Victoria Law’s new book, Prisons Make Us Safer: And 21 Other Myths About Mass Incarceration, exposes the contradictions of a carceral state that weds public safety to the violence of police and prisons. In less than 200 pages, Law explodes myths about the promise of prison reform, the root causes of crime, and the effectiveness of policing and incarceration. “Our reliance on prisons lulls us into ignoring the social, cultural, and economic factors that lead to violence and ultimately make us less safe,” she writes.

I first met Law — abolitionist, denizen of Manhattan’s Lower East Side and the author of several other books about prison including Resistance Behind Bars — through mutual friends at anarchist potlucks and book fairs. These were spaces that experimented, though imperfectly, with collective care and mutual aid beyond the state’s social order. In the early ’90s, Law was an integral part of the legendary ABC No Rio, a squat in the LES that did everything from host punk shows to run a Books Through Bars program that donated books to prisoners. Law’s work is informed by, and continues to inform, a social imaginary of community and compassion, challenging the racist carceral state’s structures of violence and social death. She has influenced how I think about all of those things, and how I understand the role of prisons.

After a year of uprisings, a pandemic that exposed the cruelty of a society built around essential yet disposable lives, and decades of movement building, the discussion of prison and police abolition has moved into the mainstream. In a shift rich with potential, these issues are no longer confined to classrooms or alternative spaces like ABC No Rio. Law’s voice affirms that we all deserve better than the current system.

Over Google Chat, Law and I spoke about the possibilities and challenges of abolition, resistance behind bars during the pandemic, and the joy of community gardens. Our conversation reaffirmed for me that prisons are neither inevitable nor permanent — they, and the system that upholds them, are more vulnerable than we think.

1. “We end up missing nuances.”

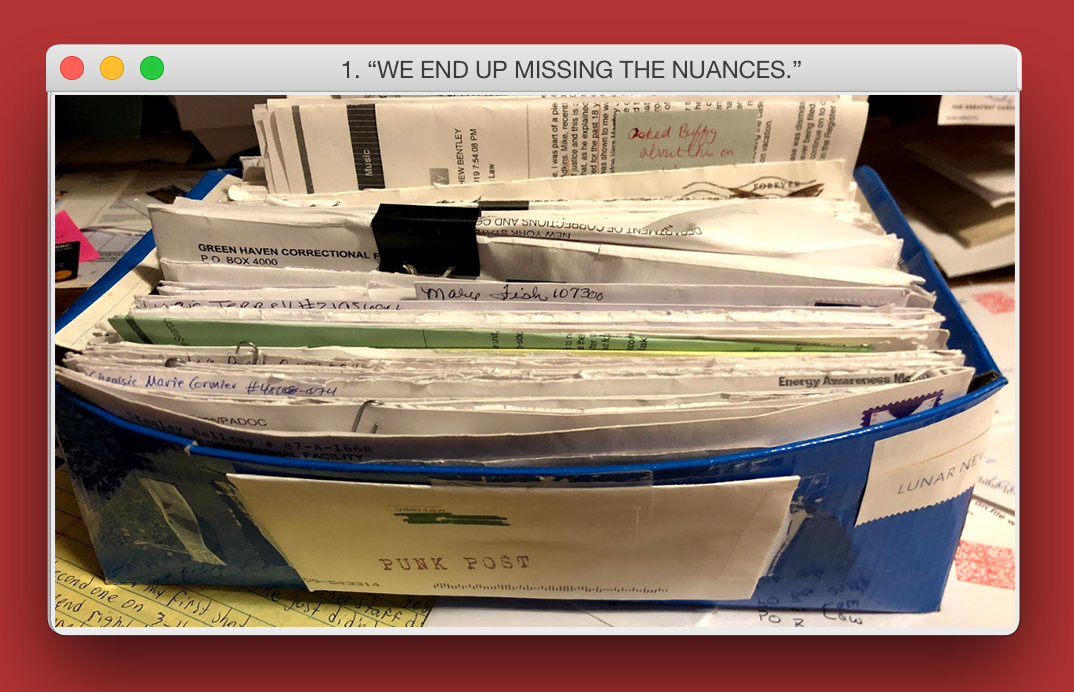

Sabrina Alli: You included a photo of unanswered letters; I am assuming they are from prisoners. How has communicating with people on the inside inspired your work?

