At four in the morning a phalanx of black silhouettes set out across the desert: three people and a donkey headed west on a sinuous dustbowl trail. The yogurt bow of the moon had slipped behind the earth an hour earlier, and the trail wound invisibly through thick predawn dark that arced toward the horizon. All was still. To the south, the Big Dipper scooped out the mountains I could just skylight against the spongy, star-bejeweled March night.

Amanullah led the way. He walked the trail by heart, steering from a memory that wasn’t even his own but had double-helixed down the bloodstream of generations of men who had traveled this footpath perhaps for millennia. At a brisk clip, in dry weather, the eighteen-mile walk across the hummocked loess usually took about five hours. Amanullah had made this journey every two weeks since he was six or seven. Now he was thirty.

“If other people in the world walked as much as we do, and worked as hard as we do, they’d go crazy,” he announced. He paused for effect. “But we don’t.”

It was Thursday, bazaar day in northern Afghanistan. We were walking to Dawlatabad, the market town nearest Oqa, Amanullah’s village, to buy carpet yarn for Amanullah’s wife, Thawra.

For the next seven months, Thawra would squat on top of a horizontal loom built with two rusty lengths of iron pipe, cinder blocks, and sticks in one of Oqa’s forty cob huts. Day after day, she would knot coarse weft threads over warps of thin, undyed wool, weaving the most beautiful carpet I have ever seen.

If the eastern hemisphere’s carpet-weaving region that extends from China to Morocco were itself a carpet, and one were to fold it in half, Thawra’s loom room would fall slightly to the right of the center fold. Prehistoric artisans upon these plains were spinning wool and plaiting it into mats as early as seven thousand years ago. Since then, people here have been born on carpets, prayed on them, slept on them, draped their tombs with them. Alexander the Great, who marched through the Khorasan in 327 BC, is said to have sent his mother, Olympias, a carpet as a souvenir from the defeated Balkh, the ancient feudal capital about twenty-five miles southwest of Oqa. For centuries, carpets were a preeminent regional export, a currency, status symbols, attachés. When Tamerlane, who was crowned emperor at Balkh, was absent from his court, visitors were permitted to kiss and pay homage to his carpet, which they were instructed to treat as his deputy. And of all the Afghan carpets, those woven by the Turkomans—who are known as the Rembrandts of weaving—are the most valued.

Any rug merchant in the Khorasan will tell you: two factors determine the beauty of a carpet.

One is the density of its knots. The density that makes for a beautiful carpet is approximately two hundred and forty knots per square inch. This gold standard is at least as old as the oldest known carpet in the world. An experienced carpet dealer will count the knots by ear, running his fingernail across the hard ridges on the reverse side of the rug. The higher the pitch of the scraping sound, the finer the yarn, the closer together the knots, the longer the carpet will retain the luscious bounce of its pile.

The second criterion of a carpet’s beauty is as elusive and whimsical as the first is concrete. Once a dealer is done scratching and mauling the carpet to determine the density of its weave, he will flip it over and inspect the pile itself. He will not be appraising the elegance of the design. No. He will be looking for proof of human fallibility, the prized idiosyncrasies that make each rug impossible to replicate, unique. He will be looking for mistakes.

A devout Muslim will tie a few errant knots on purpose, for a flawless design would challenge the perfection of God. Most often, however, the mistakes are unintended, accidental. They are the artisans’ personal diaries.

Here the weaver ran out of burgundy yarn and switched to the cerise left over from some older weaving: the depth of color in the border changes suddenly. Here a goat ambled into the loom room and the weaver jumped up to shoo it away: the lotus flower grew an extra petal where she forgot the count of the knots she had already tied before she settled back to work. An ailing infant cried: a blossom is left half-finished. A neighbor walked in with the latest sex gossip from a newlyweds’ bedroom—the whole village knew the groom was just a boy, so what did you expect?—and the border runs doubly thick for a centimeter or two, so busy was the weaver laughing.

The merchant will find the unfinished petal, the too-wide line along the selvage, the rhombus almost imperceptibly askew, and smack his lips, and nod, perhaps imagining for an instant which mishap could be responsible for it. He will say: “Good.”

There are mistakes. The carpet truly is beautiful.

The first thread was white. A four-year-old girl strung it on a Friday.

