SET FREE

My father knew doves

were a clenched fist

under veil.

My mother kept their bodies

like two rings,

the birds quiet.

My favorite song

was skittish. A goodnight

instead of star. The universe

pecked red and my father

set them free.

When I found their wings

like a jaw

a smudge of black sunrise

feathers gone and the thick

stick of blood missing from

their devoted bodies.

HOOKED LACE

I was always in the good car with my mother, the one

unable to be kept at the plant because of knives

in tires and cigarettes left lit on paint.

She hated the Z-28. She wanted four doors, not two

after a hard rain she hit every puddle and pothole.

Each splash, pasted and caked, left to dry

overnight like a sin. My mother collected Queen

Anne’s Lace, tall crowns masquerading as weeds

the cluster of petals small as a flea

like gnats accidentally inhaled —

a universe to another creature. Birds are not

safe until they fledge and learn

to distinguish between hemlock and carrot. Simple

as a seed taken for seven days to stop an egg from embedding.

LUXURY

I know I am not supposed to like it,

alone at the table, peeling the chicken

skin off, and into my mouth. The crisp

salt, sting of hot sauce

stuck to fingers, and I am eating

the prettiest piece first. I served no one

and ate entirely with my hands.

The puff and split of rice browned

in oil with onion and garlic. The sloppiness

of a hand crushed tomato, a jigsaw

of sweet and acidic. The perfume of cilantro,

no doubt stuck in my teeth and flesh of chicken

spurred to greatness with a rub of comino.

The tortilla torn apart, breathing

because its perfect edge was singed by fire.

The rinse and spin of digestion, a splash more

wine to soften when I think I am

a dandelion blown apart

curved like the bill of a hummingbird

and thigh. My heart is never still,

bloomed, outstretched, and

foolish. When I squeeze a cut

lemon, I close my eyes. Robins

can’t be captive, they die

within moments of human contact.

I’d rather let them fly

next to the orange butterflies, and

shake the dull sepia feathers

located on the belly, which are slightly

brighter on men.

WHAT GENERAL MOTORS DOESN’T PROTECT

I drive in wide circles, the click

of my steering is a card hitting a spoke

my father tilts his head,

all sound

is interruption.

The engine amplified

when played back from a brick wall.

My father worked

in a landscape

of machines lit by spark.

Sheared metal matches

seven days a week.

A meteor shower

too close to earth.

The wooden dowel he presses

against his ear, the other

end to the engine.

In bright sun my father

focuses on the maple,

tell me when the cicadas start singing.

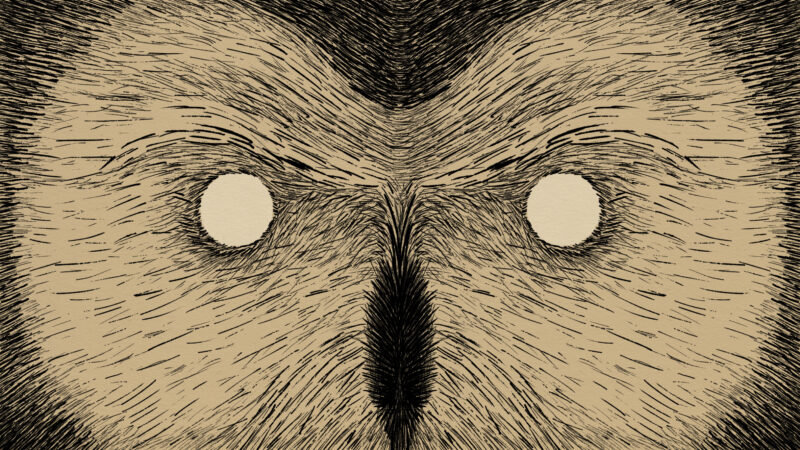

ENGINE BLOCK (EXPLODED VIEW)

1. Patternmaking

The owl doesn’t talk about the distance between him and Lake Michigan,

he tries to remove the coal ash from his ear tufts.

2. Coremaking

They rotate. As one owl is dragged out, another is brought in.

Do you think owls are afraid of water?

3. Molding

The owl thinks he hears Lake Michigan when he pours the melted metal in the core.

Lake Michigan is iron gray; where is the sun in all this steel?

4. Melting and Pouring

His feathers, sticky corn silk. Did the shakeout make a vibration, a wave burning sand.

The foreman doesn’t stop counting.

5. Cleaning

Not even the owl can see in the dark. A rogue wave buries a freighter.

After twelve hours he forgets light, he forgets water.

SECOND SHIFT

A thunder through the chest.

All metal and two hundred pigeons

cannot cover the fire

from rafter to machine.

The heat crawls under

hard hat

a slap of summer

so heavy

it is an engine.

The carbon in nodular iron

rings like crystal

along my father’s collar.

He pretends his sleeves are waves,

not the stiff denim

my mother irons, buttons,

and hangs. The delicate stitch

of my father’s hand removed

the white thread along the edge

of a pocket to make room

for his mechanical pencil.

I don’t know

if I will inherit

his shirt. After repeated

washing, it fades into a phantom

blue, like the eyes of my husband

who’s shirts have never been

stretched out like a wing

held and seared with metal

THE OWLS OF SAGINAW

When my grandfather caught

the long hair of women

preened in the attic

of his wings

with a layer of vaseline under

their lipstick kisses

a line of dewy

red tulips,

the only

evidence

of his hunt.

One, two, three.

He knew his

sons recognized

how cold

the moon was,

silk against skin. He has always

fed himself

never saying a word

about all those

yellow eyes, flashlights

who mimic him

and believe in prey

by sight.

RESURRECTION OF PREY

How the owl drags

her body slack and she offers her head.

What he spilts with his bill

are soft petals.

Her ear’s soft petal,

conscious of the snap.

Don’t worry,

the counter is clean.

Her neck,

wrapped and placed back in her body.

Head missing,

the heart and liver beside a candle

not death, but a blessing.

When she counts to five, he will

fold his napkin.

Bone, silver,

and hair. She is an earring

and molar. One pendant of

our Lady of Guadalupe.

A little water and the plucked

heads of geraniums wash her thighs,

she will save the trusses

blanched in her sweat

and leave sticky prints on his table.

He doesn’t like to be reminded of her,

this early in the morning.

There is nothing he can’t catch

and undress. Catch and undo, his silent flight.