In Gwadar, the first thing that struck me was the hills. The color of bone, they line the coast, hacked into straight lines as if hewed by human hands or mining. But it is harsh winds that have chiselled these sharp squares and turrets. In the local Baloch language, Gwadar means “gateway of the wind.” Below the hills, barren scrubland stretches out, a sandy moonscape under white hot sun.

We had just touched down at the airport, a dusty strip of tarmac serving as a runway, fronted by a blocky concrete building with a sniper positioned on top. “This will be an international hub—the biggest airport in Pakistan,” said the army official escorting us.

There were more than twenty of us, a delegation of journalists flown from Islamabad to Gwadar to see the outpost touted by officials as the next Dubai or Shenzhen. We filed into the waiting armored vehicles, discombobulated after a bumpy three-hour ride on a military jet, strapped in like extras in a war movie.

Glistening aquamarine sea stretched out on one side of the twisting road to the hotel, the colors saturated in the heavy sun. Traditional fishing boats, dhows, bobbed in the distance. Some half-built boats stood on the beach, turned vertical. Sudden bursts of life punctuated the long stretches of unpopulated land. Children and wiry teenagers in graying white vests, splashing water on their arms from shallow rock pools. A group of different-colored goats, leaping over the uneven surface of the beach, hair shining damp from sea spray. A man sitting in a cart pulled by a donkey, beneath a propped-up dhow.

As we turned, the beach gave way to sparse scrubland, the angular hills looming in the distance. The occasional hollowed-out brick structure served as a shop, the blue and red of the Pepsi logo daubed on its side, men in traditional clothing outside on stools. As we approached the hotel, signs of activity became less frequent, and then nonexistent. This was a sensitive area, close to the paramilitary Frontier Corps’ base and the site of the town’s only five-star hotel.

The Pearl Continental is perched at the edge of a precipice, atop a hill that looks as if it could disintegrate in heavy rain. The hotel is a boxy structure, all squares and oblongs like the hills surrounding it. This alien fortress on its perilous earthy mound looks down at the army base immediately below and at Gwadar town, an impoverished fishing settlement some miles away.

If Pakistan and China’s plans work out, this will be the unlikely epicenter of the new world order.

This plain and open field are mine

The barren plain and desert are mine

The hyacinth and the sweet basil are mine

The mountain and the dry desert are mine

This system and order are mine

I am the king of the homeland

—Gul Khan Nasir (1952, “Baloc u sa ir”)

There is a saying in Balochistan that every good tribesman should memorize thirty she’er, or verses, describing legends and transmit them to his sons. This way, the oral tradition lives on. In the modern era, poets have written down their compositions, rekindling ethnic Baloch fervor and chronicling continued revolt against colonizers with designs on this sprawling expanse of craggy mountains and barren desert. The largest and least populated of Pakistan’s four main provinces (making up 44 percent of the country’s land mass but 5 percent of the population), Balochistan is politically marginalized, extremely underdeveloped, and home to a low level but long-running separatist insurgency. Though today’s insurgents are splintered, they share a historic set of grievances: that Balochistan is being exploited by outsiders, leaving locals without a fair share of the region’s resources.

Gwadar is a remote coastal outpost in Balochistan, just eighty kilometers from the Iran border. Swathes of uninhabitable land swell between the cities and towns, making the distances hard to cross but providing ample space for insurgents and bandits to hide. While Gwadar has changed official hands several times—it was an overseas protectorate of Oman throughout British rule in India, and then, after independence, was incorporated into Pakistan—tribal loyalties have long been more important than the writ of the state. The people of Gwadar, like the people of Chabahar over the border in Iran, consider themselves first and foremost Baloch. What matters is the land. The word “mitti“—mud, soil, earth, land—carries huge significance. “Apni mitti” is more than simply “our land,” or “my land.” It refers to roots and identity, a sense of loyalty, faith, ownership, and worship, all of which provoke a passion that can demand any sacrifice—including one’s life. You belong to it and it belongs to you.

Dressed in his army fatigues and regulation beret, Lieutenant General Amir Riaz, commander of the Southern Command, a corps of the Pakistani Army, took the stage to enthusiastic applause.

