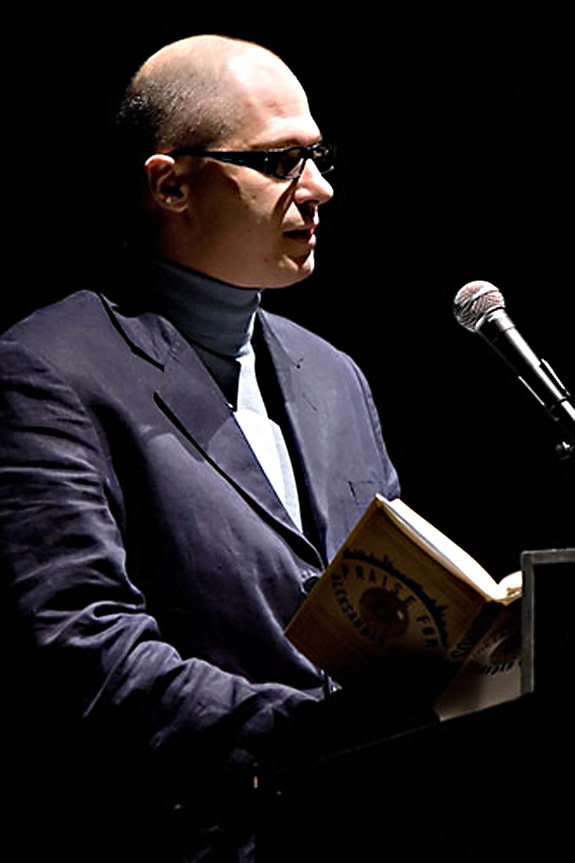

Aleksandar Hemon—Sasha, as he likes to be called—left his native Sarajevo for Chicago on a cultural exchange program in 1992, just as the siege began. He resolved to settle, mastering English while he canvassed for Greenpeace and watched his hometown burn on the news. Once a journalist in Bosnia, Hemon wrote his first story in English in 1995 and within a decade received a Guggenheim Fellowship and a MacArthur “genius grant” for works penned in his new language.

His 2008 novel, The Lazarus Project, began as an investigation into the true story of an escapee from the pogroms of Eastern Europe, who was shot by Chicago’s police chief in 1908. Photos of a police captain posing with the corpse are included in the book, which Hemon calls “an Abu Ghraib novel.” It is narrated by Brik, a columnist and Bosnian immigrant to Chicago, who wins a grant to travel to Moldova and finally to Sarajevo to research the worlds that both he and Lazarus left behind.

Unconcerned with the boundaries between fiction and nonfiction—“There’s no such difference in Bosnia,” he says—Hemon’s work investigates the many uses of narrative, from jokes and gossip to the way states create national identities and individuals struggle to maintain coherence. “In some way there is no real life,” he says. “It’s always the story of your life that you’re living.” Among the most deeply felt of these explorations, the essay “The Aquarium,” from his forthcoming nonfiction debut, The Book of My Lives, describes experiencing the death of his one-year-old daughter as his three-year-old acquires language and invents an imaginary brother. The book’s dedication reads, “For Isabel, forever breathing on my chest.”

I met Hemon at his agent Nicole Aragi’s apartment in Chelsea. When I arrived, I found him in front of a large TV discussing soccer coaching strategies with the Somali novelist Nuruddin Farah. Hemon led me to a long, heavy wood table and we sat directly across from each other. He nervously fingered a plastic bottle cap, bouncing it off the tabletop over and over again as we talked. His presence was large and looming, and there was a controlled aggression in his posture. He was serious but laughed easily, adamant but occasionally self-mocking. “There’s a very simple rule of writing,” he told me. “It’s all shit, until it isn’t.”

—Brad Fox for Guernica

Guernica: What do you make of the story that Sasha Hemon came to America, couldn’t speak English, and then two years later sat down to write The Question of Bruno: Stories?

Aleksandar Hemon: That’s the great American story [laughs]. It complies with the story of immigrants who came through Ellis Island: they were nobodies—half-human somehow. They had potential, but of course they couldn’t do anything with it over there, because it wasn’t America, so they came here, and suddenly they bloomed.

