The first Trojan War Museum was not much more than a field of remains. Dog-chewed, sun-bleached, and wind-blown bones, some buried, many burnt—but the Trojans prayed there, mourned their dead, told tales of their heroes, asked penance for their mistakes, pondered their ill fortune, poured their libations, killed their bulls, etceteraetceteraetcetera. There were not a lot of Trojans left; but, all the same, they hoped for a better future, and they believed in the gods, so they made sacrifices. Children, cattle, women, you name it.

Enter Athena. Motherless daughter, virgin version, murderer of Hector and Ajax and Arachne, at least a little bit.

The dead added to the dead, she said. What do they expect us to do?

Whatever the Trojans may have expected or hoped for, the gods did nothing.

The first Trojan War Museum was abandoned after a flood, a fire, an earthquake, not necessarily in that order.

The dark came swirling down. The city disappeared. Again.

Sing to me now, you Muses, of armies bursting forth like flowers in a blaze of bronze.

Soldier: I begged for sleep, and if not sleep, death. I was willing to settle for death. Then again, I’ve never felt more loved.

He looked at his father, a veteran; his grandfather, a veteran; his uncle, a veteran; his sister, a veteran; and he saw his future foretold, no different than birds and snakes foretelling nine more years of war.

Think: museums turn war to poetry. So to poets. So to war.

You know, Athena forgot Odysseus was out there.

Oh Muses.

The second Trojan War Museum was built in approximately 951 BC, upon the site of the first Trojan War Museum, after Apollo—boy-man beauty, sun-god, far-darter, Daphne-destroyer-and-lover-too—looked upon the empty plain dotted with the same old bones—more bleached, more burnt, more buried, more chewed—and declared it a ruin of a ruin and a dishonor.

They are forgetting, he told Zeus. We must make them remember.

Zeus—master of the house, lord of the lightning.

You’re not wrong, Zeus said.

A museum run by gods is unusual, of course.

Ares argued for an authentic experience and so there was a room where one in ten visitors was killed and another in which vultures and maggots devoured the flesh of the rotting dead while dogs licked up their blood then turned upon each other.

The second Trojan War Museum did not last long.

The dark came swirling down. Again.

Soldier: I had a more ordinary war. I feel lucky, really. Though sometimes, when I talk to other soldiers, I feel like it wasn’t a real war and so I’m not a real soldier.

Think: would you rather be told how to use what you’ve got or be given what you want?

Think: would you want Achilles’s choice or wouldn’t you?

Think: glory?

History: a place for tourists to visit.

But what else could it be, really? The ever-present present?

The third Trojan War Museum was built on Mount Olympus in the approximate year of 602 BC, when Zeus—suddenly angry at the shifted tides of man’s attention—gathered to the cloud-white mountaintop those Trojan War mementos that were readily at hand. (He was never one to go out of his way.) Known first as Zeus’s Museum or Zeus’s Junk Drawer, the collection only evolved into what came to be known as the third Trojan War Museum under the guidance of the more circumspect Athena—gray-eyed woman-warrior-of-wisdom.

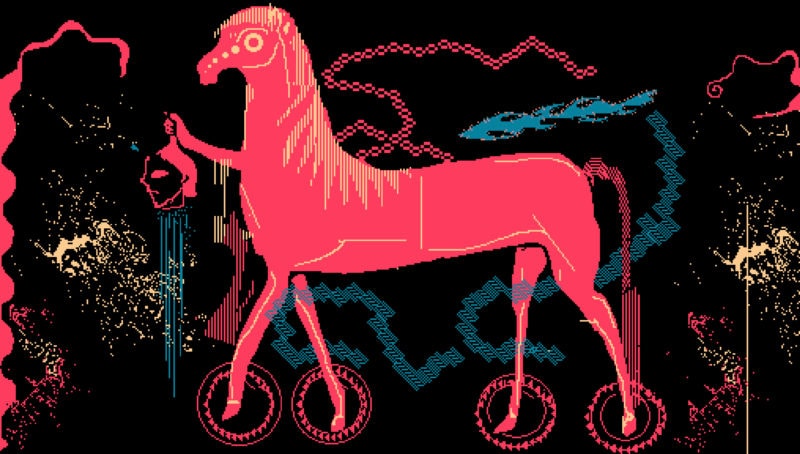

The museum labels provided insight into Athena’s opinions. Achilles’s armor, for example, was identified as “Odysseus’s armor, won from Ajax after the death of its former owner, Achilles.” The last item listed, and the culmination of Athena’s display, was noted only as: Horse comma Wooden. (Historians joke that Zeus brought the horse to Olympus in twenty-two pieces and Athena put it together in twenty, just to show she could.)

