Whether scrutinizing the abuses of solitary confinement in a Pennsylvania prison, the day-to-day realities of life in a Syrian refugee camp, or her own personal and political experiences, writer and illustrator Molly Crabapple captures what she sees with conviction.

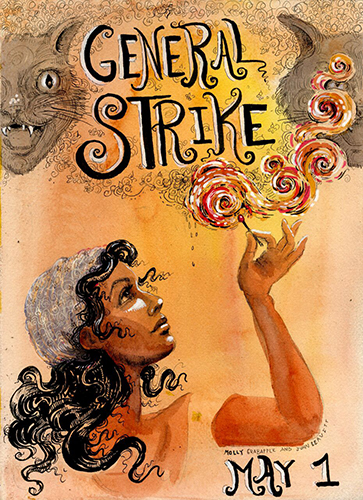

Formerly the house artist for the infamous New York club The Box, Crabapple’s distinctive political illustrations became a staple of Occupy Wall Street. Invigorated by the protests taking place right outside her apartment in Zuccotti Park, she drew a poster of a malevolent top hat-wearing “vampire” squid—using journalist Matt Taibbi’s metaphor for “rapacious banks”—which she shared on her Tumblr, encouraging followers to “stick [it] on everything.” (In 2014, she would provide the cover art and illustrations for Taibbi’s book The Divide: American Injustice in the Age of the Wealth Gap.) Her poster for the May Day General Strike of May 1, 2012, which depicts a woman lighting a match, is now in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art. Rolling Stone has called her “Occupy’s greatest artist.

In her new memoir, Drawing Blood, Crabapple reflects on her work as an artist, journalist, and activist. The book offers wide-ranging and incisive critiques of the United States’ criminal justice system and the global financial industry, and contains Crabapple’s reporting from Guantánamo Bay and Syria for Vice. “If there’s a theme in my work, it’s that I like to focus on smart people who are facing oppression, and who are fighting back against it,” she says in the interview that follows.

Crabapple says her 2011 series of paintings, Shell Game—intricately detailed depictions of the crises and revolutions that took place around the world that year—were what made her into a writer. As she explains in Drawing Blood, completing each image involved traveling, observing, researching, and interviewing. “With each painting, without even knowing it, I was learning a skill I’d told myself I wasn’t good enough to attempt,” she writes. That was in 2012. The following year, Crabapple was reporting.

Reviewing Drawing Blood for The New York Times Book Review in December 2015, Deb Olin Unferth observed: “The book reads like a notebook of New York, a cultural history of a certain set. Filtered through her eyes, we see 9/11, the aftermath of the crash, Occupy Wall Street, Hurricane Sandy, and onward…. [Crabapple is] a new model for this century’s young woman.”

I met with Molly Crabapple in November in her New York City apartment, which doubles as her studio. We discussed the power and possibilities of subjectivity in journalism, the specific experience of being a female reporter, and why neutrality and boredom are weapons the state.

—Sarah Galo for Guernica

Guernica: In Drawing Blood, you write about wanting to get away from your childhood: “Being a child meant having no control over my life.” You’ve also written, in an article for Vice, you wrote: “Innocence is a relic of a time when women had the same legal status as children. Innocence is beneficial to your owner.” Do you see the constraints of childhood as being similar to the constraints of innocence?

Molly Crabapple: I hated being a child because to be a child means that you are essentially the property of your parents, benevolently or not. You have no control over your life. You can’t even go to the bathroom during class in school without raising your hand and talking about your bodily needs. You’re controlled at the most intimate level as a child, and every fucking part of me bristled against that.

Innocence is always the state of being untouched, right? Sometimes it’s synonymous with virginity, so sometimes it’s quite literal, but sometimes it’s more of a mental state of being untouched, of not having seen a lot of the world. Fuck that. What on earth could possibly be the point of making someone’s virtue reside in what they haven’t experienced, in what they haven’t done?