I don’t know the numbers, but roughly half of the people who came through Ellis Island returned home. They came here to make money, not to make history.

Guernica: But you didn’t return home?

Aleksandar Hemon: I could have at a certain point, but I didn’t. Life had started here. Chicago is not a bad place to live. But the usual story of immigration is the happy fulfillment of human potential in America that is not available anywhere else—it’s propaganda, really. It’s more complicated than that.

Guernica: Did you simplify your own story in order to make yourself easier to understand?

Aleksandar Hemon: If I did, I didn’t do so deliberately. I hope I didn’t. I went to see a doctor, and he was asking me routine questions in order to create my health file. Everything he asked was a yes or no question. He’d ask me, “Do you eat meat?” I’d say, “You know, I don’t eat some kinds of meat, but I eat other kinds, but even so it’s not so often, depends on the day.” He looked at me like I was a complete lunatic. I realized that I could not give a simple answer. Everything was fucking complicated. I realized that, responding to anything anyone would ask me, my position is always, “It’s a little more complicated than you think.” In that sense I am psychologically disinclined to simplify anything about me or anyone else. My ex-wife once told me—and she was scolding me—“You only like complicated people.” And I told her then that everyone is complicated, but for some reason—convenience or laziness, political pressure, ideological pressure, identity pressure—people like to simplify themselves.

There’s this instinct to strive toward simplicity: simplicity is valued in this country… But much of this craving for simplicity is fake. It’s deliberately eliding the complicatedness of everyone’s life, which is why nationalism and Bush-like fantasies are so comfortable.

Guernica: Are you lazy?

Aleksandar Hemon: Yes, proudly so.

Guernica: But you tend to think out your novels a long way in advance.

Aleksandar Hemon: That’s a nice way to put it. The other way to put it is: I think about it until I have to write it. There are many things I think about that never get to the point of becoming serious. In other words, I try to talk myself out of writing, sometimes for many years, and when I run out of arguments, I write.

Guernica: Are you actually working when you’re thinking?

Aleksandar Hemon: When I say I’m thinking about it, it’s not that I sit like a Buddhist monk and focus on the story and envision the whole structure. I think about the story while I think about other things. This is an important part of the process: I look at it sideways. If I look straight at it, it produces nothing other than what seem like complicated, brilliant designs that fall apart the following morning. In some way stories mature when you’re not looking.

I have operating theories about this. I’m not nervous if I think about something for nine years and then I don’t write it. Even if it fades it doesn’t concern me. It’ll come back if it’s worth it. It’s a kind of selection process by means of laziness [laughs]. That’s why I’m proudly lazy. It’s a method.

Guernica: How conscious are you of doing this?

Aleksandar Hemon: It’s not that it’s codified or replicable. It’s so internalized, the way your mind works in relation to anything—it’s a process, but then it isn’t. It’s working all the time.

Guernica: Did you ever have an idea you thought was too big to tackle?

Aleksandar Hemon: I just let them sort themselves out. I defer starting. I say, “It’s too big. I don’t want to do it,” or I say, “It’s not that it’s too big, but I can’t start now. I’ll see about it when I have time,” and in the meantime I’ll write soccer columns, or I’ll write another short story. But some things stay around. I constantly—and it’s compulsive—think up stories. I’m on the train, and I see something, and I imagine a scene from a hypothetical story in which this person is doing what I am seeing. This happens every single day of my life, in various ways. I remember one better than others: I was in a coffee shop, and there was a couple, and there was a bee flying around the woman’s head, and the man shooed it away. But for some reason—I had nothing better to do—I imagined a scene where he fails to protect her, and the bee stings her, and all kinds of problems ensue.

Guernica: So you write only when inspiration comes?

Aleksandar Hemon: I don’t believe in inspiration. I write when I can’t avoid writing anymore. Danilo Kiš said, “I start writing when I overcome my disgust with literature.” I end up writing something every day, since I develop six or seven things at the same time—soccer columns, this and that. I’m constantly longing for more reading time, so I’ll skip writing for reading. Sometimes I have a deadline, and I say, “Ah, fuck it, I’ll just read a memoir of an inarticulate soccer player.” Sometimes I don’t write at all. Someone once asked me, “What do you do when you’re not writing?” And I said, “I idle.”

