In a storefront on the east side of Tijuana, US Army veteran Hector Barajas spoke to his nine-year-old daughter in Los Angeles a week before Christmas 2014. He wore shorts and a white tank top. Tattoos arced across his back. His shaved head reflected the glow of the ceiling light. A thin mustache drew a dark line beneath his nose. He lay on a cot in the front office of the Deported Veterans Support House, a nonprofit that stands next to an auto mechanic shop and a karaoke bar and assists veterans removed from the United States. Pizza joints and convenience stores lined the main drag, less than half a block away. At night, dogs roamed the streets, toppling garbage cans. An American flag concealed the glass front door.

Through Skype video hookup, Barajas saw the Christmas tree his daughter had decorated. He told her he wished he could be with her.

“It’s beautiful,” he said of the tree.

Then the video connection shut off.

“I can’t see you,” she said. “Daddy, I can’t see you.”

He tapped his phone. She called out to him but he would not see her again unless he reconnected with Skype or she came down to Tijuana for a visit. Like the men he helps, Barajas, thirty-eight, is a deported veteran. He served in the Army from 1995 to 2001 and received an honorable discharge. He says he was removed from the United States in 2004 for discharging a firearm into a car in Compton, a gang-infested city in South Los Angeles County where he spent much of his childhood after his parents moved there from Mexico. He denied the shooting. He says he served a three-year prison sentence before he was deported. He would have been allowed to return to the States in 2024 but he didn’t want to wait that long. He crossed back into California the same year he was removed to reunite with his family, got caught, and was deported again in 2009, this time for life.

I learned about Barajas and the support house when I began following the immigration case of a Pennsylvania Army veteran, Neuris Feliz, fighting deportation. An Iraq War veteran, Feliz left the Dominican Republic for Puerto Rico and then the United States mainland as a boy. He enlisted after 9/11. He thought it his duty. He considers himself an American. His paperwork, however, says otherwise: he is a permanent legal resident, not a US citizen.

Feliz is also a convicted felon, the victim of his own ruinous choices and that of lawmakers intent on showing their tough-on-illegal-immigration political bona fides through a harsh, inflexible law passed almost twenty years ago. The 1996 Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act, signed by President Bill Clinton, greatly expanded the classification of crimes that allow for the removal of immigrants, including veterans. To the surprise of the deported veterans I spoke to, their military service had not granted them citizenship. Immigrant veterans can be deported for a period of years or for life depending on the severity of their crime.

Today, in addition to such serious crimes as murder and rape, a great many other offenses, when they result in a sentence of a year or more in prison, can meet the definition of an “aggravated felony” and lead to deportation. The US Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency, better known as ICE, does have discretion over whom it refers for removal. ICE, spokeswoman Gillian Christensen told me in an email, is “very deliberate in its review of cases involving veterans.” But the 1996 act does not permit any discretion on the part of immigration judges, who may not take into account a defendant’s military service or any other mitigating circumstances once they have been convicted of an aggravated felony. The act can be invoked against an individual at any time, even years after they have been released from prison. Complicating matters further, non-citizens do not have the right to a government-appointed lawyer. They may hire their own if they can afford to.

Margaret Stock, a retired lieutenant colonel in the Army Reserve, is now an immigration attorney with Cascadia Cross Border Law in Anchorage, Alaska. She told me that before 1996, deportations of military veterans were extremely rare. Now, nearly every day, she said, she consults with a lawyer handling a deportation case or speaks to a veteran facing deportation. The day before I reached her recently, she had consulted on five such cases.

“I do not personally know of any honorably discharged military veteran who was deported prior to the 1996 changes to the immigration laws,” said Stock, a 2013 recipient of the MacArthur Foundation genius grant.

“The pressure is on agents to find criminal aliens and deport them. They get credit for deporting veterans.”

In June 2011, then–ICE director John Morton wrote a memo suggesting a different set of standards for veterans facing deportation. Morton advised that “when weighing whether an exercise of prosecutorial discretion may be warranted,” ICE officers, agents, and attorneys should consider among other factors “whether the person, or the person’s immediate relative, has served in the US military, reserves, or national guard, with particular consideration given to those who served in combat.” But lawyers for veterans facing deportation question how often this happens or whether it happens at all. An ICE spokesperson said that the agency does not specifically track statistics on how many people removed from the United States have prior military service.

“ICE is driven by statistics to show the public they are deporting criminal aliens,” Stock said. “The pressure is on agents to find criminal aliens and deport them. They don’t care if the criminal case is more than ten years old. Immigration agents don’t get a medal for letting a criminal alien go for being a vet. They get credit for deporting veterans.”

In Tijuana, Barajas said he assists about fifty deported veterans and is in touch with more than 200 others in twenty-six countries, including Canada, Jamaica, Trinidad, and the Dominican Republic. These veterans face a host of challenges. Some of them don’t speak the language of the country they were deported to because they left it when they were toddlers. Jobs are scarce and pay little. Those who received an honorable discharge are eligible for Veterans Affairs services through the agency’s Foreign Medical Program, which covers certain healthcare costs related to military service, said VA spokesman Randy Noller. Still, according to attorneys representing deported veterans, mental health services for post-traumatic stress disorder and other psychological problems are few or nonexistent in most countries. Unfamiliarity with their new country makes deported veterans vulnerable to criminals and corrupt officials.

