My sister Maryam and I arrived home from school one afternoon, and Baba announced that we were going to the neighborhood park. We squealed with excitement and followed him outside, where he was jogging in place, a goofy smile plastered on his face, his tan tracksuit baggy on his slender frame. We trailed behind him on the mile or so run to the park: a small bespectacled brown man, his lean, bearded cheeks filling up with air that he forced out in a rapid whoosh, whoosh. And behind him, two tiny girls—seven and five years old—trying desperately to keep up.

Maryam and I gleefully watched Baba traverse the playground, from one piece of equipment to another, like an obstacle course. We followed him on the monkey bars, mimicked his jumping jacks, tried to sit on his back when he did pushups. I relished these outings for briefly pulling me out of our apartment, for helping me forget the feeling of limbo that hung over us each day. Our lives felt unwieldy, stretched taut across two countries, forever in search of ground to plant our roots.

On our walk back, I grabbed Baba’s hand, warm and comforting in the cool Northern California air. As we approached our apartment building, Maryam and I raced to it, running up the steps to the door, where we were greeted by the smell of Maman’s dinner—the herbal aroma of ghormeh sabzi that wrapped itself around us like a doting relative. Inside, she lifted the lid of the stew pot, steam obscuring the frown on her face. She looked up, not at us, but at the television across the entryway in the living room, blaring Leila Forouhar songs against images of my smiling Uncle Masoud. He had been married in Tehran the previous year, but we couldn’t go. His wedding video arrived in the mail weeks later, and Maman played it on repeat. Soon, she could name the relatives in every scene—digital replacements for the real thing—without ever glancing away from her cooking.

Baba disappeared into the bedroom for evening prayer, and I could feel a thick haze of sadness settle in the room. I walked into the kitchen and wrapped my arms around Maman’s legs. She didn’t seem to notice. Uncle Masoud smiled as he greeted his guests. “Look at how handsome he is,” Maman said to no one in particular. I looked up at her and nodded. I wished she would stop missing him. I wished we were enough.

In Persian, there is a word—ghorbat—that evokes the uncomfortable feeling of being alone, of not belonging, in a foreign land. Maman used it often, typically in moments of frustration or resentment. “I’m tired of this ghorbat,” she’d say after an argument with my father. And while he brooded in the bedroom, she’d tell my sister and me everything she was feeling; she had nobody else to confide in. This is how we became the vessels for our parents’ pain, the bearers of their truth.

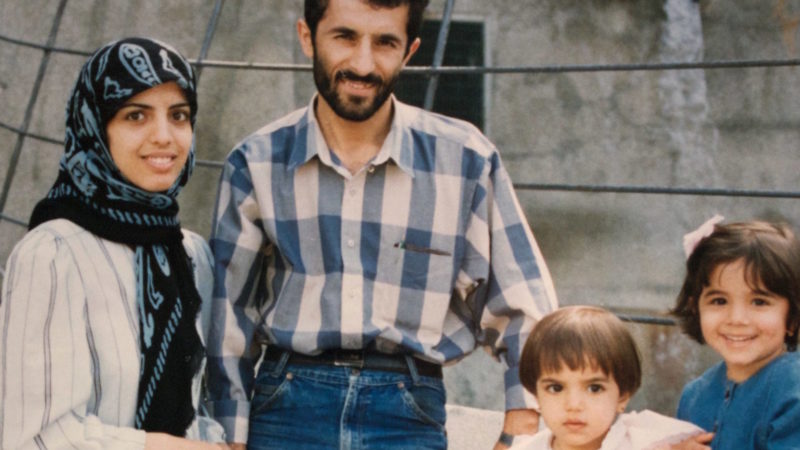

My family’s story in America is as old as I am. My mother was 21 and pregnant with me when she, my 29-year-old father, and my one-year-old sister immigrated from Iran in 1986. They left, it seemed, without looking back, with hardly any time between my parents obtaining their student visas and boarding the plane. I was born four months after my parents settled in California, and for much of my childhood, I unknowingly supported my parents and sister with the benefits of my US citizenship. My father told me that, hours after I emerged from the womb, the nurses at the San Francisco hospital approached him with documents detailing options for health services, discounted public housing, and forms to apply for food stamps. Until then, my family didn’t know about welfare. They had been scraping by at motels and friends’ houses for months. Baba guarded the information the nurses gave him like a precious secret, whispering it to his wife shortly afterwards.

