our twinship. Look at that empty door frame, look at that unhappy hyacinth. But I cannot look at the days SL spends away as those days. That is, I cannot see them for what they are, and what I am now: unjoined, without pattern, some meaning, a series of questions, untwinned. I cannot look at myself as myself and not see him, or the feeling of him, not SL, but the first we, and feel our unjoining because of death, but he couldn’t help it and SL can, he couldn’t help his jawline becoming sharper above the checked shirt that was disappearing him, I didn’t want to look, I couldn’t help it.

How could I compete and keep him near me forever? By becoming a white girl, too? And what kind?

But SL wasn’t dead. He was with a white woman. How could I compete and keep him near me forever? By becoming a white girl, too? And what kind? One white girl we loved: Adèle Hugo. We so loved Isabelle Adjani’s portrayal of her in François Truffaut’s 1975 film The Story of Adele H. Born in 1830, Adèle was the youngest daughter of Adèle and Victor Hugo. Hugo’s other daughter, and his favorite of the two, was named Léopoldine; she was Adèle’s elder by some six years. (The Hugos also had three boys, one of whom, Leopold, died in infancy.) In 1843, when Léopoldine was boating on the Seine in Villequier with her new husband, Charles Vacquerie, the couple’s boat capsized, and they were drowned. Victor Hugo mourned his daughter’s loss for the rest of his life; in fact, as a result of that loss, he became interested in the occult, séances and the like: He wanted to contact Léopoldine in the beyond, often consulting with Madame Delphine de Girardin, Hugo’s “spiritist.” Adèle would follow suit, eventually believing that Léopoldine was a kind of twin; the young girl would sit at the “table” in whatever room or house she lived in and call on her dead sister’s spirit. Adèle could love the dead because of what they meant to her imagination. How did I love my dead? Did my love for them cut me off from the living? Adèle could not love her fiancé because he was not absent enough. Was I the same with SL? In her famous diary, Adèle wrote about her fiancé:

I, you, me, us, words let alone concepts I struggled with as well. Did SL have his own we? Was I his Auguste, or was he mine? In the midst of her rejecting Auguste in favor of the unattainable, Adèle Hugo wrote:

I did not kiss SL but that which was not my body—my spirit—did. Did he feel it? Did my kissing help continue to make our love? Would my kissing make the love that would make him stay? I was Adèle. But before I could manage that transformation—would I end up as she did? Living for a time in Barbados, searching for a love she could not see when it passed her on the street because it was so solidly in her imagination what did reality have to do with it? So tristes, so tristes—SL and I had many years of unrealized kisses folded into conversation.

In our home that is his body I said something like this once: I have always thought of twinship, by birth or choice, as a kind of marriage: Another metaphor that sustains some of us. And as metaphors go, marriage—twins joined by a ring and flesh—has always been attractive to me, the pomp and circumstance, the illusion veil and orange blossom, the rice landing on sanctioned heads like a hard rain as I and I become we, if they weren’t born that way.

I need an audience to tell me how my love story is playing.

Call me what you like, but I cannot marry myself; there is no story there. If I lift my illusion veil—but just for a moment—and put away the songs I’ve planned to play at my nuptials, songs such as the Talking Heads’ “Thank You for Sending Me an Angel” (“Baby you can walk, you can talk just like me”) and Hole’s “She Walks on Me” (“We look the same! We talk the same! We are the same! We are the same!”)—if I stop all that, I can see that any such celebration is completely driven by my writerly self, like so many things. I need an audience to tell me how my love story is playing.

SL abhors weddings, all that “O thou to whom from whom, without whom nothing,” stuff Marianne Moore eviscerates in her great poem “Marriage.” SL is bemused by all the conventions I cling to, like dopey trimmings on a Christmas tree. What SL believes: No wedding ring can cast a golden light on anyone’s we. No we is without friction. The exchange that takes place between I and thou is essentially private—like the intuitive language of twins. Like the vivid language marriage-crazy Nijinsky employs in his 1919 Diary to describe life with his first wife, his first twin, the ballet impresario Diaghilev:

Like dancers, none of us gets over that figure we see in the practice mirror: ourselves. Choosing your twin gives you that reflection forever—or as long as it lasts. Perhaps SL will leave me for one reason or another, but he will never go away: I see myself in him and he in me, except that for him our twinship is essentially private and silent. So how do I justify putting our we-ness out in the world by writing about it? I can’t. It’s something I’ve always done; SL accepts this in me: half living life so I can get down to really living it by writing about it. I wrote about my first kiss more fully than I lived it. I wouldn’t know what I looked like in relation to SL, my twin, if I didn’t describe it on the page.

