The writer on his book Methland, why newspapers got the meth crisis wrong, and how the “middle of America” will pull itself out of a twenty-five year bust.

Between 1983 and 2005, U.S. newspapers called seventy separate American towns the “Meth Capital of the World.” Following a late 2004 report in the Oregonian detailing the flourishing domestic methamphetamine trade, the media seized on the drug and its prevalent use in rural areas. It was pronounced an “epidemic.” But like a tweaker’s high, interest burnt out quickly, and these same papers started questioning whether meth was really as dire as urban addictions to heroin or crack. The Oregonian received a nomination for the 2005 Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, but lost to a New York Times series on fatal accidents at railway crossings. Small-town America, and reports of the meth epidemic, disappeared.

Between 1983 and 2005, U.S. newspapers called seventy separate American towns the “Meth Capital of the World.” Following a late 2004 report in the Oregonian detailing the flourishing domestic methamphetamine trade, the media seized on the drug and its prevalent use in rural areas. It was pronounced an “epidemic.” But like a tweaker’s high, interest burnt out quickly, and these same papers started questioning whether meth was really as dire as urban addictions to heroin or crack. The Oregonian received a nomination for the 2005 Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, but lost to a New York Times series on fatal accidents at railway crossings. Small-town America, and reports of the meth epidemic, disappeared.

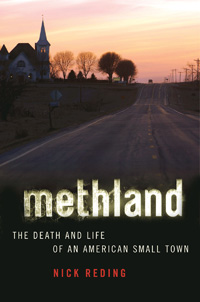

Nick Reding sought to change that. His Methland: The Death and Life of an American Small Town traces the four years he spent in Oelwein, Iowa, a town of 6,776 with one of the worst meth problems in the state. As before, the media is agape. “The madness stalking tiny, defenseless Oelwein may eventually come for all of us,” the New York Times Book Review declared in an article this summer. “Reding’s unflinching look at a drug’s rampage through the heartland stands out in an increasingly crowded field, ” Publishers Weekly belched.

But reactions like this reverse Reding’s priorities, putting the meth problem first and the town second. Reding first learned of Oelwein (pronounced OL-wine) through an article in the Des Moines Register where a doctor from the town called meth “a sociocultural cancer.” “That’s a smart thing to have said about meth,” Reding thought. He made a few calls and got the doctor on the phone on a Saturday. That Wednesday, he was driving north from Cedar Rapids to Oelwein. Over the course of Reding’s time there, the doctor, Clay Hallberg, became one of the principal characters in Methland, giving Reding a window into struggles to combat the town’s widespread meth addiction even as Hallberg struggled with his own alcoholism.

Reding describes the process of slowly gaining access to his characters’ private lives as a winding trail of phone calls and meetings. Often, the right person was just the one willing to talk most—someone like “Roland Jarvis” (lawyers requested his real name not be used). Jarvis is a meth addict whose rickety lab blew up his parents’ house, melted off most of his face and skin, and burned off his fingers and nose. “I’d be a liar to tell you when I first met Roland,” says Reding, “that I didn’t think that from a journalistic standpoint it was a home run.”

Reding describes the process of slowly gaining access to his characters’ private lives as a winding trail of phone calls and meetings. Often, the right person was just the one willing to talk most—someone like “Roland Jarvis” (lawyers requested his real name not be used). Jarvis is a meth addict whose rickety lab blew up his parents’ house, melted off most of his face and skin, and burned off his fingers and nose. “I’d be a liar to tell you when I first met Roland,” says Reding, “that I didn’t think that from a journalistic standpoint it was a home run.”

As a native Missourian, Reding doesn’t hide his love for the heartland and its people. The Colbert Report had cancelled an interview a few days before we spoke, but he didn’t seem to care. “It’s sixty-two degrees here during the day, the leaves are changing, bow season opened up a week ago, and I would much rather be here to hunt and hang out with my son and my wife.”