“Over here, it’s the twilight zone,” Barajas told me when I arrived in Tijuana. “You see people walking back and forth across the border and you can’t.”

Deported veterans include those who joined the military and those who were drafted. Many of them, like the “Dreamers,” came to America as children, brought by relatives and with no say in the matter. Had they kept their noses completely clean, or committed a different class of crime, they would have been eligible to pursue citizenship, just like any other green card holder. In some states, they would even have been allowed to pay in-state college tuition, just as though they belonged.

But they don’t. Last year, ICE removed 315,943 immigrants. Among them, 56 percent or 177,960 had been convicted of crimes as serious as drug trafficking, or as minor as entering the country illegally. The data do not quantify how many of the deportees were veterans.

About 25,000 non-citizens are today serving in the US military, according to a Department of Defense spokesman, or a little less than 2 percent of active duty forces, and approximately 5,000 non-citizens typically enlist each year. In a 2005 study, “Non-Citizens in Today’s Military,” the Center for Naval Analyses found that “non-citizen servicemembers offer several benefits to the military,” most notably, racial, ethnic, linguistic, and cultural diversity. “This diversity is particularly valuable as the United States faces the challenges of the Global War on Terrorism.” It also found that non-citizens have substantially lower attrition rates than white citizens—9 to 20 percentage points lower over thirty-six months.

In March of this year, the US Army enlarged a new program that encourages legal immigrants with “in-demand skills” such as Arabic and other languages to join the armed forces “in exchange for expedited US citizenship.” The Military Accessions Vital to the National Interest program, known as MAVNI, will seek 5,000 enlistments next year, almost double its current level.

“Because the MAVNI program has been extremely successful in filling our ranks with highly qualified soldiers who fill critical shortages, we expanded the program,” said Army spokesman Hank Minitrez.

But any recruits who haven’t yet become citizens—or who aren’t already in the citizenship process—run the risk of deportation should they run afoul of the law. After serving prison sentences, they are punished further and far beyond what an American citizen would experience for identical offenses. They are being kicked out. Their military service does not entitle them to a second chance.

“You don’t have to like them,” said immigration attorney Craig Shagin, who represents veterans facing deportation. “They served in our uniform and under our flag. They took an oath to defend the Constitution. If they get shot, no one says, ‘They’re Mexicans.’ They are ours. Why when the uniform comes off are they shifted back to lawful permanent alien? When is it they are not ours and why?”

The veterans I spent time with weren’t angels. They had been convicted of serious and, in some cases, reprehensible offenses. But no matter what they did, they served and in some cases fought and risked their lives for the United States, just like citizens.

Stock said she is unaware of a single case in which a deported veteran successfully appealed removal and returned to the United States. Veterans have only one sure way to reenter the States legally. When they die, those not discharged dishonorably are eligible for a full military funeral in the United States.

Unwanted alive, they can return home as a corpse.

In late January 2015, I sat with Neuris Feliz in the dining room of his Lancaster, Pennsylvania, apartment. A late January morning, shades drawn, the gray light of an overcast winter morning barely breaking through. The horse-head profile embossed against the yellow shield of the 1st Cavalry Division with which he served in Iraq stood on a desk. Near it, a photo of Feliz in his Army uniform, an American flag behind him.

Three deflating heart-shaped balloons from his thirty-first birthday party the night before sagged above our heads. A poster on the wall behind them read, Live, Laugh, Love. Feliz looked younger than thirty-one. Black hair, wide brown eyes, a weary smile. Just he and his wife and a bottle of pink wine, a red ribbon slipping down it. Happy birthday. Perhaps the last birthday he would celebrate in the United States.

“I live here,” he told me. “Hell, my favorite sport is football.”

But he was not from here. Feliz was born and raised in the capital of the Dominican Republic, Santo Domingo, with a brother and three cousins. Early in his childhood, his mother, separated from his father, left him with an aunt and moved to Spain and later Puerto Rico to find work.

He spent much of his time in the countryside of the Dominican. So free. Not congested like Santo Domingo. He remembers canyons deep and wide, small wood houses, and all types of fruit. There were sheep, cows, horses, sugar cane, too, and coffee plantations. Clouds concealed the tops of mountains and fog descended across valleys at night with the stealth of ghosts. In the morning, he wore a jacket until it warmed.

In 1995, when he was eleven, Feliz traveled to Puerto Rico to rejoin his mother, who had returned there from Spain. Four years later, they moved to Lancaster, where other family members lived. The weighted mugginess of Pennsylvania’s humid summers surprised Feliz. The nineteenth-century brick buildings with their sagging wood porches looked ancient. He had never seen so many white people up close.

He thought of the United States as his country. No one had told him otherwise.

He attended summer school, enrolled in English as a Second Language classes. Within a year he’d learned the language well enough to participate in classes with American students. His aunt taught him multiplication, slapping his knees with a belt when he answered incorrectly. He fell in love with science. He wanted to be an astronaut.

He grew restless as he advanced into his teens, however, and school no longer captured his imagination. He spent his high school senior year clubbing and drinking. He didn’t bother to attend graduation. If he could talk to the young man he was then, Feliz would tell him, If you lose your love for school, you lose everything.

The terrorist attacks of 9/11 refocused him. He thought of the United States as his country. No one had told him otherwise. In 2002, he signed up with the Army National Guard. Within a few months he went active.

“With me, it was, ‘You want to join? Sign here,’” Feliz recalled. “I don’t remember [the recruiters] saying anything about status. But they did ask for my green card.”