Holding a ball of undyed yarn with both hands, Leila stood over a corroded iron pipe that rested on a pair of cinder blocks along the southern wall of the loom room. She bent down and, switching the ball from one hand to the other, hooked the yarn under the pipe. Simple sorcery: just like that, the pipe became the bottom beam of a horizontal loom. The weaving would begin here. Leila pivoted around elaborately and ran across the earthen floor strewn with goat droppings and chicken feathers and straw. She stopped at the pipe in the opposite end of the room—the top beam—and looped the yarn over it. With the great ceremony four-year-old girls can be so good at, her face solemn, her palms sticky and pinkstained with sugar candy, she ran back: under the beam the thread went. Up again: over the beam. The yarn crisscrossed halfway between the two pipes, marking the center of the future carpet. Back again. Up again, and then back, and up, and back, and up, and oops—she dropped the ball and it rolled askew on the floor and the yarn dragged through drying bird shit and dust and God knows what else and Leila dashed to pick it up and kept running, from the bottom of the loom to the top, 18 feet there and 18 feet back, up and down, back and forth, I’m turning I’m turning I’m turning I’m turning I’m turning I’m dizzy I’m dizzy I’m dizzy!

“Good girl!”

“Don’t you drop that thread again!”

“A bit tighter here, Leila jan!”

“Keep going!”

Amanullah and Boston squatted at either end of the loom and slid plywood chips between the pipes and the cinder blocks to adjust the beams’ height and level while Leila shuttled between them. Boston cheered on her granddaughter and laughed and uttered instructions and pushed the warps on the upper beam closer together with her fingertips. I asked her how many warp threads there had to be to weave a meter-wide carpet, how many times Leila had to shuttle between the beams. She said she never had counted them. She only knew what the warps must look like, feel like, remembered the density of them on the loom.

Do you own a carpet? Touch it. Feel for the sticky palm prints of a little girl on the warp.

Thawra’s will be a yusufi carpet, a diamond pattern her mother and her mother’s mother wove before her, on the backdrop of wars past. Under her thin fingers, almond-size flowers with ogival petals will shine in a field of ocher and deep maroon. Each flower will bloom from two hundred and forty knots she will tie by hand the way her foremothers did; each knot will be a temporal Möbius strip that ties past and present.

Thawra leaned forward and reached for a ball of weft. Plucking the strung wool like a harpist, she ran the end of a burgundy pile thread all the way around two warps, pulled on it, and, with a sickle, cut the weft an inch from the warp, making the first of one million one hundred and sixteen thousand knots. Each one protozoan, irreplaceable. And again. And again. And again. Deft, precise, rhythmical, re-creating a design that had been passed on for generations unnumbered. Yet Thawra’s carpet, like each carpet ever woven by a woman’s hand, will be subtly different. It will be hers alone: her future autobiography, her diary of a year, her winter count, with its sorrowful zigzags, its daydreamy curlicues, loops of melancholy, knots of joy.

There was something else, too. (This was a secret, and the weaver’s thin lips curved thinner still with a discreet and private smile. Not even Amanullah knew.) The bottom sixth of her carpet will be almost imperceptibly queasy, a two-foot-long chronicle of morning sickness. Thawra was two months pregnant with her third child.

Thk, thk, thk. Thawra’s sickle kept time with not one heartbeat, but two.

The women wove their carpet of whispers. I leaned against the doorway and took notes. A lizard skittered from underneath the loom and up a clay wall and disappeared. From time to time I would look up from my notebook to watch the women weave. From time to time they would look up from their loom to watch me scribble. Silently, discreetly, we studied one another. To each of us, the other’s craft unknowable, full of mysteries.

Sometimes we would catch one another’s eyes and laugh together without making a sound.

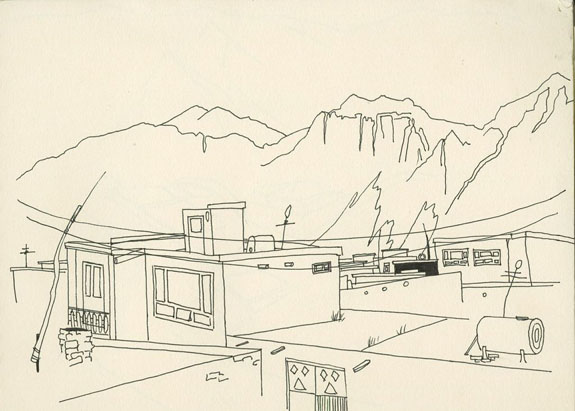

It was mid-afternoon, very hot. The whole village was quiet, stagnant. Everyone was either napping or weaving. No one was outside. The unpeopled landscape of Oqa was so sparse that each object stood out. Bed. Artillery shell casing. Donkey. Dung beetle. Tandoor. Time felt dilated, molten, distilled to its core: a wartime wedding feast for children. Armed nocturnal riders through a desert always on the cusp of bloodshed. Another spring at the loom.

Study your carpet. The hands of three generations of illiterate women created it. It is soiled by chicken droppings and stained yellow where the weaver threw her tea dregs at the loom. Its knots fasten wedding songs and women’s murmurs. The metronome of a sickle blade and the buzzing of noon flies. The whistle of a gale in the grass roof. An old woman’s breath as she, at last, sat down on the floor to rest.

