This has been modified from its original version. It has been formatted to fit this screen.

If you were walking down Sunset Boulevard in mid-January—right around the time America’s forty-fifth president (a man and a president fit for his time) was inaugurated—you may have come across a familiar, though half-forgotten site: the façade of a video rental store. Through the window was the usual setup: movie advertisements, shelves of VHS tapes, genre signs, a gum ball machine, a couple dorky clerks chitchatting behind the counter, even a curtain with the label XXX, beyond which, you might guess, you could sneak a glimpse of videotaped smut. What was different about this video store—besides the fact that it was 2017, not 1997—was that all the tapes, all the posters, even the celebrity cardboard cut-out and the genre signs plastered high on the shelves were for the same movie: Jerry Maguire. Indeed, it was the only movie available in the entire store, and none of them were for rent. These fifteen thousand “Jerrys,” as they are affectionately known, were put on display by the video/art collective Everything is Terrible! (EIT!), which has been mashing up videos and collecting copies of Jerry Maguire video tapes for about eight years.

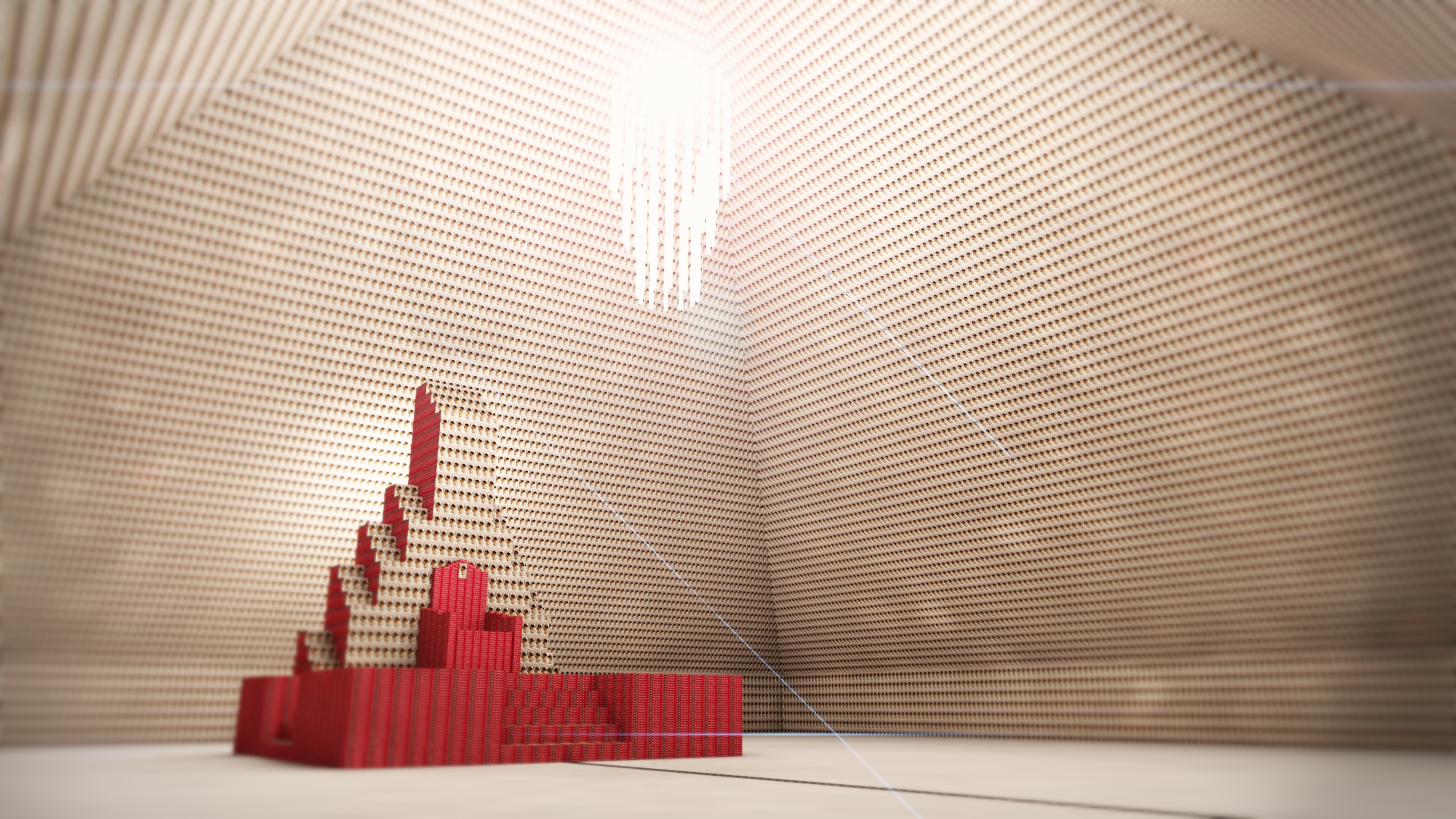

On opening night of the exhibit, I watched as about a thousand of LA’s video nerds and scenesters streamed past the wall-to-wall red-and-white Jerry shelves, through the XXX curtains, and into an ankle-deep pool of unspooled Jerry Maguire, wrapping their arms around a cardboard cutout of Tom Cruise talking on his mid-90s flip phone to pinch-zoom and snap Instagram/Facebook/Twitter-ready photos. What (the fuck) to make of this? The store was a meme, hypertrophied and incarnate. Jerrys stacked into pyramids along every wall. Jerry-inspired art selling for hundreds of dollars. Jerry socks. Jerry mix-tapes. A Jerry video game. A treasure chest of still shrink-wrapped Jerrys sent from an adulatory Cameron