Miscellaneous Files is a series of virtual studio visits that uses writers’ digital artifacts to understand their practice. Conceived by Mary Wang, each interview provides an intimate look into the artistic process.

Paula Oberbroeckling was eighteen years old when she went missing in her hometown of Cedars Rapids, Iowa. The year was 1970, and the police were dismissive: Girls are impulsive, they told Paula’s mother. They run away. Four months later, Paula’s body was found beside a culvert, wrists and ankles bound. After that, there were more excuses. She was dressed provocatively. She was involved with more than one guy. She thought she was pregnant, and didn’t want to be. The case was never solved.

When Paula died, Katherine Dykstra, author of What Happened to Paula: On the Death of an American Girl, had yet to be born. But the woman who would become Dykstra’s mother-in-law, the fiction writer Susan Taylor Chehak, was around the same age as Paula; she also grew up in Cedar Rapids and the two attended the same high school. Chehak was obsessed with the lack of answers surrounding Paula’s disappearance and death, and spent years investigating the cold case: poring over old documents, interviewing Paula’s family members, and struggling to find a shape for the story. Eventually she asked her daughter-in-law, a nonfiction writer who had recently given birth to her first child, to take on the case. Dykstra had brushed off her earlier attempts at persuasion, but, stirred by new motherhood, she found herself transfixed. It wasn’t only that she wanted to understand who this beautiful, tragic stranger had been and why her life had been cut short. She felt, somehow, like she owed it to Paula to find out.

And so the story of what happened to Paula became, in part, one of inheritance. It’s a story Chehak passed on to Dykstra, but also one that women have been telling each other in broad strokes for generations. It’s a story about the choices women make and those that are beyond our control; about mothers and daughters, pleasure and danger, sex and race and responsibility and risk. Even as she dug deeper into the case and discovered new leads and angles, Dykstra recognized that she would not find resolution. But she thought that perhaps by creating a narrative for Paula, she could get at some larger understanding of what gets passed down between women, and disrupt the injustice and violence embedded in so much of it. “Perhaps because I was a new mother and because motherhood is, if nothing else, a hopeful pursuit, I needed to believe that young women were not disposable and that when a rupture like what happened to Paula occurred, the world would bend and stretch to repair it, to stop it from ever happening again,” she writes.

Chehak shared all of her research, and she and Dykstra traveled together to Cedar Rapids on multiple reporting trips. Dykstra’s book—a gripping blend of true crime, journalism, cultural study, and memoir—is the product of countless conversations and consultations between the two women, over several years. I was curious to know more about how that unfolded, how it changed their relationship, and how their understanding of what happened to Paula Oberbroeckling shifted over time. So I asked if they would take me through these files together.

