I. The Matinee

From outside the Southland Greyhound Park could be mistaken for an enormous bowling alley—all angles and red neon stripes that light up first to mirror, then exceed, the setting sun. There was a valet under a jaunty high-cocked awning, which I soon realized was less for high rollers than the elderly. (On the bathroom wall: a red semi-transparent box with a biohazard sticker, full of diabetes testing strips.) Through the plate glass door was a sprawling casino, mostly slots, and past that a crowd in line for the buffet. To one side hummed Sammy Hagar’s Red Rocker Bar & Grill, wreathed in flat screens and giant cutouts of the man himself. It took some wandering to find the escalator that led up to the stands.

Greyhound racing first gained a serious following in the United States in the 1930s, and really took off after World War Two. The Southland track opened at the tail end of that wave, in 1956, in West Memphis, Arkansas, just across the Mississippi River from the city proper. Short on activities after being trapped in Memphis when a distant blizzard prevented my getting home, I found it behind a clutch of chain hotels where I-40 and I-55 briefly converge. The Saturday Matinee, one hundred and fifty dogs in eighteen races, wouldn’t start for another hour.

At the top of the escalator, beyond a “Greyhound Wall of Champions” and some barren poker tables, was a thicket of empty red chairs that stretched down to the wall of windows above the track. A wall bisected this viewing area, and on the far side of it was a bar that I found myself angling toward. On that side of the wall were tables, each with a TV. A few were occupied by groups of men in threes or fours: smoking; jotting on legal pads; watching, on their respective screens, horse races piped in from someplace else.

I picked up an official program and a brochure entitled “How to Bet the Dogs 101,” found a seat facing the track on the back side of the bar’s black granite circuit, and began drinking the first in a series of Bud Lights while studying the program’s smear of digits. Racing greyhounds, like their equine counterparts, get whimsical names: A Nun with a Gun, Mega Werewolf, Yakiteyak, Natural High, Flying Prozac. I gathered, perusing the lists, that each owner or breeder or kennel has its own proprietary naming conventions. Along with Flying Prozac, racing that day were Flying Tank Man, Flying Red Giant, Flying Tigerbaby, Flying Felicity, Flyin [sic] Red Raider, Flying Shu, and Flyin [sic] Brick Road. All were from Lester Raines Kennel, a West Virginia-based powerhouse.

Ultimately I did what I suspect all amateurs do: bet on the dogs whose names I liked most. This generated its own brand of excitement. Not the best policy for profit, it still allowed me, when PJ Santana Moss broke too early and finished third, to throw the slick white receipt for my five-dollar wager down on the table in disgust, an act I very much enjoyed. I bet forty dollars total this way, and to my system’s credit made twenty-six of it back.

While I sat there, drinking and gambling and performing my occasional dismay, a man down the bar was passing in and out of fits of shouting. He was watching the horse races on a screen. “Stay up, one!” he would yell, “Stick it! Stick it!” At one point, he whipped off his hat. “Stay on him, one! Stay on him! Goddamnit!” He’d gotten there ahead of me, and he was still there when I left. In fact, by the time I departed several hours later, none of the old men sitting around when I arrived had moved except to freshen a drink or place a bet. They didn’t sit up front close to the glass, and they didn’t crane to see the track. They sat and talked and smoked and yelled, but while I watched the dogs they mostly watched TV.

The people there get their kicks not from the race itself but the money they’ve bet on it. You cheer not for a dog but your dog; your pari-mutuel ticket is the spring from which your passion flows. It’s certainly not coming from anywhere else. The chairs are too hard to settle into but too soft to be bothered by; the music is platonic, innocuous, songs you’ve heard so many times they’ve largely ceased to register (“Party Like It’s 1999,” “Don’t Stop Believin’,” etc.); the olfactory monotone of cigarette smoke is broken only by an occasional whiff of urinal cake hitching on a draft. Your thoughts have nowhere to land but on the money-pulsing wires beneath your feet. I wanted to get closer, find some other, less expensive outlet for my attentions. I paid my tab, went downstairs, and followed a long fluorescent hallway through a pair of glass doors and out into the afternoon.