I think it’s very telling that when virtue was spoken of in the classical sense, for men, it always meant bravery or protecting others or being an adventurer and going out into the world—whereas a woman’s virtue meant keeping her legs closed. What a horrifying concept, that you start in some sort of state of nullity. You start like a white blanket and you have to preserve that, and each year that you live chips away at your essential value.

How do you fucking get up, walk down the street in a woman’s body, and not be aware of all the violence around you? You just do it anyway.

Guernica: A lot of your work essentially involves speaking truth to power, so the threat of violence is often lurking in the background. How does gender relate to this?

Molly Crabapple: We live in a violent world. I mean, how do you fucking get up, walk down the street in a woman’s body, and not be aware of all the violence around you? You just do it anyway. I don’t know even know how one thinks about navigating it. It’s like, how do you navigate a world where you might die in a car accident at any point?

Guernica: In 2012, you and journalist Laurie Penny traveled to Greece and covered the crisis in Athens in a gonzo journalism-style e-book called Discordia. Do you see your writing as part of the gonzo journalism tradition?

Molly Crabapple: I actually always have a debate about whether I want to put myself into it. Lately, I haven’t been putting myself into my work that much, because I’ve just found the stories of the people I’m talking to much more interesting than my reactions to them. But I also think that, for what I do, I can’t reasonably pretend to be a transparent and omniscient narrator who brings no personal perspective. That person doesn’t exist.

Guernica: In your piece on a Syrian refugee camp for Vice, you noted there are people who come to Syria to volunteer, and then there are the journalists who say, ‘Oh, I was here for a day’—and you add, “Myself included.” When you do place yourself in the narrative, it seems you are careful to acknowledge your limits.

Molly Crabapple: Exactly. The thing that I hate is that Nicholas Kristof style of writing where it’s like, “I saw the poor, they made me so sad. What can I do about sadness? I am so brave.” It’s just like, shut up, man, shut up.

Guernica: You also included yourself in your story about Hebron, where you mentioned your privilege as an American journalist. It was a way for you to reveal a fuller picture.

Molly Crabapple: The occupation is really terrible on a variety of levels. It’s terrible on the “shooting people and torturing people in prison” level. But I think the thing that is very hard to convey is that it’s also this bureaucratic grinding-down and daily humiliation that I think would probably be as horrible as the spectacular violence. I don’t want to say it is more or less horrible, but it involves your life constantly being at the whims of these fucking teenagers with AK-47s who hate you.

That’s so much of what makes laws or states horrible. It’s not just the spectacular violence; it’s the violence of these laws that twist human life and affect people on an intimate level. But these laws seem legitimate because they’re put in this legal language. For instance, the laws in Hebron would never say, “We’re gonna force people to enter their houses through the roof.” Instead, the laws say, “There were street closures for security in Zone A.” That sounds neutral and rational. Neutrality and boredom are the weapons of the state.

Guernica: Do you think this neutrality can seep into journalism as well?

Molly Crabapple: Oh God, absolutely. A lot of things sound neutral, but they’re not. A typical example would involve police violence. It’s usually forbidden to call police “murderers,” even if they’re convicted of murder. People will say that it sounds hysterical and unobjective. Whereas if there was any other person who was videotaped strangling someone to death on the street, you would call them a murderer, probably even before they went to trial.

The Eric Garner case provides an apt example. There are two descriptions that you could offer. One is: “Police Officer Daniel Pantaleo choked Eric Garner to death.” The second one is: “Eric Garner died during an arrest,” or even, “Eric Garner died, during an arrest, of a blocked windway.” The second set uses the grammar of the passive voice to make it so that a police officer isn’t killing him, it’s just that he died, somehow.

Guernica: In Drawing Blood, you describe how ideas of objectivity and subjectivity function in photojournalism and in your art. You write: “I found that drawings, like photojournalism, could distill the essential. Unlike photography, though, visual art has no pretense of objectivity. It is joyfully, defiantly subjective. Its truth is individual.”

