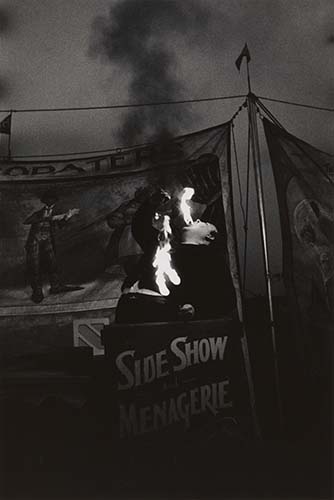

Every great artist has her own creation myth, but the myth of Diane Arbus’s destruction often obscures that of her origins. The current exhibition at the Met Breuer, appropriately titled (and insistently lowercased) “diane arbus: in the beginning,” shifts the focus back to the period preceding Arbus’s meteoric rise in the late 1960s, when her menagerie of drag queens, drifters, nudists, fire-eaters, and unseemly socialites became a public obsession. The show displays work from between 1956 and 1962, a period bookended by two significant technical phases: Arbus’s creative explosion after she quit her post as a fashion photographer for Vogue and her eventual transition from a 35mm camera to a Rolleiflex, which generated the larger square negatives that ultimately made her famous. While a few of her signature Rolleiflex portraits appear throughout the show, most of the prints on view—approximately 100—have never been exhibited before.

The photographs are affixed to a series of vertical panels that are staggered throughout the room without apparent regard for thematic or chronological order. This novel installation technique lends each image a totemic independence and coaxes the museumgoer into contemplative zig-zagging. At the same time, it underscores the striking originality of Arbus’s developing aesthetic and encourages an examination of the context from which it emerged.

The daughter of an upper-class Jewish family who owned the Fifth Avenue department store Russek’s, Diane Nemerov was encouraged to pursue her creative impulses from an early age despite her parents’ general absence from her day-to-day life. Hailed as a talented painter by everyone around her, she played along “without admitting to anyone that I didn’t like to paint or draw at all and I didn’t know what I was doing,” as she later remarked. At age thirteen, the frustrated young painter met an eighteen-year-old boy named Allan Arbus who worked in the advertising department at Russek’s. Five years later, she and Allan were married: his wedding gift to her was a 2¼ x 3¼ Graflex camera.

Not long after her wedding, Arbus enrolled in a class with the already famous photographer Berenice Abbott that outlined the mechanical techniques of using a camera. She went on to teach Allan everything she learned. During Allan’s tour in India during World War II, she took a series of self-portraits documenting her pregnancy and sent them to him along with detailed descriptions of photographs she’d seen in magazines. Yet when he returned to New York and the two of them began pursuing fashion photography as a husband-and-wife team, Diane was relegated to the role of art director while Allan handled the camera. “They were always idea pictures,” Allan recounted of their shoots for Vogue, Seventeen, and Glamour. “[W]e couldn’t work without an idea and ninety per cent of them were Diane’s.”

Arbus had been taking her own pictures during this period, but was often dissatisfied with the results. A 1955 class with Alexey Brodovitch, the pioneering art director at Harper’s Bazaar, was largely unhelpful. But the following year she enrolled in a course taught by Lisette Model, whose quick and candid street photographs had been featured at the Museum of Modern Art. This experience, which came shortly after the termination of Arbus’s photographic partnership with Allan (and three years before their romantic separation), proved to be the turning point of her creative life. With a sudden surge of productivity, she began to make images that hinted at the enchantingly grotesque vision that would become her trademark. It is unclear exactly what prompted this remarkable eruption, though Model’s emphasis on the importance of being true to oneself may have had something to do with it. As she later recalled telling Arbus, “Originality means coming from the source.”

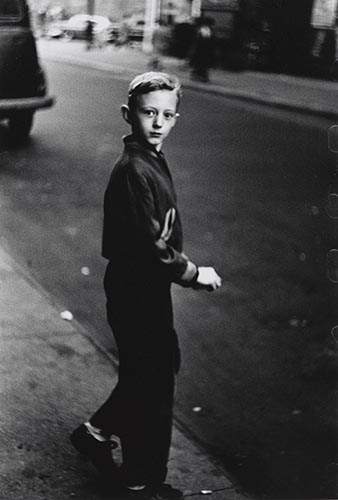

At the Met Breuer, an inadvertent triptych provides a visual metaphor for Arbus’s artistic departure. In one photo, a young boy with neatly combed hair sporting a letterman jacket prepares to step off the curb, his face—surprised yet calm—turned back to the camera, his large eyes wide. In another, a girl holding a white briefcase stands transfixed on the edge of this same small precipice, her round, serious face emerging from beneath a pointed hood. In both of these shots, Arbus uses her subjects to accentuate the almost invisible boundaries of the street; simultaneously, she deploys the vanishing lines of Manhattan’s grid to render it as much a fantastical environment as one of purely menacing remove.