“We are all sitting in Gwadar together, which, a few years ago, would not have been possible,” he said, as the claps died down. “It will grow, and continue to grow.”

We were in Pearl Continental’s conference suite, a large hall with dark-red carpets and rows and rows of velvet covered chairs, in the midst of a “seminar” on China and Pakistan’s plans to develop Gwadar’s port. Journalists, businessmen, and local residents had congregated to ask questions of the civilian politicians, Chinese officials, and military leaders pushing the project forward.

The Pakistani state, highly sensitive about Balochistan and in particular about its treasured cooperation with China, typically tightly restricts media access to the region. But this time, the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) had organized the press trip themselves, keen to display the open discussion to our delegation of mostly Pakistani journalists. This was part of a public-relations push, to show the nation—and the world—that Gwadar was soon to be open for business, and that all doubts about development there could be cast aside. They envisage a modern city, free from insurgency and full of luxurious hotels and shopping malls, with a major international airport and a range of secondary industries springing up around the port.

Our movements were tightly planned: the occasional authorized and closely supervised trip out of the hotel, and then back to the dazzling white of the Pearl Continental’s lobby. The hotel staff, unaccustomed to so much activity, rushed around manically as the reception filled with military top brass, an array of journalists and businessmen, and a steadily expanding contingent of residents. The rooms were imposing, with marbled bathrooms and sumptuous beds, large windows looking out onto the wasteland below, like a portal to another dimension. Those above the second floor had never been used before, and the only Chinese journalist attending saw a mouse scuttle across his floor, momentarily puncturing the grandeur.

On stage in the conference hall, Riaz was warming to his task. “The world opens here,” he proclaimed. “Gwadar will be a place of consequence.”

There were big cheers, but not everyone in the room agreed. When the question-and-answer session began, the criticisms came thick and fast. Would locals benefit from the development? What about the claim that the Chinese wanted to build a wall around Gwadar, to keep it separate from the rest of Balochistan province?

“Gwadar should be secure,” said Riaz, smiling. “But I can absolutely deny that we have had any request for a wall from anyone from China.”

A businessman raised his hand. “We have been colonized before,” he said, standing up to ensure he was heard. “We do not want to be colonized again.”

“Let me tell you,” said Riaz, his voice rising. “The Angrez [English] have gone. This. Is. Your. Country.” The room erupted in cheers.

For centuries, Gwadar was a small, unremarkable settlement with an economy based on artisanal fishing. But in 1954, a few years before it was purchased from Oman by Pakistan, the United States Geological Survey identified Gwadar as a suitable site for a deep-water port. Deep-water ports are geopolitically important because their depth allows them to accommodate larger ships with heavier loads. Gwadar has the extra boon of being a warm-water port, meaning it doesn’t freeze over in winter. The Russians set their sights on Gwadar in the 1970s during the occupation of Afghanistan, but their vision did not come to fruition. It took three more decades and another superpower before serious steps were taken to develop Gwadar into a major port.

In 2001, soon after 9/11, construction on the first phase of Gwadar Port began. The project was driven forward by the military dictator Pervez Musharraf, and China was the majority funder. Gwadar had a population of just five thousand when the building began. But soon, this remote, impoverished fishing village was being touted as the new Dubai or Singapore. Never mind the spreading insurgency or the local resentments. After the construction workers arrived, so did the property speculators. Tribesmen sold off ancestral land at vastly inflated sums; some willingly, others under pressure. On this rocky land, businessmen and developers imagined luxury apartment blocks and five-star hotels. Amid the buying frenzy, the bubble inflated and stretched and in 2006—a year before the port was complete—it burst. Developers lost money, but locals lost their land: mitti sold off in the heat of the moment.

All the while, construction of the port went on. It was inaugurated in 2007 by Musharraf and the Chinese minister for communication, Li Shen. Musharraf gave a speech paying tribute to the friendship between China and Pakistan. This new seaport would, he said, open a major trade corridor from Pakistan, not just to China, but to Central Asia and Turkmenistan. He warned that Balochistan’s “extremist elements” must surrender their weapons or be “wiped out of this area.” Pakistani officials said that within a few years, Gwadar would be among the world’s biggest, best, and busiest seaports.