Victoria Law: I don’t think you can accurately report on prison conditions and incarceration without being in contact with people who are inside. That said, there are many journalists who work, and stories that happen, without that communication, and they rely on prison officials’ or outside advocates’ version of what is happening. We end up missing nuances, and the perspectives of those who are experiencing day to day injustices and atrocities inside. What prisoners deem important might be different than what outside advocates or prison officials identify as the crucial issues in prisoners’ lives. What prisoners identify as important can also lead us to understand more about the long-term effects of policies like solitary confinement. There have been numerous books and studies written about solitary confinement, but in communicating directly with people, you can see its ongoing effects much more clearly than if you were to read about it in a book, a monitoring report, or some sort of study.

For example, people in solitary are strip-searched before and after being allowed out of their cell to go to rec [recreation], which consists of being alone in an outdoor cage for an hour. Women in solitary told me that when they have their period, they are not allowed to bring another tampon or sanitary pad with them. When they are strip-searched coming back from rec, they must remove their tampon and, depending on how long the officer takes to search them, bleed all over themselves. Then they have the choice of trying to re-insert the used tampon, or just bleed on themselves and their clothes on the walk back to their solitary cell. Some women, when they are menstruating, will forgo their hour out of cell to avoid this further dehumanization. I had never thought of this additional indignity until women told me this.

2. “This is how policing plays out in real life.”

Alli: Your book does a great job of unpacking the ways policing and prisons are misunderstood in our society. You entitled this photo “Revising chapter on Coney Island,” and there’s a police van behind your pages. What does this picture represent to you?

Law: That’s a chapter from my previous book, written with Maya Schenwar, Prison by Any Other Name. One summer day before COVID, when you could get on the subway and not fear for your life, Maya and I were in the thick of tossing chapters back and forth, trying to meet the book’s deadline. This chapter was about on community policing, predictive policing, and policing reforms touted as alternatives to mass incarceration, and I printed it out and took it with me to Coney Island so I could read it and put my edits in. When I got off the subway, I walked down Surf Avenue: There’s the parachute jump and throngs of people heading toward the beach, and then there’s this police van.

It shows that policing is so much a part of everyday life. When you go to the Hamptons or the Poconos, you are not going to see this same police presence. This police presence is monitoring, surveilling, and controlling the actions of people who are trying to enjoy a nice summer day on the beach, but don’t have the money to go to Fire Island or the Hamptons. This is how policing plays out in real life: Even at the beach, you’re confronted with the fact that the state could put certain people under surveillance when they’re trying to have a nice day. If you can afford a vacation to a nicer place that is not policed, where people are not marked as criminals or criminalized, you are not subjected to this. So, it really struck me. Policing is everywhere.

3. “Those are pretty crappy results, even by their metrics.”

