Her bicycle had a rack over the back wheel that was sturdy enough to sit on. I had to keep my legs out of the way and hold, just with the fingertips, to the underside of the saddle. Every time we turned or met a bump, I placed a hand on her waist. She pedaled, rising and sitting, the wind running through her dress and hair. I caught a perfume, hints of soap and shampoo, and that other thing that was hers alone: her body and days and nights. She wanted to take me to the ninth arrondissement. I had just moved to Paris, hadn’t been there a week. We stopped on the way and ate salt beef sandwiches standing on the pavement, then raced across to a library she wanted me to see. I don’t remember what it was called and have forgotten since how to find it. We walked in, doing our best to keep quiet, to slow our breathing down. The windows stood high and turned in half-moons at the top. Too many books, too few people bent over them.

We went on, there was another place to go. I watched her back, her lungs working hard, and decided then that it was okay to hold on to her. She stopped in the middle of an unremarkable street, looked up towards one of the windows, and said, “That’s where my grandma lived. The place she moved into when she first arrived to France.” She mounted the right pedal and pushed forward. I held on to her with both hands. The wheels turned and the wind was a lovely thing.

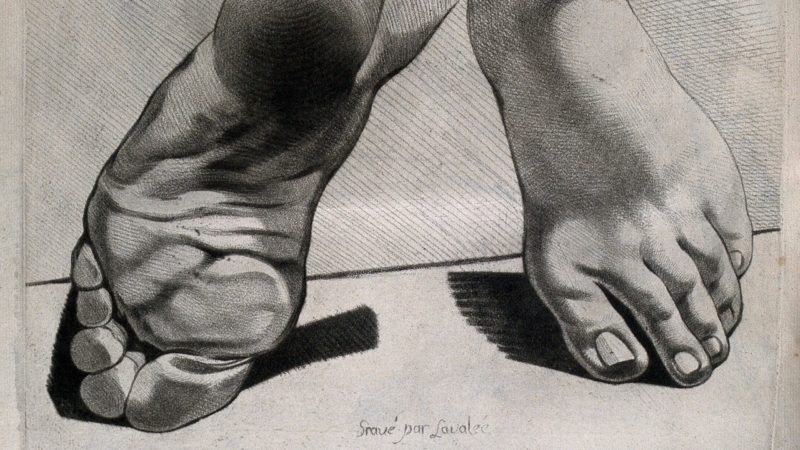

We went back to her place. She opened all the windows, started making tea, and we sat cross-legged directly on the naked floor, the wood cool against our thighs. Her knees were round and strong and delicate. Although they seemed one color, I began to notice beneath her brown skin a vapor of pink, a deep green vein passing, the distant blue of flesh. Her bare feet showed the slight stain of her leather sandals and the halos that the straps left around her ankles. Her toes were open and free. A breeze blew softly across the room. She was making Japanese tea. Everything had to be precise and we needed to be patient, she told me. She smiled as she said it. I wanted so much, with an ache and a burn, for her to tell me something she had never told anyone before. Just then I saw, hidden in the cleft between her first and second toes, a tiny pearl of dirt, rolled up by the day, nestled in hiding.

The tea was ready. She poured it and we drank it slowly in silence.