—Kyle McAuley for Guernica

Guernica: In the book, you talk about Oelwein as just any other American small town. How did you choose Oelwein? It couldn’t have escaped your notice that Iowa is where politicking starts.

Nick Reding: The only assumptions I made regarding Iowa’s place as a supposed bellwether was that people might give whatever I found there more credence—which, of course, I wanted. [But] I read a quote by Clay Hallberg one day describing meth as “a sociocultural cancer,” and thought, “Oh, that’s a smart thing to have said about meth. I wonder if he’ll pick up his phone.” That’s how I found Oelwein.

Guernica: What do politicians stand to gain in places like Oelwein that you or the media at large doesn’t?

Nick Reding: By definition, anything that’s covered over and over is no longer news; it’s old news. By contrast, doing right by the little guy out there in Oelwein is a favor that always sells in politics.

Guernica: Your book reads like you have a lot of sympathy for Oelwein.

Nick Reding: Writing is an exercise in manipulation—not in the negative sense, but clearly you have to define what you think, and then convince other people to see things the same way.

My friends’ reaction was fucking offensive. It was basically like, “What do you care about a bunch of trash making drugs in Iowa?”

Guernica: How, then, did you find your way into these people’s living rooms, into their private lives?

Nick Reding: A classic case is Roland Jarvis. I mean, he has fucked up in a lot of ways. He has done some really bad things. But at the end of the day, he’s a pretty good guy. He’s an easy guy to spend a few hours with. He’s a smart guy, got a good sense of humor.

Guernica: How did your colleagues react to the idea of you writing about meth in Iowa and Idaho?

Nick Reding: There were basically two reactions. One was, “Why would you want to go to Gooding, Idaho, again?” They’re my friends, so I don’t think about them as being jerks, but I’m a little bit loath to say what they said because it was fucking offensive. “Why do you care about a bunch of trash making drugs in Iowa?” The other reaction was, “Wow, I bet you’re gonna see some fucked up things.”

Guernica: There came a point in 2005 or 2006 where there was a suspicion that the meth epidemic was overblown.

Nick Reding: I think I probably clicked my heels a little bit when I heard people say that the whole thing had been overblown. To me, I had plenty of proof that was bullshit.

Guernica: Is it fair to say that you believe that the media tends to neglect small towns? In reviews, you’ve been called an “alarmist.”

Nick Reding: It’s not like meth is the fault of NBC and ABC and Reuters. I think they certainly could have dug deeper, but by not doing so, they sure allowed me a great little vein to mine. The meth epidemic had been oversimplified into one thing, which was, “Isn’t it crazy that people can make a drug in their sink?” I think the reaction was less to meth and Middle America than it was to the uni-dimensional nature of the coverage. And when people started to say, “Okay, where’s the evidence for this?” they discovered that the evidence was deeply flawed. One of the only sources of evidence about a drug epidemic comes from “studies,” which are themselves scientifically and logically flawed. So of course it looks like hocus pocus. Very few reporters are actually spending four years in Oelwein, Iowa. That is the privilege of writing a book. It’s certainly not the money. If you can get yourself in that position, you can get a good long while to look at something.

I thought, “Okay man, if everything goes right this guy is basically going to let me into his life. Then what am I going to do? Is it okay that I’m going to this man’s house in hopes that he’ll open up to me and that someday he’ll be reading about himself?”

Guernica: I’m reminded of how there was doubt in the eighties that AIDS was real or that it affected people other than gay men until more studies were done and media coverage intensified. Meth, though, is not in your bloodstream forever. Will we come to a point where there isn’t any doubt that it’s a public health problem?

Nick Reding: I think it is considered a public health problem, but there are caveats, some of which still exist with regard to AIDS. On some level, AIDS is still considered to be the disease of the “other.” Take black urban males and Hispanic rural males. There’s a correlation between those two demographics and rising AIDS infection. And yet it’s easy to say, “But I’m not a Hispanic rural male.” It’s the same with meth. At the same time we are able to say, “This is a public health problem.” We’re able to think, “This is a public health problem for a bunch of fucking tweakers.”