Years later, when I was old enough to understand, he told me they’d never have been able to make it in America if it wasn’t for me.

As an eight-year-old, I used to look outside my bedroom window and search the skies for signs of storms: a sliver of dark shadow bordering white clouds, a dense buildup of fog in the distance, the smell of rain right before it hits. If the sun hid behind the clouds, blanketing my world in gray, I felt my heart beat heavy and fast, each second swelling until I could barely breathe. When it rained, I worried about flooding, car crashes, and death. I had this fear, not necessarily of storms or thunder, but of impending doom, and I scanned the clouds as if I could read them like tea leaves.

Even before I knew I was the only American citizen among us, I felt responsible for protecting my family. I did this by paying close attention. My mother often tells me that I am her most attentive child. If she struggled to remember a phone number or a new acquaintance’s name, or if her English failed her at the grocery store, I would appear beside her, the solution on my lips. Our household was loud and tumultuous. We talked over each other at dinner; we watched television at high volumes; we argued loudly and passionately about trivial things. Amidst the chaos, I’d retain snippets of important conversations I overheard between my parents, details I unconsciously stored in my memory and could recall at will.

We had moved to Pennsylvania after my parents were accepted to the University of Pittsburgh, where my mother planned to study dentistry and my father planned to continue his engineering studies. In California, they had packed up all our possessions and crammed them into our two-door silver Mitsubishi coupe. Maman slammed the doors shut, pulled out her TripTik maps to Pittsburgh, and called it a new beginning. She had spent most of her days in Berkeley trying to forget her homesickness, taking a few community college courses, learning English by watching soap operas or Sesame Street, and caring for her children while her husband worked and went to classes. She was impatient. Baba looked up at the car’s headliner and said a prayer before he started the engine, sealing our family’s hopes in a quiet confession to God.

For our first few weeks in Pittsburgh, we stayed with an Iranian couple my parents became acquainted with through mutual friends. They lived in a one-bedroom apartment in Pittsburgh’s Oakland neighborhood, and though my parents likely felt they were imposing in such a cramped space, the couple’s home never felt small to me. In the evenings, my family and I slept on cushions and thick blankets laid out in the dining room; every night felt like a slumber party. During the day, while Maman and Baba went apartment-hunting, Maryam and I lounged in the living room, watching VHS tapes of The Wizard of Oz or Sleeping Beauty.

My parents eventually rented a two-bedroom apartment in South Oakland, an area popular among party-going college students who wanted to live off-campus. On days when Maryam and I didn’t have school, we’d tag along to classes with our parents. We’d sit in the back of vast, dark lecture halls, dolls or coloring books in hand, watching Baba or Maman feverishly take notes. In the evenings, they’d stay up for hours reading and re-reading their textbooks, trying to fill in the language gaps they worried would hold them back.

Within a matter of months, my parents realized they had taken on too big a financial burden. They were forced to file for bankruptcy and their student visas expired, rendering us undocumented and broke. I listened carefully to their whispered discussions about thwarting the INS, about finding work without the proper papers. I learned that we survived because of the food stamps and Section 8 housing my birth granted us. The realization made me feel terrified of my own power and responsibility. I began saving everything: my parents’ old credit cards, receipts I found in the trash, junk mail that seemed important. One of these things holds an answer, a solution to our problem, I thought, though it was a problem I couldn’t name. At night, before I went to bed, I wrapped a tiny pink and purple Chuck E. Cheese fanny pack around my wrist, full of coins I had collected off the street. If our building burns down, I thought, I’ll have money for food.