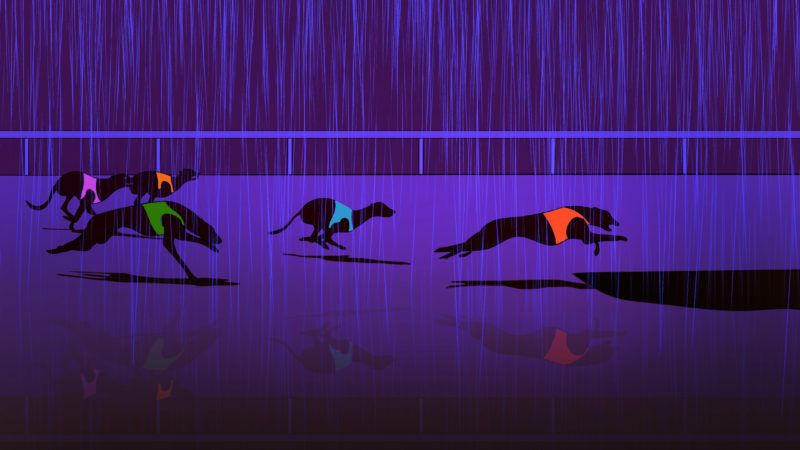

Outside, right up by the track and away from the machines that take your bet, the greyhounds are a blur of legs and numbers that bypass your visual cortex for other, more savage receptors.

Down there, I could easily see how the whole thing had started. There is a lot of listless adrenaline in our lives, resting like dew on grass, waiting to be kicked up by these lean, sprinting hounds. The experience is one of life-and-death stuff, pure predatory instinct. I felt some envy for that single-minded longing. But this sense of it, this rough justice, is a fantasy. High-octane but no less bullshit for it. The end game for the dogs isn’t wild canine glee and a hot pulse of blood between their teeth. It’s what is called a “rabbit”—a stick with a gray foam bone named “Rusty” on the end that they, by design, will never catch.

The impulse to anthropomorphize dogs is strong. We interpret animal behavior through the framework of our own minds, so we’re often wrong about it. It’s easy to perceive a greyhound at full speed as we would an Olympic sprinter, competitive, driven, Usain Bolt in fur. But that is a leap predicated on a lot of assumptions: that greyhounds understand what competition is, that they can conceive of winning or losing, that they prefer the former. And that running is something they choose to do, that their natural aptitude for it reflects the pleasure they take in it, that racing is less something they’re made to do than a naturally occurring behavior we’ve conveniently harnessed and commercialized. None of this is true.

The average greyhound will race twice a week. The rest of their time is spent largely in a 3’ x 4’ x 3’ cage, plus or minus a few hours’ playtime and training per day. Alexandra Horowitz, an expert in dog cognition, told me that this is a “really exaggerated situation” for the greyhounds. “Exaggerated in the wrong ways, which is ultimately destructive.” We were in her office on the fourth floor of Milbank Hall, the stately brick and limestone behemoth anchoring the north end of Barnard College, where she teaches psychology and canine cognition.

Tacked up beside her computer was a series of black-and-white photos of dogs playing in a park—a reminder, I assumed, of what led her to the field. For human children, play, especially play centered on pretending, is a window onto rich cognitive territory. “When a child holds a banana and pretends it’s a phone,” she said, “they realize that it can be something that it’s not. That things are not just as they appear. From there you can enter all these other cognitive realms, so I thought maybe if animals are playing, that would be a fertile place to look into some of these abilities.”

If you’re looking to justify greyhound racing, framing it as play seems like the way to do it. The idea is that greyhounds, long bred to chase things, enjoy doing it, that it’s not so different from running after squirrels in the yard. “They have a reflexive reaction,” said Horowitz. Provide them with something to chase, and they’ll chase it—a sub-rational response. But that it’s natural for them to chase doesn’t mean it’s fun. “You can imagine having a fight-or-flight response if somebody charged in here with a gun. It doesn’t mean that it’s enjoyable for us, or that it’s what we’re meant to do. It’s part of how we’re made, but that doesn’t mean we have to poke at it.”

Horowitz uses the word umwelt a lot. It means an animal’s conception of the world around it, the model an animal uses to understand its environment. Umwelt is the invention of German biologist Jakob von Uexküll, the proper pronunciation of whose name I imagine is a kind of shibboleth in cognitive science circles. The imaginative leap from a human umwelt to a dog’s is a big one. It requires throwing out some of the central features of human experience—jealousy, pride, competition. Absent these motivations, the complexion of dog racing changes dramatically.

Do they know that they’re chasing a rabbit that they’ll never catch? “No,” Horowitz told me, without hesitation. “I don’t think they know that they’re racing. I don’t think they have a competitive spirit with each other. The competition is totally between the owners, the bettors. The whole conceit of the race is unknown to them.”