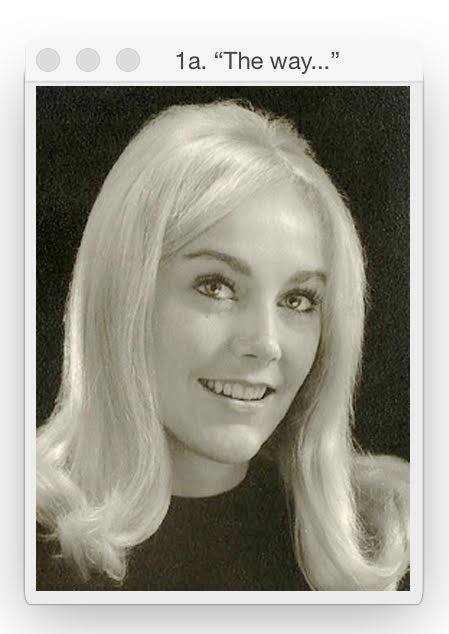

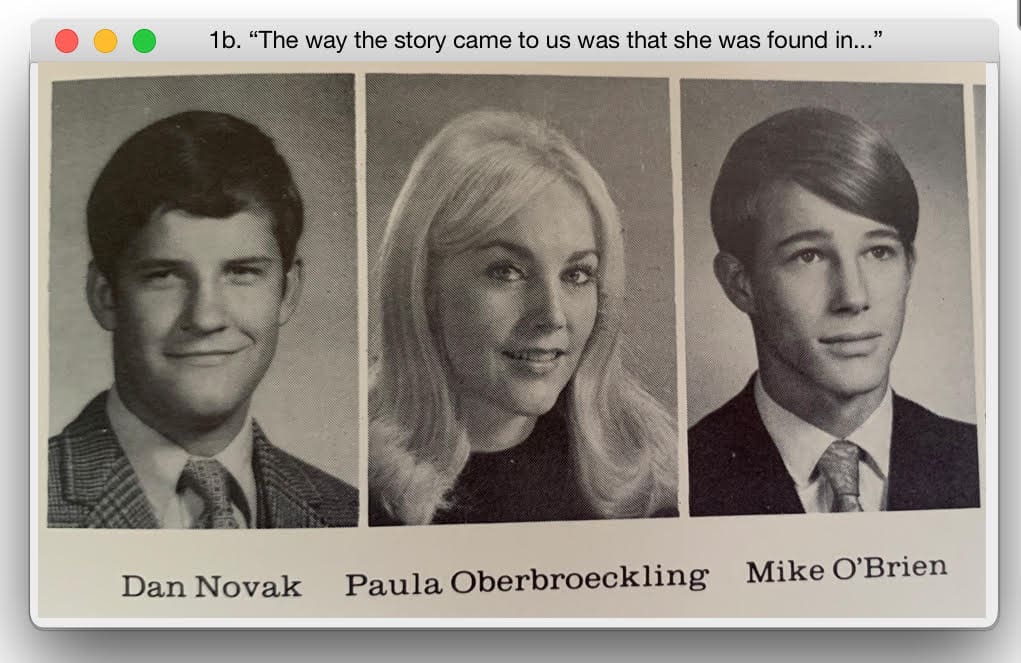

1. “The way the story came to us was that she was found in a trash bag tied to a tree.”

Eryn Loeb: This headshot, which you were told was Paula’s senior picture, was what pulled you in to the project. Much later, you looked at her senior yearbook—the photo that ran there was different.

Katherine Dykstra: When Susan first sent me her files, including the police file and the photographs, I was trying to get a feel for the case and what it was about. I was flipping through all these pictures of Paula and nothing really struck me, they all seemed impenetrable. Until I saw this picture: There’s this glint in her eye and the way she’s lit—it’s like she’s having a moment with the photographer, like she’s challenging him. I know that feeling, when you get looked at in a way that makes you the slightest bit on your toes. When I saw this photo it was like I suddenly saw her; I thought I understood her in a way that reflected my own experience. That was sort of the cornerstone of my reconstruction of her, the thing that really stuck with me.

But then in October, I was going through some last things and there was some reason that I had to go into the Washington High School yearbook. I had used the yearbook mostly to look at Paula’s friends; I didn’t ever actually look at her picture, maybe because I thought I already had it. But when I flipped to her page I was like, Oh my god, it’s not the same photo. And not only is it not the same photo, but I feel like it’s a lesser photo. She’s still beautiful and interesting to look at, but somehow the look in her eyes isn’t as bright or sharp. So I texted Susan immediately and we both went back into our files: The photo I had the whole time was actually the one that ran alongside the story of the discovery of her body, on the cover of the Cedar Rapids Gazette.

Loeb: Susan, you and Paula were a year apart in school. Did you ever actually cross paths with her? What do you remember knowing about her?

Susan Taylor Chehak: She was locally famous. When she came to Washington I was away at boarding school, and I was dating a boy who was in her class. So I heard about her from him and his friends, the boys talking about her. I never heard that she was missing, but I have memories of hearing my boyfriend on the phone, learning that her body had been found. I know exactly where I was, I know where I was standing. And the way the story came to us was that she was found in a trash bag tied to a tree.

