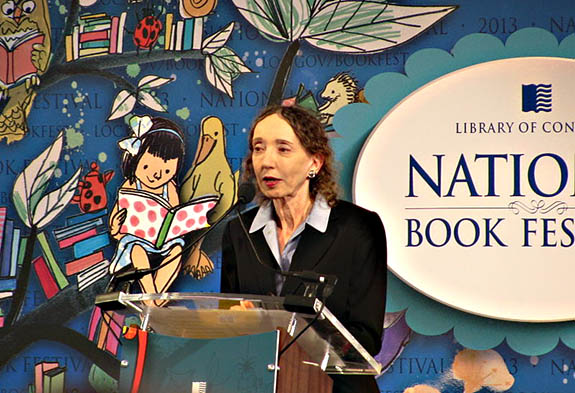

In a recent piece in the Washington Post, Joyce Carol Oates said: “I think of myself less as a writer than as a person who writes—or tries to.” This divorcing of the verb “to write” from the business of being a writer is an interesting one, and especially from an author who, with more than fifty books to her name, is one of the most prolific writers of our time. She’s also one of the most garlanded, having won—among other prizes—the National Book Award and the PEN/ Malamud Award for Excellence in Short Fiction. Her novels regularly grace the New York Times bestseller lists.

In the interview that follows with Richard Wolinsky, host of the Bookwaves radio program, Oates’s brand of playful modesty seems to extend even further: she speaks of her books as “toadstools, growing in the night.” The two most recent toadstools are The Accursed and Daddy Love, both of which were published this year. Whether she’s a writer or simply a person who writes, Oates continues to produce quality fiction at an astounding rate.

The Accursed travels back in time through the eyes of an elderly narrator investigating the so-called “Crosswicks Curse,” which afflicted the college town of Princeton, N.J. in the early 1900s. Kevin Frazier, writing in The Millions, called the book “a parody of a Gothic horror story, a mash-up of Dracula with samples from Hawthorne’s greatest hits.” Stephen King, writing in the New York Times, said “Joyce Carol Oates has written what may be the world’s first postmodern Gothic novel: E. L. Doctorow’s Ragtime set in Dracula’s castle. It’s dense, challenging, problematic, horrifying, funny, prolix, and full of crazy people. You should read it.” The novel exposes, Oates says, the racial and societal cruelties of the Gilded Age, when prominent whites “pretended to be good Christians, with all these pieties, but they were really vicious people.”

Daddy Love is a very different book. It absorbs the shockwaves of a violent kidnapping which takes place in the present day: five-year-old Robbie Whitcomb is snatched from the parking lot of a mall in Ypsilanti, Michigan. But as Wolinsky points out, both books take shape around a curse—whether implicit or explicit—and bear witness to the unlikely violence of the powerless, acts that seem to speak of Oates’ unwavering belief in young people’s capacity to rebel against and rise above the oppression of elders.

—Interview published courtesy of Richard Wolinsky

Richard Wolinsky: The Accursed began as a series of novels that looked at life during the Victorian era, which you started during the middle of the Reagan administration and have spent recent years working on. Was there any overlap between these periods?

Joyce Carol Oates: Oh yes. I think most works of historical fiction are about the time that they are supposedly about, but they’re also about the time in which they were written. When I was working on The Accursed, President Obama had been elected for his first time and that cast a certain light—or shadow—on some of the events in the novel, because it’s a novel that explores the social injustice of white bigotry against black people.

Richard Wolinsky: I understand that you didn’t quite get a handle on the book for thirty years. And then something happened after Obama was elected?

Joyce Carol Oates: Well, it may not have been that related to it, but something happened after I went back to it, I found a way that I could change the voice. The voice was too nineteenth century and I made it more modern, and I introduced the key: which was the moral blindness and refusal of the white upper class to acknowledge the rights of black people. And at that time in 1906 there were very few white people who would grant African Americans their full humanity. But my focus was on leaders, like Woodrow Wilson and church leaders, because they should have been leaders in their communities talking about the humanity of African Americans. It would have made a big difference. But what they did was nothing. There were racist mobs that were lynching black people, and terrorizing them, and these white leaders, these so-called Christians really didn’t do anything. The novel then took a focus that was going to talk about the accursed, the accursed being these white people.

I think in gothic fiction these supernatural creatures are meant to be symbols of a rapacious ruling class.

