Estimated at less than 50,000, the Kayan tribe of Burma’s northeast have long been the essence of exotica, subject of curiosity, and source of “Ripley’s Believe it Or Not” obsessions. Because of some of the women’s traditional adornment of coiled metal rings, which enhance–or perhaps disfigure–their necks, the Kayans are also known by the name the lowland Burmese gave them: “Padaung,” meaning “long necks.” Years ago, National Geographic magazine x-rayed some Kayan women and determined that their necks had not been stretched, as it appeared. Actually, the women’s collarbones had been pushed down to create the long-necked effect.

Before that scientific exercise, in the days when Burma was a British colony, the intrepid artists, photographers, and ethnographers of the Empire gave the Kayan women plenty of attention. In Burma and Beyond, Sir George Scott, imperial adventurer and football hero, wrote of the “Stiff-Necked Belles”: “It is the get-up of the women that makes the Padaung the best-known of the tribes. In fact this has led lately to their being brought down to Durbars for viceroys and distinguished visitors to look at.” He also noted, “Some of the girls are by no means bad-looking, but their formidable armour not unnaturally seems to deter suitors other than the men of their own race.”

bq. At that time, those Kayan captives were often loaned to officials from Thailand, to be taken across the border and displayed at carnivals, county fairs, and “beauty contests”

A few of the Kayan “belles” were exported to England for show. Kayan writer Pascal Khoo Thwe’s grandmothers were among a group which made the long journey, “to be taken around Europe by a circus called Bertram Mills and exhibited as freaks.” They returned home with English money, photographs of their travels, and accounts of strange sights and customs (moving staircases, tea-time, uncomfortable shoes).

One explanation for the neck-rings is that they were intended to make the women of the Kayan tribe distinctive, so they might be ransomed back from captivity in times of inter-tribal warfare. Some claim that the practice was meant to protect women from tigers, which are known to seize their prey by the scruff of the neck. In any case, the custom grew to have strong implications of power rather than helplessness, and the rings were an aspect of one of the modern world’s few matriarchal cultures. While the neck-rings and similar coils on arms and legs hampered mobility, the men of the Kayan tribe did help out with childcare and everyday drudgery, and value the opinions of those who wore the weight of metal. Khoo Thwe writes in his memoir From the Land of Green Ghosts:

“The rings are of one long coil made from an alloy of silver, brass, and gold. Only girls born on auspicious days of the week and while the moon is waxing are entitled to wear them. These girls start wearing rings from the age of five, when the neck is circled only a few times. As they get older more rings are added.” And added, and added, eventually forming a shining tower of polished metal. Khoo Thwe feels that the rings are meant to connect the women who wear them to “the memory of our Dragon Mother.” The Kayans believe themselves descended from a female dragon who mated with a male human/angel hybrid. “Our grandmothers would allow us to touch their ‘armour’ when we were ill,” Khoo Thwe writes, “One should touch them only to draw on their magic–to cure illness, to bless a journey. The rings were portable family shrines. This was a practice older than Buddhism, but which was absorbed into the later religion [and tolerated by Catholicism, which eventually converted the Kayans]. The women also tucked money into the rings. For us children they were like walking Christmas trees, full of family treasures and miraculous powers.”

My own Kayan/Padaung obsessions began when I encountered neck-ringed women while I was visiting insurgent camps along the Burma side of the Thailand/Burma border as a human rights researcher in 1985. The Karenni ethnic rebels, longtime fighters against Burma’s brutal military dictatorship, played host to a small band of their Kayan relatives. The Karennis allowed tourists and journalists to go by riverboat from their camp to a walled compound wherein dwelled the Kayans. As I put it in my book Burmese Looking Glass: “Sensing their potential as tourist attractions, a sinister Padaung man had recently brought three of the women to the Pai River to draw in boatloads of day-trippers.” The women were not there voluntarily and that man turned out to be a spy for the Burmese Army–which later over-ran the Karenni camp. “This is the story of Helen of Troy,” I had thought, John Cale’s dirge in mind.

bq. “Their necks weren’t that long,” complained some tourists, who apparently expected something out of science fiction.