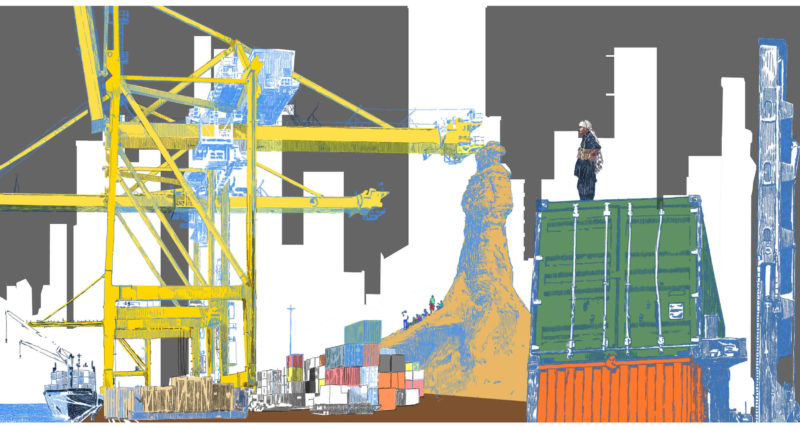

When I visited in April 2016, the port stood empty, its sharp lines and clean, freshly paved ground a striking contrast to the barren and rocky terrain beyond.

It is expensive to start a big infrastructure project, let alone one that is targeted by an insurgency, and for years investment was lacking. The funding situation, at least, changed in April 2015. Eight years after the port was completed, Pakistan and China announced a new plan: the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). This forty-six-billion-dollar scheme aims to link northern Pakistan and western China to the deep-water seaport at Gwadar through a 3,200-kilometer network of railways and roads stretching across Pakistan. The Karakoram Highway in northern Pakistan is undergoing expensive repair work to make it functional across seasons (at present, it is not unusual for rain or snow to halt journeys altogether). A new coastal highway connecting Gwadar to Karachi, 470 kilometers away, has been completed, reducing the journey time from forty-eight hours to seven. Gwadar is situated where the Arabian Sea meets the Persian Gulf, just outside the Straits of Hormuz and close to key shipping routes. Around 60 percent of China’s oil comes from the Persian Gulf via ships which travel over sixteen thousand kilometers to Shanghai. Gwadar’s port could reduce the distance to five thousand kilometers.

Today, the population of Gwadar has expanded to somewhere between eighty thousand and 125,000. The area is now subject to strict security, with a heavy Pakistani Army presence. On our visit, soldiers in army fatigues stood guard near the water’s edge, looking outwards but also keeping a close eye on journalists straying too close to the military ships. The Pakistani guards inside the development had rifles slung over their shoulders. Their black t-shirts flaunted “No Fear” in gaudy white bubble writing.

This is one small part of China’s ambitious One Belt, One Road initiative that aims to build cooperation and connectivity between China and Eurasia. If China succeeds in establishing its new Silk Road, it will have achieved in a few years what Russia failed to do in centuries. In November 2016, some months after my visit, the first shipment of goods from China left Gwadar for Africa and the Middle East, making the port formally operational. A collection of Pakistani and Chinese officials gathered to wave it off. “Today marks the dawn of a new era,” said Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif. But there’s been limited activity since. And officials say the port will not be “fully operational” until 2030.

Politics in South Asia are often driven by competition and the fear of encirclement. India, afraid of being surrounded by China, has moved to establish its own trade route to Central Asia, with a deep-water port at nearby Chabahar in Iran, and an equally ambitious road and rail route going through Afghanistan. There is speculation that China’s true aims in Gwadar are not economic but naval, and that the port at Gwadar is a cover for Beijing to keep an eye on Indian and American naval activity in the Indian Ocean.