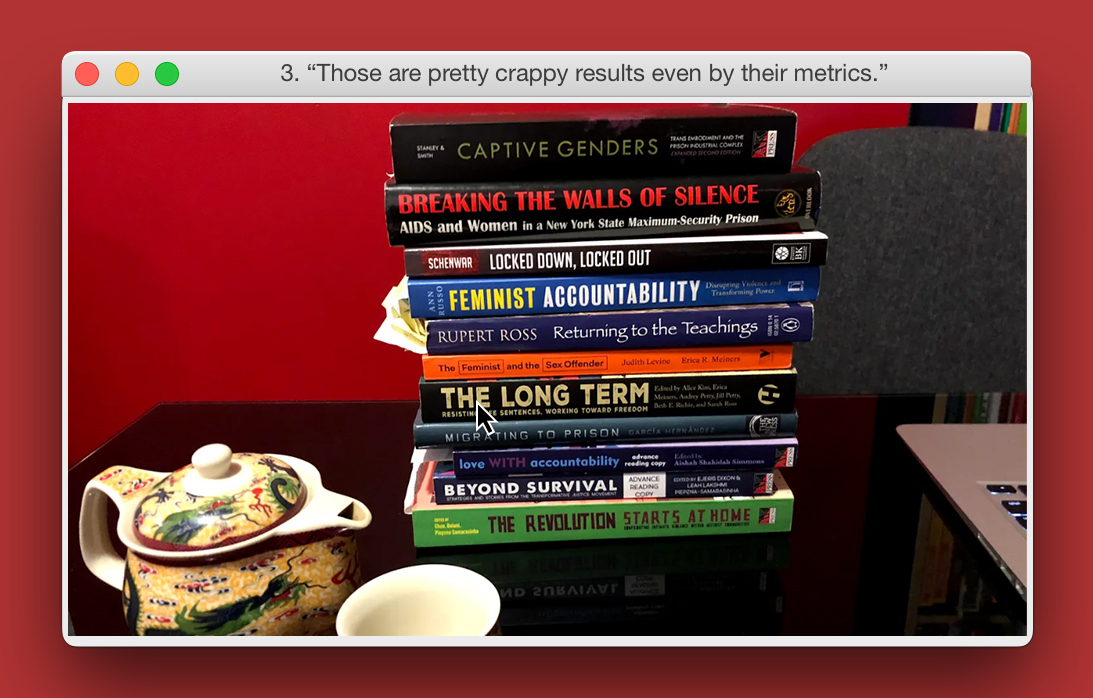

Alli: Many of these books take on the myth that being protected from gendered violence requires policing and prisons. This myth is a big barrier for many people to accept the idea of prison abolition. Tell me about how these books, and your work, untangle the myth that the state protects women from violence.

Law: First of all, we have to remember that policing and prisons come — if they come at all — after harm has been done, so police do not protect or prevent gendered violence. And people often aren’t relying on police to begin with. According to one study, out of every 1,000 rapes that occur only 310 get reported to the police. From there the numbers get even smaller: Of those 310 that get reported, only 50 lead to an arrest. Of those 50, only 25 result in a conviction. Meanwhile the survivor of sexual assault has to tell their story again and again to police, prosecutors, defense attorneys, and at trials to the jury. They have to tell it in a way that is believable and credible. They have to withstand all attacks on their personal character, their histories of sexual activity, how they dress, where they walk, and what their body looks like. None of this does anything to promote healing and safety. It doesn’t make our streets any safer. It just re-traumatizes the survivor, again and again.

Convictions also don’t do anything to help the person who committed the harm to understand why they shouldn’t have done it, or what the after-effects are. Basically, it’s a way for the state to say, “Look, we are doing something about this.” But they’re not really doing anything if for every thousand incidents only five result in conviction. Those are pretty crappy results, even by their metrics. We always hold up the threat of gendered violence, rape, child sexual abuse, and domestic violence as reasons we need prisons, but we have a nation with over two million people in prison, and it didn’t stop Harvey Weinstein from sexually assaulting women. It didn’t stop R Kelly. It didn’t stop Larry Nassar from committing repeated sexual abuses. It didn’t stop these men from taking advantage of their positions of power, because they knew they could get away with it. Prison doesn’t stop sexual assault. It doesn’t stop gender violence. So this myth that we need police and prisons to address gender-baseded violence does a huge disservice to people who are experiencing it.

And prisons themselves are sites of gender violence. The books in the picture — Captive Genders, Breaking the Walls of Silence, Locked Down Locked Out — all look at prisons as sites of violence, and what happens inside them. Captive Genders looks at trans and gender nonconforming people who are locked up, many of whom are policed because of their gender. It is so common that we have a phrase called “walking while trans,” describing people who are targeted by police not because they’ve broken any law, but simply because of their existence. The police will use any pretext to target trans people. Like, “Oh, you have condoms in your purse. You must be a sex worker.” Meanwhile any frat boy walking down the street can have a bazillion condoms with them and will not get stopped by the police or have their bags searched.

When we look at the history of reformatories, they were spaces to reform women who were seen as immoral or who were breaking the gender conventions of the day because they were doing things like getting drunk, having sex, riding in cars with boys. All of these were things women could be arrested for. Men could do those things and nothing would happen. So from the very beginning, we see policing and prisons as gendered and violent.

4. “It wasn’t like being a college student and then an intern where you make photocopies, and if you are lucky maybe they let you sit in on a meeting.”