So what, then, are we left with? Horowitz likened it to gavage—a force-feeding practice typically used on geese and ducks, who have corn gruel piped down their throats to fatten their livers for foie gras. “I think the racing is like gavaging a person. Yes, it’s something born in us to eat, but this form of eating is a tortured form of eating. And that form of running is probably a tortured form of running.”

It’s somewhat reassuring that greyhound racing has fallen off considerably from its height. In Southland’s case, those golden years were the 1970s and ’80s. It was the only legal place to gamble for hundreds of miles in any direction, and people came to watch and compete from as far away as Illinois. In 1989, visitors bet $212 million on Southland races. But the ’90s were a decade of gradual decline that seems, in retrospect, portentous: the first trickles of water through a dam about to break. Only $33.5 million was bet in 2005, only $18 million in 2013.

The more I came to understand how difficult the racing life must be for greyhounds, the more I wanted to pin this collapse on a great reckoning with the industry’s dark side. Along the Mississippi, where white-robed bathers go wading even now in search of Christ, there has never been a shortage of moral crusaders. Consider that, one foggy January night in 1952, Memphis’s First Baptist Church hosted a pan-denominational vigil, 9 pm to 5 am, against a referendum to legalize horse racing in West Memphis. The various congregations took turns before the altar—Presbyterians and Episcopalians and Methodists and the Baptists themselves. The Memphis Press-Scimitar noted that while some prayed standing and some prayed sitting, that some wore jeans and some wore fur, “there was a feeling of intense sincerity about each.” The next day the referendum was defeated by 173 votes.

So horse racing in West Memphis stayed banned. But four years later, per the whack-a-mole of human vices, dog racing emerged in its place. Once Southland had opened, there was no walking it back, however committed the crusader.

II. Nobody Else to Blame

Just west of Pensacola, a low, straight-backed bridge ushers US-98 over Perdido Bay and into Alabama. On the Florida side is a rocky little beach where people sometimes pull over and fish. On the other are two signs, one for a pawn shop, one welcoming you to “Alabama the Beautiful.” A couple of minutes’ drive beyond, just south of the town of Lillian, is an eighteen-acre farm once owned by Robert Leroy Rhodes, who lived alone for forty years in what he claimed was an old barracks—not much more than a trailer, really, with a set of elk antlers projecting from the front. Rhodes worked security part time at Pensacola Greyhound Track, just back across the bridge. On his farm he raised pigs and some goats, and boarded a few greyhounds at the behest of a local vet. By the time the police showed up, he was sixty-eight years old.

That racing greyhounds are exploited is obvious enough except to the greyhounds themselves, who are unable to conceptualize the system that governs their lives, much less resist it. This is, in part, what makes the whole thing so galling: the complete inability to fight back. These animals become, as John Berger put it, “living monuments to their own disappearance.” But systems of exploitation, even systems as impenetrably efficient as that of greyhound racing, run both ways. They are manifest not only in the lives of the exploited, but also in those of their exploiters. It’s easy to see how horrible the greyhound racing industry is to the dogs. It’s somewhat more complicated to see what it can do to the people who work with them, the subtle evolutions in self that are required to make it all work. Subtle evolutions that can, in the aggregate, lead to something much more dramatic, and equally horrible.

For decades Rhodes had been executing injured, sick, and retired racing greyhounds via .22 caliber gunshots to the head. Based on aerial photographs and forensic analysis of the mass graves on his property, somewhere between one and three thousand of them were buried there. It was difficult to get an accurate count, as the bodies were mixed up with cows and horses that Rhodes also disposed of for local farmers. The smell hung in the air, so thick you could feel it against your skin.

His rate was ten dollars per. A fraction of what a vet would charge, but the money added up; by the time he was caught, he’d collected on three thousand dogs. In his mugshot Rhodes is almost smirking. Square jaw, couple days’ hazy stubble, weak chin recessed between jowls. His wide-set eyes look left past the camera, one gray brow cocked slightly, as though he thinks what’s happening might be some kind of prank. Not long after the picture was taken, Rhodes fingered four conspirators—dog trainers and kennel operators—then went home to his farm. “I don’t condone cruelty to animals in any way,” he told reporters. He said he’d swear on a stack of bibles that the dogs never suffered.

