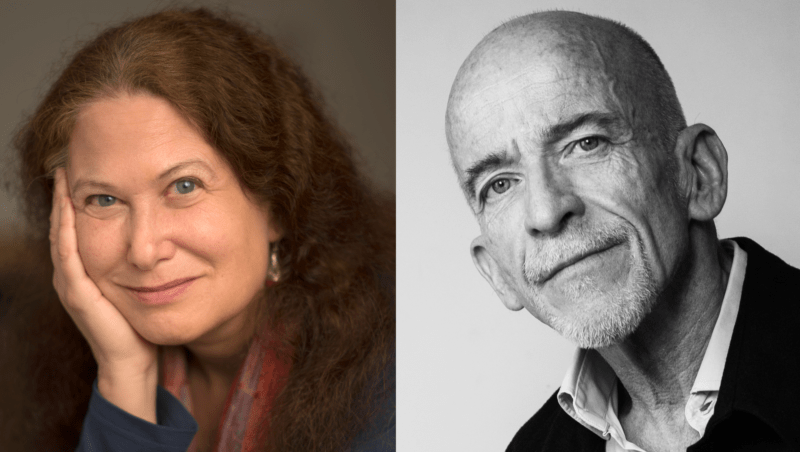

In late February, 2020, friends Mark Doty and Jane Hirshfield, both poets with new books then on the verge of publication—Doty’s What is the Grass: Walt Whitman in My Life, and Hirshfield’s Ledger: Poems—began exchanging emails exploring each other’s work and the relevance of poetry in today’s chaotic and frightening times. As their exchange unfolded over the early spring, they found themselves increasingly entangled with the question of how a person can write not only into the longer-standing crises of climate, social fabric, and justice, but into the arrival of the global pandemic—which informed their missives to each other, as it did their lives.

Dear Mark,

When I think of your life and your poems, even the proscenium part—the public words of the published pages, set in front of the curtain of the personal life—seems so vast it’s impossible to sum. Names and nouns, persons and places, race through my mind: Wally, Beau, pipistrelle, Jackson Pollock, Broadway, Atlantis. Still, the word that arises for me, just now, as a central, abiding quality is “iridescence.” According to my Merriam-Webster: “a lustrous rainbowlike play of color caused by differential refraction of light waves (as from an oil slick, soap bubble, or fish scales) that tends to change as the angle of view changes.”

Even in those dictionary examples, it seems that iridescence—a beauty born of perspective, of layers, and of the angle of relationship between seer and seen—travels in the company of visible suffering. An oil slick is both beautiful and a substance profoundly out of place: even the few drops of gasoline rainbowing a puddle are an insult to the earth’s well-being; whoever drinks that water will sicken. A soap bubble? The very definition of transience. Fish scales— marine-biology iridescence seems always to arrive as layers answering friction. And then also, what of the fish? I read “fish scales” and think of the ones in Elizabeth Bishop’s “At the Fishhouses”:

The big fish tubs are completely lined

with layers of beautiful herring scales

and the wheelbarrows are similarly plastered

with creamy iridescent coats of mail,

with small iridescent flies crawling on them.

[…]

The old man accepts a Lucky Strike.

He was a friend of my grandfather.

We talk of the decline in the population

and of codfish and herring

while he waits for a herring boat to come in.

There are sequins on his vest and on his thumb.

He has scraped the scales, the principal beauty,

from unnumbered fish with that black old knife,

the blade of which is almost worn away.

I’ll digress to say that I’ve always been surprised that those who write of your work and its lineage never seem to mention Bishop. Do they think a male poet doesn’t read the poems of women? You can of course correct me, if you think I’m wrong in finding so much resonance between her work and yours, but either way, Bishop was also a poet of rainbow, of gleam found companion to suffering. There’s not only the famous rainbow at the end of “The Fish,” but others, including the one in her last-started finished poem, the posthumously published “Sonnet”:

[…]

Freed—the broken

thermometer’s mercury

running away;

and the rainbow-bird

from the narrow bevel

of the empty mirror,

flying wherever

it feels like, gay!

