The air conditioning was cold, and out the tinted windows of the rental Chevy, heat waves shivered across the furrowed fields, the stalks browned with October but the bolls swollen, wisps of cotton bursting free like torn feather pillows. Here was the catfish plant puffing steam from twin chimneys, and then the city sign, “Welcome to Promise,” and it all seemed exactly the same, even to the dusty Ford doing twenty under the speed limit that I came on and got caught behind, even to the driver’s helmet of blond hair and then, as he craned his head about to see me, the stare, disbelieving and irate, as if to say, “Chinaman, you know you don’t belong.” Yes. Back in the Delta, indeed.

It had been four years since I’d taught here as a Teach For America volunteer; now I was back to speak with this year’s corps. I’d thoroughly rehearsed my talk about the opportunities they’d have to change children’s lives. I would speak of Serenity Warner, who came to my classroom reading at fourth grade level and left at an eleventh grade level and who’d won the school Reading Contest by a wide margin. “You will alter a child’s horizons,” I’d declare. “Change a child’s future. What you do in your classroom matters.”

Now, the familiar run of the highway strip, the Double-Quick and Conoco and Waffle House, the Grace food store. Black people milled about parked cars, heads down, shielding their eyes and noses from the dust of passing cars. The buildings were low and squat, cinder block and brick, except for a few structures that favored rust-browned tin. I glanced at my watch and saw I wasn’t due at the school for half an hour—plenty of time to drive the familiar routes. At the next light, I turned onto Main: the two-story colonials with wrap-around porches, the magnolias with trunks like castle turrets. Sidewalks baked in the sun but nobody was walking the lonely false-fronts of downtown, the windows boarded and dark in the gutted center. And then the bump of the tracks and the black side of town, the eyes of old men and women staring from the shade of rusting roofs, perched on porches sagging to the dirt yards: Felicity Street.

Every afternoon, I’d taken children home through these dusty, potholed streets, and I looked now for the kids I’d taught, though they’d be older and who knew if I’d recognize them at all? Children turned to point from the side of the street, and I did not know them, but I looked anyway for recognition in their eyes and found only fascination at an unfamiliar car. I searched for landmarks, found them readily: Lashawn’s house, nobody outside I could see. Ms. Mason’s place, better kept than the rest, the siding new, the lawn almost green. And then I came to Serenity’s house and stopped the car, stunned.

The porch, front door, and the left side of the front wall were still there, burnt black and umber at the edges, but the roof was gone, everything but the frame taken to ashes and rubble. I pushed out of the car with it still running, hurried up as if there was something to be done, and stood in the still air with the motor chugging behind me and the sun beating down and all the ruin before me, and there was nothing there to reveal what had happened.

Serenity loved reading more than any other student in my class. She wasn’t the fastest reader or the brightest student—that honor was reserved for Felicia Jackson, my evil genius. The difference was that Serenity loved reading, loved books in a way I could never quite get my head around. She was from a family who was the kind of poor that made the baseline poverty of the rest of the children in my class seem first world. Serenity’s uniform shirts were spotted with bleach stains and grease stains; often she smelled a sour, intestinal scent of body, though it was hard to say if that was because she hadn’t showered or her clothes hadn’t been washed. Her ill-fitting khaki pants were bunched at the waist where they were held by a fraying woven belt. The fabric was unraveling at the bottom where it appeared to have been scissored short: a larger hand-me-down cut to length but not to size. One pair of her khakis had holes at the pocket-line, and though Serenity went to lengths to hide them, sometimes a view of her cotton underwear was evident. More than once, I’d caught a child snickering or mocking her and had pulled them into the hall and lectured them as to the shame of such cruelty. Serenity handled herself well with the insults: she ignored them. Only Felicia, with her talent for finding vulnerability, could get to Serenity, whom she called “Raggedy Serenity” and “Ragdoll” and “Ser-nasty” and “Garbage-girl.” These insults only worked once, when Felicia first deployed them; the other children picked them up, but by that time, Serenity was hardened against them.

Perhaps this harassment was the reason Serenity loved so much to read: in books lay sanctuary from the unpleasant present. She made my classroom by seven-thirty each morning, after dropping her little brother Terence off at his third grade classroom. She greeted me with a measured smile and a wave, and immediately barricaded herself in beanbags at the corner behind my desk and opened her book. She kept a book at her desk, and our agreement was that she could read the moment she finished her work, so that mostly she was reading. She gave me her book to hold during lunch so she could read at recess, where she’d either stay near me so that I could keep the other children from harassing her, or sit with her back at the corner of the fence so as to be able to see the other children coming.