Years later, as I try to fall asleep at night, I feel the same sinking feeling I felt as a child searching the clouds for signs. My mind clears of the day’s events, and all that’s left is everything I will never know. Sometimes, I look out the window at the night sky, straining my neck until I can find the moon. On clear nights, she is bright and watchful, but somehow, it is not a comfort. Somehow, it feels like she can devour me in an instant.

One night, when we were still living in California, Baba was mugged at gunpoint. I remember it clearly, though the memory is not mine. On his way home from work at a gas station in Daly City, he stopped at an ATM for cash. As he pulled the money—a $20 bill—from the machine, he heard a deep, disembodied voice behind him: “Give me the money.” He froze, his breath quickening, his heart pounding in his ears. From the corner of his eye, he caught a glimpse of the gun that pressed into his lower back. Moving cautiously, he passed the bill behind him. His assailant grabbed the money and ran.

Baba told us this story at dinner shortly after that night. His tone was lighthearted as he downplayed the fact that his life had been at risk. “The poor man probably needed the money for food,” he told us. He smiled to himself, as if he was grateful to have had the opportunity to help. Baba loved Westerns; he grew up on dubbed black-and-white images of Clint Eastwood and John Wayne. The robbery probably felt like a rite of passage for him, ushering him into his rowdy American life.

But I thought about it often. If my parents died, I worried, Maryam and I would have no one. I agonized over who would take care of us, how we would provide for ourselves. I had never met our relatives in Iran—to me, they were a combination of blurry photographs, tear-stained letters I couldn’t read, and static-filled voices I struggled to communicate with every month on our landline. My parents never told them much about our lives in America. Maman refused to give them the impression that we were living paycheck-to-paycheck, that we were lonely and scared—realities too shameful to confess.

Our secrecy was necessary, given our precarious status. But it made us weaker. When my parents fought—about finances, family in Iran, or their children—our apartment would transform into a pressure cooker of festering resentment and sorrow. Maman’s anger built like wildfire, while Baba thought that if he stood cold and unwavering, a statue of ice, he could extinguish her fury. Instead, the heat welled up inside her as she grew angrier at not being seen. I dreaded the aftermath. Baba grew silent and distant for days, and Maman poured her heart out to the only people who would listen: her young daughters. I tried to patch things up between them, serving as a messenger, running from living room to bedroom to explain one side to the other. My family collapsed into itself in this way, as my sister and I tried to build reinforcements. We learned to bury our secrets in the rubble.

After my parents lost their visas, Baba struggled to find work and sought help from the local mosque. The imam told him about Pasha, an immigrant from Pakistan who owned a mini-mart in Pittsburgh’s Bloomfield neighborhood. Pasha was willing to hire undocumented immigrants and pay them under the table. Baba took the job. He and a Syrian immigrant worked the cash registers, arranged groceries on the shelves, and swept the floors. His hours were unpredictable, and he was hardly around during the day. Whenever he worked the night shift, I lay in bed, wide awake, until I finally heard his keys sound their familiar jingle. I counted his footsteps as he stepped inside, and pretended to be asleep when he stood in the doorway of the bedroom I shared with my sister, taking in the peaceful image of his sleeping daughters.

One night, after he came home, I stayed up and tiptoed through the living room and down the hall to my parents’ bedroom. I stood outside the half-open door and saw Maman sleeping. Next to her, the bed was empty. I searched for Baba in the dark room, worried that I had imagined his return home. Then I caught sight of movement in the bedroom mirror and, my eyes having adjusted to the dark, watched his reflection as he prayed in the corner of the room. He bent at the waist, stood, and prostrated. “Sami’ allahu liman hamidah,” he said, God hears whoever praises Him. I watched him in the mirror as he stood again, adjusting his feet for the second rakat. But his reflection showed him doing it all wrong, standing opposite to the qiblah, his hands raised away from Mecca.

