In your first memory of him, you are four years old, and you are being suffocated.

You are under a blanket, having a pretend tea party with your best friend. She is his daughter and she is also four years old. The blanket is pale purple, made of worn fleece: those are details you remember clearly. It must have been winter, or at least late fall — chilly enough that the heat is blowing up through the floor vent, puffing up the blanket into a warm fuzzy womb.

You can hear the muffled laughter of her parents and yours. The four of them are neighbors, and best friends; he and your father have worked together for years. You hear his laugh come closer. Through the blanket, you feel his hand graze your leg. Then he pins the blanket to the ground, forcing you closer to the vent’s hot blast.

Even now, you remember it clearly: the cold bolt of fear, how the two of you struggle to knock his wrist aside. How you realize that your power is no match for his. In your memory, you can hear his laugh get louder. You understand that he knows what he is doing. And you understand that he enjoys it.

Even at four, you know what he is. He is a bad man. He is a man who likes to make little girls feel scared. And you know that he is a man who gets away with everything.

Another memory, once upon a time: your eighth birthday party, at a roller rink, the kind with UV lights and ’80s neon squiggles on the wall. Your best friend already had her birthday party there; you were so excited when your parents let you, too. The rink is oval, sprinkled with spinning dashes of light from a disco ball overhead.

At one end of the rink, there are booths for bored parents to sit in. As you and your friends skate, your parents drink diet sodas, chatting with your best friend’s mother. But your best friend’s father is on the rink, skating in laps.

You’re not a very good skater. But you are a determined one, breaking in your new rollerblades lap after lap. At one point, you skate toward the booths, waving proudly in the direction of your parents. Your mother looks up when the bad man approaches you from behind and grabs your hand. In that split second, you meet your mother’s eye.

You meekly shake your head. You beseech her with your eyes: Tell him no. Tell him no! She smiles wide and gives you two thumbs up.

The bad man grabs your hand. “I was on the varsity ice hockey team,” he declares, and accelerates. Your hand sweats; you plead with him to slow down. Gripping your hand, he skates faster and faster, and your fear is compounded by your mounting nausea. Slow down, you cry, but he doesn’t hear you, or pretends he doesn’t, as he drags you in lap after lap around the rink, your eyes blurring, your hands growing more slippery by the second. And then, speeding around one end of the oval, your hand slips away and you’re sent careening across the rink before you smash, hard, into the wall.

When you are nine, your mother divorces your father and marries the bad man. She does this even though you beg her not to. For your whole life, your mother has been your world; you can’t bear to be away from her. And she tells you, often, that you’re her best friend, too. She’ll inscribe that in the front pages of picture books she buys you: FOR EMILY, MY DAUGHTER AND MY BEST FRIEND. But now the bad man declares that your relationship isn’t healthy, and he schedules twenty minutes every day that you’re allowed to be alone with her. Special time, he calls it, and soon she uses the term, too. When special time is over, the bad man walks into the room and brings your mother to their bedroom. At first, your mother will object, but the bad man will shut her down: Emily needs to know that we are the adults, and she is the child. They’ll lock the door behind them. And then you’ll cry, puddled on the floor, ravenous for what’s been taken from you.

You’ll learn soon enough that the door, once shut, won’t open again. You will stop begging. And behind the door, you’ll hear the sounds of the bad man doing something to your mother, sounds that unlock something new in you, something that makes you at once angry and afraid. You’ll dread those sounds, which will reverberate through the floor beams into the ceiling of your bedroom night after night for years upon end, sounds which you’ll associate forever with very bad men.

But now, during your allotted special time, all you do is cry. I hate him, you sob, over and over, your body limp like a wrung-out rag. I hate him. It’s a plea at first, and then simply a statement, calcifying into the primary fact of your life. The bad man will define the rest of your childhood.