One year later in March, while he was walking ten kilometers and carrying a ninety-pound rucksack as part of a three-day war games drill, the United States launched airstrikes against Iraq. Feliz didn’t grasp that a war had started. That was part of being in the Army. Don’t think, do. He loved that. That sense of purpose. Just do. Civilians stopped and watched him when he walked past them in his uniform. How impressed they looked. He didn’t know anything to beat that feeling.

Feliz, a power generator mechanic in the Army’s 1st Cavalry Division, deployed to Iraq in 2004. He landed in Camp Doha in Kuwait. Three weeks later, the division began a three-day drive to Sadr City in northeast Baghdad. So many people on the street. The convoy inching through jammed markets. Move, move! Get out of the way! the Americans shouted. Some soldiers from the 115th Battalion, including Feliz, bivouacked at Camp War Eagle. The camp would see combat with the Mahdi army, an Iraqi paramilitary force opposed to the Americans.

Daily mortar attacks became the norm. Feliz rode in convoys and heard the gunfire, the ting of metal when bullets struck his vehicle.

For six months, he pulled guard duty six hours on, twelve hours off. Sometimes, he directed vehicles entering the camp and driven by Iraqis into a large concrete box to contain a blast should the vehicle be wired for a bomb. If it blew up, so would he.

One hot evening in April 2004, Feliz stood by the camp’s main gate and heard explosions. OK, he thought, another firefight. Then he saw a truck racing toward the gate. More vehicles came behind it, all of them carrying wounded. He heard someone shouting, Medics! Medics! He responded automatically. He and others of his squad put the injured on litters. Ankles, arms, legs all shot up. Everyone running so fast. Seven or eight people died. He realized where he was. Iraq. In a war. Not a war exercise, but a real war. He told his pastor he had blood on his hands from trying to help the wounded. Not long afterward an IED killed a close Army friend, Leslie Denise Jackson.

She had worked in supply and drove back and forth between Camp War Eagle and Camp Muleskinner in eastern Baghdad. Her vehicle struck an IED. Feliz heard the explosion. He had no idea her vehicle had been hit until he got off guard duty. His squad leader told him. He couldn’t believe it, choked back tears. She was only eighteen. He could not get her out of his mind. “I didn’t join the Army for this,” she used to tell him when a mortar hit and wounded had to be treated. Meaning the killing and dying were getting to her. For days after her death, Feliz kept recalling her words: “I didn’t join the Army for this.”

He changed. No more don’t think, do. He talked back to his supervisors. He didn’t complete his work. His superiors, he said, did not suggest he seek counseling, though an Army spokesman said counseling would have been available to him at the camp. Instead, they allowed him a four-day leave in Qatar. From there, he spoke to his family and pastor.

“He was depressed, crying,” recalled Cesar Melo, pastor of the Iglesia Poder de Dios en Acción, or Church of God Power in Action, in Lancaster. “He saw parts of the body of his friend after the explosion. He didn’t understand why we had to go to war. He didn’t want to live. He wanted to go home.”

When he returned to Camp War Eagle, he assumed his old don’t-think-do attitude. He told everyone he was OK. To all appearances he was.

In 2005, Feliz reenlisted just before the 1st Cavalry received orders to return to the States. Once in Fort Hood, Texas, everyone took a thirty-day leave. Feliz returned to Lancaster. He stayed drunk the whole time.

Back at Fort Hood and awaiting redeployment to Iraq, Feliz continued drinking. He did not seek counseling. He did not consider he had a problem. But he couldn’t keep himself out of bars. He had an on-again, off-again girlfriend. When they were on he wouldn’t let her out of his sight. He didn’t want to be alone.

“I was very selfish, very possessive. I was running from my life,” Feliz said, describing that time. “I felt very alone.”

In May 2005, after a day of drinking, Feliz drove to his girlfriend’s apartment at night. A guy stood in the parking lot waiting for her. He said they were dating. When she drove up, Feliz took an ax handle from the trunk of his car and ran up on the guy as he was getting into the car. Feliz began hitting him with the ax handle, swinging like a baseball player, striking the guy four times around his right knee and ankle, the guy screaming and trying to shield himself, the girlfriend screaming, the guy half falling, half jerking himself into the car and slamming the door shut.

Feliz ran to his girlfriend’s side of the car and cussed her out as she sped off. He watched them leave. She had her two-year-old son with her. He remembers that. He doesn’t like that he cussed around him. He was drunk and angry. He left his girlfriend’s place, drove to a strip club, and drank. To this day, he said, he does not know why he had the ax handle or even how it got in his car. For protection, he thinks. But he cannot imagine from what.

That night the police questioned him at his apartment. He told them what happened in the parking lot and gave them the ax handle. The police left without detaining him. A week later, they called and told Feliz to come to the station for more questioning. He didn’t. He didn’t give a damn. Another week passed and the police called again. This time they told him to turn himself in. He complied. He still didn’t give a damn. He just wanted to get whatever might happen over with. He says now he could have asked the Army for legal assistance, as an active duty service member, but instead he went with a court-appointed lawyer. He didn’t care what might happen.

Feliz pleaded guilty to aggravated assault. According to court records, the judge asked him if he appreciated that by pleading guilty the United States could choose to “deny you the right to remain in this country, they might deny you the right to apply for citizenship and they could in fact deport you from this country. You understand that?”