Serenity was from a family who was the kind of poor that made the baseline poverty of the rest of the children in my class seem first world.

After school, she fetched her brother from the lower school and stayed with me for as long as she could—often until six or seven o’clock in the evening. She kept an eye on Terence, who was a bundle of energy and angst, a pain in the ass for me to manage, though I let him stay anyway. She was careful, too, to find a place away from Felicia, who often stayed with me afternoons talking and helping to clean the classroom and prepare for the next day. Serenity had, she said, “nothing to go to”—she was solely responsible for Terence through the evening, and no adult ever checked on her. When asked where her mother was, she’d shrug and say quietly, “Somewhere.” I’d asked around and found that the word among the children was that Serenity’s mother was “always messed up,” and that she “do all kind of nasty thing for men for money.”

For the amount of time she spent with me, I had surprisingly little rapport with Serenity. It wasn’t for lack of effort: I’d go to her when she was reading and ask questions about her latest book, and her answers revealed a passion for the fantastic. She liked to be carried away into a world with new rules and possibilities, these realms of fantasy and magic and inevitable happy endings. “Them wizard children, they got the spells and smarts to make all that evil go down,” she’d say. “They face they trouble and find an answer, always.” When I praised these connections, told her what an excellent reader she was, she thanked me, impatient to return to the book. And so, mostly, I let her read.

I often took her and Terence home after school, especially if it was dark. Their place was an eyesore in a neighborhood of aging shacks and tin-roofed hovels. The walls of the house were green with decay, the windows had been sloppily boarded, and the roof was covered with mismatched sheets of plastic. The dirt yard was filled with food wrappers and empty beer cans tossed in at the invitation of the bags of garbage piled there to head-height. The smell of rot was gagging even from the car. Serenity would thank me, take Terence by the hand, and stride into that yard past the hill of garbage without looking back.

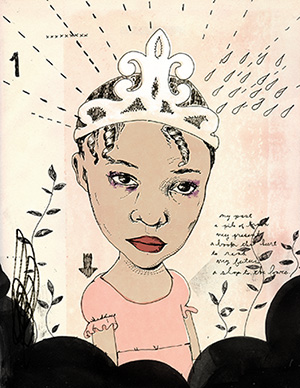

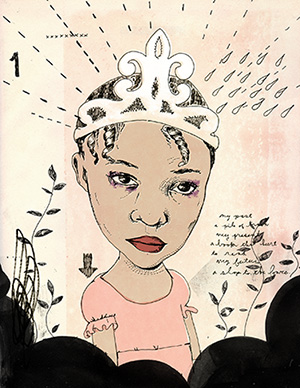

The last Friday of each month was “Dress for a Dollar Day” when the school relaxed its dress code as a fundraiser, allowing children who paid to dress down. Suddenly, the sea of uniforms would give way to color and outlandish style—boys in basketball jerseys and cargo shorts and impossibly white sneakers, girls in pleated dresses and mini-skirts and jeans with the cuffs folded, in heels and striped blouses of purple and blue and green. It was dizzying. Though nearly every child in the school was poor, most dressed down, their parents finding a dollar for that one day of self-expression. Serenity never dressed down—not until the last Friday in February. Serenity hadn’t arrived early like usual, and it was five minutes to the bell. I was at the board and so I didn’t see her enter, just heard the clamor of the classroom go suddenly silent. I looked up, and there she was.

The dress was terrible. Where she found it I cannot imagine, not with its awful pink velvet, the ruffled sleeves, and neckline looped with lace, its bell-shaped, formless fall past the hip. It was timelessly bad—perhaps handed down to her mother from the turn of the century, perhaps purchased at the local thrift store. It was the sort of dress that you might imagine in a fairytale kingdom, which was, it seemed, Serenity’s desired effect, for she wore on her fresh corn-rows a plastic tiara studded with sequins and glitter. Worst of all was the makeup that she looked to have applied herself: heavy violet and green eye makeup that gave her eyes a bruised, sunken appearance, caked mascara, burgundy lipstick that clashed with everything else and made her lips seem painted on. She took a step toward me, smiling, and swayed on four-inch clear plastic heels. My first impulse was not to stifle laughter, but to cover her with anything at all I could find. I forced a smile, but before I could say anything, Felicia’s voice rang out: “Jackie, what are you wearing?”