The bad man’s house is perched on stilts on the side of a mountain carpeted by redwoods and surrounded by silence. The bad man is a surgeon; in time, he will chair his and your father’s department. His house showcases his wealth: there are high ceilings with beams made of tree trunks, majestic picture windows that look deep into the forest. Late at night, in the bare, cold room where you sleep, you lie awake listening to the wind spiraling through the branches.

At the wedding, your mother and the bad man sing “American Pie,” the bad man’s favorite song. They tell you that “American Pie” is the family song, and they sing it every chance they get — at the dinner table, in the car — as if the song itself had adhesive properties.

It’s done: The bad man is now your stepfather. Your best friend is your stepsister; her little sister is your little sister, and your little brother is hers. You’re the kids now, as if it had always been. The bad man and your mother confuse and undermine the relationships between you, isolate you all in different ways. They haul the four of you to a photographer, make you sit, staggered, on a ladder. The photographer makes you lie in a circle, the tops of your heads touching. He forces you to hug each other, forces you to smile.

Your mother and the bad man make big prints of the photos, hang them in the living room. “We’re like the Brady Bunch,” they say, to anyone who will listen. They call your family blended, even though it is anything but: it is an angry, bleeding thing, with jagged edges and broken bones.

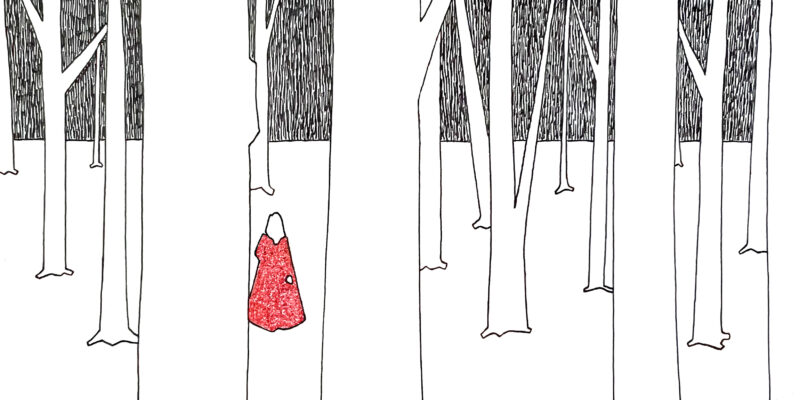

Some of your fondest memories in the coming years will be of reading in the woods. There’s one tree in particular that you love: an ancient, magnificent thing that’s fallen to the ground, creating a bridge over the dried-up creek beneath it. After school — first in fourth grade, then fifth, then sixth and seventh and eighth — you escape the bad man’s house and bring a stack of books to the fallen tree. You prop the books against your knees, curled in the tree’s gnarled roots.

You figure out which genres you love and which ones you don’t. You like historical fiction, stories of brave, precocious kids in troubled times. You like science fiction, and series about normal kids with everyday problems — strict teachers, bullies, beloved pets who die. You don’t like the horror series that are popular with your classmates, written in a second person much too visceral for comfort, where the protagonist is never in control. In those stories, the worst things always happen off the page, leaving you to fill in the most terrifying details.

And then there are the stories where, midway through, the premise shifts beneath you, where you realize that everything you thought you knew was false. You learn that these stories have what’s called an unreliable narrator. These are the scariest stories of all.

You prefer fairy tales, with their strange logic and their consistent casts of characters: unloved children and evil stepmothers, all happening some place outside of time. As you get older, you seize upon stories that play with their tropes: the castle as a metaphor for loneliness, the princess who saves herself.

And you’ll realize, too, that a person can tell a story any way she likes; that the same story — a little girl who loves to read — can be told as a horror story or a fairy tale, depending on the choices of the author.

It’s in those years that you begin to understand the expectations set by genre, the structuring of texts. You’ll come to learn that the beginnings are the most important, because they teach the reader what’s to come. The reader learns in the beginning of the story whether and how to trust the author, whether the logic is internally consistent, what the emotional terrain will be, what kinds of details will be left in and what kinds will be left out. Beginnings present the world of the story, what can happen and what can’t. A text’s beginning is its foundation; patterns and motifs are established, even if the reader won’t recognize them until later.

