In 1965, Srila Prabhupada, a 69-year-old holy man from India, sailed to America with a decades-old assignment from his spiritual mentor: to spread an ancient strain of Hinduism to the Western world. Arriving in New York’s Lower East Side at the height of the sixties—a time ripe with disenchantment and hippie experimentation—Prabhupada found fertile ground for his worship of Lord Krishna, characterized by a particular chant. He set up a storefront temple on 2nd Avenue, began hosting ceremonies in Tompkins Square Park, and within a year, officially founded ISKCON, the International Society for Krishna Consciousness—what has come to be known as the Hare Krishna movement.

The Hare Krishna mantra—“Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna, Krishna Krishna, Hare Hare…”—would soon be heard across the country, thanks in no small part to endorsements from the era’s greatest cultural icons. Allen Ginsberg, a regular at Prabhupada’s evening chanting sessions in Manhattan, quickly became a national spokesperson for the religion. The mantra “brings a state of ecstasy,” and had replaced LSD and other drugs for many devotees, Ginsberg told the New York Times in 1966. At the famous Mantra-Rock Dance in 1967, The Grateful Dead, Janis Joplin, and Jefferson Airplane appeared with Prabhupada at the Avalon Ballroom in San Francisco, chanting the mantra with thousands of fans. In 1969, Hare Krishna devotees performed with John Lennon and Yoko Ono on “Give Peace a Chance,” and the following year, the mantra was prominent in George Harrison’s international hit “My Sweet Lord.”

But what began in the US as the religion of the counterculture has shifted dramatically. In the 1980s and 1990s, with the loss of many of their early hippie followers, ISKCON communities experienced significant decline and, subsequently, reorientation. As Indian immigration to the US increased, the religion sought to identify itself with Indian Hindus and provide them with a place of worship. Estimates suggest that today, in major immigrant hubs such as Dallas, Atlanta, New York, and Chicago, approximately 80 percent of ISKCON congregants are of Indian origin.

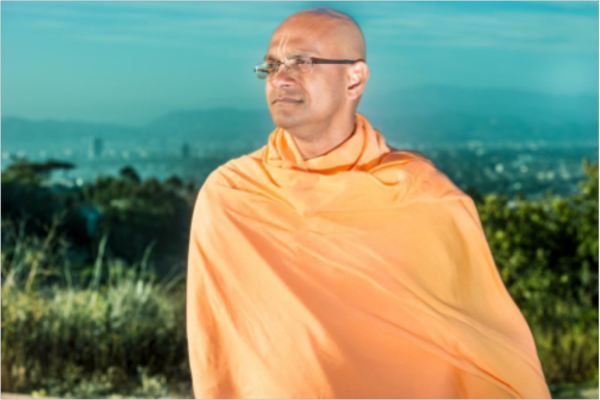

Gadadhara Pandit Dasa is a monk at the Bhakti Center, an ISKCON temple and educational space in lower Manhattan, just blocks away from Prabhupada’s original storefront temple. As he recounts in his memoir, Urban Monk: Exploring Karma, Consciousness, and the Divine (2013), Pandit spent his early childhood in India, and in 1980 immigrated with his parents to Los Angeles. However, his family’s livelihood was soon upset by a fire that destroyed their business, and they moved to Bulgaria to pursue opportunities in the newly free-market country. There, Pandit came across a copy of the Bhagavad Gita, one of Hinduism’s central scriptures, which, at that uncertain moment in his life, he writes, “pierced me to the core of my soul.”

Upon his family’s return to the US, this time to New Jersey, Pandit took a job selling mortgage loans to people in desperate financial circumstances, work he describes as “toxic,” but continued to find existential uplift in the Bhagavad Gita. His copy of the text happened to be published by an ISKCON press, so he sought out the affiliated temples in New York City. Soon a regular visitor, Pandit developed friendships with the monks there, and signed up for a temple-led trip to India. What was intended to be a one-month retreat at a monastery lasted for six months, and when he came back, he felt compelled to move right into the monastery in Manhattan.

