“Because all I did was read a story,

then retell it on this page.”

—Diannely Antigua, “Immigration Story”

“Hola, todos.”

Gloria, Vanessa Guillén’s mother, is in the corner of a busy street, holding a press conference. Her hair is in a bun on the top of her head, and she’s wearing a black shirt. Her hands are full: with her left, she holds a poster that shows a missing person report, alongside #FindVanessaGuillen and Help us get her home! in purple marker; with her right, she holds a Fox 44 News microphone that she occasionally speaks into, her mouth moving behind her bright blue mask. Her voice is gentle, steady. Her eyes continue to shift from the audience in front of her to the poster that she’s carrying: her hija, her Vanessa, la soldada desaparecida.

From June 10th to June 15th, local news channels cover Salma Hayek and her mission to bring awareness to a soldier’s disappearance. Around the same time, I begin seeing Vanessa’s face on Instagram: my explore page shows a young woman in her uniform, the front of her patrol cap a blank canvas—she must have taken this when she was a PVT, I think, noting the time between her promotions—her background the American flag. She’s staring directly at the camera. A soft smile is playing at the corner of her lips. I can imagine this picture, before it became the symbol of her disappearance (and of the military’s failure to protect her, and, later, to keep her family informed), in a frame in her family’s home in Houston, only three hours from Fort Hood, where she was stationed.

Soon, my Instagram home page begins to fill with Vanessa Guillén, bright against a backdrop of other people’s anniversaries, birthdays, home renovations. There is commentary interwoven with emoji of broken hearts and crying: “This is so sad,” “Her leadership failed her,” “#FindVanessaGuillen.” When I repost her photo on my own story, a friend, a woman married to a soldier, sends me a direct message: When I was at Bragg, a female soldier went missing.

In Fort Riley, my first duty station, I used to walk to a gym half a mile from my barracks. I had learned about it from someone I graduated AIT with—an older male soldier, who, during my second day in Kansas, had invited me to a club in one of the towns bordering the base and introduced me to a few sergeants from his platoon. (He connected better with them because they were around his age, he’d explained.) I had not yet learned how to interact with higher-ranked soldiers outside of a training environment, where they expected us to stand at parade rest and speak only after being spoken to. When these male sergeants extended their hands to shake mine, one rubbed his thumb over the top of my hand, marked with a large X (I had turned nineteen a week before I left my home state, California, for Kansas), and asked how old I was. I remember my friend mentioning that he was an E7. When I stood at parade rest to give him a reply, he cocked his head to the side—I can see now that he was confused, but he didn’t correct me. Instead, he sat down in front of me and presented me with an open sleeve of individually wrapped mint-flavored gum and asked if I wanted one.

“No, thank you, sergeant,” I said.

“Well, do you mind giving me one?” he asked.

He told me to unwrap one for him, even though he had been holding the sleeve that entire time. When I didn’t reply immediately, he continued to stare at me until I said, “Roger, sergeant.” After I unwrapped the piece of gum for him—neatly undoing the folds, one by one—he told me to put it in his mouth. He didn’t wait for a response or a reaction: he opened his mouth and put out his tongue, ready to receive what I had in my hand. My friend, the one who had brought me there, smirked before leaving to get a drink from the bar. I don’t remember much of the rest of that night. I blocked it out of my memory.

I used to walk to that gym because I didn’t know where the other gyms were. The setting sun served as my signal to get ready—I hated working out in broad daylight, even though this particular gym was indoors, on the second floor of a building that required ID cards for access. The sidewalks were well-lit, but I saved time by cutting through shadowy parking lots. I only occasionally called someone on my phone to talk to me on my way back home, even though I went there every day during my first few weeks.

In 2004, then-Secretary of Defense Donald H. Rumsfeld appointed Dr. David S. C. Chu to review the Department of Defense’s process of treating and caring for sexual assault victims in the military. The Sexual Assault Prevention and Response (SAPR) program was introduced in 2006, with each branch training a SAPR officer, a point of contact. The Army’s SAPR program evolved into SHARP: Sexual Harassment/Assault Response and Prevention. Today, looking at its website, you would probably think that it’s an efficient program, boasting a concise list of goals and resources, acronyms that are supposed to provide both a sense of comfort and urgency to its readers: Sexual Assault Response Coordinators (SARCs), Victim Advocates (VAs), Healthcare Providers (HCPs), sexual assault forensic examinations (SAFEs), Military Rules of Evidence (MRE), National Advocate Credentialing Program (NACP), Department of Defense (DoD) Sexual Assault Advocate Certification Program (D-SAACP). Everything’s categorized, straightforward, clean. Our Mission: Enhance Army readiness through the prevention of sexual assault, sexual harassment, and associated retaliatory behaviors while providing comprehensive response capabilities; Our Vision: An Army free of sexual assault, sexual harassment, and associated retaliatory behaviors.