Mercury’s gleam released by having been broken; the mirror empty, its observer absent…This poem’s entered freedom is a wing-spreading joy. And still, a person might be forgiven for wondering if gleam is ever present in poems except as the mark of suffering transposed into larger beauty, found at a cost. You don’t find release without first having felt yourself bound.

I find this specific, always astounding, transmutation running throughout your own work. From the earliest to the most recent, your poems take loss, illness, grief, a dead green crab, and find in them, well, Handel’s “Messiah,” sung by a community chorus that welcomes the singers as the frail, flawed beings they are, and also transforms them, and then transforms us, who read that poem, into beings able to awaken—and awaken into—transcendence.

You’ve written about HIV-AIDS, about the loss of beloved dogs and beloved humans, about the death of Tamir Rice, in poems that are shattering, and shatteringly beautiful. Can you say something, anything, about the reason for—the ways that—nacre comes into narrative? And about how that works in your poems and psyche now, in this moment’s conditions and currents? I know that What Is the Grass, your recently published book on Whitman, was written over many years. Has he been a model, a solace?

Love,

Jane

Dear Jane,

That was such a graceful (and gracious) disquisition about my work, thank you. Bishop’s work, in particular the great descriptive narratives like “The Fish” and “The Moose” that reach through their scrupulous evocations of perception toward making a claim on meaning—well, those are among the poems I love best, ones I’m never finished reading. In part that’s because the speaker we meet there is so engagingly faithful to her own idiosyncratic, pleasurable attention to things, and in part because the larger claims she makes remain open. The little boat fills up with victory, but whose? And over what? If its outward sign is oily rainbow, that may well not be visible to the fish, and likely could kill him. Is it the speaker’s victory, for having “caught” the fish in language, and so able to release it? Or in fact a sort of “victory” in acknowledging that the world can’t be circumscribed by language, and thus the victory really does belong to the fish? Or to no one, but to the joy of inhabiting a world that is always more than we grasp?

Bishop wouldn’t like this assertion, but I think the clear antecedent of “The Fish” is Walt Whitman, who says to everything around him “you furnish your part toward the soul.” Thus he can look at a field of grass, in “Song of Myself,” and generate an associative list of terms for it, making a litany out of these figures: the flag of my disposition, the handkerchief of the Lord, a uniform hieroglyphic, and finally the one-line stanza he throws like a sort of spiritual grenade into American poetry: And now it seems to me the beautiful uncut hair of graves. Everything seems to stop when he says that. The other descriptive figures aren’t erased, but they recede, and the remainder of that section of the poem doesn’t mention them again. So why keep them in? Like the marvelously diverse details in Bishop’s poem, they replicate a process of perception; they invite us to feel the speaker is thinking the matter through, working toward meaning as the poem is being spoken.

And that makes me think of a phrase of yours. At one of the—how many?—gatherings where you and I have talked about poetry together, you said that lyric poetry is “a technology of shift.” I love that idea, that a poem’s a means of reinterpretation, allowing us to see a little differently by … refocusing the lens, turning the prism? Perhaps the more intractable the thing we look at, and the less control we have over that reality, the more attention we have to give to the lens.

How do you shift as stark a fact as our mortality, our position in time? Or the world’s continual offerings of misery to those who live outside of huge, grasping economies—and, in different and less immediate ways, to the privileged too?

The “nacre”—the sense of illumination, a shine that elevates, attempting to point toward a reality that might be larger than individual loss—is easier to get to with some distance. In a poem called “A Display of Mackerel” I suggested that the fish were shimmeringly beautiful because they don’t have selves; their life resides in the flashing school, the leaping vitality of their kind. That may be true of us, too, but who can say that? If you love anyone, even your dog, you understand that creature is a specific individual who is doomed to be lost. It would be dishonest to represent such beauty without this shadow—but equally false to portray our suffering and limitation without recognition of the splendor of simply being here.

It’s a provocative question for me, how a poet who thinks of poetry as in some way a redemptive act, an attempt to shift the way the writer sees and thus enable a shift for the reader: How does that poet address what seems unredeemable? I haven’t been able to coax climate change and its vast potential for destruction into a poem of mine, except for the briefest mention in a poem or two. Are there things that have seemed to you un-writeable, where you saw no possibility of shift? And have you then found ways, some of the time, to hold them up into the light?