“Yes, your honor,” Feliz said.

The judge sentenced him to five years. He was twenty-two. Feliz says now that he does not recall the judge speaking to him.

“I just remember saying yes to everything,” he told me. “I don’t remember much. I was just going with whatever they gave me.”

A few weeks later, when we spoke by phone, he reflected on his sentence.

“My lawyer wasn’t that much of a—” he began and then paused. “He was court-appointed and didn’t do much. He told me I’d get probation and then the day of sentencing he told me the DA was asking for four years. But really, I didn’t care too much.”

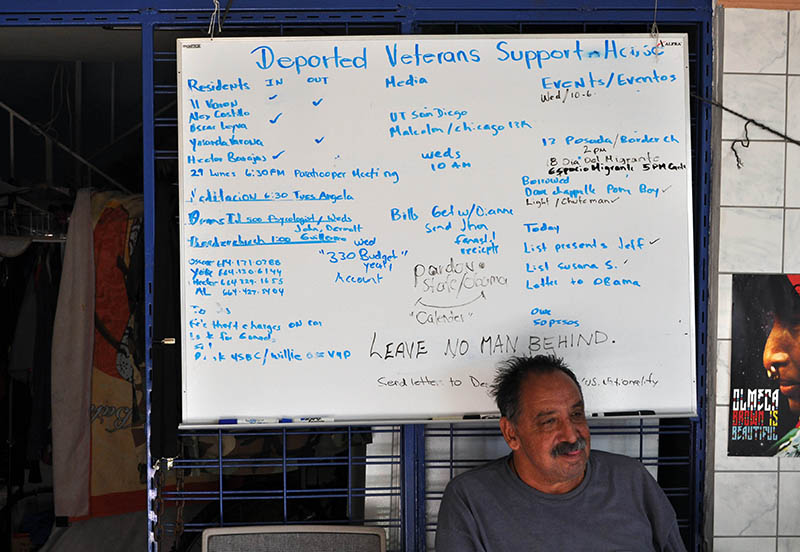

Hector Barajas ironing his dress blues at the TJ support house. He dresses in uniform to protest at the border on behalf of deported vets.

After two days with Barajas at the support house in Tijuana, I took a bus to Rosarito, a town farther south along the coast, to meet deported veteran Alex Murillo.

Murillo, thirty-seven, has thick black hair and an easy manner, liberally dropping the word “dude” into every other sentence. On the afternoon I showed up at his apartment, he was talking on the phone to his eldest son in Phoenix.

“How you doing?” Murillo said to him. “How’s school?…All right…Nothing. I’m watching Planet of the Apes. The latest one.”

Murillo was born in Nogales, the last one in his family to have been born in Mexico. He was an infant when his parents moved to Phoenix. He remembers nothing of his birthplace. He grew up as an American kid. He played baseball and basketball. Didn’t care for soccer. He scored As in grammar school and was on the honor roll in junior high.

“What’s going on in school…What do you mean?…I thought you were getting good grades.”

As a high school sophomore, Murillo started screwing up. Treading that line between dropping out or not. Spending too much time with his girlfriend. He did graduate but his grades had sunk so low he was ineligible for college grants and financial aid. His parents didn’t have the money to send him.

In October 1996, after his girlfriend became pregnant, he joined the Navy. Quit screwing up, he told himself. Make your family proud, take care of the baby, and after your enlistment, attend college. Get into law enforcement. Something exciting.

“How’s it gone down to Cs, son?…Straight Cs? That’s a straight average. How are you going to get into college? What are you having problems with, son? You were getting As and Bs.”

Murillo became a naval mechanic. He said he was voted honor recruit in boot camp and graduated top of his class in aviation school in Pensacola, Florida. He loved the Navy but hated it, too. Loved the camaraderie, meeting other sailors from all over the United States, but had a phobia of being swallowed by the ocean and floating away into nothingness.

After three months at sea, he returned stateside for a brief break before beginning a six-month deployment. He started drinking a lot then. Young marriage and baby all at once, away from his family. Twenty years old, he was just a kid. Maintaining equipment, working sixteen- to eighteen-hour days. The job wore him down.

His ship, the George Washington, returned to Norfolk, Virginia, in 1998. He drank more and more. He got popped on a piss test for marijuana. He was placed on restriction. One night, he cut his wrists with a razor blade. He doesn’t think he wanted to kill himself. Maybe he did. Or maybe he just wanted out. He spent about two weeks in the psych ward. He spoke to a chaplain often and to a doctor a few times. The doctor jotted comments in Murillo’s file. He doesn’t know what he wrote anymore than he understands how the doctor helped him. When he was released, he left the Navy in 1999 with a bad conduct discharge.

“I’m going to stay on you about your homework. Bring back As and Bs. More As than Bs. I have to stay on you…I know, son…I want to see you. How’s your mother doing? I’m trying to get a job.”

Murillo returned to Phoenix and continued drinking. His marriage, already rocky from his time away, worsened. He and his wife tried to make it work and had two more children but the marriage didn’t last and they divorced. His drinking began costing him jobs: Home Depot, Cox Communications, DirecTV, he can’t say how many jobs he lost. He couldn’t pay child support. His wife would not let him see their children.

He stepped forward, his left foot in Mexico while his right foot remained in California until he raised it, too, and crossed over.