The ninth lunar month of the Muslim calendar, the holy month of Ramadan, had begun.

“Here in Oqa there is no fast,” said Amin Bai, and chewed his cigarette butt over to the corner of his mouth.

“Why not?” I asked.

With the special patience one reserves for explaining simple truths to an obtuse child, Baba Nazar explained: “Look at us. Here in Oqa we fast every day of the year.”

He had taken his shotgun to the dunes twice that week, and twice he had come home empty-handed. Not even a rabbit for Boston to cook into a dark cottony stew. Each year the barren land around the village became more barren, he said—for want of water, maybe, or maybe because all the animals had been hunted and eaten. The spindly-legged gray chickens that had hatched upon Thawra’s carpet in July were still too small to eat. For days the family’s only sustenance was homemade bread and foamy camel yogurt and the almonds Boston would shuck with a large rusty pestle on the piece of tarp Amanullah had used that winter to roof Thawra’s loom room, and tea. In the house of Choreh and Choreh Gul the dastarkhan was emptier still—tea one day, bread the next, no almonds. Opium to take care of the hunger pangs. Baby Zakrullah had developed a respiratory infection, and his mother was too stoned to wipe the crust of green mucus off his upper lip. Only Hazar Gul remained buoyant through the hunger and the heat, and spent long hours in the half-light of Thawra’s loom room, squatting on top of the carpet, weaving sometimes, always smiling.

And in the loom room, which Amanullah had shielded from the hard sun with fresh armloads of dusty thistle, Thawra was running out of tan thread, the thread that made up the background for her carpet’s stylized flowers and trees and eagles, the thread that tied into the most knots.

“We need a kilo more,” Baba Nazar said. That was almost four dollars he had to produce—from where? “One meter is left. Winter is coming, we don’t know whether she’ll be weaving then. Maybe it will take her a month to finish. Maybe she’ll have a baby in a month.”

Thawra squatted upon the loom. Her calico dress hung off her thin shoulders and bulged very slightly around the compact swelling of her pregnancy. Behind her, the recently hatched chickens loped upon the tan weave between discarded candy wrappers and long-bladed scissors, and clucked. Baba Nazar leaned against the doorless entryway and clucked also, with worry. His eyes watered past the chickens and past his daughter-in-law, past even the striations of the room’s hand-slapped walls, fixed on the invisible boundaries of his village’s paucity.

Once the carpet is finished it will take flight from this fantastically brutalized land that clings to the violent tectonics at the thirty-fourth parallel. Amanullah will roll it up and cram it into his donkey saddlebag, and his father will take the familiar footpath across the desert to deliver it to Dawlatabad. A middleman there will sell it to a dealer from Mazar-e-Sharif, the largest city in northern Afghanistan, the modern capital of Balkh. After that, perhaps, Thawra’s carpet will be jabbed into the back of a beat-up taxicab, then tossed into the bed of a truck painted with dreamy pastorals, in which it will journey across Afghanistan’s war-racked landscape and over the border, through Pakistan’s implacable tribal areas, to the rug markets of Peshawar and Islamabad. Or maybe it will travel west, past the mass graves of Dasht-e-Leili, across the Karakum Desert, to the bazaars of Istanbul. Or else it will trundle in the trunk of a bus bound for Kabul, from where it will fly to Dubai, and from there, across the Atlantic Ocean until it alights at a dealership in the United States, the single largest purchaser of carpets on the world market. A wealthy patron will pay between five and twenty thousand dollars for it. Wherever her carpet ends up, for her work Thawra will be paid less than a dollar a day.

But in the meantime, she will weave. And as she weaves, fine clay dust will filter into her mud-and-dung loom room. Through the scrub-brush lath ceiling there will seep into the room particles of manure, infinitesimal flecks of gold from nearby barchans, the terrible black cough of her neighbors’ famished children, echoes of the war that jolts the plains and contorts the Cretaceous massifs of her land. A roadside bomb will go off, and the desert outside her doorless entryway will groan in response with the phantom footfalls of past invaders: Achaemenid and Greek, Mughal and Arab, Ottoman and Russian, British and Soviet. A speck of an American Navy F/A-18 strike fighter will catch a sudden sunray on its wing and for the instant it pierces the incredibly high azure it will become a ghost of a different glint: on Genghis Khan’s sword before it split the skull of a Bactrian housewife, on the barrel of a guerrilla’s jezail matchlock before it discharged at some subaltern of the Raj. Taliban scouts will appear on the path where Amanullah and I walked for yarn, then vanish again, the way all raiders come and vanish upon this eternal battleground.

Reprinted by arrangement with Riverhead, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc., from THE WORLD IS A CARPET: Four Seasons in an Afghan Village by Anna Badkhen. Copyright © 2013 by Anna Badkhen.