Fifteen years have since gone by. Each day, Pandit rises at 5 a.m. for a morning ceremony of chanting, meditation, and spiritual offerings. Later, he might prepare food for his fellow monks, or read the Bhagavad Gita with visitors. But while Pandit’s lifestyle is governed by monastic standards—among them, celibacy and strict vegetarianism—he is far from hermitic. He lectures regularly at colleges and schools, conducts meditation workshops, teaches vegetarian cooking classes, and has served as Hindu chaplain at Columbia University and New York University.

I visited Pandit at the Bhakti Center on a drizzly evening in mid-November. We spoke inside the temple, a compact space that, with its warm, dim lighting, polished floors, and subtle finishes, felt more like a well-appointed living room than a religious institution. A single altar holds doll-like figurines of Krishna and his lover, Radha. The walls are lined with sumptuous paintings of the couple, and on one side of the room is a life-sized, disarmingly realistic sculpture of ISKCON founder Prabhupada, seated cross-legged in meditation. Against the thrum of rain and occasional wail of sirens, Pandit and I spoke about how the Hare Krishna movement took hold in the United States, food as a religious teaching tool, and how urban life informs his sensibilities as a monk.

—Meara Sharma for Guernica

Guernica: For many, the words “Hare Krishna” conjure images of white hippie devotees, dancing and singing in city parks and doling out food and books to passersby. I’m curious to hear how this stereotype came about. Can you talk about how the Hare Krishna movement took hold in the United States?

Gadadhara Pandit Dasa: Srila Prabhupada’s teacher, in 1922, had asked him to take his message of bhakti, devotion to god, to the Western world. It took Prabhupada forty years to execute that instruction. In 1965 he was sixty-nine years old. He came over alone—he had no disciples, here or in India. From what I understand, nobody saw him off when he left from Bombay, and there was nobody waiting for him when he arrived at the dock in New York. It took more than thirty days on the ship; he had two heart attacks on board. In his diaries he says that when he arrived, he didn’t know whether to turn left or right. Ultimately he came to Manhattan, where he lived in different people’s homes because he had no money.

He eventually settled in the Lower East Side. Imagine, this elderly Indian man wearing saffron robes, walking around New York City. That’s important to understand—it wasn’t started by some American guy, some counterculture American dude. This was a Bengali man. He’d go to Tompkins Square Park, Washington Square Park, and he’d have Bhagavad Gita discussions at a storefront just a block away from where we are now.

This was the center of the counterculture back then. People were disgusted by the way things were working in America, rebelling against the Vietnam War, rebelling against American politics, rebelling against American culture and religion. They were all looking for something different—so Eastern philosophy resonated with them.

Guernica: Did American cultural values of that time come to influence the religion?

Gadadhara Pandit Dasa: I do know that when Srila Prabhupada came here and saw American culture, he made a few changes that were somewhat controversial in India. He saw that men and women related very equally here, so he allowed women to become priests. And he’d create monasteries for both men and women. I don’t think that had ever been done in Hinduism. That was pretty revolutionary, to come over from a highly traditional culture and have the vision to make those changes. Even in India now, I don’t think women tend to go to the altars. The culture wouldn’t be fully accepting of it.

But he didn’t make any changes to the philosophy just to suit the Western audiences. He made external shifts, but nothing from the texts changed just to appeal to Americans. I appreciate that—he remained authentic to the tradition, and those who were okay with all of that came to him.

Guernica: Since the 1960s, when, as you mentioned, Hare Krishna followers tended to be white counterculture folks, there’s been quite a demographic shift.

Gadadhara Pandit Dasa: We have to understand that at that time, there just weren’t a lot of Indians in this country. Indians basically started coming in the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s. Had there been more Indians then, they would have naturally gravitated toward the temples Prabhupada established around the country. In the years between when he came here and when he died, 1965 to 1977, he established 108 temples across the world. But because there weren’t many Indians to be found in these places, they were filled with Westerners.