In April 2009, he found another job, the wrong job. He agreed to transport around 700 pounds of marijuana for a dealer and got busted in St. Louis. He was sentenced to thirty-seven months in the federal prison in Lompoc, California. While he was there, immigration flagged his name. In December 2011, after he completed his sentence, a prison bus carried him to the San Diego/Tijuana border.

“I care, son, because I’m far away. You have to move forward. I messed up. I’m paying for it. You got to be a success, son. I see nothing but good stuff ahead of you if stay on those grades.”

Murillo can still see himself getting off the prison bus at about 11 p.m. He had $120 hidden in his prison sweats, gray on gray, his only clothes. Guards unshackled his hands and feet and he walked off the bus. Pitch black out, the air heavy. A guard gave him a cup of noodles, shrimp flavored. He got one phone call. He tried to reach his mother but the call didn’t go through. He stepped forward, his left foot in Mexico while his right foot remained in California until he raised it, too, and crossed over.

He stayed with a cousin and then moved to Nogales. He didn’t like it there, felt people held his “Americanness” against him. In September 2012, he resettled in Rosarito.

With the help of his family, Murillo recently started a satellite sales and installation company. He coaches football and freelances as a photographer and videographer. His mother brings his children down for visits when she can. They throw a ball on the beach until they leave. He watches them go, that fear he had of the ocean overcoming him, that feeling of being sucked into nothingness.

“Apply yourself a little more, OK, son?…All right. We’ll web chat later? OK. Tell your brother and sister and I love them very much. I love you, son. Bye.”

He put down his cell phone, slumped in his chair. He stared at the wall. He raised his head to the ceiling and covered his face with his hands. He dug his fingers into his forehead and his face broke beneath his hands into tears.

“I just want to get back home, man.”

His voice catching barely above a whisper.

“I just want to see my kids.”

Deported veteran Hans Irizarry, thirty-eight, picked me up at the Santo Domingo airport in the Dominican Republic late on a Tuesday afternoon at the end of January. He stood slouched to one side waiting for me. He had a roll to his walk that at times blossomed into a strut. A dragon tattoo encircled his left arm. He wore a baseball cap tipped down the left side of his head.

I came to the Dominican to meet the wife, uncle, and cousin of Neuris Feliz. Before I left the States, I got in touch with Irizarry through Facebook. Hector Barajas in Tijuana had given me his name. I wanted to spend time with him to get an idea of what Feliz would face should he too be deported to the Dominican. I also wanted Irizarry’s help with translation when I met Feliz’s family.

I rented a car and from the airport we drove to the house of Luis Milanes Mendez, seventy-right, and Yeimi Mendez, thirty-seven, an uncle and cousin of Neuris Feliz’s. He lived with them as a child after his mother moved to Spain.

They remembered him as a normal, calm boy. Humble. He did what he was told. He played baseball and enjoyed swimming. When he moved to Puerto Rico to be with his mother and later to the United States, Yeimi felt his absence. She had regarded him as a younger brother.

Feliz called Luis and Yeimi when he joined the Army. They were so happy, as proud as any father and sister would feel. For him to be part of the US military, the most powerful military in the world, well, that compared to nothing they had ever known.

From Iraq, Feliz wrote to his mother. She sent the letters to Luis and Yeimi and they forwarded them to other family members. He said he missed them all. He wrote about hungry Iraqis and how they reminded him of the poverty in the Dominican. These thoughts made him think of his family and he grew sad and lonely.

He risked his life for America and now it wants to toss him out?

Feliz spoke very little about Iraq when he returned, Yeimi said, not even about the death of his friend. He had always been quiet but the pronounced silence that hovered around him could be felt even over the phone. It was like he was missing a part of himself.

Luis and Yeimi did not know what to think when they heard Feliz had been charged with assault in Texas. They didn’t understand. They didn’t know him to be violent. They felt even more confused about his situation now. Why, they asked, is he facing deportation for a fight? They don’t know US immigration law, but how can anyone say that’s fair? He risked his life for America and now it wants to toss him out?

If he is deported, of course we will take him in, Luis told me. You have to be careful of everything, he would warn him. You have to know where and what to say, what to do. Everyone carries a gun. Don’t get into a fight. Here, they’ll kill you. Don’t try to be brave. It is dangerous. Step on a person’s foot, sorry, and they kill you. That’s how bad this country is.

When Feliz called recently, Luis and Yeimi told him not to give up. OK, he said. They did not hear from him again for weeks. That silence again. Already, a part of him had been removed.

After the interview, Irizarry and I drove to the home of Feliz’s in-laws to meet his wife, who was visiting her family. We had not gone far when two police officers pulled us over. Irizarry showed them his expired Army identification.

“You’re American? You’re the boss,” one of the officers said.

“No, you’re the boss,” Irizarry said.

“We’re here to protect you,” the officer continued. “Anything you can do to help us, we’ll take.”

“What can I tell you? I’m short of money.”

“Anything you consider good, we’ll take.”

“I need money from you,” Irizarry said.

The officers stepped away. There are two kinds of cops in the Dominican, Irizarry told me as he drove off. Traffic cops during the day, like these guys, but after dark it’s the badasses. At night, he won’t stop for the police. The night cops will tell you to get out of your car and take it. Now, you’re walking. Now you’re a target.

“I’ve had police fuck with me,” he said. “They see the tattoos and earrings. ‘Oh, you’re a deportee. We’re looking for some criminals. You look like one of them. Where’re you from? How long have you been here?’ What has saved me is the military ID.”