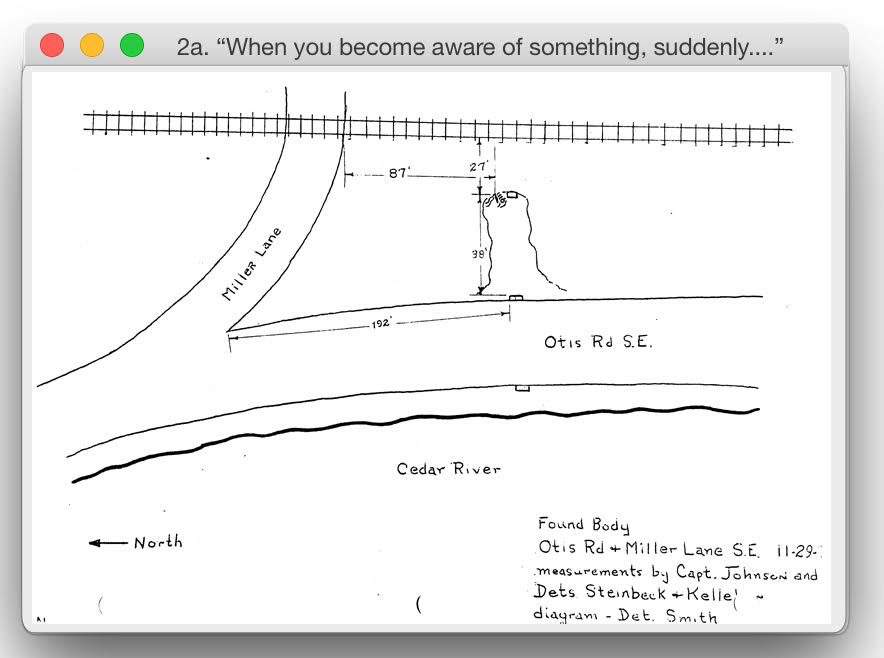

2. “When you become aware of something, suddenly it’s everywhere.”

Loeb: In some ways it feels like a classic missing girl photo. But it doesn’t appear in the book; in fact, on the book cover it’s conspicuously missing—cut out to expose the scene behind it. That scene is where Paula’s body was found, as we also see in the map in the police file, and in photos you took in the winter and summer. Her body was found by the mouth of a culvert. Katie, in the book you reflect on that word, “culvert,” and it seems like it has a lot of resonance for you. What does that word make you think about?

Dykstra: So much of this project was about lighting on one idea and then suddenly seeing it everywhere. For me, Paula became sort of a metaphor for everything. Everywhere I looked, she was there. I felt like I couldn’t turn around without seeing her. Of course, stories of other missing girls would make me think of Paula, but also stories about the wage gap. Women on TV shows made me think of Paula, whether the relationships between mothers and daughters or the relationships between friends, or pregnant women. On a micro scale, it was the same with the culvert. When you become aware of something, suddenly it’s everywhere. It was a word I had never encountered, or if I had I had, it wasn’t important. Julie Benning [another Iowa cold case; Benning died in 1975 when she was eighteen] was also found in a culvert. Their cases were like a mirror. Everything became a mirror.

Chehak: There were dead girl in ditches all over Iowa in the ’70s. Lots of cold cases, unconnected. I had no idea of it at the time. Dead girls in ditches without shoes on. Barefoot. Blonde.

Listen:

3. “That did happen, that did exist. It wasn’t some sort of figment of my imagination.”

Loeb: The word “culvert” comes up a lot in this recording, too, of the two of you at the site where Paula’s body was found. Tell me what we’re hearing in this clip.

Dykstra: Susan and I visited the culvert together for the first time in February 2015. It was very cold and windy and there was probably a foot of snow on the ground. When we came back in August of that same year, it looked really different. In this recording, we’re walking around hypothesizing: Maybe Paula’s body had been left before the culvert and washed under the tracks, and what would that mean for the timing. We’re trying to figure out why it looks different to us.