When filing a complaint, though, the options branch out into more options, and the process becomes more labyrinthine. Sexual harassment or sexual assault? Informal or formal? Restricted or unrestricted? Military or civilian? I was always confused by the vagueness of some of these options. If the victim were to file a restricted report, allowing them to receive medical treatment, advocacy, legal assistance, and counseling, but not triggering the official investigative process, the assailant would remain unpunished and a military protective order would not be an option to give. To change a report from restricted to unrestricted would trigger an investigation, but may also result in “significant obstacles” such as “lost” crime scenes, a result of its previous restricted status. While a restricted report can become unrestricted, an unrestricted report cannot become restricted.

The SARC, the trained soldier responsible for handling these cases, is at the center of this web. They’re the advocate, the subject-matter expert, the go-to person. In a perfect world, in a perfect Army, there would be no question about the reliability of the SARC.

I take that back.

In a perfect world, there would be no need for a SARC.

Last night, I had a FaceTime conversation with one of my closest friends. Our last names ensured that we were going to be in the same platoon in our AIT company. It had been three of us—me, her, and another young woman who is also now out of the military (triplets, our platoon called us)—walking up and down Fort Sam Houston, stealing other peoples’ taxis at the corner shoppette. When I called her and she picked up, she sighed before saying, “Cuepo.” Her son was in the room, she said, and she introduced us to each other—him shying away and into his mother’s arm; me trying to barter: a “hello” from him for a view of both of my dogs. “Doggie!” he said, squealing when I flipped the camera to Jaxon, my Husky-Shepherd mix. “He’s so cute!”

After he went back to his iPad, my friend turned the camera back on herself. We just stared at each other.

“We used to walk alone everywhere,” I finally said. She said, “I know.” We had been typical eighteen-year-olds, fresh out of high school, in a world that resembled college: we were fun, fearless, flirty. Whenever we caught up with each other nostalgia would hit us and we would start talking about the same old escapades, as if we were still in Fort Sam Houston: “Remember when he tried to get into the taxi?” “Remember when we had to put our PTs over our jeans?” “Remember…?”

This conversation went the same way, but with a more somber tone, tinged with sadness and frustration. We echoed each other’s words: How could her leadership have lost her? How could they not have looked for her harder? How could they not have torn the place apart, locked down the base, questioned everyone for her?

We talked more about life after we parted in Fort Sam, after we arrived at our first duty stations as lowly privates, trying to prove our worth to our receiving units. The word “alone” heavy with meaning: It could have been me. And, when we talked about becoming sergeants: It could have been one of my soldiers.

“Her mom,” I said, and again, she said, “I know.” Our mothers had been the heads of our households growing up—another common thread—and we always talked about them. Her mother was our mother, a woman who had never sent a child to the military, but who trusted its promises of care and security nonetheless.

“¿Dónde está mi hija?”

“Yo necesito respuestas.”

“¿Qué pasó con mi hija?”

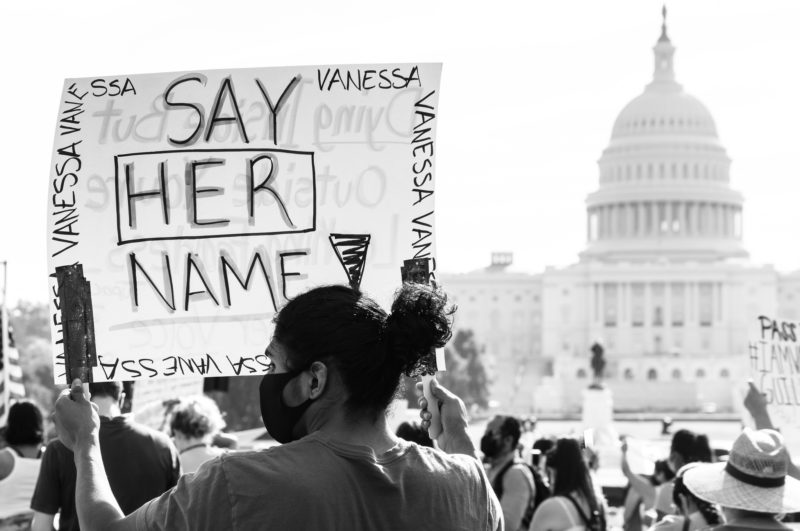

Gloria is challenging everyone: the reporters, the spectators, the military. She is asking the same question she had asked months ago, before the hashtags, before the celebrity attention. Behind her, one woman raises a poster: Bring Vanessa home! Her questions and statements continue, as if the vehicles in the background that are revving their engines—a cruel ploy to distract her and overpower her voice—don’t exist.