Richard Wolinsky: In addition to being accursed from a class perspective, there is also a kind of supernatural element.

Joyce Carol Oates: I think in gothic fiction these supernatural creatures are meant to be symbols of a rapacious ruling class. The original Dracula was a nobleman who prayed upon peasants, his own people, and it’s a very dark fairy tale for how the ruling class preys upon the people. That’s probably the clue to my novel—or all of my writing, really—because I’m from the working class. I’m from a class even a little below the working class, and so I’m sympathetic with what my parents and grandparents had to endure.

Richard Wolinsky: Could that be one of the reasons why you focus on the Gilded Era in so many of your works, because there the class distinction is clearer?

Joyce Carol Oates: It’s very painful, outrageous. The ways these people—by these people I mean the capitalists—exploited workers, including children as young as four or five years old. They pretended to be good Christians, with all these pieties, but they were really vicious people. You can’t be critical enough. The more research you do into the labor history of the United States, the more upsetting it is.

Richard Wolinsky: There are several real historical characters in The Accursed. Probably the most significant are Woodrow Wilson and Upton Sinclair. Did you choose to bring in Sinclair because he lived in the Princeton area where the book is set?

Joyce Carol Oates: Oh no, not at all. He represents the younger generation that’s counter to the conservatives. He’s a socialist and an atheist, and they are conservative and Christian.

Richard Wolinsky: Upton Sinclair at more than one point talks about when the socialist revolution happens. Did he actually feel that they were within a few years of revolution?

Joyce Carol Oates: I think he felt the revolution was coming. Remember in the 1960s when some of the Weathermen were in prison? They didn’t think they were going to be in prison for very long because they thought the revolution was going to overthrow the U.S. government and they would be let out of prison within the year. When the Iraq war began, didn’t they think it was just going to be a few months? Or that the Vietnam War was just going to be a year? Everybody has these bizarre, wrong, and underestimated beliefs. And so Upton Sinclair was probably facing a huge mob, they’re all shouting agreement with you, and you get a confused sense of your power. The revolution is here! It’s coming tomorrow.

Richard Wolinsky: How did the women deal with the fact that so many of their husbands were dead set against their getting the vote or having a say?

Joyace Carol Oates: Well, many of the women were the same way. Educated women of a certain class were the ones who wanted the vote. Complacent, Phyllis Schlafly-sort of women, as long as they thought they were protected by being married and having fathers and husbands to take care of them, didn’t particularly want the vote. So it wasn’t just male–female, it was a class issue. Working class women who didn’t have protection, who didn’t have financial independence, were the women who really had to work for the vote and suffered for it.

We’ve developed into a corporate democracy.

Richard Wolinsky: When I’m reading The Accursed, I’m also looking at how capitalism and class at the beginning of the twentieth century relates to today, when the income divide is just as stark.

Joyce Carol Oates: Yes, absolutely, and they want to hang onto their money. We’ve developed into a corporate democracy.

Richard Wolinsky: So many of your novels have genre twists to them. What role does genre play in being able to tell a political or social story?

Joyce Carol Oates: Genre can be used in many different ways. One of the best examples is the use of parable or fairy tale—as in Orwell’s Animal Farm. Animal Farm is quite a tour de force, and Orwell might have written it as a realistic novel with real people, but as it is, it’s a parable. When you pick up a mystery novel, you know there will be a mystery revealed—in the first chapter or maybe the first paragraph the mystery starts to open, and each chapter moves toward the elucidation of the mystery, and the final chapter must always explain, or in some way resolve the mystery. There’s a contract between the writer and reader in genre.

A novel like Daddy Love, which is a suspense thriller, starts with the first paragraph and goes through the novel and then it ends and there has been a very clear plot. It’s not like reading a more literary novel, where you vaguely know what’s going on. When I write a literary novel, I don’t feel obliged to make things explicit; it’s more that you are hinting that this is the end of the novel and there is a trajectory and that it will end this way. But when it’s a mystery novel, you’re supposed to end it, so that the reader is not baffled and frustrated.

Richard Wolinsky: It struck me that in Daddy Love, there is an engine at work.

Joyce Carol Oates: For me, Daddy Love is moving toward that magical moment, when suddenly the boy picks up a shovel and he hits this guy over the head. That is the climax of the novel—he has risen against his oppressor, he has knocked him down; he might have been able to kill him, but he runs away. Until that point, he’s been hypnotized and enslaved. But suddenly, he picks up the shovel, and the novel moves toward that point.