Crowe (the film’s director). And then the actual (fucking) pyramid—the actual pyramid EIT! is in talks with actual architects to build in the actual desert—a tomb and a shrine “for all the Jerrys to live in for all time,” according to Nic Maier, one of the lead members of the video art collective. Was it Scientological mission creep? A Malkovichian nightmare? A glitch in the matrix? Or a mirror held up to an entire media-drunk generation?

Everything Is Terrible!’s art—a collagist paean to video kitsch—is a sort of technological ekphrasis: a eulogy for one technology through the medium of another. Members of the collective scour thrift stores for video arcana—bizarro exercise tapes, religious propaganda aimed at children, cat massage instructional tracts, farm animal yoga, and job-training videos we were subjected to as pimply teens—splice out the weirdest and most cringe-worthy clips, and upload, revealing the hyper-consumerist age of technology for what it is: navel-gazing, backsliding, and blind—one which spawned the most successful (though abiotic) parasitic form since lice: the smartphone. EIT!’s turretic, share-ready, VHS clips, however, also function as a sharply critical lens to lay bare the hyper-capitalist racism in the center of all the media-frenzy.

Besides posting short videos on their site and YouTube channel, EIT! produces feature-length movies (including DoggieWoggiez! PoochieWoochiez!, a remake—created entirely with found footage of dogs—of Jodorowsky’s acclaimed art-house film Holy Mountain), and takes their work on the road with video/live performances in which long-limbed, fuzzy, extraterrestrialish puppets introduce cut footage and push the collective’s ideology of sardonic (or maybe celebratory) nihilism. Their style, though hard to pin down, combines the essence of the Masonic occult, Christmas kitsch, and early ’90s white rap. Their palette is pastel and white noise. Their vision is cyclopean. Their energy is strobing, red-eyed, hysterical.