Love,

Mark

Dear Mark,

We’ve come so quickly right to the heart of it here, the particular, individual, beloved, mortal existence and then the large, shining-with-galaxies existence each singular, irreplaceable, passing being is part of. Are we one, many, one-among-many, many-that-knows-itself-one-by-one? Whitman’s question with which you’ve titled your book—“What is the grass?”—goes straight to it. Is a single blade of grass even “grass”? (It goes to many other things as well, of course, beyond this aspect of grass-ness.) I’m going to forego further response to that part of your thoughts, though, and answer your more specific question.

In some way, every poem I’ve written has felt entirely un-writeable, until it’s been written. Until words come, there’s only abyss and precipice, an insurmountable cliff-face. As a writer, I feel like Psyche in the Greek myth, a person given tasks she cannot possibly accomplish, until other, beyond-human beings assist her. In the myth, ants sort the grain. The sheep’s wool has been already gathered, by brambles. An eagle, a reed, a tower give aid. Words, for me, offer similar forms of assistance. They bring to my stunned bafflement, grief, and fractures of understanding lives of their own, capacities of their own, their own saving energies and knowledge. When shift is needed, they open the locks—of doors, of canals, of spirit, of tongue, of heart. At times when the outside world’s facts—or the heart’s facts—seem immovable, words still can move. And from that re-finding of motion and agency, new possibilities spring.

You spoke a little about poetry’s openness, the way its images can offer multiple interpretations at once. This shimmer of pure possibility, I think, is one of the reasons poems are so needed, and one clue to what good poems offer—offer us individually, and as a collective, as a species traveling together through millennia, across cultures, languages, oceans. Poems are like lives: they don’t face only one direction at once. Poems don’t treat our existence or dilemmas as a mechanical problem with only one correct answer. Iridescence is beautiful not least because it isn’t single; it can’t be taken fully in, domesticated, or even captured. It doesn’t exist in itself; it has to be seen—which requires both a person, a seer, and as you say, a certain distance. Iridescence holds many possibilities at once. We can’t name its color, which continually shifts. All this is also what the vision of poems is engaged in: in the face of communal or private crisis, we need and want to see more than can be already seen. As the old cowboy insult has it, we’re trying to put ten pounds of rice in a five-pound sack. But unlike that saying’s original intention, in poems this impossible thing can be done. And if it isn’t, if the words aren’t in some way surpassing their own conceivable reach, those words aren’t yet a poem—or at least, not a good poem, or a poem worth re-reading. To conceive the inconceivable is poetry’s task.

And so, we (or those of us willing to do it) look at the cliff-face of what seems impossible to live through—the willful self-destruction of this moment’s version of earthly existence. For me, I can take outward action—and do, every day. I send postcards and letters, make phone calls, put comments on government public-comment web pages, donate to those doing work I can’t do myself. I turn down the heat and do cold-water laundry.

But then sometimes—as Czesław Miłosz advises, rarely—I write a poem. I don’t know how we will move the tiller of the culture except by the increase, first, of awareness. Of our willingness to see and recognize the full brunt of what we are doing when we pursue our private lives without remembering that those lives are shared with all others, on a planet on which we now know our discarded plastic will enter the bloodstreams of birds and fish, will entangle even those largest mysterious beings, blue whales, in what we have made of, done with, the earth’s abundance and our own ingenuity…

Many of the poems in Ledger have been magnetized into being by the sense of absolute urgency I feel in the face of the biosphere’s ruining. Others, by the violence we humans bring against one another. I was in Syria in 2007, before the civil war started, when Syria was the country taking in 750,000 refugees from the war in Iraq. Now, many, most, of the university students I met must be refugees themselves, or dead. I’m haunted by their voices and faces. In those meetings, I would ask, any chance I could, “What would you like me to tell people for you, when I go home?” And they would say, “Tell them we are students, not terrorists. Tell them we are just like you, we want to do good work, we want to fall in love and marry, we want to have children.”

Thinking of those young people and their lives, who would want to write a poem that seemed writeable?