While these geopolitical wranglings continue, Gwadar is about to see radical change. In addition to the main CPEC project, the China Overseas Port Holding Company has just begun construction on the two-billion-dollar Gwadar Special Economic Zone, modeled on China’s Special Economic Zones, areas which manage their economies in ways designed to attract outside investors. Officials predict that the population will swell again, to two million people, including twenty thousand Chinese workers. With them will come development and jobs. If all goes according to plan, Gwadar will no longer be a remote outpost in a remote province, but a central point of transfer between Pakistan and global markets, a place where journeys begin and end. Theoretically, two remote places will be transformed. The marginalized and restive western Chinese province of Xinjiang will be connected, overland, to Gwadar, which in turn will act as a portal to the Middle East and the Persian Gulf.

Officials and developers envision this desolate, dramatic landscape transformed and tamed. Yet Gwadar suffers such intense poverty and water shortages that a recent spate of robberies targeted bottled water. As residents of China’s Special Economic Zones would attest, top-down development often exacerbates economic inequality. The dream is to build an international trade hub and glamorous destination on top of underdeveloped scrubland. But scrubland to an outsider is mitti to inhabitants who have raised generations on this soil—and their place in the new story of Gwadar is as yet uncertain.

Is this a crime that we were born Balochi?

Is this a crime that Balochi is our language?

Is this a crime that also in our country

Our poems are composed for our heroes?

—Gul Khan Nasir (1971, poem from Grand)

Balochistan’s great twentieth-century poets all deal with themes of rebellion, anti-imperialism, and Baloch heroism in the face of exploitation. Their words, which built upon the rich oral history of this primarily tribal and illiterate society, give great insight into the Baloch mentality. Many of their poems, railing against oppression from other Pakistanis and foreigners, could have been written today.

Ever since Pakistan was formed in 1947, Balochistan’s alienation from the state has been a constant. A year after Partition, in 1948, the military forcibly annexed Kalat, in south Balochistan, after a pro-independence uprising, setting the tone for the continued militarization of the province. In the intervening years, Baloch alienation has sporadically led to rebellion, including a full-scale insurgency in the 1970s. In between, low-level resistance has rumbled on. This is a society that has always been made up of small polities, and today there are over 140 Baloch tribes. This means that Baloch nationalists—who come from different tribes and have different priorities—do not speak with one voice. Some are full-blown separatists, demanding a new independent state. Some simply want more rights within a federal Pakistan. While no Baloch rebellion has extended to the entire province, or even mobilized more than a handful of tribes, mistrust of the existing political order is widespread.

A key grievance is that Balochistan’s rich resources—coal, natural gas, and perhaps even petroleum—are exploited by central government. Federal money is divided between Pakistan’s provinces according to a strict calculation based on population size, which privileges the densely populated and already wealthy Punjab and disadvantages Balochistan. This historic resentment has led to the murders of so-called “settlers,” Punjabis who have often lived in Balochistan for generations. According to human-rights groups, more than one thousand of these non-Baloch citizens have been murdered since 2006.

This fury about the mitti—the soil, honor, and lifeblood—being abused by outsiders is compounded by the fact that the Baloch might already be a minority in their own province. At least a quarter of Pakistani Baloch live elsewhere in the country. (Karachi, in neighbouring Sindh province, is the center of Baloch nationalism.) Continued conflict in Afghanistan has bolstered an already sizable Pashtun population, and this inexorable increase in immigration—refugees on one side and economic interlopers on the others—plays to historic fears of being outnumbered and diluted.

In between speeches in the conference hall, I sat with Abdul Malik Baloch, chief minister of Balochistan from 2013 to 2015 and a former president of the National Party. We drank watery instant coffee in the bustling dining area of the Pearl Continental as other delegates walked past, taking selfies and comparing notes.

“Generally CPEC is a good thing, but we Baloch are very sensitive about our identity,” he told me. “It is a big area and a small population. We are appreciative of every investment but cautious about being taken over. They have to let us benefit from the development. The benefits should go to every last fisherman, not only to the neoliberal economists.” He paused, taking a sip of his coffee. “If not? We resist.”

Suddenly, an enormous octopus was projected onto the screen in the conference room, large lettering at the end of its tentacles reading “NATIONALISM” and “SUBNATIONALISM.”