In the audio you can hear: I see this beautiful blonde bird right there, on a limb around the culvert. It was such a shocking thing to see. Two or three years later, as I was writing, I remembered that moment. It felt too perfect for the story, almost like I made it up, but I was sure that it happened and I left it in. Just recently I was going back through these tapes and there indeed was the moment where I see the bird. There’s something about the shock in my voice. It feels amazing to me that it was recorded. This is a heavily reported book but there are a lot of instances of memory in here, and those things can get kind of loose-y goose-y sometimes, so to have that validation was exciting for me. I have that same feeling when I’m going through old pictures and there’s a memory that I didn’t know had been photographed: Oh my gosh, that’s there, that did happen, that did exist. It wasn’t some sort of figment of my imagination.

Loeb: There was other audio involved in this project too, because Susan had met members of Paula’s family and interviewed them years ago. What was it like to listen to those hours and hours of conversations?

Dykstra: When Susan suggested that I get involved in this story, she had all of those interviews transcribed. So my first experience was of reading them. That was the case for a long time. I had read some of those interviews dozens and dozens of times, and different things would pop out each time. It was only then, when I was truly committed to the project, that I sat down and listened to all of the audio. And then the same thing happened: When I listened to the interview that Susan did with [Paula’s mother, Carol, and Paula’s siblings] in Carol’s home, I could hear them break for water; I could hear them trail off. All those things added to my understanding of the story.

Chehak: The transcriptions had been edited and cleaned up as well. It was a much more polished version of what they were saying.

4. “It was like, am I willing to risk the gains we’ve made in our relationship over this thing that I sensed that you really wanted me to do?”

Loeb: Katie, when you first got this giant, overwhelming pile of stuff, which you had resisted for a while, how did you approach it? Susan, what was it like to hand over that material?

Chehak: For me it was a great relief. When I first got the police file, back in 1999, I remember being on the plane and looking through it for the first time and thinking and writing in my journal, “I have found my life’s work.” It was so meaningful to me and I fell into it as an obsession. Then I had been working on it for so long and I had accumulated so much detail; I had tried to sell it as a book, I tried to write fiction. I was getting to the point where there wasn’t any place to go with it, for me. And so handing it over to Katie was like: “Here.”

Dykstra: The first time Susan approached me with it, back in 2008, I was afraid of it. It was not for me. And then after I became a mother I saw how the unfairness of Paula’s situation was still relevant, and it just felt like something I couldn’t turn away from. I wanted to immerse myself in something I believed in. The more that I learned about it the more important it felt, and the bigger it became for me.

Chehak: On my side of the fence as I was watching this, I’d come back from a phone call with Katie and say to my husband “Yep, she’s hooked. She’s in.” I was completely overwhelmed by how much of the story was there and how important it all was, and then to be able to pass it on to Katie and watch her fall into the same damn rabbit hole was amazing.

Loeb: At the same time, Katie, you worried that if you didn’t make something of the story you would disappoint Susan—that you would have failed her.

Dykstra: I mean, this was my mother-in-law, and our relationship had been tense at times, like many mother-in-law and daughter-in-law relationships.

Chehak: I was so hard on her in the beginning! It’s embarrassing to look back on. The alternative would have been for her to say, you know, fuck off. But that’s not the kind of person she is.

Dykstra: I look at the book now and it feels like a whole. But at the time I didn’t know what it was. I was just interested in this story. When you came to me the second time, things had really mended themselves and I felt like I was in a good place. It didn’t even occur to me that it could be a book until about a year and a half in. Then it was like, am I willing to risk the gains we’ve made in our relationship over this thing that I sensed that you really wanted me to do? There was an odd pressure. Had I not been attracted to it, had I not had my son, it might have been different. Then I might have told you to fuck off. But my own womanhood was at the forefront of my mind; I was seeing how my life has changed and how it made me angry, and how it also felt inevitable. I began thinking about how women’s lives are framed, in ways I hadn’t until that point. I hadn’t had to. And then there was Paula.

5. “At the time I was told: Don’t ever tell anybody.”

Loeb: Two years before Paula died, a woman named Sharon Wright turned up dead behind a supermarket in Cedar Rapids. She’d died from complications from an illegal abortion. It turned out there was a shady abortion ring in Cedar Rapids, and its ringleader was related to a man who was linked to Paula’s case. But while those specific connections interested you, you were more interested in how they point to the larger systemic problem that her death was a part of. Katie, that informed your “choice to turn from the obvious question of who had killed Paula toward the bigger mystery of how society could have allowed her to die.” And it really made the story much bigger than her life and death.