It’s just a few months after the wedding. Your grandparents — your mother’s parents — have come to visit for the first time. The bad man shepherds them into the bedroom he shares with your mother, where, above the bed, there’s an enormous drawing of a woman’s disembodied naked torso.

You and your brother are standing in the doorway watching as the bad man, holding a camera, shepherds your grandparents onto the bed. He props them up against the headboard, tells them to smile. They do. Then, you watch as he tells your brother — who’s tiny even for a six-year-old — to come. He reaches into the bedside table, then hands your brother a condom.

He tells your brother to stand in front of the bed, holding the condom in front of your smiling grandparents. Then: snap. You look away.

Twenty-eight years later, that photo will still be displayed in the living room.

That fall, you and your stepsister — who will soon no longer be your best friend — begin fifth grade. The school decides, wisely, to put you in separate classes. In a science unit, the bad man comes in to give a presentation on animals’ senses, as if he were some expert on perception.

You tell your teacher that you don’t want him to come into your classroom. You love your teacher, who is pretty and wears colorful silk pants and tells you that when you grow up you should become a writer. She says that he can give the presentation in the other fifth grade classroom.

The morning of the presentation, your mother and the bad man ask to meet with both teachers in the hallway. As your classmates are putting away their backpacks, you dawdle in the doorway, listening. The bad man, as usual, is talking. “I know the kids might have said some things about the divorce, all that,” he says to your teacher and the other fifth grade teacher, an older woman with a severe black ponytail. Your mother nods. “But you know how kids are,” he continues. “They’re so dramatic. And more often than not, they just make things up, just to get a rise out of us adults.”

You look at your teacher: she is nodding. Your heart begins to pound. And then you look at the other teacher. She is staring, fiercely, at the bad man. And then, after a moment, she performs a brief, tight-lipped smile, turns around, and walks away.

That winter, your mother and the bad man take you and the other kids camping. While the rest of them are setting up the tents, you walk off in search of a place to read. On the way, you pass what is now the family car, its back windshield coated with dust.

You stop. Your heart starts to race. You glance around; there’s no one there.

You place your right forefinger in the dust and slowly trace an F. You glance around again, inhale. Quickly, you trace a U, then a C and a K, followed by the bad man’s name. You underline it three times before glancing around. You scurry into the woods.

Hours later, your mother finds you leaning against a thick, maternal redwood. She leans over and puts her hands on her thighs, panting dramatically. For a moment, you stare at each other in silence.

She tells you to get up. You do. Then she barks at you to sit right back down.

She’s still hunched over when she opens her mouth. “You don’t mean what you wrote,” she says, breathing unevenly.

You blink at her.

Her eyes widen with fury. “Tell me right now that you don’t mean what you wrote.”

Your heart is racing. “I do mean it,” you say, with as much confidence as you can muster.

She inhales heavily, then exhales. She stares at you for a long moment. “If you want dinner, you’ll come back right now.” She turns around and begins to walk. Abruptly she stops and turns around. “He’s my husband,” she says sharply. “We’d like you to be a part of the family, but it’s up to you.” Then she walks off, disappearing into the forest.

Later that night, the bad man, you, and the other kids are eating hot dogs around the campfire. Lately, your mother has stopped eating all day until dinnertime, when she lets herself eat what she calls a healthy meal — a salad, usually, with dressing on the side — and then, as a reward for her discipline, one Drumstick ice cream cone. Your mother and the bad man are paying attention only to each other; he is mocking her as she eats her salad, telling her that she has a fat ass and flat boobs. “Like two eggs, sunny-side up,” he says. She is laughing, slightly, but she doesn’t look happy.