In 2013, after several years of cringe-worthy, eyebrow-raising cutups, EIT! was given access to an entire vault of amateur footage, courtesy of America’s Funniest Home Videos, and began a new series, Memory Hole, which competes for some of the most depressing bandwidth on the web. Sad, often disgusting, pathetically sincere cries for meaning from middle-America’s carpeted living rooms, circa 1995. The only laughter these videos elicit is choking and horror-stricken. See their video “Picnic In Hell,” in which two people act out what seems to be the prelude to a real-life horror film—one person serving and slinging spaghetti with their toes, the other holding a live chicken in their mouth and going ruff-ruff like a dog. The video is date stamped, for posterity, March 11, 1997. (Jerry Maguire was almost definitely still in theaters.) I often think, when witnessing these videos, of the Spanish term pena ajena: literally, pity for the other, or being embarrassed for someone else, though the feeling often goes far beyond embarrassment. EIT! seems to exemplify something more: pity for the world. Pena mundial.

Like a dog to his own media vomit, I’ve been drawn to EIT!’s video spectacle since the early years. I’m an old friend of various members of the collective, have—magnanimously—donated a dozen or so Jerrys myself, and have even tagged along for a few stops on one of their Christmas-themed tours, standing in as a giant, eye-glowing, benignly demonic Santa Claus. The absurdity, the exclamatory insistence on everything being terrible, the regurgitated media camp—all of it appealed. But not until I saw the Jerry video store did the multivalent tones of media-obsession and ostentatious cynicism fully cohere into a relevant critique of contemporary culture. I never doubted the artistic or political instincts behind the collective’s project, but mostly I just laughed along, not understanding the depths behind projects like their second feature, 2Everything2Terrible2: Tokyo Drift!, a blistering exposé of media’s culturally appropriative, hyper-capitalist underpinnings. The painful to watch, pitiful, dada-like absurdity of their work is a cutting examination of the capitalist-driven media-entertainment juggernaut as it rumbles from media dyspepsia to media ubiquity. It is also an appraisal of our role, as media consumers, in greasing the juggernaut’s wheels.

Rental Store Fetish

Jerry (fucking) Maguire, the 1996 film directed by Cameron Crowe and starring Tom Cruise, Cuba Gooding, Jr., and Renée Zellweger—racist and misogynist to its core—is an obvious choice for the recreated rental store/pyramid to explicate the headlong late-capitalistic rush that was thinly masked over, for a few years, by the democratic dreaminess of social media. Maier, in speaking of the dueling evanescence/permanence of today’s media, said of the movie: “It’s insane that this thing, this beautiful thing, was created, loved for a second, and then thrown in the trash.” Sic transit gloria mundi, and yet our trash, of course, does not simply disappear after we haul it to the dumpster.

The bizarre, surreal, and nearly overwhelming experience—walking into an all red-and-white store with thousands of Jerrys lining the shelves—was expertly neutralized by the underwhelming familiarity the conceit was enmeshed within. Every detail was, eerily, recognizable. I felt like I was walking back into my suburban childhood: the thin red carpet, the dress code of the clerks (red Jerry shirt, khakis, brown shoes, and brown belt), the “This is What Happens When You Leave a Jerry on Your Dashboard Sign,” complete with a melted VHS tape hanging from a string; the return slot cut into the counter; the XXX curtain; the laminated membership cards. It was a videotape web of time past.

This gap, between underwhelming and overwhelming, is of particular concern for capitalism. The Factory Acts, implemented in nineteenth-century England, scaled back oppressive and demanding workplace conditions not for the sake of the workers, but to keep the workers working—to sustain their presence in an alienating environment, to scale back that feeling of being overwhelmed, and so prod them towards ever greater productivity. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration fulfills a similar role today—keeping workers safe so they can keep working. Likewise, shopping centers and shopping markets strive to offer customers everything they want, but within such boundaries that they aren’t paralyzed by a near-infinitude of options. Retail space—the analog equivalent to the Amazon search bar—normalizes an inherently alienating experience. It masks the distance between a product and our consumption of it.