“We need to know what we are up against,” said the army official. “Lack of integration is the cause of internal disturbances in Balochistan. These grievances have been exploited by subnationalists. Today things are much better. Balochistan is all set to exploit its full potential!”

The octopus remained, gormlessly and inexplicably beamed up onto the screen, as the official explained that through nationalism—promoting the love of Pakistan and a singular Pakistani identity for everyone—subnationalism could be defeated. Subnationalism, he explained, was a destructive force, selling the fictitious idea that people should identify more strongly as Baloch than as Pakistani. “The subnationalist narrative blames Punjab for deprivation and illiteracy,” he said. “Subnationalist actors abroad are involved in the exploitation of the common man, using him as fodder while enjoying affluent lives abroad.”

The octopus disappeared to make way for a video clip of a huge Independence Day event held at a stadium in Quetta, the provincial capital. “It was a conflict zone, but now things are much improved,” said a smiling woman in a colorful hijab.

“We have a slogan,” the official continued. “It is, ‘Long live Balochistan, long live Pakistan!’ This has taken the wind out of the sails of the subnationalists.”

He clicked onto the next slide, a circular chart detailing the military strategy in Balochistan. It was a crudely drawn dial under the title “People Centric Approach,” with a caption below reading, “Love Begets Love.” There were seven points on the dial. The first six all read, “Love,” in green lettering. The final point was in red. It read, “Selective Use Of Force.”

“We have the selective use of force because some people are not ready to lay down their arms,” the official was saying, before quickly reeling off a list of separatist activists who have been killed.

The military campaign in Balochistan has weakened the patchy and deeply divided insurgency; a tally of press reports found that separatist violence in 2015 fell by 36 percent to 194 attacks. But there is a darker side to this. Intelligence agents, often accompanied by the Frontier Corps, are accused of “disappearing” suspected militants into secret detention sites. Often, their bodies turn up dead in deserted areas bearing signs of torture. In 2015, the provincial government said that the bodies of eight hundred people linked to the insurgency had been recovered from 2011 to 2014. It estimated that 950 were still missing. In 2013, a UN fact-finding team noted claims from some in Balochistan that the number is as high as fourteen thousand.

He changed the slide to his finale. It read, in large letters: “DOABLE! MANAGEABLE!”

Pakistani officials are acutely aware that the new Gwadar development projects could spark disorder. It has happened before. After Musharraf took power in 1999, a new round of violent unrest began, partly precipitated by anxiety about government projects in the region: the initial construction of Gwadar Port and new military cantonments near an existing development, the Sui gas fields. The official line was that these bases were intended to increase ethnic Baloch recruitment into the armed forces, but to locals it looked like another effort to procure, colonize, and militarize their mitti.

The armed protest grew slowly, and gradually spread through different Baloch tribes. In this vast and barren land, inaccessible to independent observers or journalists, definitive facts are hard to come by, and the search for truth is undermined by an ongoing propaganda war between government and rebels. The details of the insurgency, even the number of active fighters, are hotly contested. One army official told me there were just a few hundred nationalist militants left; a Baloch journalist said they numbered in the thousands.

The unrest exploded after the rape of a female doctor by a military officer in 2004 at the Sui gas fields, in heart of the Bugti tribal area. Bugti tribesmen, led by Sardar Akbar Bugti, attacked the gas-producing plant at Sui, which provided almost half of Pakistan’s gas.

The Sui gas field is a flashpoint often cited by critics of the Gwadar development. It is in Balochistan, but the province has seen scant benefits. Highly paid jobs went to outsiders; the few local men working there are mostly in unskilled jobs. Most locals did not have the necessary technical education, and there was no attempt to teach them. Instead, they were sidelined. Balochistan receives significantly lower royalties than other provinces with more recently discovered gas fields.