The near empty street in the third photograph, Girl with Schoolbooks Stepping onto the Curb, N.Y.C. 1957, materializes like a stage set, its small, lonely strip of asphalt set between architectural canyons and studded with four ghostly pedestrians. The titular character is our star: mid-stride she toes the threshold with one foot on the curb and one off, biting her lip as she cradles a stack of books in her arms. Perhaps Arbus, the former prep-school student, saw something of herself in this girl wearing a fur-lined coat, knit skirt, and knee-high socks and took the child’s grave expression and determined gait as a sign that she should bound bravely towards her own style.

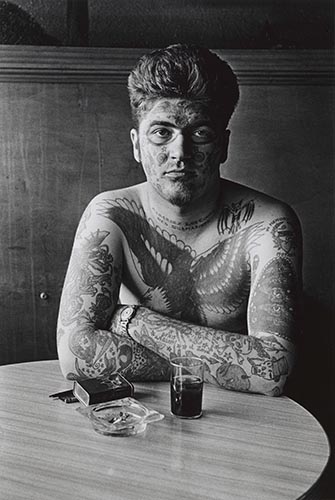

Though far tamer than the work that ultimately made her famous, these three photographs make it clear that Arbus had already developed a proclivity for elevating the ephemeral and everyday. In addition to straddling the territories of curb and street, the schoolgirl seems eager to cross over from reality into the world of imagination, represented by the books she carries. This sense of imaginative transit becomes even more powerful if we consider the literary environment from which Arbus emerged. While her older brother Howard Nemerov eventually became a celebrated poet, Arbus was a voracious reader as well, and along with works by Schopenhauer and Kierkegaard, she had an ongoing relationship with Robert Graves’ compendium of Greek mythology and Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Indeed, it is hard to look at an image like her 1961 portrait of the impossibly tattooed Jack Dracula and not wonder what he looked like before his transformation.

Accordingly, it comes as a bit of a surprise to see that many of Arbus’s early images were completely devoid of the human form. In one, she peers into an empty snack bar where two chairs wait expectantly alongside a table adorned with a discarded teacup, the only sign of recent activity. Another picture, taken in a darkened arcade, features a device called a Mood Meter Machine; glowing faintly, its emotion-sensing joystick seemingly just pulled by Arbus, the machine has decided upon “Tender.” One realizes that as Arbus set out to track down the world’s oddities, she began with what was readily accessible to her, haunting public spaces like wax museums, movie theaters, and barber shops. Only over time did she develop the boldness, cunning, and charisma that characterize the intimate portraits and portrayals for which she is best known.

Several photographs made in movie theaters provide a link between these “un-peopled” scenes and Arbus’s mature work. A few of them are stills of screens themselves, so even when they show individuals they are representations of representations rather than portraits. From a man being choked to a woman who has been gruesomely blinded, many of these movie stills possess a healthy dose of the macabre, a mood Arbus never shied away from. They illustrate how bizarre popular depictions of humanity can be, while actively participating in distortion themselves.

Indeed, whether documenting a wax museum recreation of a murder scene or a regal Fifth Avenue woman in a fleeting moment of anguish, Arbus reveled in the failures of representation, reminding viewers of how often they prefer simulacra to actuality. Early on, Arbus found that the thin veneer we use to conceal society’s fault lines (as well as our own) was surprisingly easy to peel back. Sometimes her photos expose this collective inclination towards fraud, and sometimes they embrace it themselves, intentionally misleading us via their alleged recording of photographic truth.

Arbus’s tendency to play with reality is inextricable from her attraction to the bizarre since in such instances reality itself seems to have initiated the process of distortion. Her early shots taken at carnivals, circuses, and impromptu street festivals illustrate her developing eye for all things outlandish. We see a shabby, squat man biting at the breast of a larger, equally frumpy female friend; a man called the Human Pincushion stands before us nonchalantly, four pins protruding from his half-turned, unperturbed face; an arguing couple scurries away from the Coney Island boardwalk, where they perhaps gawked at the carnival misfits they have now come to resemble.