To say the known is not what poems exist to do. Neither is silence a response that we—I—can live with. And so, after seeing a drone-video of the destroyed Syrian city Homs, I saw some pelicans in flight, saw their black-tipped wings, and then wrote of that city, that video, and of my own sense that no language, no thought, no beauty, can answer such unthinkable, unimaginable undoing of lives.

Perhaps Ledger’s poems amount to a kind of stuttering—we witness this earth in all its beauty and all its suffering and cannot make the sum come out, and so we say with our poems: “but…but…but….” And even that stuttering, inadequate to reality, is at least a responding, a protest, a molecule’s insistence and testimony that life is alive to life. Is that “redemption”? The poem “Homs” says, explicitly, no. But it is at least not silence. Not indifference.

I think your work is also an insistence on witness. The great poets—Whitman, Dickinson, Cavafy, Homer, Dante—expand the vocabulary of witness. They are telescope, microscope, bubble chamber, MRI machine, SETI array. They gather not only data, but new ways of seeing, of knowing.

I’ve always disliked Harold Bloom’s premise that Shakespeare somehow “invented the human.” What hubris—as if Homer, Murasaki Shikibu, Euripides, Sophocles, were somehow lacking. But great poets do add to the lexicon of the human. They face into their own time, whose needs and vocabulary will always be new and different, requiring their own tongues and eyes to tell its lives and stories.

The world’s earlier writers are indispensable to navigating current crises. The world’s current writers are indispensable to navigating current crises. Any poet who can offer a phrase—pocketable, encouraging, accompanying, meaningful, useful—enlarges existence. Whitman offered a worldview of embrace and connection, inner, outer, between us. At his best—and let us grant right off that poets in their lives and days will always be lesser beings than they are in their poems—he is the poet of absolute, radical equality: between beings, between even life and death. He takes the side of it all. And that written, transmitted understanding of Whitman’s has become part of what has made you, and made me, the persons and writers we are. I don’t think Whitman could have known much about the Buddhist teaching of compassion. A little, perhaps—Emerson and Thoreau were reading translated sutras. Yet he embodies compassion and the awareness of shared fate in all his poems.

Embodiment. What might you say, with that as stepping stone? In your own work, as we face our too-many, simultaneous crises of justice-equality and biological precipice? In Whitman’s, as he faced the crises of his own time? In our culture’s attempt, all too often, to escape the body entirely?

Love,

Jane

Dear Jane,

You’ve articulated something essential here, and as usual, in an exact and useful way. Every poem is un-writeable until it’s written—or, let’s say, every good one is. We look at the insurmountable cliff-face of experience, something we feel compelled to name that troubles or puzzles us, something that seems to require our witness. We begin in bewilderment or despair, or soon arrive at them, because we feel we don’t have means commensurate to the task. We have words, the same language we use to order lunch or talk to a teller at the bank, but it seems to be our given work to use our medium to make poems that will point toward what we can never fully say.

Here’s Whitman, addressing his readers, in “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry”: What the study could not teach—what the preaching could not accomplish is accomplished is it not? After years of living with this poem, those lines still give me a little shiver. How does he know this, that his poem is a kind of transmission across time, an insight that can’t really put into words? But there’s nothing in a poem but words. Elsewhere he writes, There are buds folded beneath speech. He must mean that words can open in us, and thus say more than they seem to. Like Dickinson, he is possessed of a startling self-awareness. He understands that he has just said something—something I might roughly summarize by saying that the soul is not bound in space and time, and that he can continue to step outside his moment to us, wherever and whenever are, through the agency of his poetic voice—that the poem does not and cannot say. Nothing we make will ever be as layered and complex as reality is. A poem as charged with vision might, with labor, attention and luck, gesture in reality’s direction.

I think your suggestion that every poem confronts the same challenge—wrestling some of the wordless into language, and thus enlarging us, shifting the scale of what we’re able to think about—offers a key to writing poems of social and political engagement. Those poems have to be just as personal, as intellectually and emotionally charged as any other. There are two real challenges to achieving that. First, when we address a public issue, we tend to know what we think before the poem is even begun. I don’t have to figure out what I think about the brutal and obviously racist behavior of the police officer who pulled over Sandra Bland in Texas for failing to signal when she changed lanes to get out of his way. Second, I wasn’t there; I don’t have sensory information to use as a departure point for a poem. The language is already mediated, the stuff of news reports.