Molly Crabapple: Well, photos are still considered proof. Despite everything we know about photo manipulation, a photo is still considered an objective document. You can’t use a drawing to prove a war crime. A drawing doesn’t have that notion that it’s proof of a reality. Because of that, you can do all sorts of interesting things in it. I recently saw an exhibit at the Bronx Documentary Center of what I can only call the fuck-ups of photojournalism. It showed how all these different famous photos had violated the ethics of photojournalism. I was like, “I do that shit all the time, man!” Of course I change what colors are like; of course I would make some things more saturated or desaturated, or do all sorts of things to change the visual drama. I thought, “Thank fucking God I’m a visual artist. I have so much more freedom than these guys to make a picture.”

Guernica: Your writing is marked by a similar sense of conviction. Did that arise from being an outsider—an artist—rather than a journalist?

Molly Crabapple: Absolutely. I think it would have been much harder for me if I had just wanted to be a journalist and tried to break into it with this sort of voice. I came in as an established artist. People were hiring me for what I did and for who I was. I think that has given me a vast amount of leeway; I feel so lucky that I came in that way.

If there’s a theme in my work, it’s that I like to focus on smart people who are facing oppression and who are fighting back against it.

Guernica: One of the best examples of your journalistic voice is in the piece where you write about confronting Donald Trump over his company’s labor practices in Dubai.

Molly Crabapple: I was the only person that said anything [critical]. Fuck that guy, man. He’s the fucking fascist underbelly come to life. And you know what’s funny? So many people have said to me, “I like Donald Trump because he just says what he thinks, he doesn’t give a shit.” This is essentially the appeal of other people like Putin, Netanyahu or Erdogan. Besides, it’s the appeal of fascism: it’s replacing where your political thinking should be with a sexual fantasy of someone who’s big, strong, and tells you what to do and doesn’t ask a lot of questions.

If there’s a theme in my work, it’s that I like to focus on smart people who are facing oppression and who are fighting back against it. For instance, when I did my Abu Dhabi piece, Ibrahim, the young construction worker in the piece, was such a smart dude. He was living in a world where everyone is shitting on him because he’s a blue-collar Pakistani guy. This was a guy who risked his freedom to give information to the press about working conditions. The only thing that really saved him was that the society there was so racist that they couldn’t imagine that a construction worker like him would even be capable of speaking to a reporter on equal terms.

Guernica: In terms of influences on your art, you note that you read David Sweetman’s Explosive Acts: Toulouse-Lautrec, Oscar Wilde, Félix Fénéon, and the Art & Anarchy of the Fin de Siecle at age fourteen, and that it taught you that “art and action could infuse each other.”

Molly Crabapple: The book was not really the most historically accurate, but sometimes a false history can really inspire you. It was the idea that you could do this art that was superficially about something very beautiful, sexy, and decadent, but the sex and the decadence could be weapons. They could be intensely subversive things. Like in the art of Toulouse-Lautrec, someone could be both a cancan girl and a scathing critic of all that was wrong in the world. I liked the sense of defiance hidden behind the ruffles.

Guernica: That reminds me of when you wrote about your time as a model and sex worker with burlesque performer Amber Ray, who taught you that glamor could be a weapon.

Molly Crabapple: Different types of sex work are differently supportive. If I were working in a strip club, I would be competing with my colleagues, and while there would be support, there would be financial motivation not to offer too much support. But with the work I did, we had to rely on each other’s referrals, so by necessity, we were very supportive of each other. We weren’t necessarily super sweet about how we all looked, but we wanted to keep each other safe. I made some of my best friendships in that world, too. At a certain point years ago, I had difficulty being friends with women who hadn’t worked in either the sex or beauty industries. I felt like other women sometimes overvalued beauty and sexuality, when in actuality, they’re just parts of a job.

My friend Melissa Gira Grant had this amazing line. She said that perhaps the greatest and most subversive truth that sex workers possessed was the realization that a dick was just a body part, like an elbow. It isn’t something that could destroy your soul, it isn’t something that you should bow down to. It’s just a body part.