The capitalistic consumption of films exemplifies that distance-shortening: you can observe the rich and the famous within the confines of your living room, as if your world was theirs and vice versa, simply by renting a VHS tape or, today, by streaming media online. The Jerry Maguire Video Store both accentuates and diminishes the viewer/renter’s sense of alienation. The absurdity of a single-movie rental store calls attention to the industrial relationship itself, and at the same time the detailed reproduction of the space—playing on nostalgia—softens the feeling of overwhelmingness/alienation. As factory owners (at least in the global north) have learned to steer towards the sweet spot between worker productivity and worker exploitation, marketers and store managers similarly navigate between inciting desire and inciting disgust: superfluity glistening in fruit pyramids within blocks of starvation; media glut balanced by declines in literacy. This, in part, was EIT!’s project: you witness a stomach-turning display of overmuch—fifteen thousand (fucking) Jerrys—but at the same time your experience is normalized by the familiarity of the setting, the uber-comfort of the rental store.

Harnessing Awe: The Sacred Is for Adults Only

The pyramid, however, does the opposite of softening. It defamiliarizes; it turns the corporeal sacred. The pyramid signifies that you should approach with caution. “You have to go inside: that’s part of it,” Maier said. You have to cross the boundary, consummate the choice. You have to pick a video.

The hysterical psychedelia of EIT!’s videos reveals not only the nonsense present in almost all Hollywood creations, but also the cultish influence of Hollywood not as art incubator, but as capitalist scaffolding. The pyramid—with all of its occult symbolism—is the heart of media and entertainment: the self-celebratory galas, the drone swarms, the impossible costumes, the incestuous celebrity-palace intrigue. It is no wonder that the enormous collection of Jerrys is going to live in a pyramid “for all time,” according to Maier—to be found by future archaeologists, or aliens, along with L. Ron Hubbard’s stainless steel tablets. “Keep Doing God’s Work,” one fan wrote in a note to the collective, sent along with a package of Jerrys.

The pyramid represents exclusion, predestination, lack of choice. Thus, while EIT!‘s recreated video store takes “the renter” through the false (and historic) space of ’90s-era choicefulness, of weekends summoning the divine into your family room, celebrating the exceptional democratic experience of access, possibility, and hope, the Jerry pyramid lays bare the violence of this falsity: only the priestly or penitent enter the pyramid, only the wealthiest, the most powerful, the most blue-blooded are enshrined. The plebeians or slaves may lay the bricks, they may awe or ogle, they may pay their respects in tithes, likes, or sacrificial blood, but they must stay on this side of the velvet rope. The pyramid, like the Hollywood sign, is a symbol of unattainable dreams, and yet it encourages dreaming, an act Wolfgang Streeck calls “the most powerful impediment to political radicalization and collective action.”

The Dialectic of Adumbration

The rental store exists for you to submit cash to the media industry, to spend two hours passively perpetuating a racist/capitalist/misogynist view of the world. Adorno and Horkheimer couldn’t be more accurate when, writing seventy years ago in The Dialectic of Enlightenment, they wrote of culture “infecting everything with sameness.” The apparent variety of choice in a video rental store masks the true paucity of choice: no matter what video you choose, you’re going home with Jerry Maguire. Adorno and Horkheimer: “The truth that [movie studios] are nothing but business is used as an ideology to legitimize the trash they intentionally produce.”

EIT! commodifies an already commodified art form. Unlike the mathematical double-negative, however, commodifying the commodified does not shield an object from the dagger of the minus sign, or from the market’s rampant thingification. And that’s EIT!’s point—they are amplifying the essence of the industry (as their name unironically suggests), not offering a “better” or “less terrible” vision.

In “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” Walter Benjamin writes how our changes in perception (and consumption of media) influence and ultimately change our entire mode of existence. Today, our sense perception, as well as our self projection is increasingly channeled through mobile screens. We know ourselves through the mediums we wield. We embody our online persona, and not the reverse.