In late April of 2002, an informant contacted Jim Barnes, an investigator at the Florida Department of Business and Professional Regulation’s Division of Pari-Mutuel Wagering, and told him Rhodes might be taking dogs up to his farm in Lillian to be killed. On May 8, in a conference room at the Pensacola Greyhound Track, Rhodes handed over a signed statement. In it he admitted to taking about fifty dogs from the track to be put down that March and April. All fifty were from a kennel operated by Bo Patterson, a trainer who denied any involvement. After handing over his statement, Rhodes started talking.

He said he’d started working with greyhounds in 1951 in South Dakota, where he’d grown up. Retired dogs were used as target practice then. They were set loose in a field to run and handlers would shoot at them. Often they were only wounded, abandoned in the grass to bleed to death. He said it offended him treating the dogs that way, so he started putting them out of their misery himself. This is how you start a career in killing dogs.

In 1960 Rhodes moved to Lillian, bought his place, and opened a greyhound kennel, making extra money by disposing of old and sick animals from local farms. He hired a bulldozer to dig pits, ten feet wide and thirty long, for the bodies. Rhodes said he did the greyhounds like this: he walked them to the edge of a pit, held their collar, put the barrel of his gun to their foreheads, and shot them through the brain. They’d fall forward into the earth. He said he didn’t keep any records, and didn’t want to know their names. He said he must have killed two or three thousand since he’d come to Lillian. He said it was a necessary service and that he wasn’t planning to stop. “I did this on my own,” he said, “and have nobody else to blame.”

Rhodes started listing trainers for Barnes, people he’d worked with. Bo Patterson, John Wilson “Willie” Smith, Paul Discolo Jr., Ursula O’Donnell. He said Mary Creamer, head of security at the Pensacola track, and Barbara Ferrell, another guard, had left his comings and goings out of the log books as a favor. There were more, certainly. The numbers are much too large to make sense otherwise. But Rhodes clammed up after that.

The next day, May 9, he took Barnes out to his farm. In his report, Barnes described it like this: “Bones littered the ground in all directions. A smoldering fire was burning in the pit and the stench was pervasive. The current pit is nearly full. An area of approximately fifteen by six feet is available for use. A pile of dirt and sand is at one end. The majority of the bones visible in the pit are probably bovine or equine, although numerous bones appearing to be rib, hip, and legs of greyhounds were intermingled. Beyond the current pit are patches of bare ground which Rhodes stated indicate the location of other pits he has used.” Barnes left, and Rhodes told him to come back if he needed anything else. On May 22, Rhodes was arrested and charged with felony animal cruelty.

People had been bringing dogs to Rhodes from all over Florida. Of the co-conspirators he named to Barnes, Discolo was picked up at a track in Ebro, halfway to Tallahassee; Ursula O’Donnell at one in Melbourne, southeast of Orlando; Willie Smith all the way in Marathon, in the Keys. Bo Patterson, whose fifty dogs were Rhodes’s most recent victims, ran when he realized Rhodes had named names, and disappeared for two years. David Whetstone, the district attorney in Alabama who brought the charges, said it “opened up the eyes to how sinister [the greyhound racing industry] was.” The manager of the Pensacola track said it was just a process of weeding out “the bad apples.”

Rhodes didn’t conceive of himself as a criminal. I think he believed what he said, that his work was a necessary service, and that he was doing the dogs a favor by providing a quick, clean death. I think he was just trying to scrape by. I think he went to bed one night and woke up thirty years later with a job he never wanted, caught up in a system it was too late to back out of. I don’t imagine he enjoyed it.

But when the investigators started digging up the greyhound bodies on his farm, they found immediately that Rhodes hadn’t been as quick and clean as he’d said. He’d missed, and he’d missed a lot. Dogs were shot in the snout or in the neck or in the jaw. Of the first four they dug up, only one had a fatal wound. I couldn’t understand this; he didn’t strike me as a sadist. It made more sense when I discovered how he’d died: complications from cirrhosis of the liver.

Rhodes died on June 30, 2003, at Baptist Hospital in Pensacola, a couple of hours before the sun came up. He was sixty-nine years old. The case against the others, Discolo, O’Donnell, Smith, and Patterson, died with him. Nobody so much as went to trial. At least as recently as 2010, O’Donnell was back training greyhounds. She’d denied, during the investigation, ever dealing with Rhodes personally; she said she knew nothing about it. But the investigator, Barnes, came up with a check for $230, Rhodes’s name in shaky capital letters across the middle and O’Donnell’s signature at the bottom. Put another way: a check for twenty-three dogs.