The kids are eating in silence. Suddenly, the bad man announces that everyone should sing “American Pie.” He launches in, his voice booming into the woods: A long, long time ago —

As everyone else sings perfunctorily, you pick up the ketchup bottle and squeeze. It lets out a loud fart.

When the song ends, your mother clasps her hands together. “Oh, that was great!” she exclaims. “We’re all having such a great time!”

This is a memory, or perhaps many memories braided into one: One afternoon, your mother storms into your bedroom as you’re doing your homework. She holds up the notebook you keep at school, the kind with the white and black mottled cover. “EMILY’S JOURNAL!!!,” you’d written in bubble letters, the I in EMILY topped with a shooting star.

You feel yourself redden.

She slams the notebook down on your desk. She grabs the Post-it she’s embedded in its pages, tears at it so violently it half-rips from the binding.

Yesterday a person from child prottective services came after school. She was acshully pretty nice!! But she came for a bad reason which is that there are alot of people who are being brainwashed and saying bad things about Mommy and You-Know-Who!!!!! Mommy told me not to say any thing bad so I didn’t. But she asked me what my favrite books are and I told her that my favrite author is Charles Dickins and she said that is very impressive. Also she

Your mother grabs the notebook. “You will not talk about what goes on in this house,” she seethes. “Not at school, not with your friends, not with your friends’ parents, not anywhere. What happens in this family stays in this family. Do you understand?”

You stare at her, blinking back tears. You know you’re not allowed to talk about it. But you thought you could write about it. Writing, you’ve begun to learn, is how you come to understand things best.

You nod.

Your mother softens. “Besides,” she says, “what you wrote here isn’t what happened. You should never write things that aren’t true. If you want to be a writer you’re going to have to learn that.”

You look up at her. “What do you mean it’s not what happened?”

She closes your notebook and shakes her head. “This stays in the family,” she says, and walks out of the room.

You are twelve; it is 1999. Your mother, the bad man, and the kids are sitting in the living room, watching President Clinton’s impeachment trial on TV. He is in trouble for lying.

Your mother turns to you and your siblings. “Do you know what a blow job is?” she asks. You don’t know, you realize, but you nod anyway.

The bad man is eating popcorn. “I don’t get why he went after Monica,” he says, to no one in particular. “Her body looks like a half-squeezed tube of toothpaste.” Your mother laughs nervously.

He turns up the volume on the remote and takes another bite of popcorn. “They should have a picture of that Linda Tripp woman on the bottle of Viagra,” he says. He adopts the affected voice of an infomercial salesman. “Look here if your erection lasts more than four hours.” He laughs loudly.

You have a big party for your bat mitzvah. All of your relatives are there — your grandparents, your aunts, all of your cousins. For the occasion, you’re wearing a gold-flecked black dress that your mom bought at Banana Republic. It’s floor-length, figure-hugging, with a neckline that scoops scandalously low. When you’d tried it on, your mom had smiled. “If you’ve got it, flaunt it,” she’d said, nodding approvingly.

In front of everyone, the bad man announces that it’s time for you to get your gift. He tells you to sit on the floor, then gathers everyone around you.

The bad man turns to your mother. “Kiddo, get the gifts, will you?”

She nods. Then she starts to bring in stacks of wrapped packages from the kitchen.

“We thought that, for an aspiring writer like you, one book wouldn’t be enough.” He pauses dramatically, looks around the room. “So we got you a collection to start your library.” You look at your grandparents; they are beaming at him.

He hands you present after present. The Best-Loved Poems of the American People. Great Poems by American Women. The Collected Works of William Shakespeare. You unwrap five, ten, twenty-five books. They’re beautiful hardbacks with thick, deckled pages.

It’s a great present; it seems like a thoughtful one. You know this in the moment, and you’ll concede this in the future. But the present makes you uncomfortable. Twenty years from now, you will understand: it’s a way for the bad man to attempt to take ownership of you.

He lifts out the camera from his neck, advances the film. Smile.