Serenity took two steps toward Felicia with her chin lifted in defiance. “Today I’m a princess,” she said.

Felicia opened her mouth to say something, saw the warning on my face, and let her mouth close. “I think you look—lovely,” I said.

I was at the board and so I didn’t see Serenity enter, just heard the clamor of the classroom go suddenly silent. I looked up, and there she was.

Somehow, we all made it through that day. I can still picture the lunchroom, everyone turning to stare, the snickers and laughter and the stricken expressions on the faces of the other teachers before they hushed their classes. I remember the lunch lady, who always made me a double plate of catfish and hush puppies for the normal price, pulling me aside and saying, “Ain’t you gon’ send that girl home?”

“No,” I said, refusing to explain. And I still don’t know that I can explain, for Serenity was nothing if not observant. She knew by the end of the day that everyone in the school thought her outfit laughable. She may have known even when she put on that dress and finished with her makeup in her mother’s mirror. What I know is that Serenity wanted that day to appear as close to a princess as she could style herself, and she knew exactly what she did. It was not in me to deny her what her dollar had bought.

A week later, I did a unit on poetry—on the theme of past, present, and future poems. I read Serenity’s over her shoulder:

My past a pile of trash

baking in the sun.

My present a book

that hurt to read.

My future a slap to the face.

I stood, stunned, then bent over her desk. “Is that really true, honey?”

She put her chin to her chest and said nothing. Finally, I saw she was staring at my silk tie, which had fallen across her hand. “Sorry,” I said.

“That—okay.” She folded her hands on her desk.

“But—your poem, Serenity.”

She turned to stare out the window where the day was blindingly bright. Her voice was small and quiet. “It just some words. Don’t you worry, Mr. Copperman. I just like the way it sound.”

I put my hand on hers. “Well, Serenity, I like the way it sounds, too.”

She met my gaze—something she rarely did. There was a defiant firmness in her eyes, the recognition of something vast and awful that she faced with as much dignity as she could. “If it sound good, then I guess it a good poem.”

I could think of nothing to say, so I stood, my hand touching hers, and thought of the story she deserved. I tried and tried, but could not picture the happy ending.

I walked the ruin of Serenity’s house. The fire was old, the ashes and soot dusted over and washed out, so that when I touched the burnt support beams they barely marked my hand. I found the metal frame of a bed, the coil of springs half-buried in dirt, here a burnt can or picture frame or oven rack, indistinguishable shards of glass that might have been beer bottles or cups or bowls. I pictured the house as it had been, imagined the flames eating it from within. It would have gone up quick—those old, dry boards, already part air. Through the standing frame there were now patches of sky, the shiny leaves of the neighbor’s magnolia, my rental car still running. Everything was open.

She put her chin to her chest and said nothing. Finally I saw she was staring at my silk tie, which had fallen across her hand. “Sorry,” I said.

I’d made Serenity into a success story: the girl from the poor family who made good on the opportunity of my classroom. In my telling, I’d reached her, lifted her from her small circumstances into a bright, boundless future. I’d made her an anecdote and so forgotten her.

In this windowless house, Serenity had huddled reading of a different world, dreamt herself in a different life. It was easy to picture her trapped by the rising flames, facing her fate like a heroine, chin held high and proud, confirmed in the end she’d always known was coming.

When I reached the school, I asked my principal what had happened. No one had died in the fire. The family had left on a bus, and that’s all anyone had heard.

When I consider Serenity now, I recognize how little I know and take comfort in that uncertainty—she could be anywhere at all. Then I picture her the night of the fire, watching the flames consume everything she’s ever known. Finally, she turns her back to the heat, stares into the surrounding dark, and believes, for the first time, in escape.

Michael Copperman teaches writing to non-traditional and at-risk students of color at the University of Oregon, where he received an MFA in Fiction. His writing has or will appear in The Oxford American, Best Creative Nonfiction (Norton Anthology, vol. III), The Oregonian, The Arkansas Review, and 34th Parallel. From 2002-2004, he taught fourth grade in the rural black public schools of the Mississippi Delta.

To contact Guernica or Michael Copperman, please write here.

Illustration by “Dewey Saunders”: www.deweysaunders.com