Guernica: In the past, you’ve used Kickstarter to fund projects like Week in Hell, in which you locked yourself in a room for five days and created large-scale drawings. Do you see crowdfunding as an alternative patron system?

Molly Crabapple: It absolutely is. I feel like the traditional patron system meant that you would kiss the ass of one rich person and then hide all of the financial goings-on of your work, and you could pretend you were pure. But you still have to kiss one person’s ass, and I didn’t want to be beholden to one person. So I did something where I had hundreds of people who backed the work. I could just do work, and since a lot of people were interested in it, I wasn’t beholden to any particular one of them, right?

The thing is, while I loved the people who were really interested in my work, there was a certain level of accessibility and interchange that people wanted. Because I was doing so much work, I found that I couldn’t do the labor of my actual work and still be accessible to supporters. In general, I get a lot of emails from people who are in really hard positions. For instance, I might get an email from a queer teenage refugee, who is living in a country with very homophobic laws. Him I would respond to, but I can’t respond to everyone.

Guernica: In an essay for Vice in 2013, you wrote about your abortion. It seems that the stakes have gotten much higher for how people talk publicly about abortion. Do you think you could tell that story in the same way today?

Molly Crabapple: I would. The truth is, the vast majority of medical care for lower income people in America is shitty. If you go to a free clinic to receive any form of care, the majority of those will be overcrowded with nurses who are tired because they have to work with so many people. We are not a country that invests public money into taking care of poor people, so we usually rely on clinics with very overburdened and underpaid staff. In the case of Planned Parenthood, it is a terrorist target, and because of this, security measures are required, which end up making everything shittier. I don’t blame Planned Parenthood for that; I blame terrorists that go in and shoot their doctors for that. What made my experience bad at the Greenwich Village Planned Parenthood twelve years ago was that these were extremely overworked, stressed people who were, and are, under terrorist threat.

I also had a lot of shame about abortion that wasn’t religious shame, it was almost like this sort of classism. I had absorbed this weird message that an abortion was done either if you were raped or you were ignorant and you didn’t know how babies were made or didn’t understand birth control. I absorbed the lie that any smart woman would use birth control and be responsible for her body. Obviously that’s not true. Women have abortions in America for every possible reason. But at the time, I really was angry at myself because I knew how birth control worked. I wasn’t raped. But sometimes, birth control just doesn’t work.

At the time, there was this very illusory sense that by protesting, Wisconsin was joining with Egypt, Tunisia, Greece, and Spain, and it seemed like the whole world was together. Now we’re seeing in so many countries the brutal hangover of that, to put it mildly.

Guernica: You’re also known for your work with Occupy Wall Street. Can you tell me about that?

Molly Crabapple: I started doing that in March 2012. It was after Occupy had been kicked out of Zuccotti Park, which is down the street from where I live. I had this memorialist tendency, I guess, and those days were so fucking vivid. At the time, there was this very illusory sense that by protesting, Wisconsin was joining with Egypt, Tunisia, Greece, and Spain, and it seemed like the whole world was together. Now we’re seeing in so many countries the brutal hangover of that, to put it mildly. But at that time, it felt like something impossible was happening: we were together and it was magic.

