The problem with my dachshund is that he pees.

Constantly. Unrelentingly. On rugs and furniture and laps.

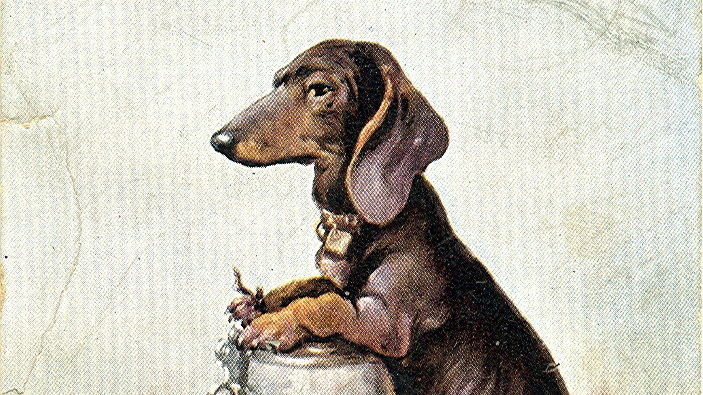

He looks up at you with those large, dark eyes, and attempts to communicate innocence. I know better. He’s a malicious bladder loosener. He knows that he’s a tiny dog in an enormous, chaotic world.

Piss is his weapon for bringing it down to his level.

My dachshund and I live in a trailer in the mountains. I spend most of my days in this trailer, ever since I lost my Walmart job.

In case you live in a big city, let me tell you about Walmart where I live. Maybe you think that Walmart is someplace to go shop when you’re out of money because you need a bookcase and they’ve got one that’ll do fine.

Where I live, Walmart is the place to be. It’s where you take your date on Friday night because it’s the only thing that’s open. Outside, it’s all dark mountains and snow, and you could go out and grab some beers in the woods, and sometimes you do, but that’s not how you want to impress a new date. Walmart is lit up, bright, and warm. You can stroll through the aisles and talk about the fishing rods and sift through the big bin of Hot Wheels cars. You can make it a dinner date by wandering the grocery aisles taking food samples, and that’s a good way to get full cheap if your date has a sense of humor.

It was the same when I was a kid, except now there are even fewer other places to take a date. We used to go swimming in the summer, but now you have to wait for a break in the thunderstorms, and search for a place where there aren’t any algal blooms. Even then, you basically have to put on mosquito repellent and hope, because if there isn’t dengue then there’s West Nile or chikungunya. Not that I have to worry about any of that, because I haven’t had a date to take to Walmart or anywhere else since I dropped out of college.

I lost my job because I told a customer that she was a fascist. Also, I hit her over the head with a foam bat. Also, she’s my mother, but no one cared about that when I got arrested for creating a public disturbance.

Mother comes to visit me and my dachshund in our trailer every Wednesday night. She brings casserole. At the sound of her voice, my dachshund jumps off of the couch and runs across the trailer into my bedroom. He may be small, but he recognizes contempt when he hears it.

She asks if I’ve been to church lately. “You should repair your relationship with Jesus,” she says.

I tell her that I’m naming my dachshund Jesus which means that my relationship with Jesus is just fine.

She doesn’t laugh. She pinches her lips tightly and looks around.

“Where is that dog?” she asks.

“Asleep,” I say. “On my bed.”

She prods the entryway carpet with the toe of her shoe. “You keeping things clean?”

She means, am I cleaning up after the dog when he pees? What would be the point? He just pees more.

“Yeah,” I say. “Everything’s fine.”

“Any bites on your job applications?”

“No.”

She clicks her tongue. “I suppose you want us to give you more money.”

Not want so much as need. I don’t say anything. She knows.

She unzips her purse and takes out her checkbook. She clicks open her pen with the edge of her nail. Mom and Dad aren’t rich, but they have steady jobs. They live in the house my great-grandfather built. It’s good, solid, and more importantly, paid off.

I could go live with them, but we mutually decided it was best for everyone if we lived far enough away from each other that no one would get hit by a foam bat over breakfast. Besides, they have the money they put aside last year to help with my tuition.

She hands me the check. Her fingernails are painted lime. She has old bottles of nail polish in every color. She keeps them until there’s nothing left but flakes.

She doesn’t let go of the check immediately. “I hope you know that we’re not going to support you forever.”

Really, all that’s happening is that she wants me to worry about whether she’ll take this check back right now. She waits a second and then releases it.

She says, “We worry about you, honey.”