Guernica: As a writer interviewing tweakers, you’re essentially doing the opposite of making them “other.”

Nick Reding: I remember calling Roland from my motel room. I’d finally got him on the phone, and he said, “If you want to talk to me, you better come over.” I pretty much wanted to throw up the whole time I was driving to his house. I wasn’t looking forward to it. I didn’t want to meet him, man. I didn’t want to go in his house. I don’t know why. I wasn’t scared of him. I didn’t think less of him. I think that’s a reaction people have to new situations no matter what you expect. I thought, “Okay, man, if everything goes right, this guy is basically going to let me into his life. Then what am I going to do? Is it okay that I’m going to this man’s house in hopes that he’ll open up to me and that someday he, and a lot of other people, will be reading about himself?”

Guernica: But that’s your vocation.

Nick Reding: You’re not there because everything is going so great in Roland Jarvis’s life. Whether or not we got along with each other, I was still writing down everything he said. The intimacy of it is a little sickening.

Guernica: I listened to a public radio panel where you were on with an addiction counselor and the Deputy Director of San Diego’s Health and Human Services Agency. People would call in and talk about their or their friends’ experiences with meth addiction.

Nick Reding: In a lot of these radio interviews, people treat me as though I’m an addiction counselor. I’ve thought on a few occasions, “This feels a little irresponsible when people say, my son is on Ritalin, does that mean he’ll be addicted to meth?” My wife always says, “How come nobody asks you about your book?” (Laughs)

Guernica: Your book begins and ends with scenes of airplane travel. In the second, you’re flying from San Jose to JFK, and three hours into your flight, you’re trying to pluck Oelwein out of the cluster of lights dotting the heartland. Did your work on this book have a similar trajectory? Did working on Methland make a lot of the impersonal aspects of the meth epidemic personal for you?

You’re not there because everything is going so great in Roland Jarvis’s life. Whether or not we got along with each other, I was still writing down everything he said. The intimacy of it is a little sickening.

Nick Reding: Yeah, beginning most profoundly with a night in Greenville, Illinois, where I decided I would try to sell this book again. It was one of the few really clear moments with this book—and, honestly, in my life, period. I met these two guys [one of whom was an aspiring meth dealer], and that was it. I felt like I knew all of a sudden the context into which they fit. Doing the reporting for the book reacquainted me with a place that I had left half a lifetime before. I left home when I was eighteen and came back when I was thirty-six. I was looking for the place that my home occupies in the world—and what space do I occupy? Why is it that I’m yearning for this again? That flight from San Jose to JFK in August of 2005 was like the bar in Greenville, one of those defining, clear moments. I have some real misgivings about having my personal whatever in the book. But when I was writing it, there was this melding of my own path with the story. You spend four years with these people, and it becomes complicated. Are they characters in the book, or are they your friends? It makes me a little queasy to see how much of me there is in this book, but that’s just how it came out. It felt right to me.

Guernica: So what happens to the place you’re from? What happens to small towns?

Nick Reding: I don’t know what happens. That’s what this next book is going to be about.

Guernica: How are you framing this next book?

Nick Reding: That’s what I’ll be trying to do for the rest of the day and probably for the rest of the month—frame it in a true and logical and saleable way. One of the fascinating things to me is that a town like Oelwein is doing pretty well. They have completely succeeded in getting all of their small-time lab production out of town. Where has it gone? It’s gone to the next town about eleven miles away. Around here, you can have a town that’s doing fine and a town ten miles away that will probably not have any people left in it in twenty years. This is a bust cycle, and it is not to be viewed as the end of the middle of the country, but I think it is to be viewed as one of a long series of cataclysmic changes. So the question is, “Where do we go from here?” My guess is that the ones that are going to make it will do so through fairly intense localized diversification. Will that mean that some of them become railroad towns again? I don’t really know what the answer is, but I know what the questions are.

To contact Guernica or Nick Reding, please write here.

Photo by Taka Yanagimoto.