In 2005, tensions ramped up. “Don’t push us,” said Musharraf. “It isn’t the 1970s, when you can hit and run and hide in the mountains. This time you won’t even know what hit you.” Other Baloch fighting tribes—the Mengals, Mazaris, and Marris— rushed to aid the Bugtis. The rebels released a list of demands, including more jobs for Baloch people, greater gas royalties from Sui, greater Baloch ownership of the then under construction Gwadar port, and no more military bases in the province. They were refused. Despite Musharraf’s scathing words, Sardar Akbar Bugti and his men did indeed take to the hills, hiding in a cave 150 miles east of Quetta. Bugti was killed by the army in 2006.

The death of this figurehead prompted many more heads to spring up, Hydra-like, from the severed neck. Most military men now agree the execution of Bugti was a disaster which greatly expanded support for the rebels, particularly the more extreme factions. An all-out insurgency followed Bugti’s death, and over one thousand people—rebels, police, soldiers—died.

And the war over information continues. Pakistani and Western intelligence sources agree that the Baloch insurgency is at least partly funded by India; even the rebellion for this contested land might involve some outside hand. The Pakistani government and military are intensely sensitive to criticism of their actions in Balochistan. Critical foreign journalists have had their visas revoked.

One evening, we drove to a local beauty spot, a cliff overlooking the ocean nicknamed “Sunset Point.” The earth here, atop the angular hills, was brown, a richer hue than the gray dust that seemed to cover everything below. Rows of chairs and sofas had been set out. Servants hurriedly served up hot samosas and large containers of tea on fold-out tables. I walked away from the surreal open-air tea party to speak to a Baloch journalist from Quetta.

“What do local people really think about the Gwadar port?” I asked.

He laughed and looked nervously around, pressing his business card into my hand. “I—we—think a lot of things. Let’s talk another time.”

A man, dressed in a conspicuously casual polo shirt and sunglasses, immediately wandered over. “Everything okay? Are you enjoying the sunset? Can I take your photograph?” He held up an iPhone and gestured for me to stand and pose.

Confused, I smiled for a photo. The man then stood by my side and took a series of selfies. I let this interloper put the iPhone away before introducing myself and asking what he did.

He looked, shiftily, from side to side. “That doesn’t matter. Think of me as the photographer.”

The journalist, by this time, had walked away and was standing alone, looking out to the sunset. The man looked after him, making sure he wasn’t coming back, and then made his excuses to me and melted back into the crowd.

The big event during my time in Gwadar was the arrival of General Raheel Sharif, then the chief of army staff and the most powerful man in the country. Pakistan’s military has run the country for more than half of its history. It’s not technically in charge at the moment, but in practice, it holds the reins of power. The federal government was noticeably absent, despite the potential for the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor project to change the narrative on Pakistan from almost-failed state to major regional player. Heavy army involvement in CPEC is understood as another sign of military dominance in Pakistan’s eternal civilian-military tussle, but it is also undeniable that the state usually leaves the Army to deal with this troublesome region.

The first sign that Sharif was on his way was the lack of phone signal—provincial authorities across Pakistan often shut down mobile-phone networks at the first hint of unrest or bomb threats. To be absolutely sure, the hotel switched off the wifi, too. The remoteness of our location was cemented by the sudden digital lockdown.

People crowded into the conference hall. The atmosphere was heady, angry, and tense: local people brought face to face with those proposing a radical change to their home. The disjunction between the Gwadar conjured up by officials and the present reality became difficult to avoid, as talk of the deep-water port gave way to more pressing anxieties. “People from Gwadar care about getting water,” said Mir Hammal Kalmati, member of the Provincial Assembly for Gwadar in Urdu, shouting to be heard over the applause. “Without this, we will die. We cannot make anything without water. We have no schools, no water, no help. We will welcome CPEC if it can do this work.” During a break, I noticed some local residents eagerly taking the bottles of water offered by staff, stashing them for later.

Sharif and his army entourage arrived in the afternoon, several hours late, swanning through the lobby like film stars on the red carpet. They sat down in the front row. The chief minister of Balochistan, Sanaullah Zehri, a portly tribal politician affiliated with the party of central government, took the stage. He commended the efforts of law-enforcement agencies in bringing kidnappings and murders under control. In the presence of Sharif, the most honored guest, the officials doubled down on their descriptions of Gwadar’s future greatness. But the presence of the people who would be most affected cracked the visage.