A few years later, the bad man will print out this photo, put it side-by-side with a photo of your mom when she was 13. In the photo, she is standing against a tree, smiling, wearing a t-shirt from sleepaway camp. The resemblance between you is astonishing. It’s more than a resemblance — you look like exactly the same person, captured somehow both in 1967 and in 1999.

When you look at your mother’s young face, you’ll feel an uncanny mixture of bafflement and recognition. You know what it feels like to have that face, those freckles and those red-brown eyes, that long dark hair that gleams auburn in the sun. At thirteen, you know that you look just like your mother, but that you are already a very different person. And you know, too, that you will spend the rest of your life making sure that that is so.

The summer before you enter high school, your mother and the bad man take the kids on a road trip to Nevada. It is 2000. Madonna has released her cover of “American Pie”: she’s taken the song’s skeleton and made it upbeat and danceable, entirely her own. On the two-day drive through the desert, curled up sullenly in the backseat, you listen to the song on repeat on your Discman.

One evening on the trip, you’re having dinner at a tacky Venice-themed restaurant in Las Vegas. Your left foot is throbbing. That morning, you’d stepped on something, and waves of pain had shot up your calf. With your mother watching, the bad man had examined it, then proclaimed that you were faking.

But it hurts, you’d said. Your mother had shaken her head: He’s a doctor. The entire afternoon, you’d been forced to go on a hike, hobbling behind the other kids, wiping hot tears from your cheeks.

Outside the restaurant window, you and the other kids are pointing out sights in Las Vegas. There’s the Bellaggio, or its cheap facsimile; there’s the Paris Hotel. The bad man taps your mother on the shoulder. “Look in that window there,” he says loudly. He grins. “That couple there. They’re freaky, but we’re freakier.”

You look at your mother. Even in the dark, you can see the shame in her eyes.

Nearly every morning when your mother drops you off at high school, she screams at you. She has a mantra that you won’t shake for decades: “Just because you’re smart,” she says, her face sheathed in anger, “doesn’t mean you’re a good person.” You steel yourself most days. On others, you enter first period with red-rimmed eyes.

In these years, you are never able to sleep, developing an addiction to Ambien that you’ll still be fighting twenty years later. Your thoughts circle around and around and around and around, taunting you with your deepest anxieties, turning your own mind against itself. In your early twenties, you’ll be diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder. But now, at fifteen, sixteen, seventeen, you take the thoughts at their word, experience them only as evidence that something is irrevocably broken within you.

Toward the end of high school, your friend tells you about a therapist; her mother hands you a check for a hundred dollars. You take the bus to go see her, then go back every week. But your mother finds out about it; to this day, you don’t know how. She storms in in the middle of your session, demands that you stop immediately. The therapist looks at you for a moment, then tells you to go with her.

But you go back, week after week. One day, your therapist tells you that the bad man called. “He seems like a very nice man,” she says. “And at the top of the medical field, as you know. He said that he taught you to drive.”

You stare at her. The words she’s speaking are facts, but they are not the truth.

“He cares about you, Emily. But he did describe your struggles with anger.”

Almost every evening, you scream at your mother, and your mother screams back at you. You’re angry, she says. You’ll wind up in jail if you continue on the path you’re on. And she tells you that your life is the way it is because of who you fundamentally are. You’re so heavy, she screams, and you believe her, even though you wear a size zero. You’ll never have true friends until you address your anger.

You’re miserable, she screams at you, over and over and over. You’re miserable.

You’re seventeen, sitting with your mother and the bad man at the kitchen table. It’s an absurdly long table, you’ll remember later. Your mother is sitting at one end, the bad man at the other. None of the other kids are there that night, for some reason. In your memory, inconsequential details fade; the ones that stick become the story.

You’re fighting about college. For years, you’ve been planning your escape: go to a college far away, somewhere you can learn to become a writer.

You’re trying to make the case to your mother to take you to visit colleges. You’re emphatic that the bad man cannot come on the trip. He and your mother say that he will, and that it’s not up to you. We are the adults and you are the child.