This is indicative of a larger problem. Many American poets—those of us who are middle class or well-to-do, white, or dwell in communities that insulate us from difference—can feel that politics is something that happens elsewhere, at a distance. One consequence of this is that we don’t always recognize bias when it comes close to home. It’s important for me to remember that it’s only a step from the cops harassing the queer pier kids who hang out at the end of Christopher Street to those same cops harassing me. I don’t enjoy the crazy noise those roving packs of teenagers, angry at the world they’ve landed in, make. But I’ve known anger and hurt because of my sexuality as well. My knowledge of that common ground makes my life in this city more real, and helps me stay awake to where I do and do not have privilege.

If I am going to scale that cliff and write a poem that speaks to the conditions of our common lives, I need to be as aware as I can be of the position from which I speak, of what I can and cannot know, and I need to find that cord of fellow-feeling, of the human held-in-common, that is essential to making my poem something besides a report, a spectacle or an op-ed. It was imperative to me to write a poem about the death of Tamir Rice, the twelve-year-old boy who was murdered by the police in Cleveland because he was playing with a toy gun. But how? I felt the horror of his having been erased—the arbitrary, immediate end of a chain of being passed down through history, everything that made him. And then, had he survived, all that he might have done, all that could have issued from him, had life not been interrupted. As I began to find imagery for that, groping around for words, I realized I didn’t need particulars of his life; had I used them, it would feel as if I were making a claim to know him. I couldn’t do that, just as I would not claim to know what he felt. I used the most generic of details, giving him a pocket knife and a lost cat’s collar, describing his mother folding his clothes, in order to show him as any boy whose life is cut short for reasons that have nothing to do with him.

I did make a discovery, during the process of writing that poem, which has to do with empathy and its limits. I have always thought that no character in a poem or memoir can be presented in a purely negative light. People cannot be reduced to caricature, and if you do so readers won’t believe you. (This might be one way that art actually is redemptive, since it invites its maker to find some means of understanding those who otherwise might merely be judged.) I understand that the officer in question might have been overworked, exhausted, overwhelmed, that he might have come from an intolerant background, that perhaps he made, for some unknowable reason, a mistake. But my poem required me to refuse empathy for him; his actions were part of an endless procession of acts that we as citizens can and must stop. The poem felt like a loud, somehow-collective no, one not spoken by me alone.

One last thing about this subject: Poems that address crucial issues often are criticized for “preaching to the converted.” How do you respond to that charge?

Love,

Mark

Dear Mark,

One response that comes up right away, pondering your thoughts, is the necessity for simple, basic humility—of both words and self—to counter the (possibly inevitable?) quotient of arrogance that comes with making any statement at all, let alone putting forward into the world a statement taking the form of a poem. We know nothing. We know nothing. We know nothing. A good poem won’t preach—not to the converted, not to the unconverted. And so, you say here, “My poem required me…” You say, “I could not claim to know what he felt.” So long as we know how much we don’t know, so long as we listen to what wants to come through us, so long as even the highly charged poems of collective voice and collective conscience know how much we don’t know, poetry will be not the ravings and bludgeoning of enforcement but an offered invitation to understand more than we might have been able to, had this very poem not existed.

Poems have ethics. We don’t pretend to be someone we are not, to have been somewhere we were not. Long ago, when I felt utterly helpless, torn open by the accounts I was reading of the genocide taking place in Rwanda, I wrote a poem. The first thing that poem had to do was admit, explicitly, that it was written from newspaper knowledge. Nor did it cast blame, or rail against some imagined “them.” Your “In Two Seconds,” I’m guessing, must have been terrifying to write, because it does hold that police officer to account, unstintingly, sharply. But in poetry, we both know, even what is said in the negative exists in the positive. That is how the art works. And that poem—easily found online, for readers who may not know it—raises into existence and awareness even the empathy it declines to offer.