Visitors were naturally limited to those with access to Mount Olympus, and so there were none. Enter again Apollo, literally, into the belly of the great wooden beast. Night and day, day and night, Apollo lay inside, golden knees curled to golden chest, as if he did not consider himself alone, but rather crowded in with the men who had last huddled there, plotting brutality for the sake of civility. Apollo was interrupted only once when Poseidon—splitter of the sea, cracker of the coast, brother to the boss—popped his head up and in, swiveled it round, looked upon his nephew, and withdrew without comment.

Some historians believe Apollo’s equine confinement to be the mere equivalent of a teenage boy shutting himself in his room (who is to say, given immortality, when a god hits puberty?), but he had with him a long scroll, the first written record of Homer’s war, and he was studying it, particularly his own place in it—per Homer.

When finally he exited the belly of the ersatz beast, he went straight to his sister-of-sorts, the Curator comma Goddess, Athena.

The poet has made fools of us, Apollo said. Except maybe you.

I’ll look into it, Athena said taking the offending scroll from Apollo’s hand.

Soon after, on his own pilgrimage to Delphi (where, after all, should a god in search of himself go?), Apollo posed his thought as a question: Has Homer made fools of us? The oracle replied: The immortal is all. And though he should have known better, Apollo heeded the words and not their meaning, taking comfort where it was not offered. At least, for awhile.

But first, Poseidon, having exited the third Trojan War Museum unamused by Athena’s celebration of her sometime-favorite Odysseus, opened the fourth Trojan War Museum upon an island he’d created for the purpose. For the first time, two Trojan War Museums operated simultaneously.

Poseidon arranged his island-museum with sculptures and fountains, each of gold. Achilles seaside beseeching his mother, Thetis; Iphigenia upon her pyre, testing fate; and largest of all, not-all-gifts-are-good Laocoon captured high above the water in the arms of Poseidon’s serpent, mouth mid-scream, forever trying to prevent the future already past.

Off-shore, Poseidon built a full-scale replica Greek ship, gold, with life-size gold sailors. And there Athena—arborist and arbiter, celibate celestial, and the museum’s first visitor—got her revenge (part two) for Poseidon’s past indiscretions in her temple by taking pleasure upon one of the more fully-formed Myrmidons. (Though for the record, Athena remained, technically, virginal.)

The island had no plaques, no galleries of arms and armor, not even a building. Just Poseidon’s golden dioramas, and, running throughout, a pack of Horses (Live comma Wild).

It was surprisingly poetic.

There, too, was the iconic horse, this one gold. Though inexplicably it had its back to the surf; so that one had to ride backward to serve as sentry to the sea. And there, one morning, just so, was Apollo, the museum’s second visitor.

Remember when we built the walls of Troy? he asked his uncle. Remember the rough stone and the cuts on our hands? Remember the pleasure of the task?

Poseidon cupped a hand over his eyes to shadow the sun’s glint off the back of the golden god.

Was that the beginning? Apollo continued as he gazed out upon the water, his hands upon the horse’s golden rump.

In answer, Poseidon pointed a burly finger toward a dark-haired beauty (Live comma Buxom) stripped and bound to a rock on the eastern edge of the island, and said, there’s a girl if you want her. Then he left without another word.

Apollo sat in the garden, backward upon the horse, for half a day.

He did not like how Homer had made him screech like a lust-for-blood-cheerleader: Kill, you Trojans, kill. It hadn’t happened. Not like that. Had it?

He did not like how he could not remember. It had seemed so important at the time.

He disliked, too, how the gods seemed such ill company. If they were not friends to each other, what friends did they have?

And when it came time for Apollo to depart? He transformed the maiden on the rock into one of Poseidon’s horses. He thought it a kindness.

Still, she died with the rest of the herd, left untended without enough to eat.

The gods are not known for their sustained interests.

Soon enough the golden horse, the kneeling Achilles, the goddess-flavored Myrmidon, and all the rest ended up at the bottom of the bottomless depths.

The dark came swirling down. Again.

Think: what else are orders but dream-sent by gods?

Think:

- Has the arrow left the bow?

- If you were not fine, would you want to seem fine?