It’s 2002, and we’re twenty years into our twinship. Little has changed, except for our age. We’re both over forty. Our bodies remain what they always were. SL is thin and I am not. I tried to grow a great beard like his. It didn’t happen. Not that I know what I look like at all—with or without a twin. Over the years we’ve shared, I have tried to see myself, the better to see him. To that end, SL made a gift of the novel Immortality, by Milan Kundera (1990). In it, I read: “Without the faith that our face expresses ourselves, without that basic illusion, that archillusion, we cannot live, or at least we cannot take life seriously.” In a way, that basic illusion is beyond me. I wrote the following on the corridor walls leading to SL’s great room to describe that feeling:

I have always been one half of a whole. The first Hilton was stillborn. His little wet head and arms and feet were dragged out of a mother who did not want him. That mother was my mother’s closest friend. She told my mother, during her pregnancy, that if her child turned out to be male, she wanted him dead, given how despicable she thought men were, especially her husband. So she willed Hilton’s death. She had named her child Hilton—a boy’s name—even before he was born. Perhaps she’s always wanted a boy to kill.

A year or two after that, my mother gave birth to Hilton again: myself. My mother named me Hilton for her friend’s stillborn baby. The minute I was born, I was not just myself, but the memory of someone else. And I belonged to two women who identified with one another for any number of reasons, my mother and her friend, the one who bore death and the one who bore the rest. As boys, we went everywhere together, Hilton and I, my ghostly twin, my nearly perfect other half. He was perfect because he never seemed to need anything, even though we grew up in the same family.

We lived in Brooklyn then, in a two-story house in East New York. It was a place of spindly trees. We had four older sisters who dressed like the Pointer Sisters on the cover of their debut album. We knew we’d never get over them, or our younger brother, whom we adored. And our Ma, who raised us all. We never knew what any of those people were talking about when they used I as a pronoun—they were all the same. They were annoyed by anything they perceived as the catalyst for separation. Evil forces from the outside world included: boyfriends, anyone else at all. (They didn’t know I had a twin. They would have resented him.)

Our Ma. We were all the same to her. We were her we, a mass of need always in need of feeding. Our Ma. We were all the same to her. We were her we, a mass of need always in need of feeding. Standing over a pot of boiling some- thing, waiting for what she called “the last straggler” to straggle in to dinner—our brother Derrick, say—she would call out each of her children’s names, as if naming off all the parts on one body: “Sandra! Diana! Louise! Yvonne! Hilton! Derrick!”—before giving up and giggling and saying, “Whoever you are, whoever I’m calling, come in and eat.”

I was fat and drank so much soda and Kool-Aid, you wouldn’t believe it. By the time I was thirteen, I had enough fat to make one thin perfect Hilton, so I did. I was the stronger twin. I was a little smug because I had a twin, not unlike Ramona, the smart glutton who invents a thin twin for herself in Jean Stafford’s brilliant 1950 short story “The Echo and the Nemesis.” At the end of the story, after Ramona’s been found out as the mythomaniac and hoarder of food she is by her classmate Sue, Ramona still feels she has reason to gloat. Glittering with malice, she tells Sue she will “never know the divine joy of being twins,” and ends by calling Sue “provincial one.” Sue is a “one” and Ramona is not and a double is more, in every way. Exactly. Exactly. For Hilton and me, knowing each other made us feel exalted. Everyone else was a plebe. We knew so much about so many things! We read about identical twins, two beings split in one egg. We looked at pictures of twins by marriage—our favorite being Eleanor and Franklin Roosevelt. We loved pictures of them by the sea, standing close together, split from the same romantic egg, one pretty, one not so pretty. We looked at art books, at the work of Gilbert and George. We read astrology books. We knew how to look at clothes. We knew how to write short stories.

At the end of our thirteenth year, there were many changes outside our control. We moved to an apartment in Crown Heights, among other West Indians who called themselves a we, one political body, proud of their association by birth with former Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm. By the time we moved into that apartment, a lot of our sisters had moved into their own homes. Another change was Hilton and I went to a predominately white high school in “the city.” It was the first time we had ever been around white people much, so it was strange to consider our own bodies next to theirs and it made us hate each other for the first time—Hilton and I. If only we could be rid of one another, we would be the one that another one could love. But since there was two of us, there was two of everything no one seemed to want, including, or specifically, our coloredness, our double lovesickness. How strange we must have looked, walking down the street! Like thieves in wait for someone to give up something we could not demand, because we could not speak. Our demand for love felt cruel, even to ourselves; to speak it would be a crime.

We couldn’t stand in front of those buildings for long without being glared at by those doormen, so we had to imagine the person we had a crush on, on the long subway ride home, to Brooklyn. We followed the white people we liked home. They lived, most of them, in tall apartment buildings with doormen. We couldn’t stand in front of those buildings for long without being glared at by those doormen, so we had to imagine the person we had a crush on, on the long subway ride home, to Brooklyn. We imagined them going up to their beautiful home in an elevator and going into their bedroom (their own bedroom!) and turning on their desk light and putting on a record by some singer we had overheard them talk about in the school cafeteria (Bob Dylan, Van Morrison), and then taking off their jeans, their leg hair lying flat on their legs like stockings. Our imaginings split us up—Hilton and I. We wanted to be a we with one or another of the people we followed home, so we split up to make room for those other people, who were never coming and sometimes there and whom we always partially imagined. And in this way, years passed, until I met SL and became a we with someone entirely different.

Excerpted from White Girls by Hilton Als. Copyright © 2013 by Hilton Als. To be published on November 12, 2013 by McSweeney’s. Reprinted with permission.