“Besides,” she says, glancing at him, “can you imagine us making all those arrangements by ourselves?” She’ll laugh, shaking her head. “Traveling all the way across the country, just the two of us? Booking hotels? Renting a car?” The bad man will nod vigorously.

You glare at your mother. “Fucking yes!” you scream suddenly, pounding your fist on the table. “What the fuck is wrong with you that you think we can’t?”

The bad man leans toward you. Slowly, he takes off his glasses. He lowers his voice, nearly growling. “And if you can’t change your attitude, we may have to reconsider footing the bill for a fancy-schmancy school on the east coast. No reason you can’t go to a state school around here.”

And then you stand up. You take your glass, still full of ice water, and you hurl it at the wall. It shatters. Shards of glass and ice skitter across the floor.

Calmly, the bad man sits back in his chair. He crosses his arms and smiles.

One evening in college, three thousand miles away from the bad man, you’ll be sitting with your roommate on her bed, talking. You’ll love your roommate fiercely; she is grounded and kind and very, very smart. You’ll trust her. You’ll mention — offhand, almost — that you know you’re an angry person, that it’s something that you’re figuring out how to deal with.

She’ll look at you, bewildered. “I don’t think of you as an angry person,” she’ll say. She’ll pause. “Like, at all.”

You’ll blink at her, swallow.

In your early twenties, you’ll be talking about your childhood with a good friend of yours. Alongside each other, you’ll start to identify as writers, encouraging each other and sharing your drafts. Her childhood, too, had been distorting. In time — not yet, but not too long from now — you’ll come to feel, more and more and more, like you are a reliable narrator of your own experience.

Over the next decade, you’ll process with her. “I was thinking about something the other day,” you’ll say one day, talking on your cell phone while walking laps around a pond. When you were in high school, you’ll tell her, your mother was hospitalized after an injury. She’d called you from the hospital, her voice quivering with fear.

You wanted to go to her, you’d told her. You couldn’t drive yet; you’d wanted to take the bus. You could be there in two hours. But then, at that moment, the bad man — the surgeon, already at the hospital — had walked into her room.

There’d been mumbling, and then a pause. Your mother had gotten back on the phone.

“He says you can’t come,” she’d said. She’d paused again. And then: “He says it’s serious. You can’t come.” You could hear the pain in her voice. Throughout everything, you could always sense each other’s pain. She’d paused. “I’m sorry.” She’d hesitated for a moment, and then hung up.

A few days later, she’d been at home. The injury hadn’t been serious, not like the bad man had said. Only many years later would you understand why he always made things seem so much worse than they were: he’d wanted to scare her. He’d needed your mother to need him.

Weeks later, you’d been fighting with her and the bad man.

In the middle of the fight, the bad man had turned his head to sneer at you. “You didn’t even visit her in the hospital,” he’d said. “In her hour of need, you couldn’t even make time to visit.” He’d shaken his head, performing disappointment.

Your mother had started to sob. He’d put his hand gently on her shoulder.

When you’ll tell that story to your friend, she’ll be silent for a moment. “Wow,” she’ll say. And then, after a pause: “That’s super fucked up.”

You’ll nod. And then, after a moment, you’ll laugh. “It is fucked up!” you’ll say. You’ll exhale in relief.

In your twenties, you’ll be in a café with your mother.

“He’s my husband,” she’ll tell you. “And he’s been my husband for a long time now. You need to accept that if you want to be a part of the family.”

You’ll shake your head in disgust.

“And also,” she’ll say, almost panting. “You’ve gotten heavy, Emily. Are you doing this just to spite me? To be like, ‘Oh, fuck you Mom, you want me to be thin and healthy, so I’ll just pack on pounds?’ The only person that hurts is you.”