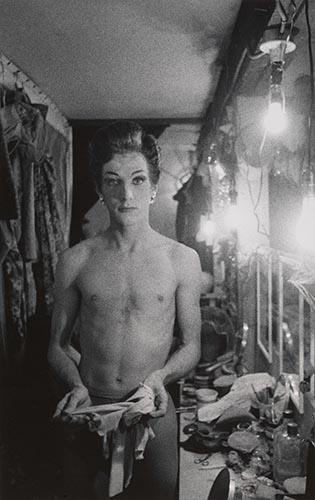

In one of Arbus’s photographs taken backstage at a nightclub, a bare-chested female impersonator with a porcelain face and immaculately coifed hair fiddles with a pair of elbow-length satin gloves in front of a table littered with trash, makeup, and pill bottles. The performer’s unwavering gaze simmers before Arbus’s lens. Here, as elsewhere, the persistence of her camera somehow expresses both detachment and respectful curiosity, a provocative combination that set her work apart from her peers.

A number of writers, most notably Susan Sontag, have claimed that Arbus took her inclinations toward distortion too far—that in setting out to create fascinating or grotesque images, she disrupted the delicate balance between empathy and remove. This allegation may have something to do with the commonly crude understanding of Arbus’s subjects (always labeled “freaks”) as well as with the widespread inability to differentiate between Arbus and her work. Her lifelong struggles with depression and anxiety—compounded, after her divorce, by the pressures of supporting two children—and her eventual suicide have long allowed viewers to liken her misfortunes to those of the people she photographed.

But to do so is to disregard Arbus’s capacity for artistic detachment as well as the deliberateness with which she chose her material. It also stems from confusion about Arbus’s methods. How, we wonder, did this slight, neurotic bourgeois-expatriate coax such evocative images out of wiry teenagers, female impersonators, and members of motorcycle gangs? Arbus’s late-onset rebellion against her constricted origins grew out of her urge for adventure, a hunger that sent her into environments vastly different from her Park Avenue upbringing. And she brought an instrument of transformation with her; for Arbus, there was “a kind of magic power thing about the camera.” Arbus’s adoption of the Rolleiflex especially aided her photographic sorcery—with the camera at waist level, looking down into the viewfinder, she could engage with her subject before clicking the shutter in ways that were not possible with a camera held up to her face. This approach helped her to tease out hidden elements of people’s personalities or evoke connections to unlived pasts and unseen places, making fantasy as palpable as reality.

This ability of hers is often confused with voyeurism, but there was nothing safe or distanced about Arbus’s position relative to her subjects. She relentlessly put herself in uncomfortable environments, and proximity brought intensity to her images. Arbus always sought to increase that intensity and up the ante on discomfort. In her famous image of a boy holding a hand grenade (on display at the Met Breuer), every element of the rail-thin boy’s appearance is disquieting: his ghoulishly contorted face, his knobby knees, the way his empty left hand spastically clutches at a second phantom grenade, even the fact that the left strap of his overalls has slipped off his shoulder.

But a glance at Arbus’s contact sheet reveals that this celebrated exposure is by far the most unsettling of several similar shots: in all the others, the boy appears as a gangly, smiling child with a knack for playacting. It calls to mind the way Stanley Kubrick persuaded George C. Scott to deliver one last exaggerated take for his scenes on the set of Dr. Strangelove, only to use all of those over-the-top shots in the movie’s final cut. Maybe this sort of manipulation was what Sontag was objecting to in Arbus’s work. But knowing the context of Child with Toy Hand Grenade in Central Park only increases our wonder at Arbus’s ability to conjure this instant, fleeting yet everlasting.

Arbus was aware that any moment in an individual’s life could become legend if it contained enough intensity. Like Ovid, she knew that we are all most interesting during the brief junctures in which we transform into our true selves, whether it be as a tattooed tough or a Lady Who Appears to Be a Gentleman (as one of the photos is titled). In the Metamorphoses, everyone is a shape-shifter, whether turning into a lizard, deer, owl, or flower. What these transfigurations have in common is that they are all triggered by a passion so severe it verges on the grotesque. Consider Apollo’s attempted rape of Daphne, whose body adopts the figure of a sprouting laurel tree. In other cases, the resulting form becomes just as monstrous as the original: the hunter Actaeon is torn apart by his own hounds after being changed into a stag by the goddess Diana. Arbus’s later work seems intent on capturing the same kind of passionate transformation, though on a more internal or emotional level.

Over the course of the show, it is Arbus’s ability to glimpse these inward transformations that we see, as it develops. This skill harkens back to another character depicted by Arbus’s cherished Ovid: the gender-shifting prophet Tiresias. After being blinded by Juno for his impiety, Tiresias is told that “that same blow has opened your inner eye, like a nightscope.” During the period that this exhibition covers, it seems that Diane Arbus’s inner eye was opened—permitting her to see beyond the actual into the very lives of her subjects, completing the transformation that led to her mature work, and allowing us to become momentary seers alongside her.