Balochistan is deeply conservative and patriarchal, and local girls from Gwadar sat separately from the men. During the question-and-answer session, three girls, not older than fifteen, stood up and walked deliberately from their spot at the back of the room right to the front. They stood facing the stage, their backs to Sharif and the other military men in the audience. Two wore headscarves, the third a full face veil. They explained that they were students.

“We are focusing on the port, but what about our water shortages?” said one. “A girls’ college was promised to us in 2006 and it has not been built. We hear about this port but development for the people is not happening.”

The chief minister laughed, appearing taken aback by her direct tone. “Well,” he said, as if he was speaking to a small child. “I am giving you my word that the college will be built.”

The girl in the face covering spoke up. “And tell me, why should we listen to you? You people get elected to high office so you can buy yourself houses and do nothing.”

The room was silent. Eyes turned to Sharif, who laughed and shook his head. The crowd took his cue, clapping loudly and stamping their feet.

Come, come, oh revolution! Move with bravery.

Come, come, for life cannot go on in such wretchedness…

The fatherland is ruined by the elders and the people are lost and homeless.

The poor, the landless, and the shepherds are running in darkness.

—Gul Khan Nasir (1971, poem from Grand)

A harsh and barren landscape is the perfect backdrop on which to project multiple dreams. There is the Pakistani state’s dream of economic transformation, trade over terrorism, access to lucrative markets, and a seat at the regional power table. There is China’s dream of forging a new Silk Road, a global trade route, and a path toward economic dominance. If Indian and American worries are to be believed, China has a second dream too, of tightening its military control across the region.

The dream of economic transformation is shared by at least some Baloch. Mariya, a passionate young woman from Balochistan’s tribal areas, is dedicated to promoting CPEC. Standing at the port, she gesticulated enthusiastically as she explained the great benefits it could bring to her home: a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for her people to be part of the country’s economic future. Even Abdul Malik Baloch, the former nationalist leader, expressed grudging support for the plan, if proper steps are taken to protect Baloch interests.

Yet the incongruities are concrete, and hard to escape. “This is the safest place, not just in Pakistan, but in the world,” Zhang Baozhong, chairman of the China Overseas Ports Holding Company, declared at the seminar. I thought of that as I watched trucks full of police and soldiers close off roads so that our rag-tag group of journalists and researchers could drive through. For the police, this is normal procedure when Chinese officials come to town. In 2004, a car bomb in Gwadar killed three Chinese engineers. More recently, in 2016, two Pakistani coastguards were killed, and in May 2017, gunmen from the Baloch Liberation Army—an armed separatist group—opened fire on construction workers, killing ten.

The poverty in Gwadar is palpable. You can see it in the rundown shops at the side of the road, smell it in the odor of sewage that wafts in through the windows of the armored vehicles foreigners travel in. If the port development could ease poverty, bring revenue and jobs and desperately needed water and electricity to Gwadar, is it such a bad thing?

Perhaps not, but any rapid change of an area, particularly change imposed from the top down, is experienced as a form of structural violence by local inhabitants, no matter what the economic gain might be. Here, there is no guarantee that the intensely poor residents who have made their living for generations as fishermen will be fellow travelers on the journey ordained for Gwadar. The dreams of officials sound surreal, even fantastical. “A five-star hotel will be built here,” they say, on nondescript stretches of barren land. “All this will be unrecognizable.” But that is precisely what the Baloch fear.

One evening, staff at the Pearl Continental set up a meal on the roof terrace. A small water feature ran dry. The tables were set, but food had not yet been served. I walked to the edge of the terrace and looked out at Gwadar town. The electricity was out; there were barely any lights. The hum of the hotel’s generator, powering air conditioners in every room, filled my ears.

At the port, the authorities had laid out a red carpet for us, the visitors. Tacked up on the makeshift display was a map of the planned expansion of the port complex. It depicted a new harbor, forty kilometers away from where fishermen have been based for many years. This was for good reason. The port complex extended right over the area currently known as Gwadar town.