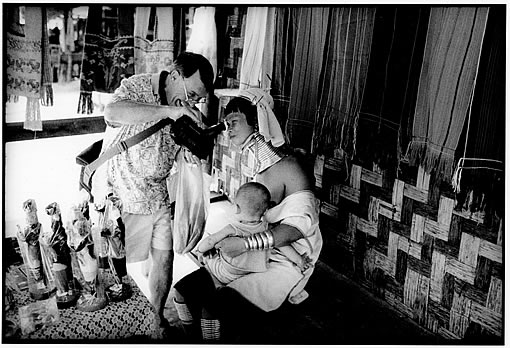

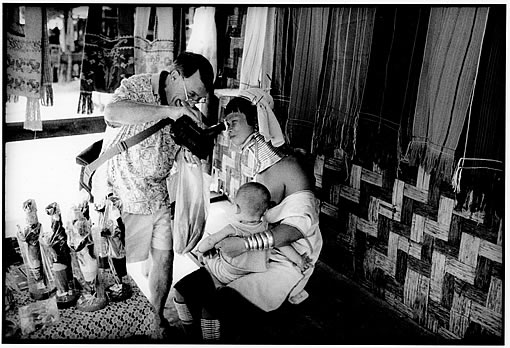

I went to visit the Kayan compound without a camera but with a sketchbook. I wrote of my visit, “The two younger women, in their late twenties, were at home. Both had round faces turned up by their brass neck coils, wide mouths, bangs fringing their eyebrows. Their hair was piled up in bright towel turbans held with silvery pins. They posed, expecting the foreigners to photograph them. They also posed because they couldn’t help it. Their movements were so restricted and stylized by gleaming brass–not only the neck spirals, but coils immobilizing their knees as well–that they carried themselves like languid, elegant fashion models.” At that time, those Kayan captives were often loaned to officials from Thailand, to be taken across the border and displayed at carnivals, county fairs, and “beauty contests” (a euphemism for the auction of hill tribe girls to Thai men.) Often ill and frightened, the Kayans nonetheless endured these humiliating events with a certain stoic dignity.

After the Karenni rebel camp was taken by the Burmese military, its inhabitants became refugees on the Thai side of the border. The exploitation of the Kayan women continued in a refugee settlement signposted in English as “Long Neck Village”. A nearby hotel, The Mae Hong Son Resort, advertised “Padawn Hilltribe now available. On special arrangement in advance.” This added a new freak show element to the “human zoo” syndrome in Thailand, which sent parties of foreign trekkers off to “remote” hill villages to gawk at increasingly objectified and commodified tribal people (embroidered clothing, bamboo huts, opium poppies) with the “primitive” as a surefire advertising pitch.

“Their necks weren’t that long,” complained some tourists, who apparently expected something out of science fiction. The Kayan women were told to sing in their quavery down-a-pipe voices when the gawkers got bored with their quiet posing. To liven things up, they sometimes posed with the M-16 rifles of Karenni insurgents. A very far-fetched Belgian comic book, Les Femmes Giraffes, was obviously based on such a snapshot: in its pages some French-speaking assault-rifle-wielding Kayan girls brave Komodo dragons to liberate prisoners from a “bandit” diamond mine. At one refugee village, a board painted with Kayan likenesses, minus faces, was set up so that tourists could poke their own heads through for a comic photo-op. Thai tour agencies displayed posters and postcards advertising the Padaungs (Kayans) as “one of the hill tribes of Thailand.” I plastered stickers–“this exploits refugees”–on the travel agency posters of the women, and in Hong Kong I wrote letters to the editors protesting “long-neck” tourism articles: “This woman is not a ‘human giraffe’ as the headline so demeaningly puts it, she is a war refugee.” Hostages to tourism, I called them.

The ongoing Thai freak show actually proved something of a blessing for the Kayans as they were allowed to stay on in border camps even when less marketable refugees were forced back into the war zone by the Thai border police. Thailand’s Nation newspaper reported this in 1989: “families whose female members have become a tourist attraction because of their artificially extended necks, will be exempt from the planned repatriation. They may be given temporary border passes and allowed to stay for promoting tourism.”

Throughout the 1990s and into the new century, refugee camp existence in Thailand dragged on for many Kayans. Things were unrelentingly horrible in Burma, and a 1995 report warned of Kayan women being sent to the capital, Rangoon, for exhibition in a “human zoo” as part of the Burmese regime’s international promotion of tourism effort. Another “human zoo” situation, set up with 32 neck-ringed women, was described by Associated Press reporter Denis Gray, in Thaton, Thailand (far from the border) in 1998: “Before a recent police raid, there had been charges the exotic tribespeople on show were being held virtual prisoners by a Thai entrepreneur who allegedly abducted them from neighboring Burma.”

According to Gray, displays of Kayan women were attracting some 10,000 visitors a year to refugee camp tourist traps along the Thai/Burma border. He wrote: “the long-necked women have become Mae Hong Son [Thailand] province’s unofficial symbol, a come-on for tourists to a region where many other tribal groups now wear jeans and ride motorcycles. In Mae Hong Son, officials, guides and others like to call the Padaung ‘our long-necks’…” Eventually very young Kayan girls started getting neck-rings as a way to stay in Thailand and make money. The custom, never widespread to start with, had been on the wane, and now it was being revived for all the wrong reasons.

Some people thought the neck-rings should be entirely a thing of the past, should go the way of footbinding, but the Kayan rings–neck, arms, legs–were not nearly as debilitating as the old Chinese practice of the crippling “lotus foot”. They were more comparable to the life in spike heels led by many a modern woman, and certainly less invasive than a nose-job or breast implants. To me, the rings are less the stuff of freak shows than of fashion shows, a most graceful device. They have seemed a bit akin to the “tribal” body modifications revived in the developed world in the 1990s, those dark unconcealed tattoos, the mutiple and weighty piercings. Yet the Kayan rings were a form of belonging and tradition instead of a form of rebellion or fad.