Guernica: How do you feel about teaching?

Aleksandar Hemon: I don’t like having a teaching job—office hours and conferences and committees and bosses and all that—but I tend to enjoy teaching, and I design the course in such a way that there’ll be pleasure in that. I’ve never had a stupid student in my life. I never look down on my students. I never thought, “Look at these people.” I might argue with them and I think that some of them might have misconceptions—that they might be infected by the intellectual laziness that is the foundation of American popular culture, and of capitalism, if you wish. But part of my job as a teacher is to work with that—against that.

Even if you tried to extinguish your personality, what is left in the story will reflect it, perhaps by its negation. Our lives provide the bricks from which we build these cathedrals.

But I do tell my students “You don’t have to write.” You have to go through things in life. To write has to be related to a drive inside. In writing class, it’s easy to fall into the trap of saying, “Oh, this draft is a little better than that one. Anything can be incrementally improved.” But there’s a very simple rule of writing: it’s all shit, until it isn’t. Steady, incremental improvement does not work in art. Some people wake up one morning and they write a fucking great book. Or they write shit for twenty years and somehow, miraculously, one day, because they have made all the mistakes they could have made writing shit, they write something that contains no mistakes. It’s fucking perfect. I’d written shit for many years. Then I came here and looking through what I’d written in Bosnia, I found a paragraph, randomly, that was not shit, and I thought, “That’s how I want to write.”

Guernica: What was it about the language of that particular paragraph?

Aleksandar Hemon: It had sensory detail that touched me. I was writing for a magazine and I’m prone—especially when I write journalism—to this tone of arrogance and pontification [laughs]. This was devoid of that. It was actually felt.

Guernica: When I think about your work, from Question of Bruno and Nowhere Man up to now, there are these complicated vectors moving together. It seems to me that you know mathematics.

Aleksandar Hemon: It’s strange that you mention it. When I was in high school, I was in a special math class. I was infatuated with physics, particularly nuclear physics, Einstein, and the Big Bang. I read a lot about black holes. And partly because I’m so lazy I thought you could do all this just by looking at the sky and thinking up universes. It didn’t seem like hard work when I was a kid, so I enrolled in this class.

Guernica: Do you think there’s something mathematical or algorithmic that goes into the art of writing fiction?

Aleksandar Hemon: The mind is complicated and you can’t trace the roots of its processes, but there is something about mathematical and algorithmic patterns that I like to recognize in things.

You devise ways to tell a story that complies with your sensibility. Style and method are really extensions of your present sensibility. The beauty of literature—also its limit—is that it is inescapably personal, even if you’re writing science fiction. Even if your story takes place on a different planet, it comes out of your personality, your personal experience, your sensibilities, your interests, your passions, the whole of you. Even if you tried to extinguish your personality, what is left in the story will reflect it, perhaps by its negation. Our lives provide the bricks from which we build these cathedrals.

Guernica: Your new collection, to be released next week, is called The Book of My Lives. Is it a kind of memoir?

Aleksandar Hemon: No. Memoir implies the need to reveal something about yourself—to recount your life for educational purposes. In the olden days, a memoir was something written by Churchill and people like that, because they had a grand experience and considered it useful for future generations. And then it became what it became—a public purging in which other people have the chance to judge you and then forgive you, perhaps learning something from your sorry example. That was not the impetus for me. My impetus was to tell stories.

I spend a lot of sleepless nights worrying about the world in which my daughters will live, which will be flooded, to say the least. But as far as storytelling, it’s always about the problem I have at hand, “How do I get out of this fucking hole.”

The funny thing is that in Bosnia there are no words that are equivalent to fiction and nonfiction. From the storytelling point of view, the difference is artificial. What if the umbrella term for all that is story? It is my belief that we as human beings have a need to tell stories—I think it’s evolutionary. So you can think of the short story as a literary form, or you can instead think of stories. For instance, to me, this complies with the definition of story: I went to buy a bottle of water and got lost. You can tell that story to your friend, and it can last for four sentences and contain no great drama or messages, but it is still a story of what happened. I imagine in the olden days, the cannibals would come back and say, “We saw a nice plump group of people in the woods. Come with me and bring the spits.” They would tell people what they saw. Now we think in terms of information—if you have information you’ve got the world by the balls. But we have to convert information into knowledge in order to make it humanly useful.

