It was just after the dawn prayer in the town of Ayn Al-Hosan, Eye of the Horse, and I was preoccupied and frustrated with my contact lens in the still, dim light. When I finally emerged from the rear of the mokeb, or camp, Seyed Jabar told me that two friends had dropped by from the billet half a kilometer away to have a cup of tea with me before heading out to the trench. In the days and weeks that followed, I would reproach myself again and again for not having been where I was supposed to be that morning. This was an absurd reaction to the death of one of those two men, since my being there to pour the tea would have made no difference at all in Ali Asghar’s fate the next day.

Over the past eighteen months, while following the Hashd al-Shaabi, the Popular Mobilization Forces in Iraq fighting ISIS, I’d become more superstitious in small ways like that—and the more superstitious I became, the more I feared loss. Western reportage about these men, if it existed at all, was faceless and made it seem like the Hashd forces were only out there for revenge. Revenge is not an unreasonable motivation, but it’s only a small part of the story. These men were, and are, fighting a fight that the rest of the world has a stake in. Every time one of them is “martyred” by an ISIS bomb or bullet, a worthy sentinel is lost.

Life at the Mokeb

The first time I visited this town, it was late fall and ISIS had been thrown out only the day before. They’d left in a hurry, leaving a lot behind, including a laptop I examined to find mostly just tedious urban battle footage. Three months later, when I came back, I was told that ten days earlier they’d nearly recaptured Ayn Al-Hosan. We sat straddling the line between Tel Afar and the Syrian border nearby. To create an escape route to Syria for its forces trapped in Mosul and Tel Afar, ISIS needed to clear this place. They did not succeed.

At the mokeb, the men served hot food and tea to the fighters coming from and going to the frontlines, just a few miles off in the two opposite directions of Tel Afar and the Syrian border. For me, the mokeb was Haji Hashem’s calls to prayer, Haji Yusuf’s infectious laughter, and Mohammad Misri tirelessly serving tea and displaying his 180-degree leg splits; it was also a place of onions and lettuce mounds, of man-sized pots of rice being steamed and chicken and meat being cooked over low fires all night; it was Iraqi men holding impromptu circles, dancing on one leg and turning into formidable poets of war.

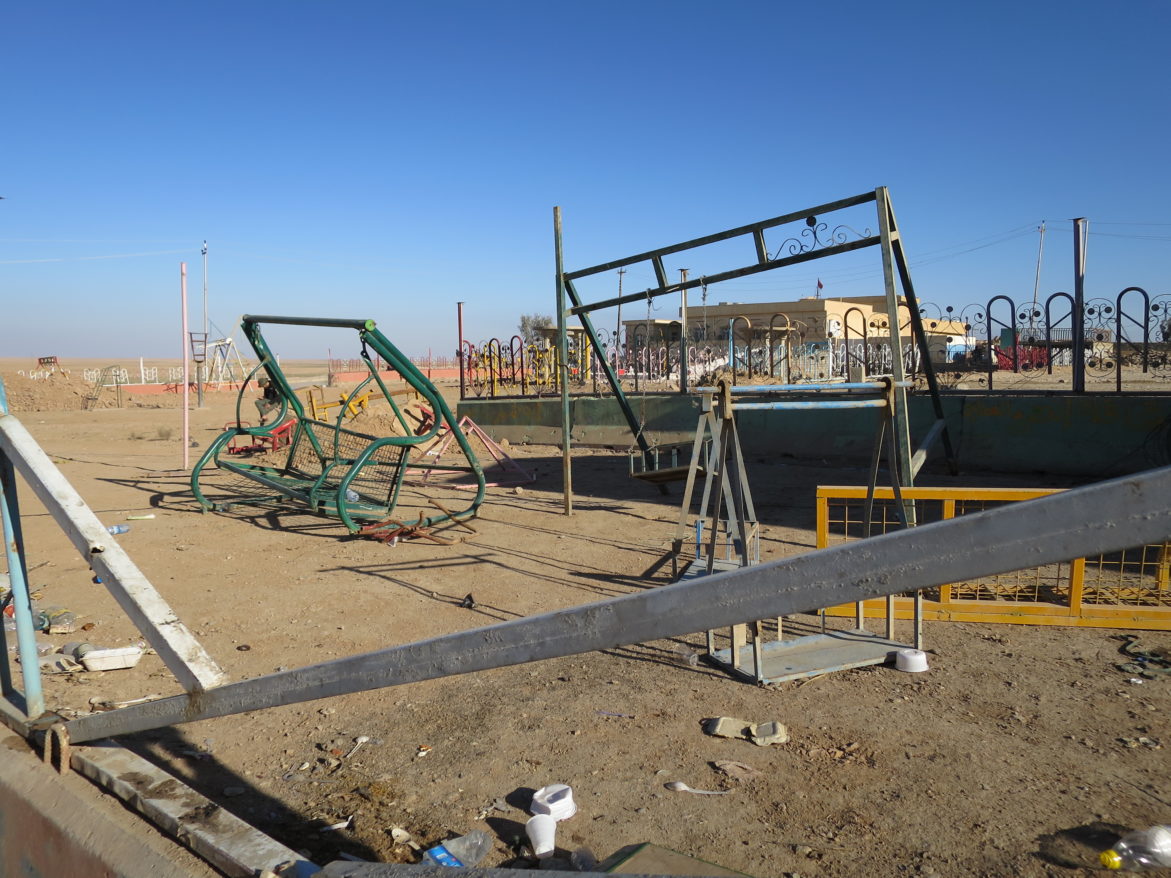

Devastation

A destroyed playground in the town of Tel Abta was a reminder that, contrary to common wisdom, life actually doesn’t always go on. Across it: typical smashed-up stalls by the main road and this tough-looking woman, the only one I saw for miles and miles around, dressed in military fatigues and a hijab.