III. Rollin’ on the River

Casinos started springing up in Mississippi in the early 1990s, following gambling’s legalization in several counties there. Even before they’d opened their doors, though, Southland’s management realized what a mortal threat casinos posed. They hired consultants and started lobbying the Army Corps of Engineers on environmental grounds, ironically enough, to deny the permits for the riverfront casinos as violations of the Clean Water Act. That effort failed, and soon gamblers were abandoning Southland for casinos to the south. Daily attendance fell into the hundreds. Half the staff was laid off.

That Southland’s attendance dropped in direct proportion with the growth of the casinos in nearby Mississippi is evidence of an important fact: not all gambling is equal. From the first race at Southland in 1956 until Splash Casino opened in Tunica, Mississippi, in 1992, there was no competition, so this didn’t matter. But the thrill of gambling is basically just a blast of dopamine, and dog racing is a conspicuously inefficient way for a gambler to trigger its release when there are alternatives in the card tables or slot machines. Southland, in short, needed to diversify. In the Bible Belt, though, that was easier said than done.

In the early ’90s, West Memphis and Southland were represented in the Arkansas State House by a man named Ben McGee. As the largest single employer in his district, Southland factored heavily into his doings—so heavily that McGee was indicted in January of 1998 on charges of accepting a $20,000 kickback from the track for sponsoring tax break legislation, passed in 1995, that saved them $5 million. Barry Baldwin, Southland’s general manager, said diplomatically, “I don’t recall any money given to Ben McGee for that purpose.” McGee ended up pleading guilty to tax evasion and extortion charges, which included $2,000 he’d taken from a pair of greyhound owners—one of whom was Darby Henry, president of the Arkansas Greyhound Association. Nobody at Southland was charged.

The incident with McGee came after a 1993 vote to legalize video poker machines had failed. There were several efforts in the ’90s to bring other forms of gambling to Southland, but all were defeated under pressure from conservative Christians. Gambling proponents renewed the effort in the early 2000s, emphasizing the casinos’ economic potential. Much was made of the fact that most of the gamblers would come from Memphis, as I had, siphoning money in from Tennessee.

It was the Mississippi casinos’ turn to get nervous. They spent half a million dollars running anti-gambling ads under the auspices of a shell organization called Arkansans for the 21st Century, but in vain. The bill that passed the legislature in the spring of 2005 legalized “electronic games of skill,” a category that included, through some rhetorical finagling, video poker and slot machines. A local referendum was also required. Southland didn’t take any chances. They spent $800,000 convincing the ten thousand registered voters in West Memphis to approve the measure. It passed with 64 percent.

A year later, Southland opened a gaming floor, which replaced the lower level of seats around the track. They’ve expanded twice more since, to the tune of almost $150 million, adding nearly two thousand “electronic games of skill.” They made the valet station bigger, too.

The new casino at Southland isn’t very interesting to look at. Take out the machines and you’re left with a slightly edgier version of a chain hotel lobby. Same blandly hip corporate color scheme, slightly wavier designs in the carpet. What’s distinctive is the sound, all the euphoric dinging and clanging and cha-chinging. It sounds like electronic music played under water, or waves of small brass birds colliding. It’s the sound of a lot of people playing the slots.

This innocent device is as efficient a pleasure machine as any yet conceived. To play the slots is to stroke your psyche in magical, nonsensical ways, which is what makes them so much more attractive than the dog races. Despite their arbitrary nature, you get to put your hand on the thing, pull the lever, have some illusory control over your fate. Nothing between you and your winnings.

To step into a house of gambling is to become a solipsist. There is a certainty that you will win; a powerful disregard for the flaccid mathematicians who’d object. The corollary to this is that when you lose, as you inevitably will, there’s a sense of awful destiny. Had you bet on red instead of black, this dog and not that one, you would nevertheless have failed. The winning or the losing comes first; the game simply complies. A grand conspiracy. We know no indifference, not when we’re gambling. There is something frightening about certainty on that scale, and the capacity to destroy yourself it affords.

At the counter upstairs, where I got my program, a woman offered me a deal—sign up and, since it was my first time at Southland, get a card with twenty dollars I could use in the casino. I agreed that this was an excellent idea. Downstairs, later, I won a couple of dollars, then won back what I’d lost on the races, and then a little more than that. I got the distinct impression that these free twenty-dollar cards for first-timers were rigged to pay out extra. I wanted, badly, to keep playing. It was only when interrupted by a woman who explained in great detail her tendency to forget the card with her digital cash on it (you don’t put money in the machine, you put money in another machine, which puts it on a card, which you put in the machine—the sting of bringing out the wallet is much minimized this way) that the trance was broken. She walked off in the direction of the buffet, and only when she was out of sight did I notice she’d left her card behind. I assumed, her seeming from her story to have become an expert at its recovery, that she’d be back before long to collect it. I turned and left.