At that time, the tradition was kind of confusing for the Indians who were here. Some would say, “Look at all these Western people practicing our tradition, it’s amazing.” Others would question why there were white men in saffron-colored bedsheets and white women wearing saris. When I walked through the doors, and saw Western people practicing, I thought, “This is incredible, these people know the Bhagavad Gita better than I do.”

But if you go to most ISKCON temples now, you will find something like 80 percent of the congregation are Indians. If we had a huge population of Indians when Prabhupada came over, we would have seen a very different dynamic.

Guernica: What are the core beliefs of the Hare Krishna movement, and how does it differ from traditional Hinduism?

Gadadhara Pandit Dasa: The idea, as in conventional Hinduism, is to develop a love of god. Our main spiritual text is also the Bhagavad Gita. And like conventional Hinduism, you have images of god on the altar, and you worship them. But in the traditional Hindu temple, you’ll see fifteen or twenty deities. You walk into a Hare Krishna temple and you’re going to see Krishna and Radha [Krishna’s lover].

We are exclusive worshippers of Krishna. We are monotheistic. We don’t deny the existence of all the other gods; we understand they are powerful beings that should be respected. But ultimately there’s one Supreme Being for all traditions and that’s the person who should really get our worship.

That is not some concoction. Most of our scriptures say there’s one Supreme Being maintaining all the others. Krishna says, “Everything rests on me as pearls rest on a thread. I am the creator, maintainer, and destroyer of everything. From me comes knowledge, remembrance, and forgetfulness. I am the heat and light of the sun and the moon. I am the ability in human beings. I am the strength of the strong. The intelligence of the intelligent.” If you study the different texts of Hinduism, it becomes loud and clear that Hinduism is actually monotheistic. There are many gods, but they’re seen as managers of the universe. They’re not the Supreme Being.

If you have somebody coming to you only when they need help, how likely is it for you to return their text message?

Guernica: Saying Hinduism is not a polytheistic religion is quite a controversial statement, I imagine.

Gadadhara Pandit Dasa: It can be, for those who are uninformed. Maybe we need a different definition. But I work with Hindu students a lot, at Columbia and elsewhere, and I ask them, “How many of you think it’s monotheistic and how many polytheistic?” Half will say it’s monotheistic. They’re becoming more and more informed.

A lot of times in Hinduism, people worship these gods with a motive. Ganesh, remove my obstacles. Lakshmi is associated with money. Saraswati, the goddess of knowledge, pray to her before a test. There’s nothing wrong with that—at least some higher form of divinity is being worshipped. But in our tradition, bhakti—love for god—is without any motivation. If you have somebody coming to you only when they need help, how likely is it for you to return their text message? Love of god should be unmotivated. When I pray, when I meditate, all I should ask Krishna is to help me develop love for him. Please purify my heart of any anger, greed, or pride, so I can fully love you and all of your creation. It’s the only thing I should be asking for.

Guernica: How do you contend with the stereotypes about Hare Krishnas?

Gadadhara Pandit Dasa: They don’t really bother me because I know they’re coming from a lack of knowledge. And also the way we have portrayed ourselves. Being out there, all over the streets in the ’60s and ’70s, chanting in public, being in airports. But one great thing about all of that is people know who we are. And all sorts of people walk through our doors, which is fantastic. You go to any other Hindu temple in America, you’re pretty much only going to see Indians. We feel proud of the fact that we’ve made our tradition accessible to Indians and non-Indians alike. That’s what Srila Prabhupada wanted.

Guernica: I grew up going to a very traditional South Indian temple in Massachusetts. There were dozens of deities and simultaneous pujas, you’d sit on an austere concrete floor, there was a somewhat dingy basement where you’d eat temple-prepared food on Styrofoam plates. That’s the temple aesthetic I’ve experienced all over the US, as well as in India. Some Hindus might find this place doesn’t feel like a temple.