I worry about me, too.

My dachshund doesn’t have a name. He’s just my dachshund.

I didn’t do it on purpose. I got him from the shelter after I dropped out of college in the middle of the semester and moved into the trailer. He was a house-warming present from me to myself. The last wave of floods had left a lot of rescued dogs with no place to go, so I said to myself I was doing a good thing. I needed to feel like I could do some kind of good thing right then.

It turns out college wasn’t for me. I got good enough grades in high school—not great, but good enough—but Mom “had a feeling.” She was worried I wouldn’t fit in. She was worried I’d change. She was worried I’d run away like her friend’s kid. Mom worries a lot.

It turns out that good-enough-but-not-great grades in high school doesn’t always translate to getting good-enough-but-not-great grades in college. It turns out that it doesn’t matter how naturally smart you are; studying is a skill, and I don’t have it. My professors and a couple of tutors tried to help me get it, but it was a lot to deal with on top of everything else.

Like the time my roommate threw up all over her sheets, and then just threw them out; and the time my other roommate ordered a bunch of takeout as a surprise, and then expected us to chip in; and the time one of my roommate’s friends said, “The college should stop admitting retards who don’t know stuff they should have learned in high school,” and my roommate replied, “Don’t be mean. She can’t help it!” and I wasn’t sure which one of them pissed me off more, so I ignored them both.

I’d told Mom not to worry about me changing, but it turns out, you can’t go places and not change. You can’t be around new people without picking something up. You might end up more like them, or you might not, but you change.

So I came home, found a job, rented a trailer, and got myself a dog.

When I first got my dachshund home from the shelter, I was just waiting for a name to settle. I figured he’d turn out to be fast and I’d call him Speedy, or he’d have a tendency to bark at night and I’d call him Chatterbox, or he’d be crazy about chasing cats and I’d call him Ferocious McGrowlmaster.

Instead, it turns out that the most remarkable thing about him is that he pees all the time. What am I supposed to call him? Sir Piss-a-Lot? The Urinator? Peeter Pan?

He’s the dachshund. That’s all there is.

Days have a rhythm. When Mom’s not over, I spend the evenings driving along the twisty mountain roads through the snow, looking for places to submit applications. There are gas stations and clothing stores and that diner that does good scrambled eggs. They all take my applications, but I know I go to the bottom of the piles. There are people out there with families to support. No one’s going to hire me over Joe when Joe’s kids need feeding.

The frustrating thing is that people don’t send rejections to your applications anymore. You don’t get a formal email with a graphic of the CEO’s signature at the bottom. You don’t even get a one-line text. It’s just long, empty silence, like staring into the mountains at night, with nothing to look back at you but stone.

The mountains are different now than when I was a kid. Pine and oak are replacing the birches and maples, and the last stands of red spruce are gone. No one plants over mine entrances to try to stabilize them anymore; the trees don’t take. The rivers are full of algae, and the low flows we get in summer just concentrate all the crap coming out of the factories.

During the decreasing number of days like this one each year—days when the world is all snow–that’s when things look like they used to. Snow conquers the mountaintops and turns every kind of tree anonymous white. It weighs roofs until they break, and catches between your eyelashes so that every blink is more snow.

It’s like a trap, the falling snow. Look out at the wide white and you start seeing how it’s like your life, stuck and getting worse.

Stuff doesn’t get better. When you’re a kid, you think it will, but it just goes to shit like the rivers.

I come home. My dachshund runs up to me. He barks and jumps and goes crazy. I pat his head. Piss rushes around his legs, sinking into the carpet. I edge around the puddle.

“Come on,” I say, and pour him a dish of cheap dog food.

I feel it that night while I’m asleep. Hot, wet, spreading all over the sheets. I scrape my eyes open. It’s two o’clock. The dachshund has climbed into bed with me. His eyes shine in the dark. His pee is everywhere. He’s standing in it, staring at me. I go back to sleep.

Mother comes over after church. It’s Sunday, and she only comes over on Wednesdays. She’s not supposed to be here.

She’s wearing a fuchsia sweatshirt that I gave her when I was in elementary school. It’s decorated with puff paint which is mostly peeling off. Her nails are teal this time with scalloped pink tips.

I’m on my way out when she knocks. I’ve got my keys in my hand. She’s got a wrapped-up chunk of leftover pot roast in hers.

She wrinkles her nose. “Dad and I agreed I need to check on you more often. I hope I’m not interrupting.”