It wasn’t always like this. Irizarry was born in Santo Domingo in 1976. Those were different days. Cops didn’t shake you down. No bars on house windows to keep out burglars. He could sit in front of his house and not worry about gangs. Every time it rained, he stood outside and played in the puddles or under a gutter overflowing with water. Now kids don’t do that.

After his mother and father divorced, his mother moved to New York City in 1990, taking with her thirteen-year-old Hans, his older brother, and his younger sister. Some aunts and uncles were already living there.

They moved into an apartment at 125th and Broadway. Irizarry learned English easily. After school, he and his sister walked home and he would cook dinner. His mother and older brother worked for a tailor late into the evening. When he turned sixteen, Irizarry got his residency card. He assumed that made him a citizen although he didn’t really think about it one way or the other.

He attended college and studied computer science. Bored, he dropped out. His mother got on him, What are you going to do with your life? He didn’t know. But he always liked war movies. The more he thought about it, the more he thought the Army would offer him a future. He certainly had no sense of direction now. So, on a whim in 1997, he walked into an Army recruiter’s office and asked, How can I join? The recruiter did not ask about his status. Four weeks later, he was in boot camp.

Irizarry and I stopped outside a tall, multistoried house that stood behind a concrete wall. Feliz’s wife, Carolina Martinez, opened a heavy metal door in the wall to let us in. Yard cats trailed after us into the kitchen and up a flight of stairs. We sat near a balcony enclosed behind bars. A photograph of Carolina’s father in a military uniform hung on a wall. A maid brought us orange juice.

Carolina, twenty-nine, had known Feliz since they were children. Then they lost touch but met again in Pennsylvania when she was visiting her sister. He had been out of prison for six years then. He was not a typical Dominican man. He was not macho. He seemed very open-minded. He did not hang out with other women. He wanted children and to grow old with a wife.

If he gets deported, he will use his military knowledge to survive. But that may not help him. People here pick fights for anything.

After they married, he showed her photographs of dead bodies in Iraq. Very ugly things. He told her Iraq was not easy. He had nightmares. He kept saying he wanted to go back. Before they married, she said, she had not seen that part of his personality that had been affected by war.

Carolina was in Lancaster when custom officials detained Feliz in Puerto Rico. He had called her that morning before he left Santo Domingo for San Juan. She worried when she didn’t hear from him the following day. She wept when he finally called and told her what had happened. She still cries about it. She tells herself everything is going to be OK, but she can’t be certain.

If he gets deported, he will use his military knowledge to survive, she told me. But that may not help him. People here pick fights for anything. He doesn’t know how things are.

The US government should give him a chance, she continued. It should look at all the years he has not been in the Dominican Republic. It should look at his military service. He fought for the United States, after all, not the Dominican Republic.

In 1998, while he was in the Army, Irizarry married. He also was deployed to Kuwait as part of Operation Desert Fox, a four-day US– and United Kingdom–led bombing campaign on Iraqi targets. He unloaded tanks, M-16s, missiles. He spent six months in the desert seventeen miles from the Iraqi border. He carried a gas mask with him everywhere, including the latrine. He almost got himself killed when he drove an armored vehicle into a minefield. He stopped, looked, saw mines all around him, and backed out the way he’d driven in.

He returned to the States in May 1999. That June, while he was stationed at Fort Stewart, Georgia, he notified his sergeant that he was taking his pregnant wife to the hospital for a checkup. His sergeant told him if he wasn’t back on base in fifteen minutes he would take his rank. Irizarry, just back from Iraq, wasn’t taking his shit, and went AWOL. He and his wife left for New York. Two months later, Irizarry turned himself in to the Army. In 2000, he received an administrative discharge, which he appealed. It was later upgraded to general discharge under honorable conditions.

While the upgrade resolved one problem, a more immediate issue, employment, remained. He didn’t like people telling him what to do. He didn’t think like them. He behaved as he had in the Army. Tell him to do something, he did it. Just like that, done. What’s next? His coworkers would mess with him. Why are you working so fast? Who you trying to impress? Or, I didn’t tell you to do that, Izarray.

“You did, too.”

“Watch how you talk to me, Izarray.”

“Fuck you,” and he was gone.

Irizarry and his wife divorced in 2003. By then he had two daughters to support. In and out of work, he wasn’t making any money. The bills piled up. In 2004, he ran into an old high school buddy, a drug dealer. If you need money, all you got to do is pick up a package and you’ll make $800, he told Irizarry. Irizarry didn’t ask what would be in the package. When he picked it up, the police were waiting for him. The package held two ounces of heroin. Irizarry was arrested but got out on bail. However, he would face a judge, he said, who had a reputation of sentencing everyone who appeared before him to fifteen years to life. Irizarry jumped bail and fled to Florida, where his father had immigrated. About a year later, the police caught him. He was extradited to New York and sentenced to four and a half to nine years. He served three and a half because of time served in Florida waiting to be extradited.

“If I hadn’t been caught would I still be a hero?”

“Do you think a good father would have done what you did?” I asked Irizarry as we drove back to his apartment. “I mean, transport dope?”

He stopped the car. He turned and faced me. Speaking in a measured tone, a tight grip on his anger.