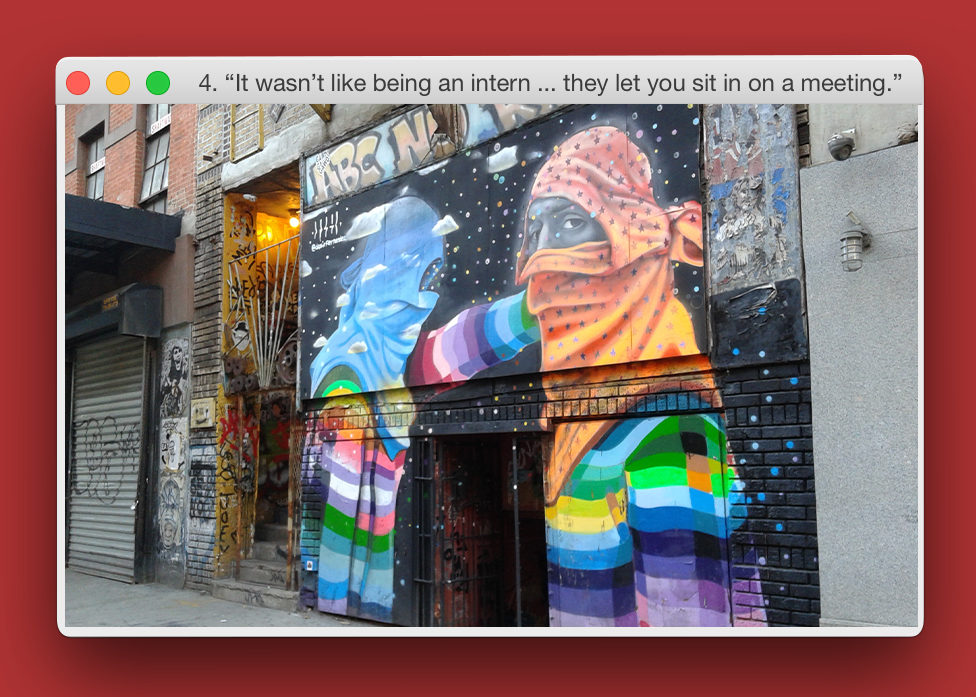

Alli: You have been a very active abolitionist, and it’s refreshing to read your work because you understand that abolition doesn’t mean just getting rid of police and prisons, but reimagining a new model for dealing with underlying conditions of violence. There are better possibilities than what we have. You’ve been very active in punk anarchist scenes, including ABC No Rio on the Lower East Side. Can you talk about this space? How does it bring together your abolitionist and feminist work?

Law: I grew up in Queens, as a child of immigrants. Like many children of immigrants I was taught that I was smart, and told that I would become a doctor or a lawyer. Those were my options. I was taught that writers are poor, so you can’t be a writer. That’s it. I was always the smart kid, but the lazy kid. If I didn’t want to do something, I wouldn’t do it. If I didn’t want to learn physics, I wasn’t going to learn physics. But if I did want to do something, I would go after it wholeheartedly.

There was no room in that narrative for learning to draw on your strengths, instead of having people push you toward things you don’t care about. Coming across ABC No Rio was an eye opener. I first got involved in 1995, during my senior year of high school. Here were people who were smart and talented — and they read books. Growing up, many of my friends who were smart ended up in gangs. They did not read books. They mocked me relentlessly for reading books.

At ABC No Rio there was an ethos of not relying on the systems that continue to fail large swaths of people. It was a challenge. That was liberating. I didn’t need to hide parts of myself the way I did when I was a teenager. ABC No Rio offered me a wider world. People could come and read all the zines we had, or learn how to do black and white photography. And Books Through Bars was there; we spent many years packing books for people in prisons until late at night. I wanted to do an art show with work by incarcerated artists; I was like 20 years old and I didn’t know anything about putting it on. Everyone was like, “Great, go for it.” I learned how to write a grant to pay the artists an honorarium. I had to learn how to write a budget and talk to grantmakers. But I was treated as capable. It wasn’t like being a college student and then an intern where you make photocopies, and if you are lucky maybe they let you sit in on a meeting.