Gadadhara Pandit Dasa: If somebody’s dependent on a hard stone floor for their religious feeling, if someone stacks that much on the external, I think there’s already something wrong there. When it comes to our worship here, it’s as traditional as any other temple. We have offerings for Krishna five times a day. We change Krishna’s clothing in the morning and evening. That’s our balance, to keep the full tradition alive while simultaneously making it accessible. Most other temples, you won’t find that. What I hear from a lot of Hindu youth is, “We can’t relate to that priest in our temple.” But they can relate to me—I grew up here, I speak their language, but I’m also a priest.

Being a monk was not on the list of things to do when I was growing up in Southern California, going to the beach every weekend.

Guernica: How did you become a monk?

Gadadhara Pandit Dasa: My search began when my parents lost their multimillion-dollar jewelry business in Los Angeles. I first started reading the Bhagavad Gita when we moved to Bulgaria for a business venture. The Gita I was reading happened to be a Gita from ISKCON. It was incredible how easily I was able to understand the philosophy. The questions and answers were just so clear-cut.

So ultimately, when I came to the East Coast, the logical thing was to go to the temple where these books were coming from. I went to the New Jersey ISKCON temple, the Brooklyn temple, and I started to have conversations with Western monks, who explained the Gita to me in such a way that I could understand what it meant for me in my life at that moment. I wasn’t Arjuna, the main character of the Gita, five thousand years ago. I was a guy working at a mortgage company trying to figure out my life. We had lost everything, I had moved to Bulgaria, now I’m in New Jersey… It was a roller coaster. I was really questioning the purpose of life, and they were able to help me understand what it meant. These monks had all lived normal lives before they became monks, so you could relate to them as normal people.

I finally decided to get some training as a monk. It wasn’t even really meant to be a training—I just needed to get away from life and take some time for myself. I went to India for a month, in 1999, and I ended up staying for six months in a monastery. When my Indian visa expired, I came back to the US and then I moved into the monastery here in Manhattan. Again, I wasn’t really thinking of becoming a monk. But there was nothing pulling me back into the world, so I said, “Let’s just take another six months, let the retreat continue.” Six months turned into a year. And fifteen years have gone by. It’s the last thing I would have expected to be doing right now. Being a monk was not on the list of things to do when I was growing up in Southern California, going to the beach every weekend, driving cars, and having a good time with my friends.

Guernica: You’ve often taught vegetarian cooking classes at Columbia. I’m curious to hear more about the role of vegetarianism in Hare Krishna spirituality.

Gadadhara Pandit Dasa: Compassion and karma are the two main reasons we follow a vegetarian diet. We understand that we should live our lives without causing pain and suffering to others. It doesn’t take a lot to see that an animal goes through suffering and emotional trauma when it’s killed. An animal-based diet means one is okay with traumatizing animals and letting them die. That would only reduce our compassion and harden our heart and prevent us from loving god and other people. In terms of karma, if we cause pain and suffering to any living being, that pain and suffering is going to come back to us in some shape or form at some point in our life, in this one or the next.

But beyond a vegetarian diet, we want to express our gratitude to god every day, and one way we can do that is through cooking. Whatever we cook and eat, we offer it to Krishna on the altar before. It’s one way of giving back to god. We also understand that Krishna actually eats the food, giving it godly qualities. When we consume what’s left, we become purified in heart and mind by eating food that was sanctified by the touch of god. Eating that food, which is called prasad, or mercy, actually helps us advance spiritually.

Guernica: In your book, you describe cooking as a kind of “transference of consciousness.” Can you explain that?

Gadadhara Pandit Dasa: When a musician really puts themselves into a piece of their music, you can feel their emotional presence when you hear the song. Or with a painter, you can see their mood reflected in that work of art. How can a human being not transfer their consciousness into something that they’re intimately working with? Food can also be very intimate. We’re buying the vegetables, we’re cutting them, we’re cooking them, we’re offering them to god—we have a relationship with that food. We are putting ourselves into that food.

What does a mother do to express love for her family? She cooks for the family. I never really got why, for my mom, watching me eat the food she cooked actually gave her a lot of pleasure. But then I realized, it’s actually quite powerful to cook for someone. There’s a certain warmth and comfort in that food because it’s actually filled with her consciousness, her love, her desire to provide love.