“Listen, you cannot tell me what is a good father. You do anything for your kids not to starve. I did everything it took. It was an easy way out. It was stupid, selfish. I went to Iraq. I was a hero. I got caught with drugs, now I’m not a hero? If I hadn’t been caught would I still be a hero? A lot of people have done stupid things and have not been caught. They’re lucky. It was a mistake, a stupid, dumb, desperate mistake. You don’t know what people go through.”

In 2007, while he was still serving his sentence, Irizarry received a summons to appear before an immigration judge. According to trial transcripts, the judge said he could not give Irizarry a break.

“I do appreciate your service to the country. I mean that quite sincerely…. But because of the drug convictions, the way the Immigration laws are written, I’m not—I have no discretion. I’m not allowed to consider things such as how long you’ve lived here. Your family ties to this country. Whether you’ve served in the military. All those things that show that you would be a desirable member of society. Because of the seriousness of the conviction, I have no discretion. I’m a delegate of the Attorney General. I have to follow the laws as written and the law—the way the Congress has written it says I can’t even examine those things. You’re not eligible to apply for any of the applications that would allow me to consider those things.”

The judge then issued the following order: “It is HEREBY ORDERED that the respondent be removed from the United States.”

On October 13, 2008, after he had exhausted his appeals, immigration authorities escorted Irizarry to a plane bound for the Dominican. When he landed in Santo Domingo, police took him and other newly deported men and women to a police station for registration. A man took their photographs. Another man registered their fingerprints. They stood in different lines identified by the crimes that led to their deportation: drug felons here, possession of a firearm there, and so on. The intake took about two hours. The police taunted him. You’re going down, motherfucker. Oh, we got another for drugs. We got you, motherfucker. Irizarry paid a cop $2,000 to delete his registration so when he looked for work no potential employer would know he had been deported.

He found a job in Santiago, about an hour outside the capital, helping a man rent houses. When the work dried up, he returned to Santo Domingo. He works at call centers now, similar to telemarketing, and earns about $180 a month.

“Sometimes I think of going to Mexico and crossing over into the US,” Irizarry said. “If I could see my daughters. If I could see my father. He has Lou Gehrig’s disease. I can’t see him. Believe it or not, some people learn from their mistakes. I’ve learned. I would give what I don’t have right now to see my family.”

Irizarry and I left the house of Carolina Martinez and drove to his small apartment: bright yellow walls, tile floor, two bar stools the only furniture. He had a Chihuahua, “Tony.” The name reminded Irizarry of New York. Once we were inside, he double-locked the front door. Then we called Feliz’s mother, Juana Feliz, sixty-one, in Puerto Rico.

She recalled how scared she felt when Neuris deployed to Iraq. Many times he didn’t call. She didn’t know from day to day if he was alive or dead. She did not earn much so when he told her he had enlisted in the Army she thought, “Wow. He can have a bright future. The army can do much more than I can do for him.” She assumed the Army would enroll him in school. Instead, it sent him to war.

When he came home in 2005, he locked himself away. She didn’t know know what had happened over there. Something. Days, weeks he didn’t talk to her.

She did not hear about the fight over his Texas girlfriend until two months after it happened. You know how men are with their mothers, she said. Only when he was locked up did he tell her.

She did not understand why the United States wanted to deport her son. She was suffering through what only a mother would understand and taking all kinds of medications for her nerves. Neuris broke the law but she asked for forgiveness as a mother for her son.

“Please keep in mind it is not the end of the world,” Irizarry told her. “There are more people here like your son. You’re not alone.”

“You’re in the Dominican Republic?”

“Yes. I’m a veteran. I was deported.”

“Oh, my God, they did that to you, too?”

“Yes.”

“I’m going to cry.”

“Don’t cry.”

“I’ll pray for you.”

“Don’t feel sorry for me. At least I’m not dead in Iraq. Neither is Neuris. You still have your son.”

I left the Dominican the next day and stopped in Miami to visit Guillermo Irizarry, sixty-five, Hans Irizarry’s father, at Franco Nursing and Rehabilitation Center. I wanted to ask him about his son but his illness had progressed to the point where he could no longer talk or move. He breathed through a tube in his neck, was fed through another tube in his stomach. The machines keeping him alive made clicking noises. He lay on a bed, hands at his sides, palms down, and stared at me. I didn’t want to leave without saying anything. I approached his bed and introduced myself. I told him I had seen Hans. He had a job, I said. He had an apartment. He said to say hello. He said he was sorry for messing up.

His father listened, eyes tearing, roaming my face. He opened his mouth, watching me, but made no sound. I wanted to think he heard and understood me. But there was no way to know.

After Feliz told me about the ax handle assault, I spoke to psychiatrist Judith Broder, founder of the Soldiers Project, a national nonprofit based in Los Angeles that provides counseling for post-9/11 servicemen and women. She was not surprised by Feliz’s post-deployment behavior.

A sense of alienation, reliving traumatic experiences, and anger can all contribute to drinking and drug abuse and other self-destructive actions, Broder said of soldiers returning home from war. How much of this behavior has led Iraq War veterans to prison is unknown. Available information is woefully out of date. The most recent veteran incarceration data from the US Department of Justice dates back to 2004, just one year after the Iraq war started. It found that 10 percent of state prisoners reported prior service in the US armed forces. A majority of these veterans served during periods of war but did not experience combat duty.