On the news they cite a Pentagon report documenting a rise in sexual harassment and assault. Four years ago, the numbers had decreased. Now, in 2020, the estimated past-year prevalence of sexual assault has increased again. Publications use “sharp” as the adjective to describe the sudden jump. It’s a rollercoaster ride of numbers and percentages, these dips and rises, against a backdrop of the DoD’s efforts to advance a “military culture free from sexual assault.” Efforts that say: “Our reaction is at a level that should be appropriate enough to give us allowance over these fuck-ups.”

Vanessa Guillén was born on September 30, 1999 to Rogelio and Gloria Guillén.

Vanessa Guillén had two sisters, Mayra and Guadalupe “Lupe” Guillén.

Vanessa Guillén joined the Army in June 2018.

Vanessa Guillén went missing on April 22, 2020.

Rewards for information regarding Vanessa Guillén’s disappearance climbed from $5,000 to $50,000 in a matter of weeks.

Human remains were found on June 30, 2020; two days later, they were confirmed to be Vanessa Guillén.

Vanessa Guillén was twenty years old.

The screenshots of the criminal complaint and the news coverage show that Vanessa was reported missing by her unit on the 23rd of April. She had left her arms room to visit another one, controlled by SPC Aaron Robinson, leaving behind her belongings for what was supposed to be a short interaction. On the 28th, USACID interviewed Robinson, who denied seeing Vanessa after their encounter in his arms room, using his girlfriend, Cecily Aguilar, as an alibi; later, Aguilar would agree that he had been with her all night. On the 18th of May, two interviewed witnesses said that they saw Robinson taking a tough box out of his arms room on the night of April 22nd, his work spilling into the early morning of the 23rd. On May 19th, a phone search showed that Robinson had called Aguilar multiple times throughout the night of the 22nd and the 23rd of April, contradicting his previous statements that he had been with Aguilar at around that time. Later, Aguilar gave a different version of events: she had taken a long drive with Robinson to “look at the stars” at a park in Belton, Texas; analysis of cell phone data would pinpoint the location along the Leon River. A closer look into the area would reveal a burn site, where the remains of a plastic tote or tough box would be found close to where Robinson’s phone had “pinged.” On June 30th, contractors working on a fence adjacent to the river would discover scattered human remains “placed into a concrete-like substance and buried.”

Robinson had bludgeoned Vanessa in his arms room. Aguilar had conspired with him to mutilate and hide Vanessa’s body. The Guillén family’s lawyer, Natalie Khawam, told CNN’s Kay Jones and Ray Sanchez that the family believed Vanessa “had planned to file a harassment complaint against Robinson the day after she was killed, and that they believe Robinson became enraged when she told him that.”

I think now about SHARP’s mission and vision. Protection against retaliatory actions was something that it had promised victims, too.

The 2019 Department of Defense Annual Report on Sexual Assault shows an increased number of sexual assault reports by service members for incidents that occurred during military service in FY18. An estimated 20,500 service members experienced sexual assault in the past year—a “statistically significant increase” from FY16.

“Sexual assault in the military occurs most often between junior enlisted acquaintances who are peers or near peers in rank,” the 2019 DoD report says. In its conclusion, it reiterates this point once more: “Survey data also indicate that perpetration for sexual assault and sexual harassment is most often within the E3 to E5 rank. Alleged perpetrators are often the same rank, or slightly higher, than the victim.”

A SHARP Foundation Course takes eighty hours to complete; a SARC/VA Career Course seven weeks; a SHARP Trainer Course twelve weeks. Soldiers are required to participate in annual unit-level SHARP training sessions; commanders are required to ensure that each soldier’s training record is up to date.

What does this mean to the victims? To their families?

Before we said goodbye, my friend told me that she’d had problems with sexual harassment before, but couldn’t report it.

“Why?” I asked.

“Because the man who did the harassing was the SARC.”