There’s something in psychology called the narrative paradigm, which essentially means that we think of our lives as stories in which we are the main characters. And there are studies that have shown that we make decisions, ethical and otherwise, based on the way we imagine ourselves as characters in the stories of our lives. In other words, if we imagine ourselves brave or crazy or open, we’re more likely to make decisions in a given situation based on how we imagine ourselves, whatever the facts may be. We imagine ourselves as constitutionally possessed of good intentions, so that the outcome of our actions is always morally solid.

And this is also how memoir works: I’ll tell you a story about myself and I’ll edit out all the things that don’t comply with what I think of myself. So story is the overarching or underlying template. It is the axiomatic category—the essential way to organize human knowledge.

People will always tell stories. The publishing industry might vanish, but not stories. There are already new ways of telling stories. The way I think of my work is that I have to think up the way to tell a story, starting from scratch. The changes in the industry concern me in a general way because I think civilization is doomed, and I spend a lot of sleepless nights worrying about the world in which my daughters will live, which will be flooded, to say the least. But as far as storytelling, it’s always about the problem I have at hand, “How do I get out of this fucking hole.” And there are always many holes, until there aren’t.

Guernica: Counter to your laziness, it seems, is a sense of outrage. The Lazarus Project, for example, with its images of captured anarchists, is in part a reaction to Abu Ghraib.

Aleksandar Hemon: I wrote much of the book in Sarajevo in six weeks in the summer of 2005. I wrote pages and pages of rants against Bush, against the imperially delusional American policies. I just let it go out of anger and passion. And out of passion comes an enhanced language. But then, later, I cut a lot of it, and left only what would comply with Brik’s character—with his sense of despair, not just with his righteous anger. His anger is not only politically justified, it’s part of his displacement. He’s angry at his wife, he’s displaced, he’s pissed, he’s lost, so his anger is related to who he is, rather than just to what I think. One of the upsides of writing pages like that, once you write them, is thinking, “Now what? What do I do with this? I ranted and then what?” I’m capable of recognizing that it’s obsessive and that it has value only if it’s given to a character.

Guernica: In the early 1990s, you saw people that you would never expect become nationalist in the former Yugoslavia. I wonder if it was similar in the U.S. after 9/11?

Aleksandar Hemon: There were some similarities, which were scary, but there were also some dissimilarities. In retrospect, I realize I was delusional in the early 90s in Sarajevo. I was young and there were many misconceptions I depended on. For one thing, I believed in a kind of urban solidarity—in a fault line separating urban from rural. I had a notion that if you listened to rock ‘n’ roll, you had a bond with others that couldn’t be broken. The people who listened to rock ‘n’ roll, I thought, were bound together against the people who didn’t listen to rock ‘n’ roll. That, of course, didn’t work at all. Your taste in rock ‘n’ roll does not say anything about you, morally or otherwise. My misconception was closely connected to the misconception that art makes you better. That is: you expose yourself to it, you read books and read Shakespeare and watch all the right movies, and when the tough time comes, you’re likely to make the correct decision because you were ennobled by art. There’s no basis in reality for that at all. There’s no connection between consumption of art and moral stamina at all. So I, like so many people from Sarajevo, was surprised when our friends and other people betrayed this urban solidarity. It’s not just that they chose an ethnic side—they chose the ideology of nationalism of their ethnic side. And that ideology was no longer theoretical: you’d have to join the armed forces of your nation and participate directly in the atrocities they might be committing.

That’s a different continuum from the purely theoretical jingoism that happened here: “Let’s just attack Iraq.” Iraq is still an abstract concept. Arabs are a complete abstraction in the propaganda world and all the death and destruction is completely unreal to Americans, particularly now that we’ve withdrawn. It’s just on TV. Not that it’s better to be a rabid nationalist who’s willing to take up arms, but if you’re not, there’s kind of a childlike quality in it.

Guernica: In Bush’s first visit to Ground Zero—with his megaphone, surrounded by men shouting, “U.S.A.! U.S.A.!”—it couldn’t help but remind you of Milosevic’s early rallies.