Few people would dispute that soldiers are often ill-prepared to return to civilian life and that lack of preparation can lead to problems legal or otherwise. A 2008 RAND report, “Invisible Wounds: Mental Health and Cognitive Care Needs of America’s Returning Veterans,” found that 300,000 veterans who had served in Iraq and Afghanistan suffered from PTSD or depression. In addition, about 320,000 may have also suffered traumatic brain injuries.

Symptoms of PTSD include aggressive, hyper-alert behavior that, while necessary for survival in war, creates problems in civilian life, Broder told me.

“Veterans talk about a zero to ten anger reaction,” she said. “Their anger goes off instantaneously and escalates to ten very, very fast. It is a combination of post-traumatic stress and being hyper-reactive to anything that constitutes a threat.”

Such feelings may have led Feliz to put an ax handle in his car.

“Many veterans we see keep weapons at home,” Broder said. “They keep them under the bed, in the car. They even bring them into therapy sessions. They sense danger all around. There’s no on/off switch.”

In 2007, while Feliz spent a second year in jail, the Army hit the switch on his military career. Unable to complete his second enlistment, he received a general discharge under honorable conditions.

With time off for good behavior, Feliz served three years and one month in prison. After his release in 2009, he returned to Lancaster where he took a job at Tyson Chicken. The following year he enrolled in Thaddeus Stevens College of Technology. He started dating the sister of his brother’s wife, too, a Dominican he had known since childhood. In 2011, he returned to the Dominican Republic to meet her family. His life, he felt, was on an upswing.

Feliz spent about two days in Santo Domingo before he flew to San Juan, Puerto Rico, to visit his mother, who had returned there after he joined the Army. As part of their routine procedures, airport customs officers checked his name as they did for all passengers and became aware of his felony conviction. They took his passport and green card and detained him for nine hours before they gave him a summons to report to an immigration judge in Philadelphia.

Since then, Feliz has been fighting to remain in the United States. His Lancaster attorney, Troy Mattes, argued in February of this year before the Immigration Court in Philadelphia that as defined under immigration law, “aggravated felony” differs significantly from how the Texas penal code defines it and therefore does not apply to Feliz. In other words, Feliz’s crime, he said, does not meet the definition of a crime of violence as interpreted by the board of immigration appeals and federal courts.

A ruling is expected later this year. If the judge rules against Feliz, he can appeal.

“This guy served in a time of war,” Mattes said. “That in itself is a circumstance to be considered by the US government. He did this [crime] ten years ago. He did his time. Give him a second chance.”

Feliz has tried to get on with his life. He graduated from college in 2012 and accepted a job with a graphics company. He married in 2013. However, nothing he does feels certain, secure. He does not know his future and where he will live it.

He has no interest in seeking out screening for post-traumatic stress disorder. He wants to do things other than fight.

At night, when Feliz does not dream about prison, he sometimes dreams about Iraq. He is in his barracks when Boom! Boom! Mortars explode. He sees himself on guard duty escorting cars into the concrete box.

He has a packet of photos in a plastic bag. Photos of exploded bodies, traces of blood, brains, burned vehicles. An Army buddy, an infantry soldier, took them and gave them to him. They’re memories, Feliz said. He doesn’t look at them and go crazy. They’re just there. In a desk drawer.

His mind wanders. If he is deported, he knows he can adjust to the Dominican Republic. He has been to war and prison. He can do this, too. He has no interest in seeking out screening for post-traumatic stress disorder. He doesn’t really care. He is unwilling to fight as hard as his lawyer and his wife. He’s almost done fighting. He’s thirty-one. He wants to do things other than fight. He wants it to be done.

In Tijuana, Hector Barajas posted a notice on Facebook: “March 10, 2015. With great sadness. Our brother Gonzalo Chaidez, 64 years old deported US Army veteran passed away at 5:30 a.m. at the general hospital in Tijuana.”

Barajas won’t stay in Mexico. He has applied for US citizenship. If he doesn’t get it, he will seek asylum. He’ll do something. He considers his daughter. He won’t die in Mexico.

Some days, Alex Murillo sits in his Rosarito apartment and thinks back to his childhood in Phoenix. One time he overheard his mother talking about a cousin who had been deported. At the time he thought, That sucks, and then went out and played with his friends. He didn’t dwell on it. He certainly never thought it would happen to him. As far as he was concerned, he was an American. Still feels that way. He served in the US Navy. Saluted the flag. Be all you can be. Standing in front of a mirror at boot camp for the first time in his black-on-black night watch uniform. Wow. Look at him. His parents saw him graduate as an honor recruit. He was on his way. God and country. No one can take that feeling from him. His kids won’t get kicked out. They are Americans. No one can take that away from him either.

Hans Irizarry does not want to die in the Dominican Republic but he suspects he might. He saves his money and recently bought a kitchen stove. Beats the hell out of the little electrical hotplate he had.

He still gets depressed. A few times he has called a suicide hotline in the States. Once he explained he had been deported. The voice on the other end said he could do nothing for him. Sorry. If you feel like talking again, call us.

Irizarry misses cold weather. The first day of snow. It looks so beautiful. All the snow in the trees. Here in the Dominican, he feels trapped inside someone else’s body. His mind is elsewhere but his body is here. He can describe what he’s thinking but the people here don’t understand. They’ve not seen it. They can’t envision it. He thinks, Fuck, I’m not home, and then everything inside him dies.

He doesn’t belong here.

This article was reported in partnership with The Investigative Fund at The Nation Institute, with support from the Puffin Foundation.