You’ll inhale, feel the blood rushing to your cheeks. “Do you even hear yourself?” you’ll scream. “Are you aware that you sound absolutely fucking insane?” But you’ll wonder whether there is any truth to what she says.

Your mother will shake her head. “You need to get help for your anger. Or you’ll continue to be miserable.”

You’ll slam your fork on the table. “I’m only angry around you! You’re selfish and you were so fucking abusive. You’ve never once put my needs before your own. Not once in my entire life!”

She’ll pause. And then she’ll speak slowly, softly. “You weren’t abused,” she’ll say. “That’s a very strong statement to make.”

“And it applies!”

Your mother will be looking around the café. “You’re making a scene,” she’ll growl.

You’ll grow up to be a journalist. Your job will be to translate lived experience to text, to carve out narrative from seeping sprawls of trauma. I believe you, you’ll say to the people who’ll tell you their stories. I believe that you’ve experienced what you say you’ve experienced. It’ll be an attitude people will sometimes be surprised by, and it’s an instinct that you’ll be surprised by, too. No one will have taught you that it’s necessary, but you’ll know from the beginning that it is.

You’ll start the year Trump announces his run for office, as psychologists sound the alarm about the dangers of handing unfettered power to a malignant narcissist. You’ll watch that man’s rallies, his family standing meekly behind him, cowed in a way you’ll intimately recognize. You’ll scream at the headlines: Why is everyone enabling him? Why can’t they see the damage he will do?

And then, when he’s elected, you’ll recognize the way he identifies fake news, the preemptive declaration that anything his opponents say cannot be believed. You know how the Democrats lie, he’ll say. They’ll make things up just to get a rise out of the media.

You’ll be at an encampment in northern Mexico, interviewing a Salvadoran migrant who has sent her two young daughters to the US alone, a consequence of a policy created by his administration. Tomas las decisiones que necesitas para proteger a tus hijos, she’ll tell you. You make the decisions you need to in order to protect your children.

When you’ll review the recording, you’ll notice that when the woman describes the worst of her horrors, she speaks in second person. You’ll realize that it’s a narrative impulse you hear often from the people you interview. And you’ll understand that by transforming I into you, you distance yourself from pain. You share your trauma with the person who is listening.

You’ll be driving one day when that song comes on the radio. It’s a very long song, you’ll realize — absurdly long. You’ll listen to the lyrics, carefully, maybe for the first time. Did Don McLean even know what those lyrics meant? Drove my Chevy to the levee but the levee was dry. What the fuck does that even mean?

That night, you’ll call your friend, the one who understands. “I mean, how fucked up is that?” you’ll say, half-laughing. “To make us sing, at the wedding I’d begged her not to have, about — about the day the music died? For fucking real?” You’ll laugh again, but you will still be wincing.

Memories will come to the surface, often unbidden, often at the most unlikely of times. You’ll be swiping your subway card, or rinsing a bowl of cherry tomatoes, and you’ll think of that camping trip when you wrote FUCK on the windshield. You were a badass, you’ll think: a sad, trapped little badass.

You’ll be standing at the mirror, first thing in the morning, rubbing your face with a cold wet towel. And then you are 12, maybe 13. You go into your mom’s bedroom. You are always scared to do that, because that’s where the noises come from. But that afternoon, for whatever reason, you need to find her. You knock, and knock again, and then you open the door to their bedroom.

She and that man are sitting in bed, reading the newspaper.

“Emily,” your mother says. “Come here.” She looks at him, warily, then pats the spot beside her.

You sit.

He issues a command. “Get off the bed.”

You look at your mother; she averts her eyes. And then: the sudden surge of courage.

You don’t move.

He barks again. “Get off the bed.”

You swallow. “No.” The word has the taste of your own strength. You say it again, louder.

Your mother’s husband lunges at you. He is rabid. And you see how small, how small and pathetic he is. You understand it in the moment, and then, years later, you’ll understand it even more: that small, pathetic man has always been afraid of you.