- Desert or jungle?

In other circumstances, Patroclus and Hector would have been friends, don’t you think?

Soldier: I don’t like to talk about it.

Soldier: To fight for what you believe in—your rights, your independence, your country’s rights and independence—means deprivations are gifts, the chance to prove your strength in the face of your oppressor. I welcome suffering.

Soldier: I said, I don’t like to talk about it.

The time between then and now is nothing, the space between here and there—nothing, the only prophecy you need is the past.

Once Homer’s war was found written on a mummy.

The fifth Trojan War Museum, the first to be widely known and visited, was opened in 1816 in Hampstead Heath.

Paris’s helmet strap snapped by Aphrodite so that Menelaus could not strangle him, Menelaus’s shattered sword, his leopard skin, the spear with which Hector killed Patroclus, a golden urn containing Patroclus’s crushed bones, the girl’s costume worn by Achilles when his mother hid him among Lycomedes’s maidens.

All displayed under glass, available for viewing at a pound a head. People came in droves.

None of it was real.

Oliver Godlenstone, a retired British banker who spent his youth criss-crossing the Middle East with a notebook and a small shovel, claimed to have personally dug these items from the earth of an undisclosed location, but in truth he had bought them from a man named Johan Turnkenman, who also claimed to have personally dug them from the earth of an undisclosed location. Godlenstone, despite his own lies, believed Johan Turnkenman’s.

Explorers must trust in the hospitality of strangers; it is the only way to venture into the unknown world. And ancient strangers often were received with hospitality, the very hospitality invaders took advantage of.

The fifth Trojan War Museum had its wooden horse as well. There was an observation deck on its back, soon famous for after-hours assignations, many conducted by an increasingly earthbound and melancholic Apollo, a son never meant to surpass his father, a boy-god meant never to become a man.

Eventually the fifth Trojan War Museum came to Zeus’s attention, and though he had done nothing with the actual artifacts still stored upon the cloud-white mountain, he did not care for fakes and forgers, and so he struck the fifth Trojan War Museum, in particular the observation deck of the fourth Trojan War Horse, with a bolt, effectively burning the entire estate down.

The dark came swirling down. Again.

But Apollo had an idea.

Athens 1821: He watched Greek soldiers throw enemy corpses into the well of Asclepios, Apollo’s own son who raised the dead and in so doing died by Zeus’s lightning.

And he watched Turkish soldiers do worse.

Crimea 1854: Apollo glimpsed the lady with her lamp at the Scutari hospital as the dying reached out their hands and called her sister.

Gallipoli 1915: Apollo watched the Turkish and Anzac troops throw food and cigarettes to each other during lulls in their shooting.

There was more. Much the same.

Soldier: I’ve never felt more significant than when I was in combat, but really I’ve never been more insignificant.

Soldier: I think if we could have gone home together—like the boys in earlier wars, who were all from the same town and stayed together and fought for their homes and went back to their homes—together—I think if we could have gone home together, we could have helped each other. But we got spread everywhere. The battalion was my home, and I fought for it, and when I left I didn’t really have a home anymore.

Tell me: who will build the memorial to those who died in a pile of the dead, thrown there while still alive? Who will memorialize those shot with their hands in the air? Who will mark the grave of limbs?

A lot of people are really angry.

Think: shouldn’t the immortals hold the world’s memory? Why else immortality?

Remember:

The overwhelming stench. The bone which did not withstand the blow. The twelve-boy blood-price for Patroclus’s funeral pyre. The scale which weighed Hector’s fate.

In 1986, Apollo declared he would open the sixth Trojan War Museum, known herein for reasons soon to be apparent as 6A.

It will be the book of the soldier’s coded heart, Apollo told Athena.

Go for it, Athena replied.

I want to learn what I am willing to die for, Apollo added.

Great, his sister replied.

He meant to convey the soldier’s experience to the non-soldier, the enemy’s experience to the other enemy, the home front experience to those on the war front; he meant to exhibit the wind, and the heat, and the cold, and the soldier’s devotion, the soldier’s fear, the soldier’s courage, the soldier’s boredom, the soldier’s rage, the soldier’s sadness, the soldier’s interest, and the soldier’s indifference. For once, a god meant to understand mankind. He wanted to display the human soul. But also soldiers’ bones chewed by dogs.