And then Susan, the idea that Paula might have wanted to end an unintended pregnancy prompted you to tell Katie about the abortion you had in 1970, when you were nineteen. Was that the first time you saw your own experience in that context?

Chehak: I did not know, until I got the police file in the ’90s, that there was an abortion story around Paula’s death. And then when I did know, I didn’t make the connection to my own experience at all. When we got the timelines, I realized that my abortion happened at the time her body was found. I told Katie, and she was like, “What? Don’t you think that’s significant?”

Dykstra: It was so shocking to me because you’d always been so forthcoming about your whole experience with the case, and your experience generally. I didn’t think of you as a person who would deliberately withhold anything.

Chehak: Absolutely. It was unconscious, until you said that. Then I was like, oh yeah, that’s interesting. We’re connected. I had not kept it a secret, it was something that was absolutely well known in my family, by my children, by my husband, by everybody. Although at the time I was told: Don’t ever tell anybody.

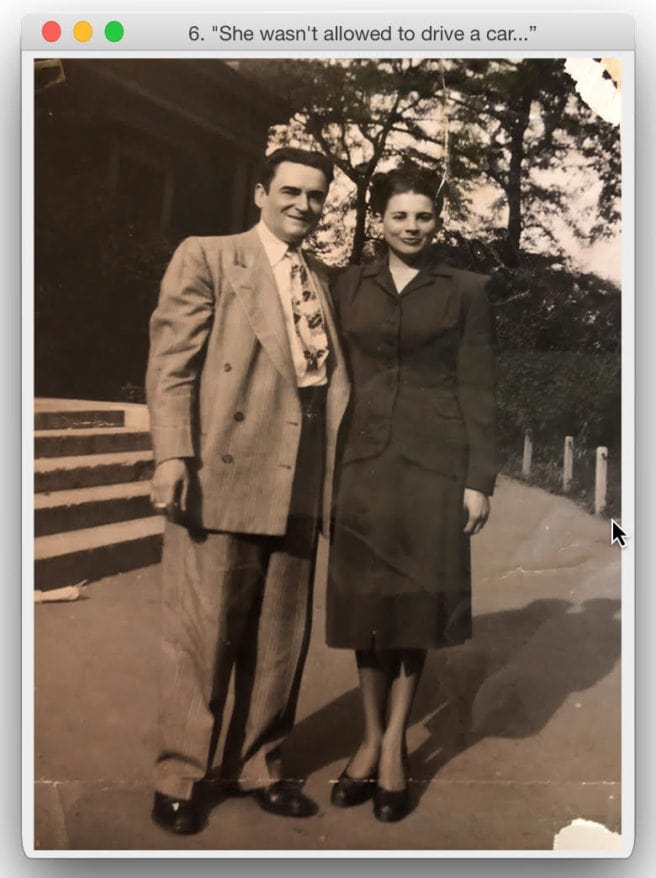

6. “She wasn’t allowed to drive a car; he kept her at home under his thumb.”

Loeb: Katie, that brings me to this photo of your grandmother, who you also write about in the book. You were really close to her growing up, and she was a complicated figure. Her life was full of trauma—unwanted pregnancy and shame figure into it, too—but the true story of it was pretty hard to untangle. When you look at this picture of her, what do you see?

Dykstra: This picture was in my childhood home growing up. My grandfather was a very difficult, sort of aggressive, dictatorial type. My mother has a very complicated relationship even with his memory. He laid the law down in that house, he was the be-all and end-all of everything. I think it was a very stressful home to grow up in. He was twenty years older than my grandmother, and he died when I was very young. So there were never any photographs of him in my house—except for this one. But when I asked my mother to send it to me, I was shocked that my grandfather was in it. I had edited him out. I asked my mom, “Is there no picture of Grandma by herself?” and she said, “I wish.” In fact, I had made this picture just about her, even though he’s right there. Memory is very slippery.

