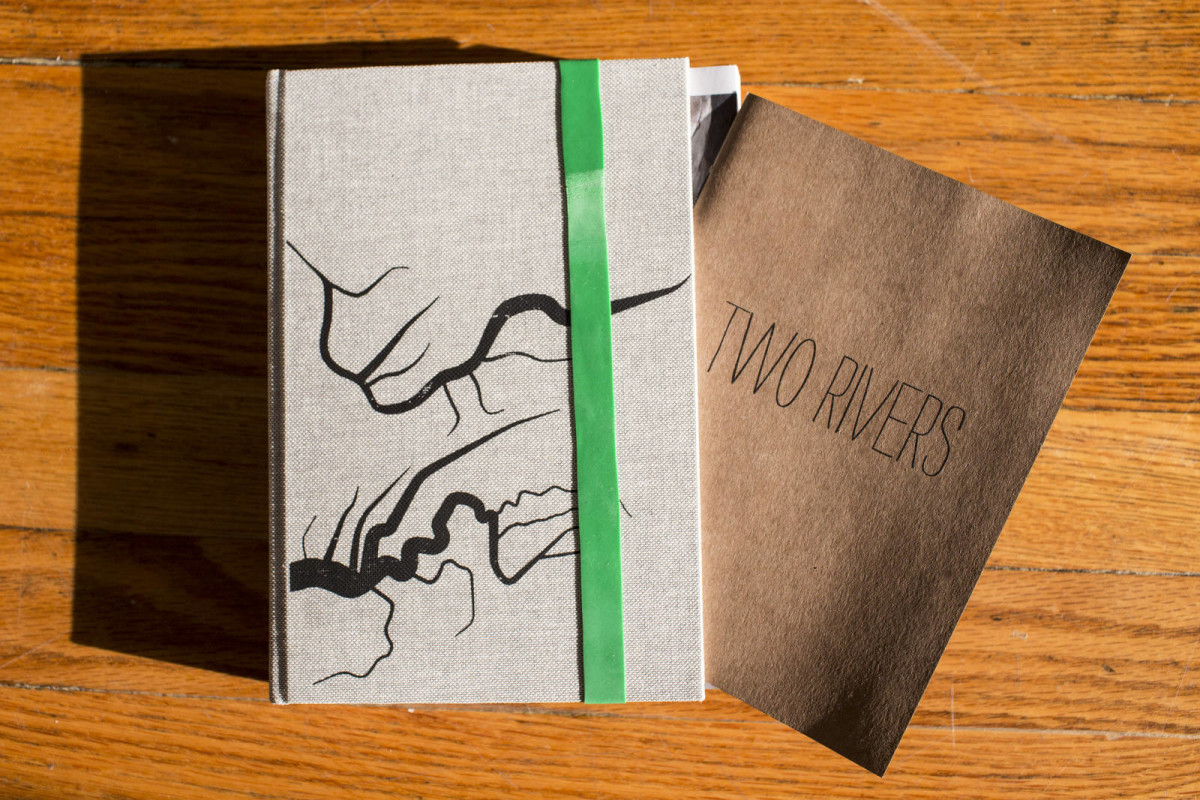

Carolyn Drake’s lyrical photos of Central Asia have been published in National Geographic, The New Yorker and the New York Times. But in putting together her first book, Two Rivers, she didn’t want to simply reproduce her photographs. Instead, along with her collaborators Sybren Kuiper and Elif Batuman, she has created an art object that subverts our idea of what a photo book should be. In this work, the viewer is often denied the pleasure of seeing Drake’s images completely—communicating the frustrations she felt during her working process, and allowing us a rush of delayed gratification when we finally arrive at the magical, full-bleed images of starry nights, elaborate feasts, handmade bridges, and ladies with gold teeth.

The text below is a combination of email correspondence, Skype conversations, and excerpts from Drake’s book. It has been edited and condensed for clarity.