The poem in Ledger that truly frightened me when I wrote it, and frightens me still, is “Ghazal for the End of Time.” More fully than any poem in the book, it imagines a complete failure to alter our human course, and what will then come: an atmospheric and biological balance so ruined that death itself would have no living home to inhabit. I know that won’t actually happen. There are resilient species and microbes that will survive the worst we can do, perhaps even our own. But this winter, in California’s usual wet season, we went almost six weeks with no rain at all. And the phrase from that poem, “Rains stopped,” was suddenly not something imagined at all. Just as a different line, “Fish vanished. Bees vanished. Bats whitened. Arctic ice opened,” describes things not imagined, but already real. These are past-tense, not future-tense, statements.

During the weeks we’ve been holding this emailed conversation, the coronavirus crisis that began in the city of Wuhan has become a global pandemic. We didn’t mention it earlier because it was only during the week of our just-past interchange that, here in the US, everything changed. One line from Ledger stepped forward for me between the second poetry reading I gave for the book, and the third, final, reading (“final” because all public gatherings were abruptly and rightly cancelled): “You go to sleep in one world and wake in another.” So it did feel, between the night of March 10 and the morning of March 11. And poems written pondering the crises of biosphere, of social justice, of refugees, suddenly began to speak into a crisis in retrospect recognizably inevitable, but which they could not have foreseen.

By the time this conversation is read, if it is read, it will be a different world again than the one today. Today—March 21, 2020—I am “sheltering in place,” in the San Francisco Bay Area, along with almost seven million others. By tomorrow, you in New York City may have joined us in this, or may not have. Today’s number of diagnosed cases and deaths will be irrelevant tomorrow, forgotten by next week. Whether this illness will join the 1918 Spanish flu in the story of our species can’t yet be known. But in this changed moment of the past few days, two of my poems—one from Ledger, one written a quarter-century earlier, both written for other reasons—have been read now by something like a million people. There’s no current medical treatment other than palliative support, no current vaccine, not even enough tests to be had. All that will someday change. Meanwhile, among the still-healthy, some people turn to a phone call, some to email, some to a video conversation, some to a poem. In “social distancing,” what brings us together is words.

Whitman brought both his life and his poems into the center of the Civil War. That immeasurable conflict is in the poems of Emily Dickinson also, just more obliquely. The worlds we find ourselves in can’t be escaped. We breathe the molecules of each other’s lives, and of factories around the earth. We breathe radiation released decades back. We speak suddenly of hand-washing. I ended the question-and-answer that followed my reading from Ledger at the Poetry Foundation in Chicago talking about hand-washing for the prescribed twenty seconds under running water, and how that collides, for me, with the awareness of fresh water’s coming scarcity in the climate-changed world. Surely the oddest thought with which I’ve ever ended a reading.

But longer standing crises don’t vanish because a newer one has arrived. And so, I sit here, wondering if it is possible we humans will emerge with a better understanding of our intimate co-existence with one another, our interdependence with all other beings. Wondering if the tenderness between people that’s now welling up will hold, or if it will fail. One of poetry’s tasks is to carry within it the knowledge that tenderness, vulnerability, the desire to feel and the desire to know our connections, are—under any circumstance—the only actual option, if we are to know the actualities of existence and the fullness of our own lives. In your “In Two Seconds,” there may be fierceness—but far, far more, there is tenderness. The poem takes the side of Tamir Rice, and of life. Poems, good poems, take always the side of life.

The seventeenth-century Japanese poet Bashō, when he was dying, wrote:

Deep autumn.

My neighbor,

how is he doing?

So, I now ask you, with Bashō as our supporting companion: How are you doing?

Love,

Jane

Dear Jane,

I didn’t know how I was doing, in truth, until just today. When the university where I teach closed for spring break, and moved classes online until sometime in April, then told us we wouldn’t return till fall, the little cold I’d picked up began to get worse. I was coughing, and feeling tired, and then one night had a low-grade fever. I called a hospital hotline staffed by kind and helpful souls, and two days later found myself in an open-sided tent underneath a huge blossoming pink magnolia in a garden at Bellevue, taking a test for COVID-19. It was important, I thought, to know. The doctor who swabbed my nostrils—a quick discomfiting sensation, not painful really—had read my poems, and that made the process feel humane and personal. Though they told me I’d have to wait two days for results, I found myself checking the phone for messages obsessively; maybe I didn’t hear it ring, or no chime went off to signal a new message? By the second afternoon I called the hospital, who told me results were now taking five to seven days.

