S

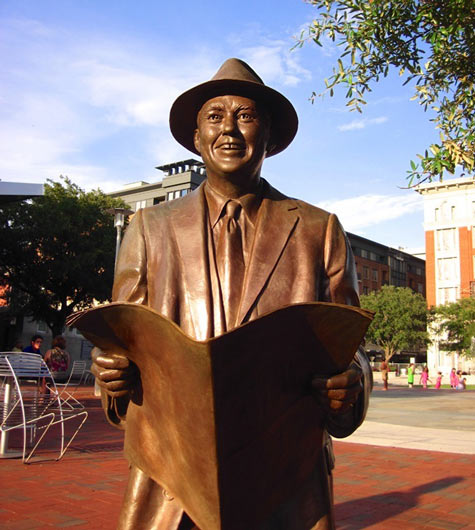

avannah native Johnny Mercer—the successful entertainer, co-founder of Capitol Records, and writer of jazz-interpenetrated popular song—once defined the world as stretching “From Natchez to Mobile / From Memphis to Saint Joe / Wherever the four winds blow.” His hit “Blues in the Night” delineated an imperfect geographical South on the larger globe, but listeners understood he meant a specific region long recognized as different. Mercer trafficked in the sui generis jazz, blues, and hillbilly sounds that he and other Southern diaspora entertainers took with them when escaping the drudgery of sharecropping cotton and its retainers for the brighter lights of northern and western cities.

Music offers just another reflection of the cultural hybridity of the South’s multiracial population. From the moment Europeans mixed with Native Americans at Jamestown, then brought Africans into Virginia and Carolina, the distinctive South emerged with its Creole culture, never to disappear despite the atrocities of slavery and segregation. The persistence of the plantation with its coerced labor force and cash-crop economy created a sense of place shared by white and black, who joined the Native Americans in a love of the land. That earth produced the region’s famous cuisine that John T. Edge and the Southern Foodways Alliance documents, its whole a subtle mix of its global parts as in a gumbo with its varying ingredients of African okra, American file, and European roux. For centuries such multicultural expressions remained accessible only in the South but by the time Alabamian Hank Williams, Jr., started singing about “Jambalaya, a-crawfish pie and-a file gumbo,” the region had reintegrated into the nation thanks to the collapse of the plantation system with the Great Depression and the economic incentives of World War II.

Southern writers recognized the transformation taking place, capturing the dying South in works of fiction by William Faulkner, Jean Toomer, Zora Neal Hurston, and Flannery O’Connor. Songwriters realized it, too. New Orleans’s own Dr. John—who recorded an album of covers called Mercernary—noted about the line “My huckleberry friend” in Johnny Mercer’s most famous “Moon River”: “No body but some body from the South would say something like that.” Indeed, the man who penned “Pardon My Southern Accent” and wrote such lyrics as “I jumped out of the frying pan / Right into the fire” for Baltimore’s Billie Holiday to sing, and “Take my word, the mockingbird’ll / Sing the saddest kind of song” for Nashville’s Dinah Shore to sing, and “I miss you most of all, my darling / When autumn leaves start to fall” for Montgomery’s Nat “King” Cole to sing—that songwriter, Johnny Mercer, could speak for all Southerners when talking about home.