The dachshund is sitting on the couch, trapped between her and the safety of my bedroom, clearly terrified. He looks up at me pleadingly, but before I can go help, he lets loose. Urine floods the cushions. Mom’s face goes white with fury.

People think my mom’s a sweetheart, and mostly she is—but she’s got an edge underneath that you have to be family to see.

She bolts to the couch. My dachshund decides it’s better to run past her than to be there when she arrives so he dashes for the bedroom. She pokes the clean edge of the cushion with the toe of her shoe. Urine sloshes in the folds.

“Mom—”

“I’ve had it. That dog is going back to the pound.”

“Mom.”

“Don’t ‘Mom’ me. I pay for this place. I say who gets to live in it. What have you been doing since you came home? You lost your job and now you sulk around the place. You can’t take care of an animal until you take care of yourself.”

“Mom, the shelters are full.”

“Then put it down.”

She stands, glaring, hands on her hips, her expression a caricature of anger. I shouldn’t leave her alone in the trailer with the dachshund when she’s just threatened to kill him, but I can’t stay; I just can’t. I push past her, out the door, keys still in hand, and start to drive.

Sometimes I think about what the world must look like to my dachshund. First, there’s the size thing. A couch cushion is probably like a twin bed. I think that could be pretty cool. Even my tiny trailer is probably like a huge farmhouse with a zillion rooms and a wrap-around porch.

But then, maybe it wouldn’t be so cool—because trying to get up on the counter would be like hiking a vertical slope. It’s not like you can get into better shape and learn to jump higher, because pretty much everything about you is dumpy. Your legs are ridiculous. Your belly and balls drag on the floor and there’s nothing you can do about it. You can’t get your own food. You can’t go outside on your own to shit. The human that is your only packmate comes and goes without asking for your say-so.

But at least you can change your corner of the world in one way. Even if it’s smelly and gross, at least it’s a sign you’re there. At least it’s a sign you matter.

It’s fifteen below when I pull into the gas station to fill up. My fingers feel numb on the pump even though I’m wearing gloves. When I go inside the kiosk to pay in cash, I see Dan is clerking there now. He used to come into Walmart. He has three kids who like construction toys. I think the oldest one had Dengue or something last summer, but I can’t remember how it turned out, so I leave it alone just in case.

Dan pulls a clipboard from the wall. “You want to fill out another application?”

I’m surprised for a moment, but then realize he probably assumes everyone is job searching. I grab a candy bar from the rack on the counter. “Is there any point?”

Dan shrugs. I take the application.

“You don’t have to use a paper one,” Dan says. “You can do it on your phone.”

“Paper’s fine.” I shrug back. “How’s your wife?”

“She is how she is,” Dan says shortly.

He’s not trying to be rude, I don’t think. It’s just, what are you going to say when things are going badly? There’s no point in complaining, but everyone’s going to know if you lie.

“How are you?” he asks.

I open my mouth, but then realize I’ve got the same problem he does. No one wants to hear complaining. “I’m great,” I say. “TV producer saw me taking the mountain and wants to hire me as a stunt driver. He says the big Hollywood secret is they get all their stunt drivers here. All the home-grown stunt drivers can do is weave in and out of traffic.”

Dan stares at me blank-faced for a minute, and then he starts to laugh.

I fold the application and stick it in my pocket. He nods toward it. “Good luck.”

I say, “Thanks.”

When I get home, Mom’s not there anymore. I worry for a second, but then I hear the jingle of my dachshund’s collar, and I know he’s still alive and present.

I pull the application out of my pocket and unfold it. Creases obscure the questions, but I know them all. I could fill them out without looking.

The dachshund rushes over. Before I can jump back, he lets loose, hot and yellow, all over my shoes. I take half-a-step away, my back against the door. I know I should go back out into the snow and pull off my sodden sneakers, and pick them up by the tips of the laces so I can make sure they don’t touch me. I should jump over the puddle in my socks, and rush the sneakers into the bathtub, then come back with an armament of cleaning supplies from under the sink. I should scrub until everything’s clean and new, and face tomorrow fresh.

But tomorrow I’ll still be here. Everything will still be covered in snow.

So I do it. I kick off my sneakers and tug down my jeans and squat next to the dachshund. The hot rush feels good. It splashes down my legs, ammonia and sour, and saturates the carpet. Our puddles mingle. He looks up at me and whines. I balance on my heels and reach down to pat his head.

You may not know it otherwise, but the two of us are here.