At No Rio I also saw the different ways that people dealt with conflict. Sometimes, conflicts went unaddressed. We understood that prisons and police would not make us safer. We were not calling in the state, so we needed to figure things out ourselves, and sometimes we failed miserably at keeping people safe from harm. But the state also fails miserably at keeping people safe, as I found out early in my life. People in my family and in my neighborhood were never kept safe from harm or violence, either.

Last week the singer from World Inferno Friendship Society died. I was scrolling through all the memorials on Twitter where people wrote about how going to their shows opened up sites of possibility, and created spaces where like-minded people could congregate and connect weird parts of their lives. I remember seeing them in the ’90s when they first started playing at No Rio, and sometimes the number of people in the band would outnumber the people attending the show. I had a baby and stopped going to shows for a while, but then I came back around 2005 and 2006 and realized how big they’d gotten.

5. “She was figuring out how to make things as I was putting these books together.”

Alli: You have included many pictures of food. I’m curious about the babka.

Law: I was working on Prison By Any Other Name and Prisons Make Us Safer simultaneously. During the summer before the pandemic, my daughter got a job washing dishes at a fancy restaurant. She would watch the chef, and she got really interested in cooking. At one point that summer she made babka. She learned how to make homemade tomato sauce. She made all of this food through experimenting, and it fueled a lot of my late night revising. I needed to eat something and she would come home from work and make something. She was figuring out how to make things as I was putting these books together.

Alli: In the book, you point out that reform can occlude a larger discussion around what we actually have to do about mass incarceration. You write about how myths are fueling bipartisan reforms, and one of those myths is that if we free all the nonviolent drug offenders who are currently in prison, many people will go free. How do you respond to people who make this claim?

Law: It’s the cause most people can easily get behind, but it leaves out the hundreds of thousands of people who are incarcerated for violence. District attorneys choose to bring charges against people. Hundreds of thousands of people are incarcerated for violence. Freeing people who are incarcerated for nonviolent drug offenses will not actually reduce or significantly decrease the number of people in prison, though it might offer a little bit of breathing room for a short period of time. It’s the low-hanging fruit. And simply freeing people incarcerated for nonviolent drug offenses doesn’t do anything to address why people are using drugs in the first place, why drugs are criminalized, and whether that’s a problem. Dr. Carl Hart talks about how many people use drugs without it being a problem in their lives; the real problems are racism, poverty, over-policing, lack of opportunities, and violence. These are drivers of mass incarceration. People in middle class suburbs who are abusing drugs are not being policed or funneled into prison in the same way as poor people and people of color. Releasing nonviolent drug offenders doesn’t address any of this, or what is driving people toward violence in the first place.

If we don’t get at the underlying causes of violence or why people are being charged with violent crimes, then we don’t get to the heart of why people believe we need prisons. Most people, except for maybe Tom Cotton and other extremists, do not say we need prisons because there are too many nonviolent drug users on the street. They say we need prisons for rapists, murderers, and child abusers.

If we don’t get at root causes, we perpetuate the system. We can let out all the people with nonviolent drug offenses, back to the same shitty conditions that pushed them into prison, but how do we make sure the beds they were occupying don’t get filled up with people who have been arrested for something else? Without putting money back into community resources, we’re just going to see the funneling of people back into prisons.

Alli: We don’t have humane spaces for poor people with addiction to go. If you are addicted and poor in this country, you will be incarcerated. Most drug use intersects with other things, like mental illness and trauma. The image of the nonviolent drug offender skews our entire understanding of drug use and the root causes. So why are there so many people — nonviolent or not — incarcerated for drug use?

Law: In interviewing people who are incarcerated, I found that many of them were there for violent convictions that happened because of drug use. One woman I interviewed was named Mary Fish: With the exception of one offense, everything she was charged with was a violent offense stemming from her drug use and alcoholism. Mary was an alcoholic and then she went to prison and somebody offered her drugs. She began using drugs while she was behind bars. She’s from the Creek Nation and her family is very poor, and the US has a history of giving Native people alcohol in order to subdue them. Mary saw pills as a way to kick the alcoholism that had afflicted her, her family, and her nation. She saw that as a way out, but she spiraled into drug addiction. Her future arrests and convictions all stemmed from the fact that she was usually on drugs when she got violent. So prisons introduced her to something that fucked her life up even more.