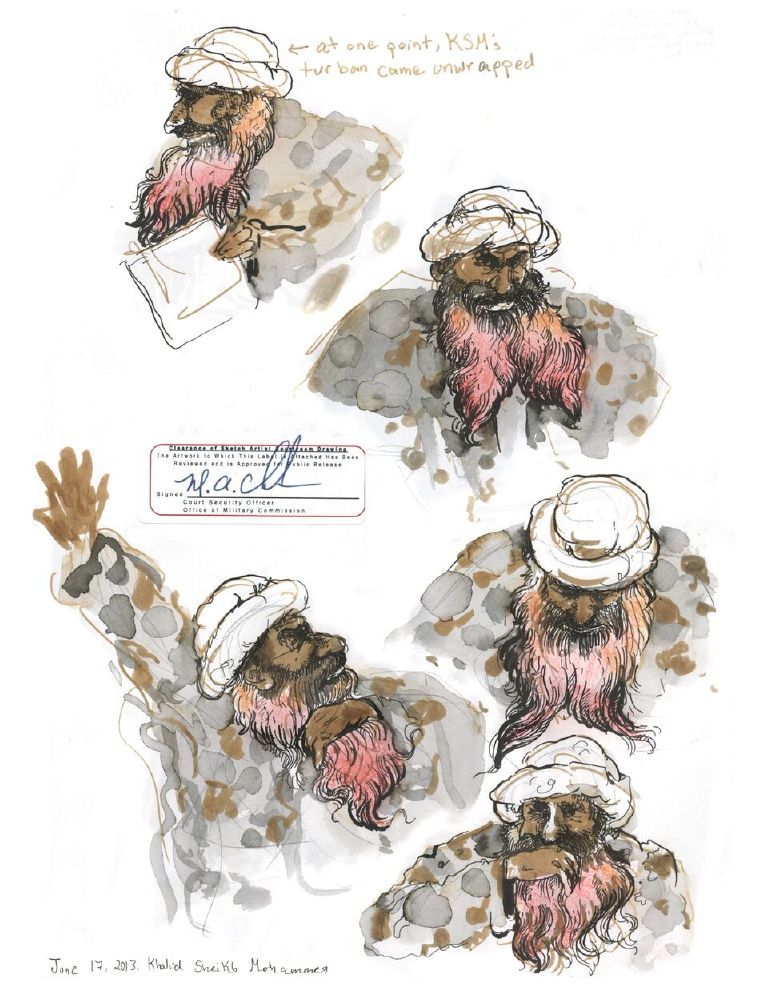

Guernica: After Occupy, you went to Guantánamo Bay as a reporter for Vice. You arrived while the hearings for the alleged 9/11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed were taking place, and you attended a press conference where the relatives of 9/11 victims were speaking about their losses. What was that like?

Molly Crabapple: [At that press conference] in Guantánamo, people were talking about their family members being murdered in the most explicit possible terms. One guy was talking about identifying his father based on the serial number in his titanium hip. I saw that pain, and that pain was very fucking real, and no one should ever demean that pain. But I saw their pain being used by others and turned into a commodity that’s used to justify all sorts of terrible things. I was sitting there, and my heart was being torn up because I remembered September 11th vividly. I’m a New Yorker; they were talking about this thing that I remembered so well, and that they suffered so much more from, and then I was also thinking about Nabil [Hadjarab], the guy that I was profiling in Guantánamo Bay, who was being shackled to a chair and getting a tube shoved into his stomach twice a day for no reason.

Guernica: You wrote about the Guantánamo Bay gift shop, which I’m still trying to wrap my head around.

Molly Crabapple: The thing is, Guantánamo is also a naval base, and they’re under the delusion—especially the people on the naval side who are not dealing with the prison—that they can just pretend this is an ordinary Caribbean naval base. For them, it’s: “Why are you making such a big deal out of the most notorious prison in the world?” It’s like if people living near Buchenwald said they wanted to talk about the other lovely things in the region besides the camp.

Guernica: It’s that disconnect and those small details that really creates the tension in your piece.

Molly Crabapple: The devil is really in the details. Something I’ll always remember in Guantánamo is a chart I saw while I was waiting for the guards to search my things before entering the prison. It was a chart where guards could rate their spiritual health according to a color-coded rating of one to five. It said if you were exhibiting particular signs, you’re spiritually unhealthy, and that you should speak to a psychiatrist or a minister. I thought to myself, “You’re a fucking jailer at Gitmo rating your spiritual health on a condescending color-coded sign!”

One thing about Guantánamo, beyond anything else, is the commitment against all odds to allow Americans to view themselves as the good guy, no matter what the situation is. It’s to the point where there are signs like, “Are you feeling conflicted? Maybe you’re not spiritually healthy and you should talk to someone.” Maybe you shouldn’t be working as a jailer in Guantánamo. Maybe that’s why you feel spiritually unhealthy.