—Glenna Gordon for Guernica

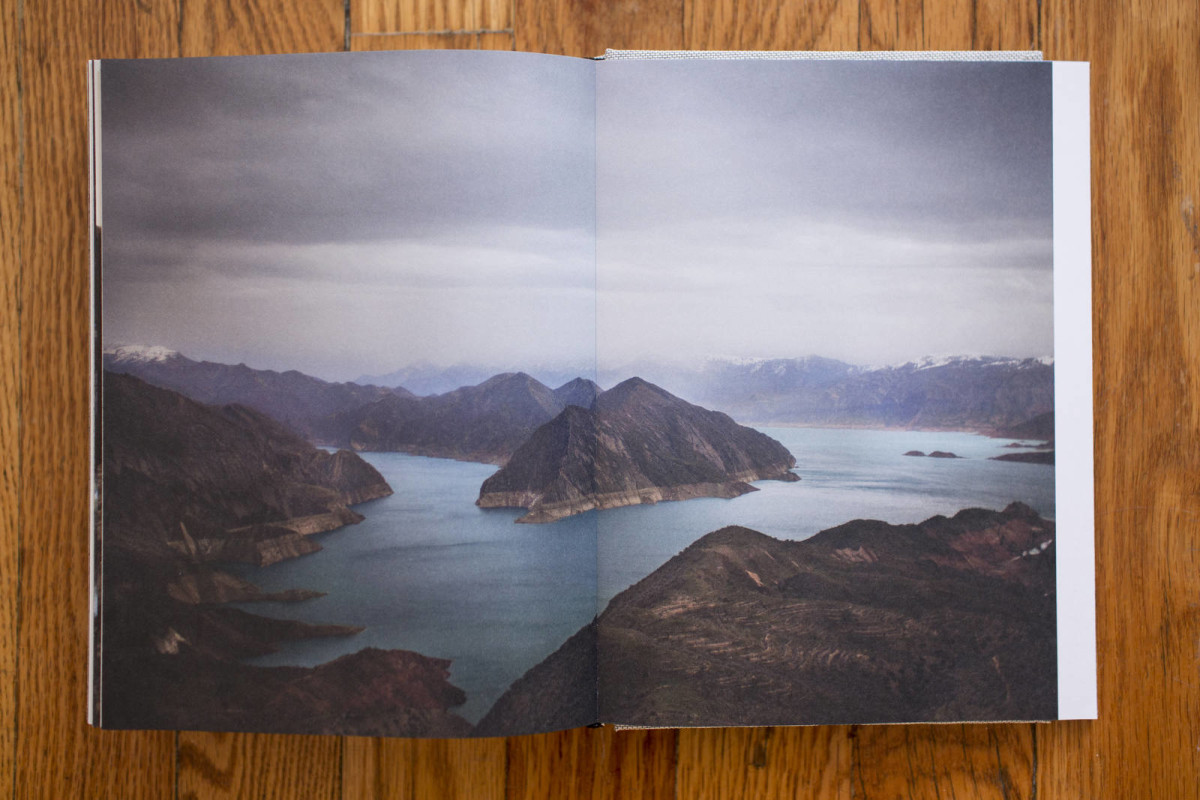

“The national borders in Central Asia, which didn’t make a lot of sense at the time they were drawn, make even less sense now, and everyone who goes there must make or discover her own map. In Two Rivers, seven geographically and thematically determined chapters follow the rivers upstream, from the sea to the mountains.”

—Elif Batuman

On sequencing:

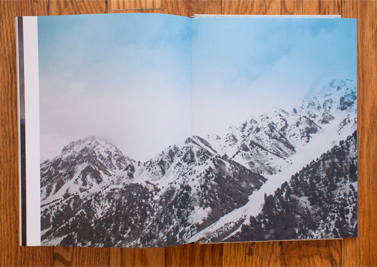

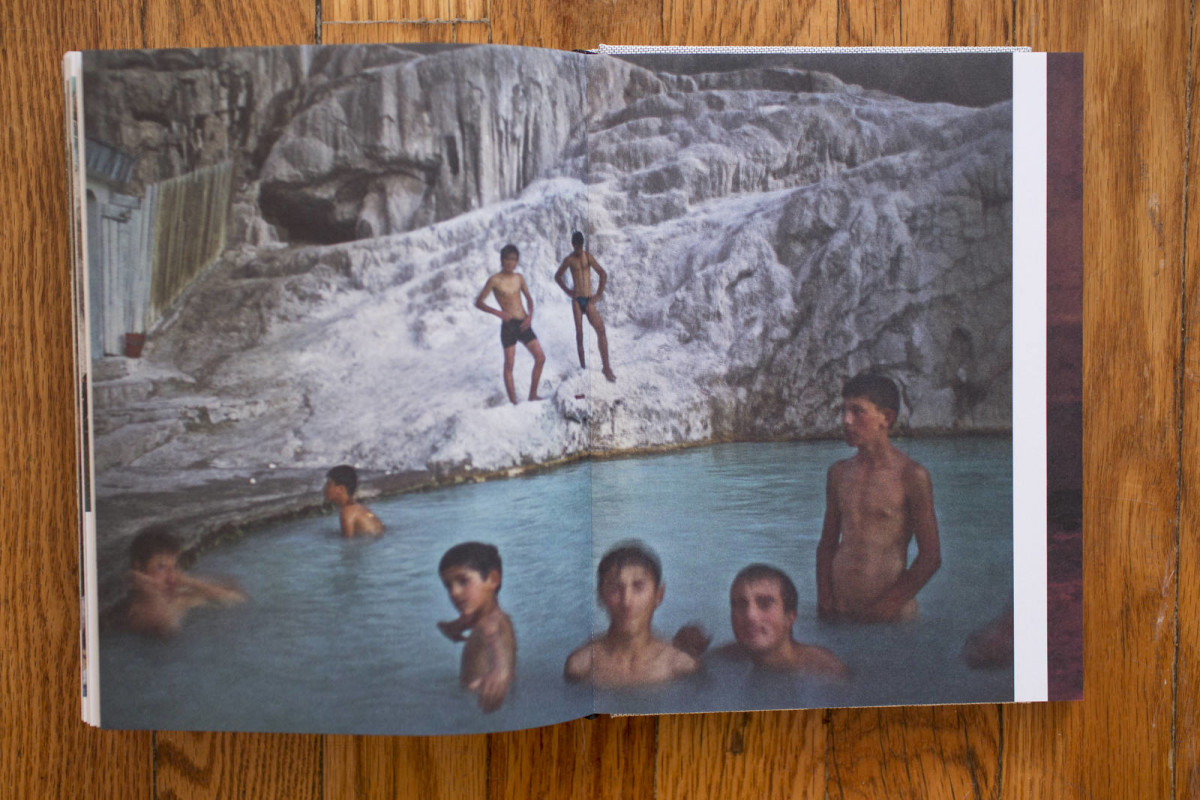

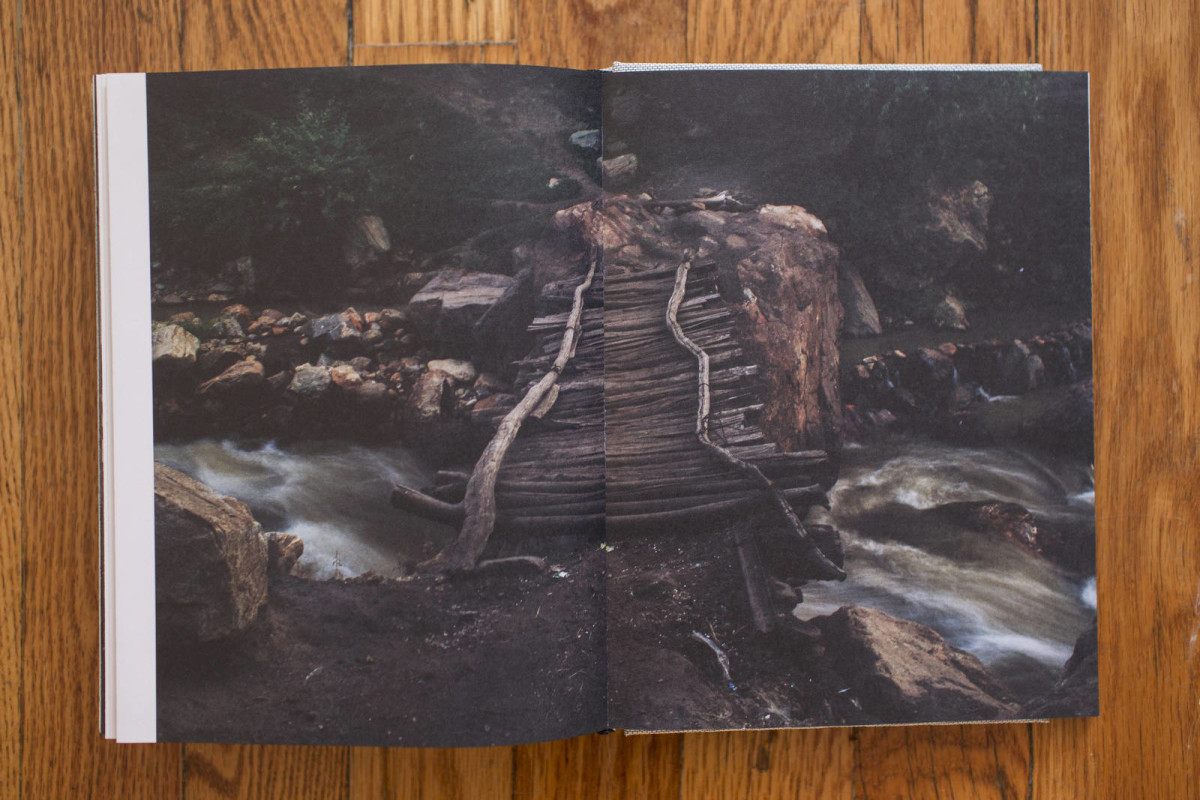

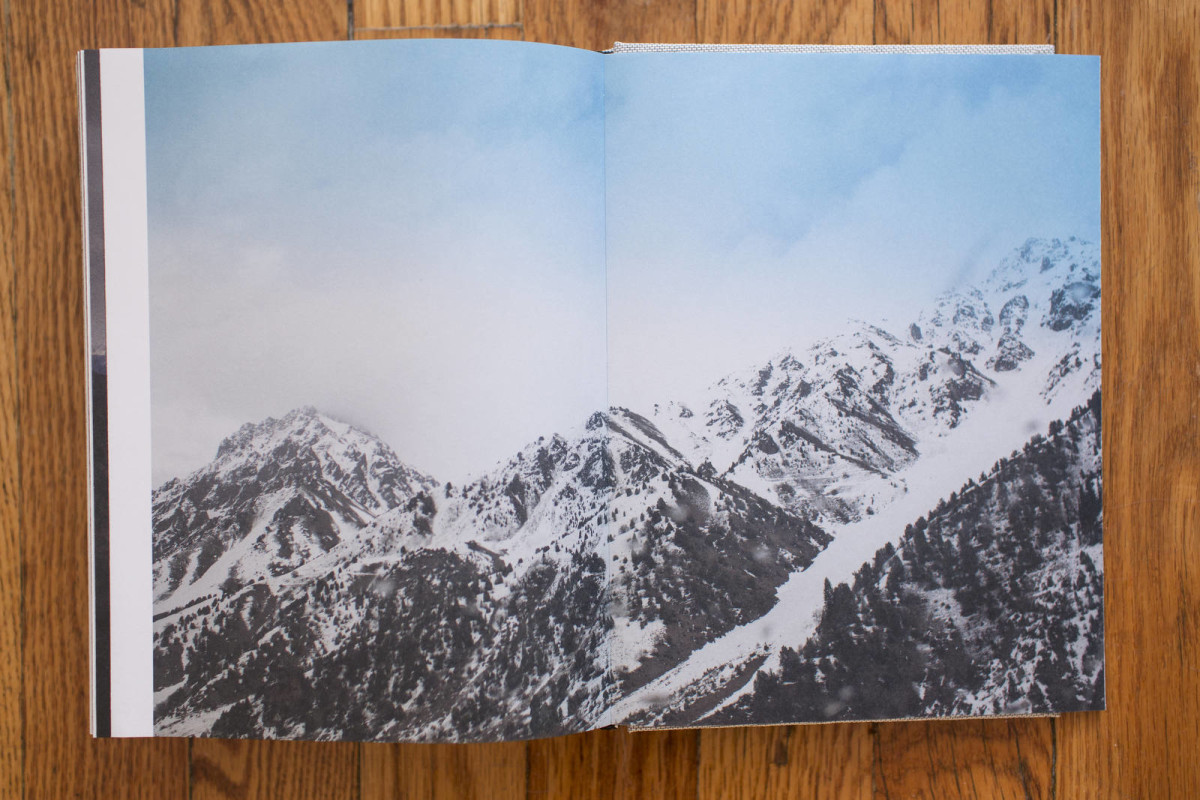

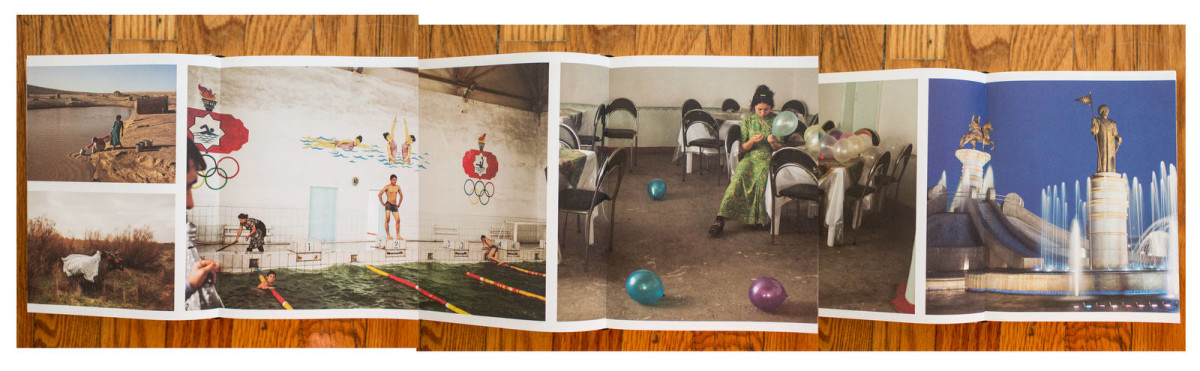

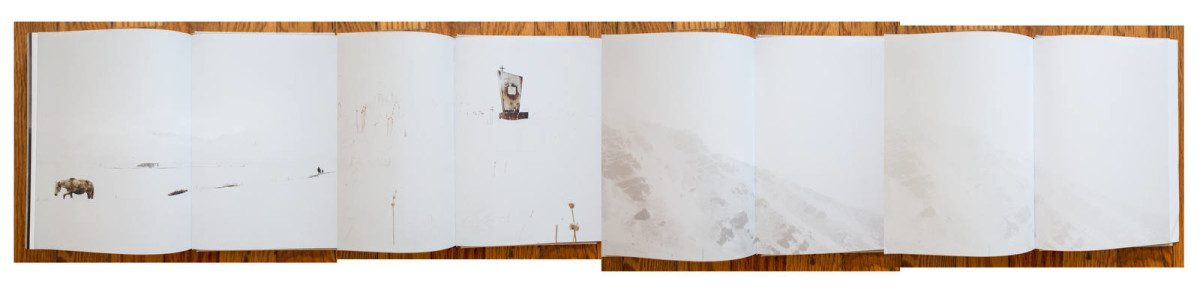

One thing Syb did that helped a lot was to reverse the overall sequence. I was trying to make it flow from the source to the sea, with the book ending at the tragedy of the dried sea, which is a down note. Syb suggested reversing it so the viewer is set up with the environmental story and dead animals right off the bat. You might expect it to dwell there, but instead you are taken on a journey upstream, so that the book ends in the mountains at the source, which you could also think of as a beginning—the white of snow, sky, air, a blank slate, emptiness, the end and the beginning. That is the crux of the book’s structure, and what I love most about what he did. Even though my project didn’t focus on the Aral Sea disaster, I had gotten stuck thinking the book had to stop there. It’s an interesting process deciding how to assemble the pieces of a story. The way you do it has a total impact on its outcome.

You are taken on a journey upstream, so that the book ends in the mountains at the source, which you could also think of as a beginning—the white of snow, sky, air, a blank slate, emptiness, the end and the beginning.

“Every aspect of this book, down to the way the photographs run over the edge of each page, belies a radical mistrust of borders.”

—Batuman

On the design:

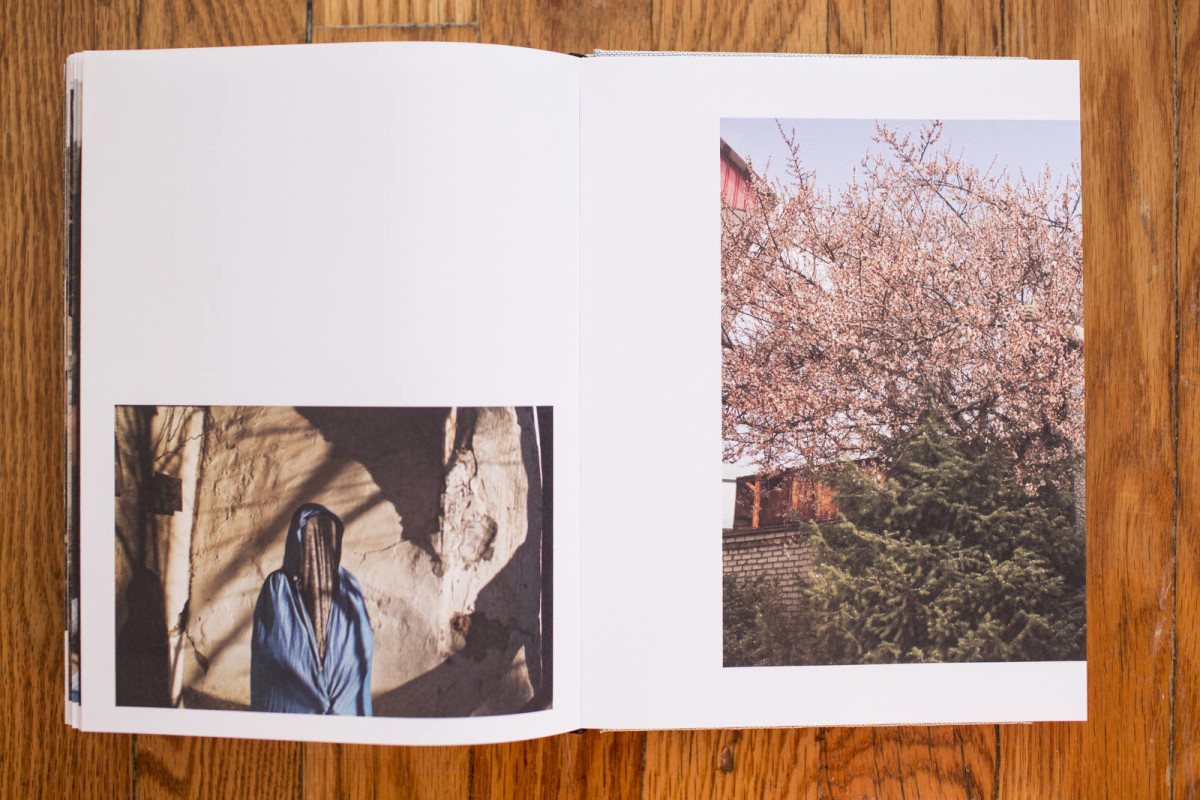

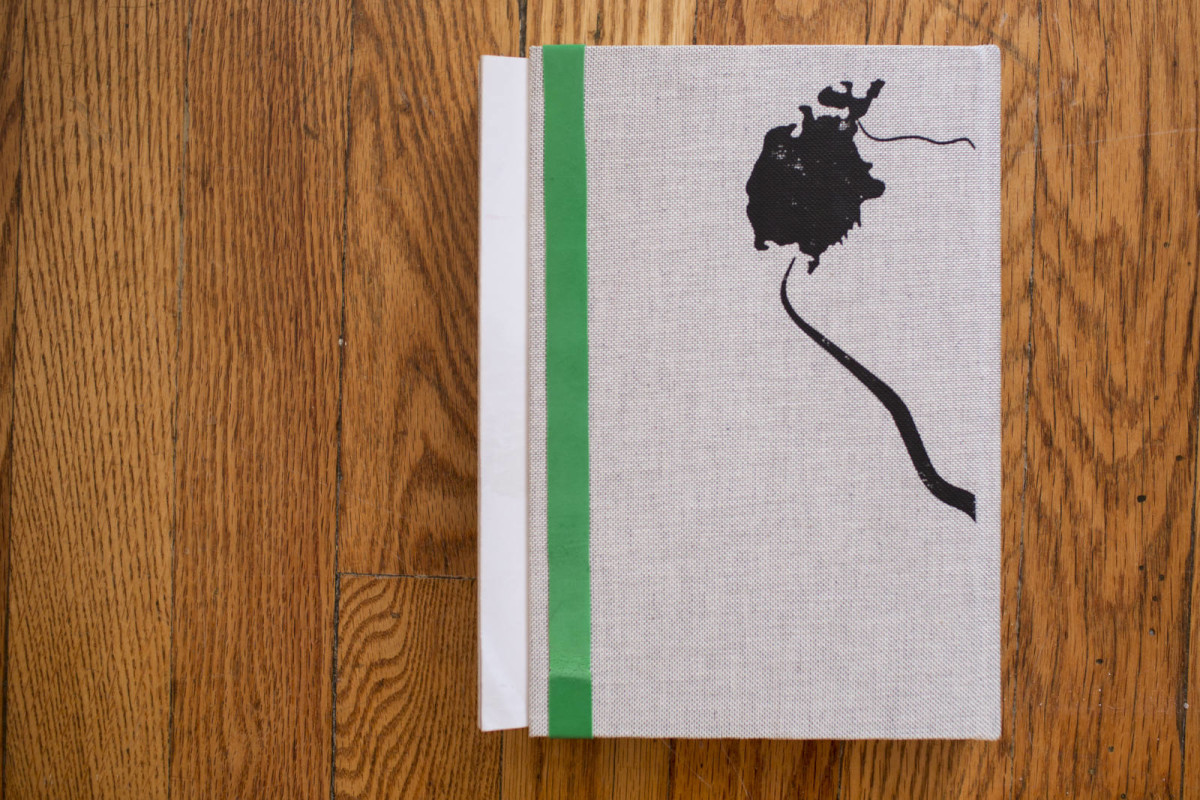

I liked the way Sybren Kuiper was using design to help propel and add more layers to the photographer’s narrative, and how the books were an object you had to dissect. I liked how the viewer had to turn the book in one direction to read something, then turn it in another to view a photo, so that you really have to actively read the book and the different tactile elements in it, not just flip the pages. It made perfect sense for that particular story. My project covered a lot of territory and contained different kinds of images—still lives, landscapes, moments, portraits. I thought Syb would be able to find a way to integrate them, to translate the content and ideas of the images into the physical elements of a book.