Those days. I live in a bustling part of Manhattan, but outside my windows vehicular and human traffic thinned and kept thinning, moving toward an uncanny silence. I walked with my dog every day, three long blocks to Union Square, and each time we’d pass maybe two people on our way from one intersection to the next. I had my online classes to teach, and bits of literary business, and Netflix, and a long novel, and cooking, but I felt the energy gradually drain from all of these. I love my apartment, with its high ceilings and its two great blessings, rare in older buildings: a working fireplace and laundry in the kitchen. But I felt caught, and a wind was blowing through my attention, and every time I seemed to center myself, that wind would come and send my mind skittering around the room again.

I slept more during the day, and began, when I was out walking Ned, to take pictures of the sudden explosions of the flowering trees. I snapped some photos at night, under streetlamps, so the flowers look like blurred hands moving against the dark, almost abstract. We haven’t had a real winter: dim and gray, and cold now and then, but no below-zero blizzarding; these bursts of flowers are the only snowy thing we’ve seen. They seem incongruous in the world epicenter of the novel virus, where our hospitals are on the verge of meltdown. But then I remembered that a virus is a sort of blooming, too. It doesn’t matter to spring what is thriving, only that thriving happens.

This takes me back to an earlier moment when we were considering whether a poem can be redemptive. To expect that of poetry would create an untenable pressure for the writer, and an inevitable disappointment for the reader. When John Milton announces in his ringing, uncontestable voice that “Lycidas, thy shepherd, is not dead,” it’s true that the poem has kept him in an untarnishing, golden music in whose thrall he cannot drown or age. It’s also true that he is dead. What’s shifted, for the reader, are the terms we use to name what we’ve lost, how we try to circumscribe it. The poem that elegizes things we never imagined we’d lose—like the common, essential bees—does nothing at all to bring them back.

Which does not mean that poem is useless. First there is much to be said for the articulation of common grief, which is why I resist the idea that poems of social concern only speak to the like-minded. Please, speak to my like mind! I become paralyzed sometimes by my grief for the creatures who should be with us on Earth. When I think of the polar bears, the lions, the astonishing variety of life that was here on Earth in my time, I’m tongue-tied. I can’t write about that. But you can. And William Merwin did, magnificently. Those poems don’t make their occasion better, but they lift their readers out of awful stunned silence and into a necessary, awake state of grief held in common with others.

On day five after the test, the phone call came, and I knew immediately, from the cheery tone of the health care worker’s voice as she told me this was her day to be the one making calls, that my test results were negative.

I’ve been flooded with relief, and felt the tension I was carrying, the protective way I was holding myself, gradually ease. I felt the space I inhabit become larger. The possible absence of a future has constricted what world I could see. And during this time, when I’m suddenly blessed and still in a city under siege but going about my business anyway, teaching online, ordering groceries, trying to get a break on my mortgage payment, there’s a poem of yours from Ledger I keep coming back to, one you perhaps wouldn’t expect, “Spell to Be Said Against Hatred.” These last three lines have been a sort of handrail for me:

Until by we we mean I, them, you, the muskrat, the tiger, the hunger.

Until by I we mean as a dog barks, sounding and vanishing and sounding

and vanishing completely.

Until by until we mean I, we, you, them, the muskrat, the tiger, the hunger, the lonely barking of the dog before it is answered.

It feels almost wrong to say anything after that. But then that’s how you and I earn much of our living, isn’t it?—talking about poems that speak for themselves far more completely than we can by paraphrasing them. When I thought the limit of this life might be drawing closer, this poem, and this passage in particular, were profoundly comforting to me, And it remains so now that I likely have more time. I move through my days thinking I’m a separate being, bound in space and time, and then I’m reminded, by your poems, dear friend, and by the ardor and abandon of the flowering trees, what our brave predecessor wrote, that “every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.”

Love,

Mark