Guernica: In Urban Monk, you reflect candidly on the most apparent sacrifice of monastic life: celibacy. I appreciated your lightness in describing having to avoid hugging women with whom you’ve worked or developed a friendship: “If I see it coming ahead of time, I’ll quickly stick my hand out for a handshake, but oftentimes it happens so fast that I can’t do anything about it.” Is celibacy an ongoing struggle?

Gadadhara Pandit Dasa: Living in an environment like New York City, I think it’s always going to be a challenge. If I were living in the forest, not surrounded by young attractive women, I think it’d be a whole different ballgame. So I don’t think it’s ever something that becomes very easy, though it does become a little easier over time—and also age helps. But there are other things in life more pleasurable than sex, believe it or not. There’s an incredible amount of satisfaction being able to teach and guide others, help people go forward in their spirituality, and help people through their difficulties in life.

The inner satisfaction you get when you help people, I think, is much deeper than some sexual exchange. Because that is ultimately based on the body, whereas taking time from my life to help someone else relieve their suffering is so much more of a human exchange. I’ve been able to do that for thousands of people, and I feel I’m doing my part as a human being, of making myself available for others who are suffering, or of informing them about a healthier way to live. That deep satisfaction is actually incomparable to sex. It’s not just about gritting my teeth and being celibate, sitting around all day long, thinking, “Oh my god, if I could just get married or something.” No, if you’re doing that you better get married right away.

Guernica: Do you think about having a family?

Gadadhara Pandit Dasa: Of course, it goes through my mind. Thinking of leaving what I do, what I love so much, is hard. But it’s something I’m open to and do consider. And hopefully if I do make that transition I can still continue what I’m doing.

I realized when I became a monk that deep happiness had always evaded me.

Guernica: Your book makes it clear that money—its presence as well as absence—played a central role in your childhood and young-adult life. I’m curious about how present money is in your life, now.

Gadadhara Pandit Dasa: Well, here, we’re given accommodations and food. Our basic necessities are provided for. Most of the other stuff I do is on a volunteer basis. Sometimes I get honorariums, but that’s never a factor in whether I’ll accept a speaking engagement or not. I feel like my duty as a teacher is to speak. If they can’t give me anything, I’m still speaking. If they can, I’m grateful.

I was very lost before I became a monk. Even when I had all that money I was lost, because I didn’t understand the purpose of life. I really thought the goal of life was just to have money. That was the paradigm with which I lived. I realized when I became a monk that deep happiness had always evaded me. That’s kind of why I decided to keep living it, because a certain vacancy was being filled for the first time in my heart, by this culture, this life, this sharing and giving and meditating and praying. I’d never recognized that vacancy before—I think most people don’t. It’s there, we fill it with our iPhone and texting and Facebook and Twitter. We don’t want to see that emptiness in the heart, and we distract ourselves with all this other stuff and ignore it and ignore it—but it’s going to explode on all of us at some point.

I sometimes look back and wish I could have come to my spiritual path sooner. But it probably wasn’t meant to happen to me until struggle forced me to look for a different meaning in life. Nothing could have snapped me out of that worldview of money and cars and material things other than something as tragic and earth-shattering as losing everything and going to Bulgaria. I actually needed that to happen to me.

Guernica: In your fifteen years or so of living and working as a monk, at this temple but also at universities and other organizations, do you feel American society’s interest in Eastern spirituality has evolved?

Gadadhara Pandit Dasa: I think the level of openness has increased tremendously. Now I’m actually going into corporations to talk about stress management, mindfulness, humility in leadership. That stuff didn’t exist before. I just did a meditation workshop at Novartis Pharmaceuticals in New Jersey. This is a whole new trend taking place, mindfulness in the workplace. It’s not quite spirituality, but it borders it. Of course, yoga culture is huge—more than 20 million practitioners in the United States—and a lot of it is very spiritual.