I knew he would come up with something that would shock me. When I saw it, I wrote him, “Wow, I need to sleep on it for a few days!” It was pretty radical, so I wanted to make sure I didn’t commit to it without thinking it through. I decided I should either go for the whole thing or start over—not scale back and go half way.

There are some people who thought it was really terrible to crop my pictures. “They’re beautiful! How can you do that to your pictures?” I listened to their responses and decided that that criticism was fine; I felt there were stronger reasons for the cropping.

On collaboration:

My gut told me it wasn’t a straight photo editor I wanted—it was someone who had experience making books. I would love to be able to do the whole thing myself, and maybe someday I will have enough experience with book-making to do that, but for this one that was not the case. The writing was a bit more difficult to let go of because I have this idea in my head that I can write. Both Syb and Elif have talents that I don’t, and I wanted to let them tap into those so that the book could be something more than I could make myself. I think people need to be allowed some creative freedom to make good work, so I tried to give both of them that, but to press back at times.

I wanted it to be carried out in a way that avoided trying to define or claim to “know” Central Asia.

On the text:

I initially wrote short texts for each chapter, and as I edited them, they turned into captions in which the sequencing and phrasing flowed (or attempted to flow) from one to the next, mimicking the layout of the images in the book. When I invited Elif to be the writer, she elaborated, and in a way, inverted that: using that format, but bringing commentary and ideas into it that are very much her own. I felt that it was important to have some text in the book to give context to the work, particularly since it was made in a place that is so unknown to most people who will view the book. But I wanted it to be carried out in a way that avoided trying to define or claim to “know” Central Asia.

On finishing the project:

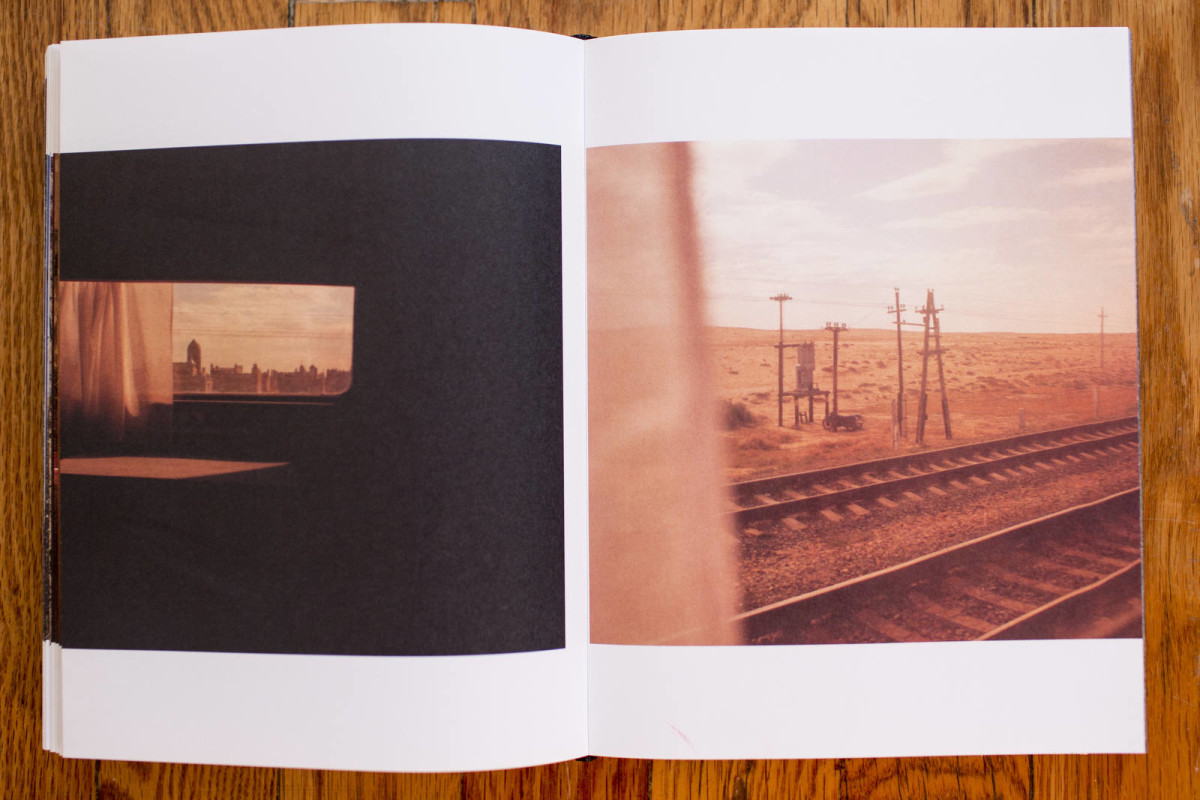

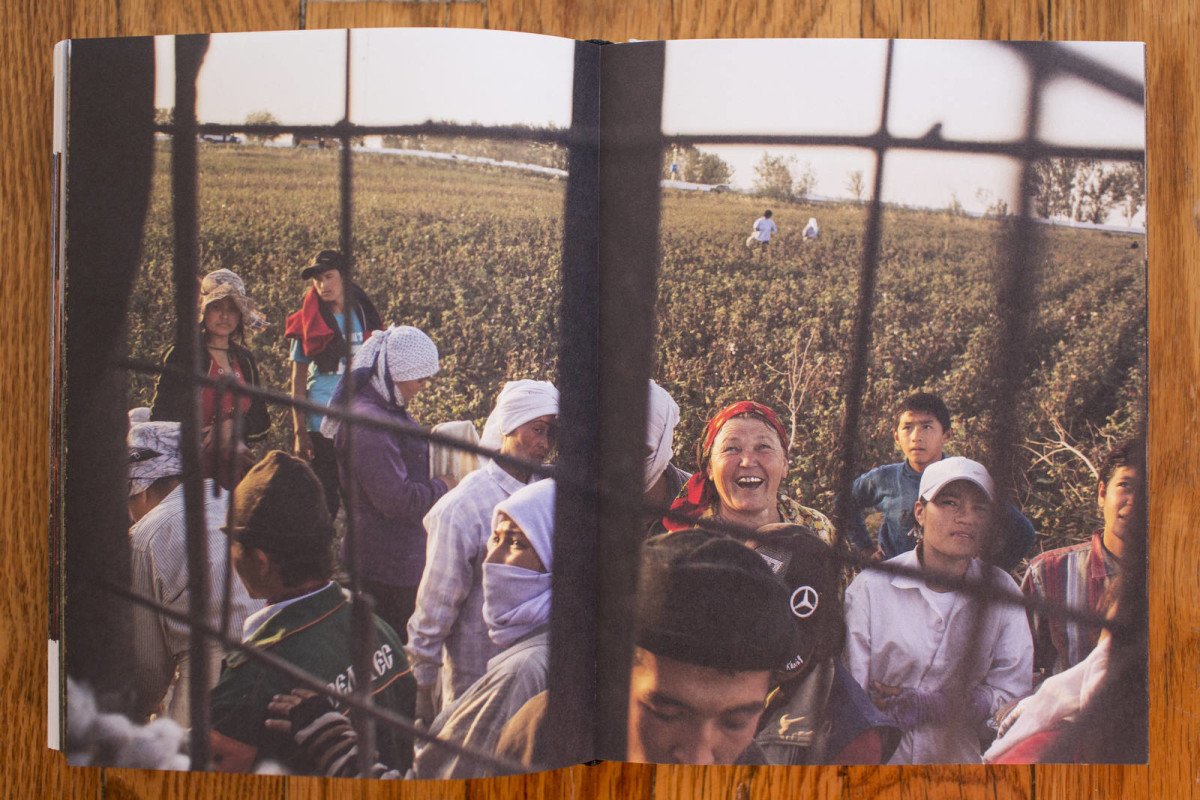

I made maybe fifteen trips to this area. It took a lot. And each trip needed a new visa. In Uzbekistan, you can’t stay for more than thirty days, and you have to get a new visa every time you re-enter. I’ve tried to go there with journalists and some of them are rejected. It’s difficult to get visas in Turkmenistan, too. The process of shooting there was also difficult, and I think the design of the book reflects this. It’s not a natural flow going to try and work there and make pictures there. It’s full of frustrating barriers.

I decided the shooting was finished simply because I felt I had pushed the ideas in the project as far as I could. I think the impulse to move in new directions came along with that.

The best thing that happened was at the end of my shooting time there. I met this group of photographers in Tashkent, the capital of Uzbekistan, twenty people or so, and I showed them my work and they asked a lot of questions and we had a dialogue about the work and the ideas. Then they showed me their work and their projects. It felt fantastic to have a sustained and intelligent conversation with creative photographers in Uzbekistan, especially because a lot of this work was unofficial and almost in secrecy. I was a tourist. I wasn’t openly able to do this research, and a lot of it was on the sly. This was one of the reasons that I wanted to wrap it up—because it feels kind of dirty to not be able to be open about what you’re doing. To find this group of photographers with whom I could talk openly was a great finale.

We like to categorize: “This is what Russia is like, and this is what Islam is like.” I liked spending the time in these places, letting them blend together. The world isn’t so easily categorized.