Prisons are not rehabs; they are hotbeds of drugs. Mary had no access to places on the outside that were safe and affordable. Another woman I talked to, Susan Burton, was in and out of jails and prison-like rehabs for over a decade because of addiction. Finally her brother, who had become financially successful, paid for her to go to a white lady rehab in Santa Monica. It was a world of difference. There were no locked doors. Everyone got treated like a person. If you relapsed, they were there to catch you. She was not treated like a number or a criminal. That kind of treatment is not available to poor people.

6. “My neighbor bid a million dollars at an auction, but we didn’t actually have a million dollars so he got thrown out of the auction and the garden went to some developer.”

Alli: I want to turn to something joyful: this picture of turtles in a community garden. Where is this garden?

Law: I live on the Lower East Side, the same neighborhood where ABC No Rio is. Ruth Wilson Gilmore, who is a long time abolitionist and founding member of Critical Resistance, uses the term “organized abandonment,” and in the 1970s this neighborhood was subject to it. Capital fled. Landlords realized it was cheaper to torch their buildings to get the insurance money than to try to get rent from people. There were a lot of abandoned buildings. There were a lot of torched out lots. The people who remained didn’t want these empty lots, where garbage was piling up and people were doing drugs. And the neighborhood didn’t have any green spaces. So in the ’70s, twenty years before I even stepped foot in this neighborhood, people started renovating these lots and built community gardens. People squatted in the abandoned buildings, so the neighborhood had a vibrant and often chaotic squatting community.

In the mid ’90s real estate started to become desirable in this neighborhood, which nobody with money wanted to invest in. All of the sudden the LES became profitable and the gardens were sold at city auctions. The gardens that managed to stay did so because people put up a fierce resistance. We were not always successful, though. We lost the garden that was next to my building at the time. My neighbor bid a million dollars at an auction, but we didn’t actually have a million dollars so he got thrown out of the auction and the garden went to some developer. Now there is market rate housing there.

The garden in the picture is one of those remaining. There are about a dozen or so left, which is pretty good in a market rate neighborhood. The gardens are spaces of resistance. They were built by people who said, “We’re not going to wait for the state, the real estate developers, or the real estate board to come and give us nice places for our kids to hang out, or nice places for us to sit and have some greenery. We are going to take this abandoned lot and make it into something we want to see in our community.”

Alli: These spaces of resistance have shaped my politics and community, and its through them that I know people like you. As someone who writes about state violence, I wonder when and if writing is ever joyful for you?

Law: This past year felt particularly difficult because I was in my house writing about COVID behind bars. There was not a lot of joy and resistance in writing about people who were subject to the violence of being locked in. Along with the violence at the hands of guards or the everyday indignities, there was the added threat of a highly contagious disease that nobody knew much about. Usually, I draw on stories of resistance and resilience. If you look at my work pre-pandemic, a lot of times I’m looking at what people inside are doing or what their loved ones and their family members on the outside are doing. That’s the thing I really wanted to highlight when I went into journalism: not just the terrible conditions but the solutions. What are people doing about this? What are the stories we’re not seeing?

My first book was about resistance and organizing in women’s prisons because we weren’t seeing those stories. Maya and I end Prison By Any Other Name by considering community organizing efforts around safety and harm. What does that look like? Not just what does it look like not to prosecute people for nonviolent drug offenses, but what does it look like when you are in a community where you know you can’t rely on the police, but you also know that people are homophobic and transphobic? How do you find safety? What do you do when someone’s been sexually assaulted? One Million Experiments, the Bay Area Transformative Justice Collective, and Creative Interventions are all examples of efforts to help communities address sexual harm without depending on the police.

Even during the pandemic, when I was sitting by myself in my house hearing all these horror stories and getting mail from people in prison asking for information about the virus, I wrote about how people are surviving. People are resisting in whatever small ways they can, even if it might not seem like resistance to the outside world. To share information in a space like prison, where you are not allowed to share even a pen or a flyer, is an act of resistance. It’s the stories of resilience and resistance that make it worth it.