Apollo enlisted the interest of Olympus in his planning, and 6A turned into a research institute. This became the gods’ scientific age, in which they conducted experiments by appearing in people’s dreams and determining how best to change the course of human behavior. They conducted a test in which they saved the lives of every person engaged in battle for seven years running. It was a war without casualties. It went on without end.

6A lasted sixteen years, though with not much to show for it.

And still Apollo felt false. What he wanted was to be a soldier, to hold the museum of experience inside his own heart.

The dark came swirling down.

Baghdad, Fallujah, Ramadi, Tikrit. Apollo went to war.

Think: which side did he choose?

But: are there only two sides?

When you are immortal, how to prove that you are brave? What else to risk but your life?

Whenever Apollo stepped in to save his men, fate refused his effort. They died anyway, or worse.

Think: worse?

Shall I go on?

Soldier One killed Soldier Two in Place A; Soldier One killed Soldier Three in Place B; Soldier One killed Soldier Four in Place C; Soldier Five killed Soldier One in Place C. Soldier Six killed Soldier Seven and Soldier Five in Place D. Soldier Six made it home to die a later death.

Pop quiz: what happens when you replace Soldier One with Soldier Six?

Hector thought there was glory in the sight of burial mounds. He thought that men of the future looking upon them would think: There lies a man killed by Hector. And so they did sometimes.

How much suffering brings the end to arrogance?

Sack the city, kill the men, take the women.

Think: glory!

Soldier: You learn to believe you can do things—drugs, sex, killing—that are separate from your life and separate from who you are, that those things will stay with the fight. But then you try to go back to your life and who you are—who you think you are—and you’re not that person anymore, you’re those things you did.

Soldier: I do not want your gratitude.

Think: would you want your boredom punctuated by terror? Or would you want your terror punctuated by boredom?

Apollo went to war and he went to war and he went to war and he went to war. Each time he came home, he went back.

Who is the god of the IED and the RPG? Who is the god of Agent Orange, and heroin, and twelve-year-old prostitutes? Who is the god of orders gone wrong, ill-thought, ill-executed, and ill-reported? Who is the Mad god? Far-darter without aim, healer without healing. Time went untracked—dream, memory, prediction—all the same. A woman shot. A child shot. A soldier shot. A bow, a bomb, a gun, a knife, a gas, a drone. Dead wounded dead. An old manwoman a young manwoman an indeterminate manwoman was that a manwoman what was that a dog? The details different and all the same.

In the end, Achilles fought not for Agamemnon or Helen or Greece, nor even for Patroclus, but for Patroclus’s death.

How to memorialize the soldiers’ bodies? Those carried down the hills of Gallipoli upon a flood, the soft bodies of the long dead left in the fields of Antietam, the exploded bodies of the Middle East?

The constant light of the corpse fires? Bodies stomped into mass graves, the symbolic soldiers chosen for the tombs of the unknown, Union soldiers in Mrs. Lee’s rose garden, armies made of terra-cotta? Trees and flowers and blocks of stone? Apollo did not care for any of these options.

The only way to make people understand death was to kill them.

6B, known until now as the Lost Trojan War Museum, opened along the Dardanelles, in the year 2025.

The first object upon entering was the arrow Apollo guided into Achilles’s heel. The next object was the decapitated head of the museum’s last visitor. That display changed regularly.

Athena quickly stopped it. Apollo retreated from the Earth, leaving behind only a wooden horse full of corpses.

The dark came swirling down, darker, and again.

The desire to give in to fate, the desire to give in to pleasure, the desire to give into madness, the desire to give in to anger, the desire to give in to despair, the desire to give in to desire.

Interstitial anger.

Darkness in the god of light.

Apollo kept eternal youth and added endless experience.

Museum, mouseion, seat of the Muses, a place of contemplation or philosophical discussion.

Soldier: I wanted to come home and lead and serve at home as at war. But nobody wants me to serve and lead; they want the wounded warrior they can put on parade.

Soldier: You go to war thinking you’re putting your body at risk, but really it’s your soul.

The soldiers in the rear didn’t carry rifles, for it was assumed they would pick up those of the soldiers who fell in front.

The mothers and fathers of war do not have sons and daughters, they have soldiers, with whom they, too, could go to war, couldn’t they?

Think: what else is war but human sacrifice?

Soldier: Sometimes you’re okay. And then nobody believes you.

The Parthian shot. A boar’s tusk helmet. The oak of Dodona whispering prophecies. The lists of Linear B. The figure of eight shield and the silver-studded sword. The well-manicured battlefield. The desecration of a sacred space.