Benjamin: “To pry an object from its shell, to destroy its aura, is the mark of a perception whose ‘sense of the universal quality of things’ has increased to such a degree that it extracts it even from a unique object by means of reproduction.” While a Jerry tape is by no means a unique work of art, the movie itself so embodies the idea of “Movie” that it could almost be titled as such. The plot, the acting, the score—none of it matters, none of it impresses. It was produced, distributed, quoted, and celebrated as an end in itself—the superstructure (the paying audience cowing before the flashing screen) is the sine qua non of the media/entertainment industry. The scenesters stream in; they unholster their screens; they shoot; they upload. The content is superfluous.

In Don DeLillo’s novel White Noise, the “most photographed barn” represents the empty cultivation of aura—that the act of viewing is as important to aura as the object itself. The barn’s reputation outweighs and surpasses its physical presence. Viewers, tourists, and photographers are drawn to the barn because it has been viewed, visited, and photographed before. Instagrammers similarly cultivate aura with every new popular Instagrammable location, backdrop, or food item, uploading not because they like the movie or the location or the dish, but because through the stars, the scene, or the restaurant, they are cultivating an aura. They effortlessly participate in aurification. The shared digital photograph becomes the means by which the consumer makes conspicuous consumption conspicuous. In turn, we cultivate our own auras through the conspicuous aurification of the “most photographed barn” or the Jerry cardboard cutout. The German term of this is Vergesellschaftung, which Streeck defines as “an act of purchase—concluding, as it often does, a lengthy period of introspective exploration of one’s very personal preferences (read: laps around the video rental store)—as an act of self-identification and self-presentation, one that sets the individual apart from some social groups while uniting him or her with others.” Of course, posting a selfie isn’t exactly a purchase, but, by commodifying an image of the self and the “barn” (the Jerry Store), by submitting to the market waves churned up by social media, you turn the wheel of a capitalist relationship between owners and laborers: submitting yourself to advertising and propagating advertisements for profit’s sake. (Or, maybe better said, for the prophets’ sake: the late Jobs, the rising Musk, the ubiquitous Bezos, the baby-faced Zuckerberg.)

What differentiates the Jerry cardboard cut-out is that it has already been, in effect, Instagrammed/aurificated by EIT!. They created, or exposed, its aura of empty ubiquity, of speculative existence (as in speculative economics) by collecting it ad absurdum. Dimitri Simakis, long-time member of EIT!, as well as Regional Outreach Coordinator for The Jerry Maguire Video Store, described to me a sort of epiphanic moment he had in 2016 while he was working at the “social news and entertainment company” Buzzfeed. He watched as, one Friday afternoon, a group of young co-workers, enspirited by the coming weekend, assured of what seemed an inevitable Hillary Clinton victory, as well as a general American goodness, started dancing to a Taylor Swift song. “It’s okay,” Simakis guess-paraphrased their thinking, “Obama’s president, Beyoncé has a new album, everything is okay.” And yet, as EIT! makes abundantly clear (and many of us are all too aware) everything is not okay. Empty consumerism, American positivism, and the “inclusive” celebration of a few famous black people is, along with everything, (fucking) Terrible! A single available movie at the rental store may liberate us from the perceived oppressiveness of choice, but—more to the point—it also keeps us locked to the nipple of the entertainment industry. Media engagement—whether by renting or streaming, uploading, or trolling—is a dependency (addiction) masked over by a colorful facade of “personal expression.”

Jerry an sich (Neutral Media Is Racist Media)