There was this willful self-delusion on the national level. We were lied to, but we wanted to be lied to—we liked it when they lied to us. It showed us a kind of respect.

Aleksandar Hemon: I think that in the first sentence that Bush uttered after the towers went down—certainly it was in the first speech that he gave—were the words, “Freedom itself was attacked.” I thought, “Freedom? Fuck me!” If he can abstract this—if he can turn this into a cliché within forty-five minutes—we’re fucked. Because if he can completely ignore this reality, then there’s no limit.

This propagandistic abstracting in the U.S. could partly be the reason why the Bush years were so quickly forgotten. The lies, the crimes, Abu Ghraib—all that is forgotten. It was like a happy summer of eight years when everyone went crazy and then the summer was over and school started again. Everyone forgot what they thought or did, forgot their drunkenness and the patriotic parties with a lot of Budweiser. We invaded two countries, and there was this blatant lie and there was a torture camp or two operated, and there were black sites. The government ran illegal programs and Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo. But once Obama’s elected, it’s school again and not a big deal. There was a buffer between the moral choices of patriotism in the early aughts and the consequences. In Bosnia there was no buffer. The people that chose sides—particularly the Serbian and Croatian sides—participated actively in what was a vast crime, no matter how distant they were from the front lines. It’s difficult for me to understand how it was possible to live under the Bush regime for eight years and then just roll over and do other things.

Guernica: During the ten-year anniversary of 9/11, there were many solemn tributes to American bravery and perseverance, but very little remembrance of the public support for the invasions and abuses the attack was used to justify.

Aleksandar Hemon: I think it’s interesting, from a creative point of view, to have witnessed the loss of consciousness on a national level and on a cultural level—Bush had 91 percent support in the polls after 9/11. We wanted to kick some ass! And we’re just hankering for an excuse. There was this willful self-delusion on the national level. We were lied to, but we wanted to be lied to—we liked it when they lied to us. It showed us a kind of respect. Bush and company used this hankering brilliantly. And this willingness to believe in comforting mirages, to accept the delusion of power, to desire having the biggest dick in the world—I don’t think fiction needs to redress this ethical collapse and change everyone’s mind, but this ought to be interesting novelistically. How did this happen? Someone should be writing a novel about this.

Guernica: Trying to stage complicity?

Aleksandar Hemon: Trying to address that willingness to comply with the given narrative. What we do in fiction is that we construct fictions. Here was a major piece of fiction constructed in front of everyone. How did they do that? What did it do to us?

In some way there is no real life. It’s always the story of your life that you’re living.

Everyone in Sarajevo has a story about betrayal—every single person. We were friends and we shared everything, and suddenly they turned away and left us. Some became outright killers. It was a complete mystery. Everyone asked themselves, “How could our neighbors do this to us? How did it happen?”

While there’s some continuity all along, the very need to establish or restore continuity is related to storytelling. You have to elide and edit your life so as to fit this new development, to restore the continuous narrative of your life. In some way there is no real life. It’s always the story of your life that you’re living.

If you find yourself as a person in unfamiliar territory, you will grasp on to what is already familiar. In terms of language, if you do not understand what something is, you will look for a comparable concept or similar concept and apply that label. We apply the language that is comforting and comfortable and familiar in order to grasp that which confuses and scares us. That is the first step toward cliché and stereotype, as they’re comforting devices. They reduce the confusing world to the already familiar. We’re always smoothing out the bumps of actual living to turn it into narratable life.

I believe people are much more complicated than they can handle. There’s this instinct to strive toward simplicity: simplicity is valued in this country. Simple people are somehow better and more honest—which is why a simpleton could be president. But much of this craving for simplicity is fake. It’s deliberately eliding the complicatedness of everyone’s life, which is why nationalism and Bush-like fantasies are so comfortable. United we stand. One of the things that drove me so crazy after 9/11 was: why exactly do we have to stand united? Why exactly? Did they suspect that Minnesota would somehow start supporting Al Qaeda? What was the fucking danger of not standing united? But standing united was comfortable: here we are, all our thinking simplified into patriotism. I’m more comfortable—and yes, I think it’s been beneficial to my writing—with complicated stuff.

Guernica: Are you embarrassed to be living in America?