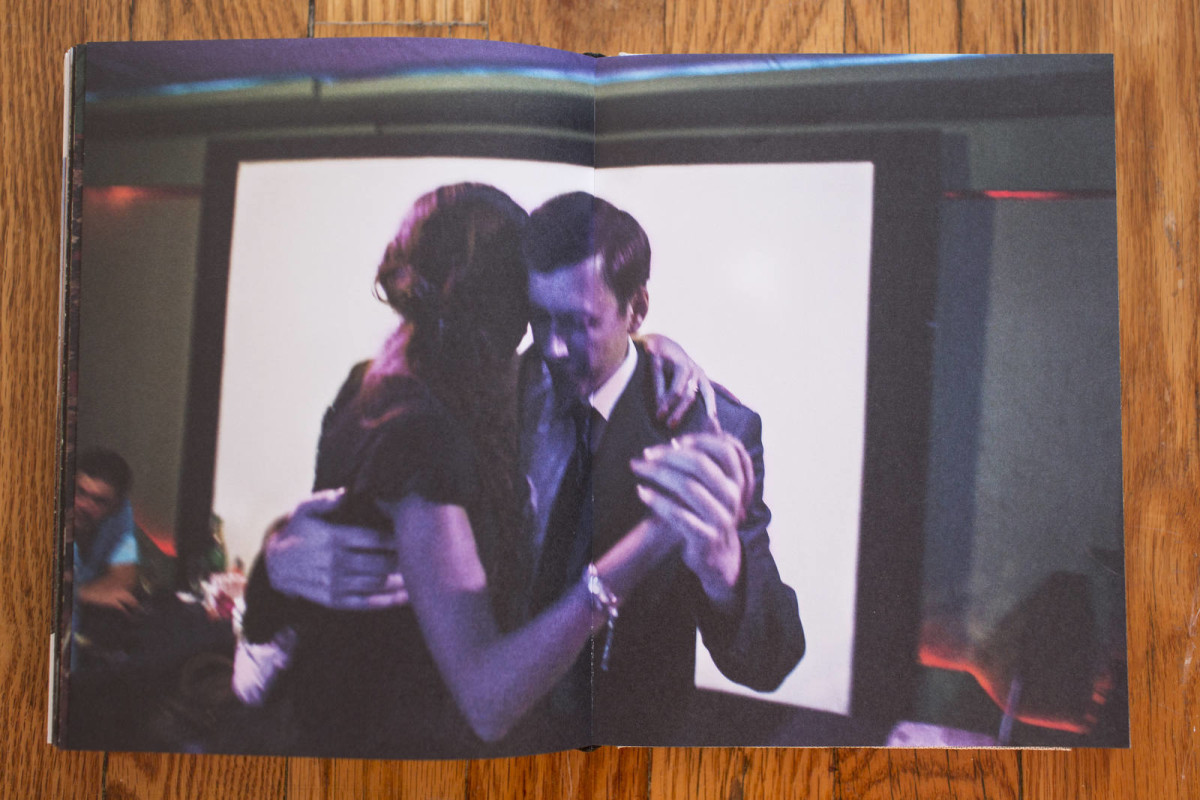

One of the things that really drew me to Central Asia was this intersection of cultural characteristics that seem like they just don’t go together or would never go together, like mixing Islam with Russian culture, with some Chinese elements. We like to categorize: “This is what Russia is like, and this is what Islam is like.” I liked spending the time in these places, letting them blend together. The world isn’t so easily categorized.

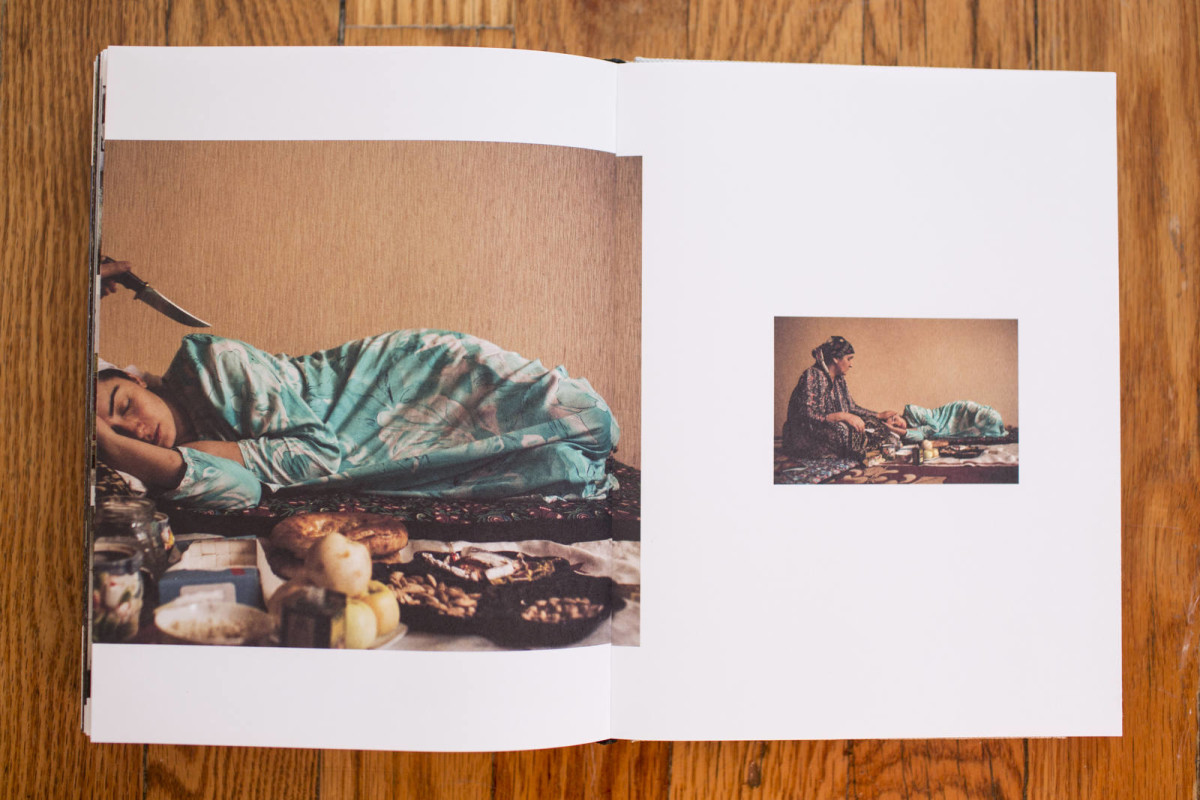

“Drake’s pictures blur the line between us and them, here and elsewhere, implicit in all travel photography. The two categories unfold and disappear into a rich spectrum. In one photograph, a Tajik shaman sits on the floor, holding a dagger over the body of a sleeping girl; spread before them are a box of sugar cubes, a plate of yellow apples, two flat loaves of Central Asian bread. The women’s luminous faces, the still life of symbolic edible objects, are reminiscent less of a National Geographic spread than of a Vermeer interior. They suggest not anthropology but mimesis: the representation of daily life.”

—Batuman

Carolyn Drake often works as a photographer for The New Yorker and National Geographic. She is the recipient of the Lange Taylor Prize, a Fulbright grant, and a Guggenheim fellowship. Two Rivers is her first book.

Elif Batuman writes for the New Yorker and is the author of The Possessed: Adventures with Russian Books and the People Who Read Them.

Glenna Gordon is a documentary photographer working often in West Africa.