Jerry Maguire, like most movies (and like capitalism) is racist, misogynist, and, as Simakis told me, “anti-humanity.” “I think Cameron Crowe knew he was making an anti-humanity movie.” Simakis recounted Jerry’s antipathy toward the heartthrob toddler Ray Boyd (played by Jonathan Lipnicki) throughout the movie. Jerry shirks from touching the kid, loving the kid, and constantly side-eyes him with disdain. Likewise, his (only) friendship is based in greed and laced with racism, and his love for Dorothy (Zellweger) is tepid, at best. Defenders might claim that Jerry claiming “I’m Mister Black People” or screaming “I love black people” is a comic airing of post-racist fondness. Jerry, however, is desperate; he forces Tidwell (Gooding, Jr.) to dance for him, to be his entertainer, to be commodified into his capitalistic schema in order to reap his agent’s cut, and is in no true sense his friend. The familiar commodification of black bodies and black culture, via white exaltation of rap music, athletic prowess, and ebonics, is exemplified by Jerry’s relationship to Tidwell. And the commodification/patronization doesn’t remain within the confines of the screen. It was also reformatted for the Oscar stage.

When Cuba Gooding, Jr. boisterously whooped and clicked his heels on the stage (while accepting his Oscar for Best Supporting Actor), he was leading the way for America to accept Barack Hussein Obama. Despite the subversive “un-American” name (applying to both men), we clapped along with Cuba (during the Oscar’s audience’s patronizing standing ovation) and also recognized his volatility: he had too much stage energy, which stage-managers attempted to drown out with music. He yip-yipped, he ranted, he bounded; his energy was unrestrained. And though black men, of course, had been in the national spotlight before, Gooding, Jr.’s presence was both explicitly about race and also explicitly about acceptance itself, coming at a time when racial tensions had been bubbling anew.

The unmerited obsession with and unprecedented distribution of Jerry Maguire—three million copies of the tape sold on the first day of its release—came at the end of an era, the late-capitalist Clinton boom (boom for some) years, the last hurrah of VHS (before DVD), and the supposed national soothing of racial tensions after the violent strife (Rodney King, the O.J. trial) of the early and middle decade. The year 1996 thus heralded another transitional period, about a decade later, in 2008, when media was transitioning from DVD to digital, neoliberal capitalism had visibly derailed, and President Obama brought a message—however erroneous or eulogistic—of hope and calm to the country.

Gooding, Jr. himself thus symbolized a bridge with bi-racial appeal. His character had to literally coach Jerry through pronouncing the words, “I love black people.” And yet Tidwell’s prowess and confidence weren’t enough to win over the willingness of the market forces on their own. Jerry had to take him there.

You can smile and sing, and even be athletic, but you need to show that you can contain that energy. Obama, an athlete, and a decent singer, was accused by many of not being black enough. It’s hard to imagine the criticism, however, if he had openly displayed his “blackness,” as comedians Key and Peele exaggerated in their skits of Obama’s “anger translator.” The performance of blackness is encouraged only when it fits into the racist capitalist schema. As Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote of Barack Obama in The Atlantic, “Obama’s embrace of white innocence was demonstrably necessary as a matter of political survival.” Gooding, Jr., after wooing America with his heel-click on the Oscars’ stage, was subsequently relegated to middling roles, and fell (or was pushed) into half-obscurity, until reemerging to play the black antihero of the ’90s: O.J. Simpson, in the FX true-crime series The People v. O.J. Simpson.

In real life (however much it was media-hyped and variously filtered), Simpson’s exoneration served as the vindication of decades of the LAPD’s abuse, brutality, and oppression of the black community, though Simpson himself had distanced himself from racial discourse, holing up in the exclusive (and nearly exclusively white) Brentwood community of Los Angeles. Gooding, Jr. seems to play the role by channeling not only the celebrated, and then vilified, real-life character of O.J., but by working through his own story of being celebrated onstage for cartoonishly portraying a black stereotype in a racist film. As EIT! so exuberantly celebrates, Gooding, Jr. is the nonpareil of anti-mimesis: his role as O.J., it seems, is an on-screen exercising of his own torn past. If EIT! were directing, the series might continue beyond the O.J. trial, all the way up to the release of Jerry Maguire, and maybe, if things had turned out differently, O.J. would have snagged Gooding, Jr.’s role. The lines between actor and character, between news and entertainment, between media and marketing, have been twisted into a knot. Cue the title screen: Everything is…