My brief romance with the slot machine—I’d never played one before—was the latest in a long and unfortunate string of realizations I’ve had about my own mind, specifically regarding the new ways it’s constantly developing to defy me. But it’s some consolation that in this case, at least, I’m not alone. The slots are a prominent entry in our bulging encyclopedia of psychological manipulation. The ways they work on us are delightfully simple. For example: when you win, things happen. Lights go off, bells. When you lose, they don’t. It is much easier to remember winning and so we get the sense that we win more often than we actually do. This is one of a dozen cognitive tricks the slot machine works us over with, tricks no less effective for being obvious.

Only for about 8 percent of gamblers does playing evolve past entertainment. These are the compulsives, the addicts. Their interaction with dopamine is functionally equivalent to that of someone using heroin. How many of these were at the bar that afternoon, shouting at the TVs? Statistically speaking, no fewer than two. The inefficiencies of greyhound racing make it somewhat unpopular with this sort, though—it’s more of a gateway drug, or one part of a cocktail of things (hence all the TVs, the dozens of races all piled up together). I wondered, sitting there, if they might have something in common with the dogs; the knee-jerk stuff, biological imperatives. Back at Barnard, I ran the thought past Horowitz, who laughed at me.

“Gambling is a brain-body connection. With the dogs it’s a reflex, sort of below-brain, the less cognitive aspects. It’s a visual stimulation that leads to muscular activity, versus a tickling of the amygdala, feeling pleasurable, the pleasure leading you back to the activity, creating that loop. It’s more fundamental—I think it’s mostly like a sneeze.”

What seems to me the common thread in all of this is the passive exploitation of the vulnerable—both people and dogs. The exploitation is so deeply embedded in the system it becomes almost invisible, nothing too conspicuously nefarious, usually, just standard operating procedure; any old Saturday at the track. Southland frames greyhound racing as something dogs enjoy, and caters to people compelled, on a molecular level, to gamble. Rhodes didn’t get rich killing dogs, he got by. A little extra spending money past what the dog track paid him. Was he malicious? Or just ground down by petty cruelty and made numb? He had his story worked out, the justification for what he’d done, which implies he felt it necessary to have one. We are very good at writing these sorts of stories for ourselves, after all.

But the greyhound tracks, at least, are dying. I knew that before I ever set foot in one. Southland today could more accurately be called a casino with an unusually busy backyard. The floods that devastated the Delta in 2011 wrecked the Mississippi casinos but were good to Southland’s. Wagers almost doubled, and have been rising ever since. They were, in 2013, nearly $170 million. It’s only a matter of time before the gates and the sand and Rusty the mechanical rabbit give way to slots, another buffet, more poker machines.

Nearly every year for the last twenty, people have bet less money on the dogs than the year before. Forty-one tracks have closed since 1991. Only nineteen remain, spread across five states—Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Iowa, and West Virginia. Two years ago, GREY2K USA, a greyhound advocacy group, released the first comprehensive national report on greyhound racing. It was damning. It found, among other things, that 909 racing greyhounds had died from injuries or accidents, that over three thousand had suffered broken legs, and that there were twenty-seven reported cases of cruelty and neglect, including dogs that were starved to death, all since 2008.

That day out by the track, I watched a parade of handlers in blue polo shirts lead the dogs down to the starting box. There was nobody else outside, which gave me the distinct feeling of being somewhere I wasn’t supposed to be, but a minute later the handlers wandered by again without so much as a glance at me. The rabbit, Rusty, started on the far side of the circuit, so it had time to gather speed before it passed the box and the dogs took off.

Every time they start the rabbit up, the announcer comes out with a little quip, like, “Rusty is rollin’ on the river,” or, “Rusty is ridin’ the rail.” I wondered, as he produced yet another variation on that theme, how many of these he had up his sleeve. I imagined him, balding, probably, with two fingers on his forehead and a cigarette smoking between them. I imagined a notebook on a desk in a half-lit room, line after line of scribbles. But then came the dogs, and everything else, in that moment when I was so close I could smell them running, was forgotten.