Aleksandar Hemon: No, because I live with people. I cannot think of a country in which I would be happy with the government and dominant ideology and available propaganda. You can think of America’s flags and lies and occasions for invasions, or you can think about America, well [indicates us]: here it is.

To qualify a little bit more: It’s a little bit more complicated than that [laughter]. What I don’t like about America is not necessarily an American thing; it’s a capitalist thing. This is the Vatican of capitalism. Wherever there’s capitalism there’s this inclination toward simplicity. There’s also a human need to process complicated things by turning them into something else. I don’t think that everyone should have a philosophical answer to any given question. There are things that need to be done. You don’t want your neurosurgeon to have doubts about the meaning of it all while he or she is operating on your brain. What is unfortunate in this country, in relation to literature and writing, is that it complies to such an extent with the laws of the market. Anything that might come under arts should not be subject to the whims of the idiotic market because the market’s stupid, and it gravitates toward simplicity—towards essentializing things so they can be sold.

I like to blow up this notion that all we have to do as writers and artists is represent reality, which is presumably solid and self-evident, with no negotiation of the gap between myself and the world, between this body and this space, which needs narration to close it. You have to figure out a way to cover that gap. It seems self-evident because we do it routinely. It’s a condition of being conscious. But what fiction and art can do, particularly narrative art, is construct consciousness—in a sense, we have to do it for the first time, every time. We, as writers, have to figure out a way to create a consciousness in language. It’s crazy even to attempt to do that.

Guernica: It’s like trying to maintain two contradictory ideas.

Aleksandar Hemon: Yes, to reconcile all these simultaneous selves. I mean, there’s a social and human necessity for some kind of continuity, but it’s not axiomatic and not something you’re born into; it’s something you have to work at. And one of the ways to work at it—perhaps the best—is storytelling: telling stories about yourself to others, telling stories about yourself to yourself, telling stories about others to others. From what I’ve read, one of the many conditions that have to be met for a brain to become a mind, and therefore have consciousness, is ‘the analog I’ around which all the simultaneous inflow of sensations and stimulations are reflected and organized. So that as I talk to you here and all these things around us are happening simultaneously, I can tell someone, in a sentence, it was I that sat with you and talked.

Guernica: In studies I’ve read about the neurology of meditation, one thing that happens is that key brain centers quiet. One of these controls the function of physically separating self and other so that you don’t bump into things. When that quiets, what the brain recognizes as self becomes limitless in the most concrete sense—and the result is an expanded, encompassing sensation.

Aleksandar Hemon: That makes sense: the analog I and the I become one. There’s no distinction. Because the moment there’s a split between them, you don’t have an I but a self—not even a self but the beingness of me, and the I—the space of it—is the interiority. You need to narrate the gap in order to cover it. I’ve never meditated for a moment in my life. I don’t know how it works, but I suppose the gap is closed. But one of the things you have to do to put yourself in the meditating mode is stop narrating yourself to yourself.

Guernica: That’s another neural area that’s affected: the language center.

Aleksandar Hemon: You have to suspend thinking in narratives. The moment you are conscious of yourself the gap opens up. And in this gap, stories are generated. Pronek, and all these other people I’ve written, are striving for this oneness that they think other people have. They fail to even get close to oneness and get stories instead.

Guernica: What has been the most surprising thing about living as a writer?

Aleksandar Hemon: I don’t know if surprising is the word, but I learned a hard lesson in Bosnia about art and its ennobling aspect, or the absence thereof. But despite all that I know rationally, and everything that I can put into words, I can say that I have difficulty giving up the notion of the nobility of art. I make money doing this, and I want to make money, and I would like to have a lot of money, but I still believe that the only reason to write is that somehow it will make something or somebody better. I do believe—and I know I shouldn’t—that art transcends money and success and any of that. You can still do it if you’re not clinging to the notion of nobility. But I am, I’m clinging to it by my nails. I really can’t justify it intellectually. I’d argue against it rationally. Yet, if it wasn’t for that—what would this life be? What would this world be? What the fuck would we do? I’m fully aware that it’s something that cannot be accomplished by me or anyone, but it’s something to strive for, and fail at, daily.

To contact Guernica or Brad Fox, please write here.