Words are the worst thing to tell the story of war, but how else to make myth?

Did you know homeros means hostage, Zeus’s bucket of thunderbolts is never empty, and the cypress is the tree of mourning?

Soldier: Eventually you stop testing yourself and you start testing God.

Think: are the dead safe?

The whole story could come only from an interrogation of millions.

Soldier: How you die, that’s how you are forever, that’s how you go into eternity? And what you said, that’s all the world is left with?

Ever-lasting last words.

Homer’s words have outlasted us already.

If you can stand it, the unburied will come to you and prophesize.

The seventh Trojan War Museum opened in Times Square in 2058; it was run by an American and silent-partnered by Aphrodite in high-heeled human form. The seventh Trojan War Museum had donors and blockbuster shows and a gift shop that turned over thousands of dollars a day. A marble statue of Paris loomed over the lobby. A nude of Helen dominated each brochure. Every fifteen minutes dozens of ticket holders climbed up into the horse’s belly, and sat in the dark, crowded and sweating, until the next quarter hour’s crowd was due to be let in.

The line for the oracle was so long a series of challenges were set along its twisting path.

The biggest seller in the gift shop was the tear collection bottle. The second was the Trojan condoms.

But then, after just a few months, the riots came. The oracle stood accused. The museum, Times Square, swaths of New York City were destroyed.

And the dark came swirling down.

The eighth Trojan War Museum, the current Trojan War Museum, is such a mystery. It opened its doors unexpectedly in a small town along the Aegean coast on July 9, 2145. Even the gods aren’t sure who started it. They have begun to wonder if there is some force larger than them. It’s been around nine years now, which is pretty long for a Trojan War Museum.

Visitors often cry in the eighth Trojan War Museum.

To enter, you must travel a long path to the underground. Some people can’t seem to leave. Or they come back repeatedly.

You can touch anything in the eighth Trojan War Museum; there are no glass barriers or alarms or even guards to stop you. Though what you touch might burn or bite or weigh on you. Sometimes what appears to be an ordinary sword turns out to be a piece of someone’s soul that once picked up cannot be put down. Sometimes a wind will blow in the eighth Trojan War Museum that will pin an unsuspecting visitor in place—sometimes it will hold them there for more than an hour regardless of their pleas. But an hour is nothing compared to the weeks ships sat in the Dardanelles waiting for the wind to change.

At the eighth Trojan War Museum, there is a room of lost languages, indecipherable symbols, and unidentified emotions.

It is rumored that the terminally ill can come to the eighth Trojan War Museum to choose death, that the Nereids will provide escort, and that there is a garden of bodies, a common but contented grave.

People sometimes disappear for more than a year and reappear in what is commonly known as the room of return but is really the lost and found.

The eighth Trojan War Museum seems to have a mind of its own.

Sometimes it wraps visitors in mist; one day perhaps it will not let us go.

There is a room for those who want to forget that allows them to forget; perhaps one day it will make us all forget.

Children left in day care are turned into a flock of birds and taken on a guided flight. Perhaps one day they will not be brought back.

The eighth Trojan War Museum has no wooden horse; and I wonder if that is our biggest clue. If the museum is the horse, then we are in the hours of peace between pulling the beast inside the city walls and the city being sacked.

I am not the only one who wonders. It is why the history of the Trojan War Museums has become so important.

Some say it is Apollo again, still trying. I fear the eighth Trojan War Museum might be run by Nemesis—true mother to the Circean Helen—spirit of fate and divine retribution, the ultimate ender of arrogance.

But even so.

If history is fate, we know what will happen, don’t we?

It is rumored that the ninth Trojan War Museum has begun already; Hades is preparing it in his underworld, a museum of the dead for the dead, a museum we can all visit one day, though not before our time.

But that will not be the end.

Because finally

after the over and over

there will be the tenth Trojan War Museum.

Have you heard of ephemeralization? The process of building more and more out of less and less? The tenth Trojan War Museum will not have a building, nor any objects, nor any visitors. It will be the air we breathe. Unavoidable. Born in us like instinct. A story we already know and need never tell again.

The After War instead of the Ever After War.

The true Trojan War Museum.

What are the odds?

Now there are buttercups upon the Trojan plain.

*

Excerpted from The Trojan War Museum: and Other Stories (August, 2019 W. W. Norton & Company) by Ayşe Papatya Bucak