My grandmother just looks so beautiful and put together. And she is so young. She had such a hard youth: She was abused horribly by her own mother, so much so that she ran away from home at sixteen years old and went to live by herself and was going to make her own way. She wasn’t educated. She had nothing, no money, no family support. And she wound up pregnant. The man disappeared. She was seventeen years old and had nothing and the doctor she went to for help was my grandfather. [That was when the two met, and with his encouragement she went to stay at a maternity home for the duration of her pregnancy.] But in this picture, by this time, she’s had the child and she’s married to this successful physician. I think the look on her face is like, I made it. I’ve done it. I’ve turned my life around after all that heartache and hardship; it’s going to be better. But the thing that crushes me is, it wasn’t. She barely did anything with her life. She wasn’t allowed to: She wasn’t allowed to drive a car; he kept her at home under his thumb. But here she looks so hopeful to me.

7. “The high water mark is sort of a joke.”

Loeb: The Flood of 2008 became a symbol for you. In this photo from a bar in Cedar Rapids, we see a sign indicating where the flood line was, it seems to be there as a kind of memorial and pride in surviving, that’s almost kind of tongue-in-cheek: Can you believe it was this bad? Can you believe the water was up to here?

Dykstra: Everywhere you go in Cedar Rapids, there’s evidence of the flood. It is still so present there. It’s a constant, and I started to think about how one of the ways that we get through trauma is to hold up the fact that we survived. I felt like I began to see that in Cedar Rapids: This happened but we’re still here.

Paula died more than fifty years ago and it was buried: There’s nothing to see here. There’s a sense that if we don’t talk about something it’s not happening. But the only way to get through something is to talk about it. The flood became this metaphor for a way to get through trauma: to hold it up. And Cedar Rapids did that. It wasn’t perfect—there’s a lot of infighting in the city and disagreements about the way forward—but what they’re not doing is saying, We’re fine how we are, we don’t need to move forward.

Chehak: That is part of the ethos of the Midwest in general, Iowa in particular and Cedar Rapids especially: We’re fine. Everything is fine. So the high water mark is sort of a joke. And that ethos goes even further, to the point of putting under the rug disagreeable things like abortion, like pregnancy.

Loeb: Katie, you started the story relating to Paula, but ended it relating to her mother, Carol. Susan, who did you relate to?

Chehak: I definitely related to Paula. I really disliked her mother and her sister; they were the kind of women who I felt made the place worse for everybody. And I felt like Paula was the victim not only of the town itself—the detectives, the men involved, all of that—but also of these women. She was different from them. And that’s why I loved her. That Paula was who she was, and was straying from the norm, made it possible for people to blame her for her own death. And that happened, and still happens, over and over.

Dykstra: In the beginning, when I was first being introduced to Paula, the thing I gravitated toward was the thing that I related to, which was her girlhood, the carefree, risky, fun teenage girl. I think teenagers have a right to be figuring themselves out, and learning their bodies and minds in their own way. That was something I really related to as somebody who was all over the place in my own teen years. My mother was not pleased with me, just as Carol was not pleased with Paula. But I don’t think that should put us at risk of dying. I disagree with a lot of the decisions Carol made but I also see how protecting children is a really precarious thing; I don’t really know how to do it with my own kids, and I’m already sort of nervous about what it will be like when my daughter is a teenager. So over the course of the project I did come to relate to Carol.

Loeb: There’s some tension between who you want Paula to be and who she seems to be. You write, “I wanted her to be a symbol of feminine power, a woman who’d exercised choice and freedom, someone ahead of her time who’d become a casualty of being born too soon.” And yet: “I wondered whether I was giving Paula too much credit, whether I was projecting onto her the things I thought would help condemn society for her death.” Were there ways you tried to resolve that?

Dykstra: Whether she was who I want her to be or she wasn’t; either way, all of these things still conspired against her. Whether she was giving the finger to the cultural norms of the time or whether she was floundering forward as I saw myself doing at sixteen, seventeen, eighteen—she’s the same. If she weren’t dating Robert [who was Black], if she wasn’t possibly pregnant…it’s my contention that there would have been something else.