Around this time, you’ll begin to think a lot about your mother, even though you’ll go long stretches when, despite her begging, you’ll refuse to speak with her. During those times, you’ll miss the good parts of her: how creative she is, and how she taught you to be creative, too. The ways she wants to know the events of your life. How she can be so fun, so supportive. The way she loves you — tumultuous, tortured, and also more deeply than anyone else ever has, than anyone else maybe ever will. She’ll tell you that she’s proud of you, that you’re kind and funny and talented. And you’re so good at writing, she’ll say. You’ve always been so good at writing.

And there are the times, few and far between, where it’ll seem like she’s slipping from his grip. She’ll send you cash so you can take your sick cat to the vet, and she’ll make you promise not to tell him. Or you’ll parody him — narrow your eyes, slowly take off your glasses — and, despite herself, she will laugh. At one point, she’ll tell you that she agrees with you, that him calling her “kiddo” is weird, and then she’ll tell you that she’s told him to stop. And you’ll think about how once, when you were in your early twenties, she called you from a hotel room, desperate: I’ve realized that he’s not actually capable of loving anybody except himself. That day, you’d felt hope. And then, the next day, she’d returned to him, denying forever after that she’d ever said what you’d so clearly heard.

A few times — and this is huge — she’ll fly to see you on her own. On these visits, she’ll beg: she wants to have a relationship, a close relationship, a relationship entirely on her terms, though she doesn’t call it that. In a moment of desperation, she’ll tell you that if she had to choose whether she loves him or her children more, she’d choose her children. And every once in a while, she’ll make admissions: that moving directly from your father’s house into his had been a mistake. But when you push her — do you remember this, or this, or this — she’ll do nothing but deny. What are you even talking about, she’ll cry. I don’t remember any of that at all.

And so it’ll go, that tortured dance between you and your mother, for years and years upon end. And then it’ll be March of 2020, and you’ll be in the area on a reporting trip. You’ll offer to stay at her house for just one night. And then, a few hours before you’d been set to arrive, she’ll call you. “He says it’s too dangerous,” she’ll say. “You know how much I want you to come, but he says that it could kill us all.” Her voice will catch, and then she’ll start to sob.

Months later, your mother will write how much she wants to see her sisters. You should get together outside, you’ll tell her. Just wear masks and stay 10 feet apart. You’ll be fine! You should see each other!

Almost immediately, you’ll get an email from him. There’s a 3.5% mortality rate for people in our age bracket. If your aunts and your mother and I all got together and got sick, there’s a 14% chance that at least one of us would die.

When you read the email, you’ll blink for a moment. And then you’ll laugh out loud. You’ll tell your mother exactly what you’re thinking: That’s not how math works.

Within hours, his response will come sailing through, six paragraphs full of fancy-sounding words that don’t make any sense. And then your mother will call you. I can’t believe you, she’ll say, her voice hysterical. He knows what he’s talking about. He’s a doctor.

A few weeks later, you make a decision. You will never speak to that man again.

As a writer, you’ll struggle to write endings. It’s never as simple as happily ever after — even when, in some broad sense, it is. Because endings are complicated: even when an ending maps easily onto experience — and then you never talked to him again — the ending of one story is always the beginning of another. In some ways, maybe, you’ll need a story to end before you can begin to tell it at all.

But you’ll be good at crafting beginnings — establishing voice, laying out patterns, establishing character quickly. You’ll be good at finding the scene to start with, the telling metaphor, the story in miniature: a little girl, barely more than a baby, being suffocated by a man. And you’ll have fun: you’ll play with tense and time and point of view, spin senseless lyrics into motif. But the writing you’ll do that you’ll come to love the most — the writing that perhaps stands out as most distinctly yours — breaks free from the confines of genre: an upended fairy tale, a horror story that turns into something else entirely.

As a child, you learned that, in the scariest stories, the protagonist never had the power. But now you’ll understand, in life and in your craft, that the protagonist is never in control. Only the narrator is.