Guernica: There are many vocal critics in the Indian-American community who argue that yoga has become commodified, or uncomfortably appropriated.

Gadadhara Pandit Dasa: In this day and age, everything gets commodified. Christmas, what is that now? Gift-giving. I don’t know if Christ is even part of the picture. So it is what it is. I focus my energy on the people who are taking it seriously and want to learn something deeper from it.

It’s also easy to express an opinion—but then go do something about it. I get frustrated at the Indian community’s frustrations [laughs]. I’ve spoken at Hindu summer camps and sometimes Indian parents will say, “We’re afraid that our kids won’t become Hindus when they grow up, please speak to them.” So I say, “What have you done to help your child be inspired to become a Hindu?” They don’t have an answer. It starts at home. You can’t just bring me in to do the work that you are supposed to have done throughout the child’s life. All your child saw was mom and dad leaving home early and coming back late. Ton of toys, brand new car, big house, and pictures of god in that closet that we sometimes open, sometimes don’t.

How can you believe you’re just the body? Really, that’s everything? Then why are we so afraid of death?

Guernica: What about a belief like reincarnation, which is so fundamental to your religious understanding, but particularly difficult for Hindus and non-Hindus alike to comprehend. How do you explain it to people?

Gadadhara Pandit Dasa: In the Western paradigm, a linear, one-life paradigm, it’s hard to imagine reincarnation is true. But when you look at the evidence, and think about the 2 billion people who do believe in this, either they’re all nuts, or there’s some truth to it.

As with the seasons, the moon and the sun, we understand our lives to be moving in a cycle. You’re not born once and you don’t die once. That’s why death isn’t this horrible, horrible thing. It’s one stop on a train, and we’re going to get on a different train after. The moment we die, the soul continues to live on and enters another body. We actually don’t die. To think that we die is actually an illusory concept. Unless you think you are the body.

Guernica: For the rational or scientific mind, it’s an idea that seems implausible.

Gadadhara Pandit Dasa: And from the other perspective, anything else seems totally absurd. You’re telling me we’re just chemicals? I don’t believe that. How can you believe you’re just the body? Really, that’s everything? Then why are we so afraid of death? Why don’t we want to be near a dead body? What about it is scary? It’s not going to jump up at me. Why am I scared of those chemicals and not the ones surrounding me—this chair, these clothes. It tells me that there was something in that body that’s no longer there. Which is what we were actually attracted to.

Guernica: I noticed there’s a funeral home right across the street from this temple.

Gadadhara Pandit Dasa: Every so often you’ll see a hearse pull up and a coffin will come out and you’ll see some people crying, and there it goes, into that funeral home. You can’t help but wonder about the day when you’re inside that thing. Death is as sure as anything else. But too often we go through our lives not thinking about it.

A true bhakti practitioner will see death as a wonderful opportunity to a new life, or a chance to transcend life altogether, and return to the realm where birth and death don’t take place, where time doesn’t deteriorate like it does here. So it could be seen as something very positive: Let me finish my life off serving and helping as many people as possible, and cultivating my own love for the divine as much as possible, so I can be united with the divine. Isn’t that kind of ecstatic?

There’s a church in Italy in which there are sculptures made entirely from the bones of the previous monks. A sign in front of the display reads, “What you are now, we once were; what we are now, you shall be.” Especially in a place like New York, which is filled with young people, we forget that it’s going to happen to us. But when you remember that, then you have to ask yourself: What am I really living for? Death is a reminder of our life, now. Am I doing what’s important? Have I helped anyone up until now?

We come into the world with a certain number of breaths. And we have absolutely no clue when that last breath is supposed to come out of our bodies. What we can do is use the human form of life to connect with ourselves and connect with the divine. At least that’s how I want to die, in connection with the divine. I think the funeral home across the street is a good reminder of that. This morning, a car came to pick me up and it stopped right in front of the funeral home. Luckily, I wasn’t getting out of the car, I was getting into the car.

To contact Guernica or Meara Sharma, please write here.