These days we see many a fair-skinned person with Tlingit lip-plate, extended Borneo earlobes, or boar’s tusk through the septum. My own Irish-Italian elbows have magic tattoos drummed into them by a Shan wizard on the Thai/Burma border, and I have been known to weigh down my forearms with silver bangles. But I have yet to hear of a non-Kayan woman (or man) actually pushing down their collarbones with a great coil of brass tubing. The Kayan women have some sisters in the Ndebele tribe of South Africa, who would don metal neckrings at marriage, the number an indication of social status and wealth. The throat would be covered, but not to the stretching/pushing degree of the Kayan rings and the use of permanent rings seems to have died out among Ndebele women. So sui generis the Kayan rings will remain, unless other particularly desperate refugees from Burma adopt them for a free pass to Thailand’s awfully dubious haven.

Despite its marginalization, the Kayan women’s extremist aesthetic has a certain reach. A much-published advertisement for Dior’s J’Adore perfume shows a blond model in a necklace of thin gold rings that cover her throat from chin to shoulder. The scent’s bottle features golden coils around its glass neck, as does that of the British cologne called Monsoon. “Extreme Beauty”, a 2001-2002 exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, featured images of Padaung and Ndebele women, stars of the section devoted to “the neck and shoulders”. In his catalog text, curator Harold Koda comments that “the preference for a long neck is perhaps the only corporeal aesthetic that is universally shared… in all cultures, the head held high is associated with dignity, authority and well-being.” Koda writes of England’s Queen Alexandra inspiring an early 20th Century vogue for high collars and stacks of necklaces as she covered up a scar on her neck. In an unremarked-upon juxtaposition, the book’s full-page photo of a Kayan woman clearly shows her neck-ring and hairband decorated with silver Raj rupees minted with the likeness of Alexandra’s husband, King Edward VII.

bq. [The rings] were more comparable to the life in spike heels led by many a modern woman, and certainly less invasive than a nose-job or breast implants.

Koda’s “Extreme Fashion” catalog includes a couple of 1997 high fashion runway shots in which Dior designer John Galliano’s models wear dramatic chin to shoulder necklaces. A photo from Alexander McQueen’s fall ’97 collection shows a high neck-ring, very authentic-looking except that it seems a bit loose (the model’s chin sinks into it, instead of jutting out above it). The same designer put Bjork in neck-rings (and kimono) on a CD cover he designed for her. McQueen also commissioned a complete wire-coil “carapace”, as Koda calls it, a low-waisted silver turtleneck top with short sleeves, going a bit further than a graceful coiled wire bustier created by Issey Miyake in 1983. This use of wire beyond the normal realm of jewelry must have been inspired by pictures of the Kayan and/or Ndebele women, and follows the always-pleasing forms of coils and springs, spirals, and Slinky toys.

The image of the naturally long female neck, a lovely fetish, means elegance, in a timeless, placeless way, from sculpted Nefertiti to the block-print geishas, Audrey Hepburn in her decollete Givenchy to Burma’s own Nobel Laureate Aung San Suu Kyi. Perhaps it is all a matter of being calmly assertive in demeanor, literally sticking one’s neck out. Aung San Suu Kyi and the Kayan matriarchs certainly do. There is a pervasive fear of women’s intrinsic power in Burmese culture, and a concerted effort by the military regime to demean women, especially evident in the mass-scale military rape of ethnic minorities. At the same time, the defiance of women is pivotal to the resistance movement in Burma. The Kayan women in their metal coils can be presented as freaks, animals, and amusements–but they remain an outright manifestation of defiant power, witchery, and autonomy. They are a vision of steely determination, armored and aloof.

The coils of polished metal around the throats of the Kayan women give emphasis to their rounded wide-cheekboned faces, framed by a dark fringe of hair and a profusion of color in earrings, ribbons, and ornamented topknots. A strong chin and jawline become prominent in a way that is otherwise pretty rare in women. I think that the copper angels are meant to be respected by other Kayans, admired by the rest of humanity, and shunned by tigers.

Edith Mirante is the author of Down the Rat Hole: Adventures Underground on Burma’s Frontiers (Orchid Press, 2005). She runs Project Maje, which distributes information about Burma’s human rights and environmental issues (projectmaje.org).

Nic Dunlop is a Bangkok-based freelance photographer represented by Panos Pictures in London. He is co-author of a book on landmines in Cambodia entitled, War of the Mines, published in London in 1994. Nic’s latest book, The Lost Executioner was published by Bloomsbury in May 2005 and released by Walkerbooks in the US in 2006. He is currently working on a photographic book on Burma’s dictatorship. View more of Nic’s work at www.panos.co.uk.

To comment on this piece: editors@guernicamag.com