Haider

He was always warning me to keep my head down in the back of the truck and not make myself such a tempting target. The last time I heard him yelling was the day after the battle for the village of Sharia. We had set out to bring the villagers and the Hashd forces food and water. One of the guys stationed there volunteered to show me the ISIS hideouts and tunnels that had just been discovered. It is not wise to step into these tunnels until they’ve been definitively cleared, and so when I came out Haider was fuming. Like always, I smiled sheepishly. Just the day before he had discovered my camera in a truckload of onions, tomatoes, and dates. The Hashd were making their final assault in the village and my camera and all the pictures I’d taken so far were lost. When Haider called out and waved the camera at me, I ran back, squeezed him to my chest, and planted two forceful kisses on his cheeks before hurrying toward the village. I knew without having to look that he was standing there nonplussed, doubtful of my sanity and contemplating his own tough luck at having to look out for me. Three days after I flew back to Tehran from Baghdad, I heard that Haider had been killed on the road.

The Coffeeman

You have to love the coffeeman. I became a regular at his mokeb and sometimes would imagine that this was not really 2016 but 1916, and Lawrence of Arabia himself would emerge from a nap under the tent holding a small cup and asking for a pour.

Waiting

Much of war is just that: waiting. Waiting and gadgets. One day, while we were sitting behind the dugout and waiting and waiting, a toy-sized drone appeared out of nowhere and hovered over us. A guy who had been playing with his mobile panicked and started to run. The waiting was broken; the drone, it turned out, was one of ours.

Seyed Jabar Al-Mamouri

I’d been tagging along with this fearless Shia cleric from Diyala province for a while. Several times a month he gathers donated food supplies from across Iraq to take to the front. When he comes upon refugees and freed populations, he does not distinguish between Shia and Sunni. He feeds and clothes anyone who needs it. When there is to be a firefight, he races to the head of the convoy of tanks and APCs. One day I watched as he directed two tractors creating fresh dugouts. At some point he just sat there, tired, in the line of fire of any sniper from the village down the road. I wanted to run out and “save” him. At nights my blue backpack and his prosthetic leg, which he acquired a long time ago, after stepping on a mine while fighting Saddam, would lean against each other and next to a fat gas capsule. One of those nights, before lights out, he pointed across the mokeb to the food being prepared for the next morning while shells blasted in the distance, “This is what war is, Salar: food and rockets. Write about that!”

Abu Azrael

Prior to the battle I took a couple of quick snaps of him with my mobile because he was armed to the teeth and looked impressive. Abu Azrael’s body count is legend by now. There are endless videos of him, character profiles, and maybe even a documentary or two. In those moments, however, I simply saw a man who understood the art of looking like an action hero.

Battle

By the time the final assault on the villages occurred, so much ammo had been spent tearing the place up that ISIS, despite the strategic importance of the area as an escape route to Syria, had already retreated. There was only one foreign TV crew here, reporting for an Iranian news channel. The Europeans and North Americans were all with the regular Army in or around Mosul—burdened with their flak jackets, helmets, deadlines, scoops, and per diems. I spent a good amount of time handing out bananas to the tired Hashd fighters.

The Inverted Flag

A viewer unfamiliar with the Arabic script would not know that the black flag, captured from tunnels, hideouts, and bunkers belonging to ISIS, had been turned upside down. What does one do with the captured flag? Burn it? Stomp on it? Tear it to pieces? None of these are options, as the name of God (Allah) and his Prophet (Muhammad) are on that flag. The only thing to do then is to turn it upside down to denote the error of the ways of those men for whom murder became a pastime. In a picture, big Haji Sa’ad holds one end of the upturned flag, looks to the camera, and smiles his usual gentle smile, while young Mohiman, wearing a field cap, holds the other end. In a way, all the labor of a war comes to this moment.

Food & Freedom

The Sunni villagers had been in ISIS’s thrall for nearly three years. While Seyed Jabar handed the children dates and apples, I stayed in the back of the truck and gradually gave up trying to control the distribution of the rest of the food to the villagers. In another instance, the locals showed us a watering hole that ISIS kept strictly for itself in that parched landscape.

Ali Asghar

He harked back to an earlier era—to Iran’s war against Saddam Hussein in the 1980s and the kinds of unwavering soldiers you’d find then, plus a bigheartedness that seemed to come from years of hardship. He was also a crack sniper and had set out for Iraq to fight ISIS and protect the Shia holy sites. He’d bring his best friend along to the mokeb to see me because I’d told them it got lonely there at times without another Persian speaker. The battle for the villages in the Al-Abra area had just one casualty, Ali Asghar. I would only find this out afterward. When it happened, I was in front of the village schoolhouse, filming. A dozen fighters rushed out of the school carrying someone in a blanket. All I could see was a leg dangling out of that mass. I managed to capture a several-second shot of the leg and not much else, as there were too many fighters gathered around the unidentified casualty. Someone said, To God we belong and to Him we return, and the body was put in a vehicle and taken away. I moved on and deleted my unsatisfactory shot.

I spent much of the following days with the martyr’s closest companions from the sniper squad—Majid, Seyed Hassan and Seyed Javad—and struck by these men’s natural acceptance of death. Two weeks later, in the far south of Tehran, I pass under the poster they’ve made of the martyr on his street and soon I am explaining to his wife and her family that it was a booby trap that got Ali Asghar, not a countersniper’s bullet. It feels important that this distinction be made clear. But Ali Asghar’s widow’s thoughts are elsewhere; she looks away from me and her family and says, “Ali was too good for this world.”

I nod to let her know that I know.

All photos: Salar Abdoh.