Richard Wolinsky: In The Accursed, Slade does the same kind of thing.

Joyce Carol Oates: I guess you’re right. Nobody has ever talked about these two novels together—it’s like you’re laying some transparencies together that the reader can see that the author can’t.

Richard Wolinsky: In response to questions, do you find yourself thinking, “That’s true, but it was never conscious. I was just writing”?

Joyce Carol Oates: I think that’s true for most artists. Vincent Van Gogh or Picasso do things that have a certain trajectory or pattern that they’re not aware of. If you call the artist’s attention to it, then the artist may see it immediately. It’s like Eugene O’Neill who was always writing about somebody like his father, or Hemingway writing about women like his mother. Shakespeare has a certain streak of misogyny that recurs from play to play—though the plays are all about different things. I call it a signatory element. It’s not that these people are necessarily repeating themselves, it’s something that’s deeply imbued in their being. That’s how you know it’s sincere.

I do tend to believe in the power of younger people to rise up against elders.

Richard Wolinsky: It creates a personal element that sets that particular author apart. Are there themes like this that appear in your work?

Joyce Carol Oates: I do tend to believe in the power of younger people to rise up against elders. I’ve always believed that; it was reinforced by reading Henry David Thoreau when I was thirteen, fourteen years old. It was important to me because he was the voice of adolescence as a moral imperative, of challenging your parents. That isn’t all that common in literature. Usually, it’s the older generation writing fairy tales to scare people. But Henry David Thoreau and to some extent Emily Dickinson—they’re the very spirit of adolescence.

Richard Wolinsky: And this is an element that runs through most of your books?

Joyce Carol Oates: Well, not so much in Blond, which was a tragedy about a way of life. But the other novels are more applicable to an ordinary way of life. In this country, we see the evolution of morality. Same-sex marriage would have been unspeakable, unimaginable in the 1950s, and now it’s talked about. The older generation is often against it, but younger people aren’t. You can’t take these social issues to get them out to vote—it doesn’t work in the same way anymore, because there is a natural evolution of morality and consciousness coming from the younger people.

By the 1970s, people were dazed with drugs, they’d turn on and turn off, so naturally the other side is going to rush back in. It’s like a pendulum swinging.

Richard Wolinsky: But that was always true in my generation—the Boomer generation—and we ended up with Reagan and the Bushes.

Joyce Carol Oates: But there was a recoiling against that. It was perceived by many people that the sixties went too far and were saturated with drugs and suicide. Things that were not socially healthy, and there was a reaction to that. But that’s what happened in the 1960s—it began with great promise and was then marred by excesses, and it sort of fell apart. By the 1970s, people were dazed with drugs, they’d turn on and turn off, so naturally the other side is going to rush back in. It’s like a pendulum swinging.

Richard Wolinsky: You’ve written fifty books, more…

Joyce Carol Oates: More. They’re like toadstools, growing in the night.

Richard Wolinsky: When someone asked if you write quickly, you said, “No. I write whenever I can.”

Joyce Carol Oates: I write for long periods of time. I do a lot of rewriting. To me, that’s pleasure. The first draft is difficult, like walking uphill through a thicket, but the second and third drafts are great pleasure.

Richard Wolinsky: Having written so many books, does each book change you at this point?

Joyce Carol Oates: Someone did ask me once—after one of my novels was chosen by the Oprah Book Club—how that had changed my life. For most people chosen, it does change their life. They quit their jobs, they fly away, they buy some car, or a house, get a divorce, but with me it made virtually no difference in my life at all because I was already settled. If that had happened when I was twenty-five, it might have made a difference. But I had a job I loved, I’m married, I had a house, I had a car.

Richard Wolinsky: But how about internally? Does finishing a book change the way you view the world?

Joyce Carol Oates: The Accursed dealt with many ideas that I’m very interested in, like Darwinian evolutionary theory and the confrontation of biblically received opinion. To me, those are ideas I’m very interested in, so I wouldn’t say the novel changed that—it was one way I dealt with those ideas. Tomorrow I might write something else that deals with that idea in a different way—it’s more that I’m working on certain themes and ideas and their expression.

To contact Guernica or Joyce Carol Oates, please write here.