Death is always on my mind, though I’ve never come close to it. As a child, I worried that losing my parents would leave Maryam and me to fend for ourselves, alone in ghorbat. In adulthood, my fears have not changed, though I have more words to describe them. I worry about the unknown—the when, why, and how of death. I worry about losing my parents and trying to make sense of myself in America without them. I fear losing my only connection to my ancestral homeland, Iran—a country I have visited only a handful of times, each trip an overwhelming barrage of emotion that stays with me for months until it dissipates. I worry about maintaining my Persian culture and language when my parents die, and whether I am up to the task. I fret over what I will teach my future children without my parents’ guidance. I feel constantly uneasy, unmoored.

These worries drive me to take precautions. Sometimes, when I visit my parents, I pull out my phone while we are talking and hit record on the voice memos app. Other times, I interview my parents, asking them specific questions about their lives in Iran and their beginnings in America. Every time, I have more questions. The older they get, the more I am forced to confront the reality that one day, I’ll realize I failed to ask them everything I needed to know.

I have had this urge to observe and document the world around me since childhood, a habit I trace back to my early desire to protect my family from an America I believed I understood better than they did. As a young girl and adolescent, I diligently kept a journal. I enjoyed watching shows like Dateline and Unsolved Mysteries; I filled my diaries with mundane details that, I believed, would make any case-cracking detective proud. I have old cassette tapes from the years in middle school when I kept an audio diary.

Now, in my early thirties, as my husband and I prepare to start a family, I pepper my parents with questions, not only because I am concerned with protecting them, but because I believe that their answers will protect me. That when they’re gone, I will be able to remember their words and feel rooted in a country that has, for so long, held my family’s fate in the balance.

We were all we had, I tell Baba during dinner one evening. He smiles and shakes his head. “Every step of the way,” he said, “we had help.” The nurses at the hospital where I was born. The imam at the mosque. Pasha. Friends who let my parents stay with them in those lonely first years.

“And me,” I say, jokingly, referring to my citizenship. But I don’t want him to praise me for it. I want him to tell me that we’d have made it with or without my lucky birth.

“And you,” he says, smiling. “We had help, also, to become citizens.” When they became undocumented, my parents had little idea of where to turn, and were wary about who they could trust. One of Baba’s friends from the mosque told him about a Muslim lawyer based in Chicago, who exclusively helped undocumented immigrants. “He was the one who pulled us out of our illegal status,” he says. The process took years, but my parents were eventually able to secure work visas and, finally, green cards. They became citizens when I was in high school, one year after 9/11, though I don’t remember it. Nearly two decades had led up to that moment, and while my parents were relieved, I don’t think we ever celebrated. We were all Americans, but by then, with racism a frequent visitor in our lives, we realized documentation couldn’t protect us from everything.

“Was there ever a moment,” I ask Baba, “when you wanted to give up and return to Iran?”

“Never. To return would be failure,” he says. “And this was always my dream.”

“America?” I ask. I want him to say “yes.” I want him to tell me this country was meant to be ours. Maybe then, I can finally relax, allow my roots to stretch out and find ground here.

“Kharej,” he says. Mostly, he cared about leaving Iran, seeing the outside world. “And now, look at us!” He gestures around the large family room of their suburban home, a grin spreading across his face. That small apartment is many years in the past. “We made it.”

My family’s material achievements—the house, the jobs, our US passports—are, to Baba, proof that we’ve succeeded. Even now, though, the sense of ghorbat doesn’t fade. It is passed down, a longing that is not bound by generation. It is why we cling so tightly to one another, why I write everything down, why I still worry that the worst is yet to come. In times when I feel especially uneasy, I picture an Iran that is, politically, within reach. I imagine traveling there regularly, accessing the part of me that seems out of reach here. I know what I’m missing is more than a country. Neither Iran nor America can make me feel whole. But every word I write of my family’s stories helps the cracks deep inside of me mend.