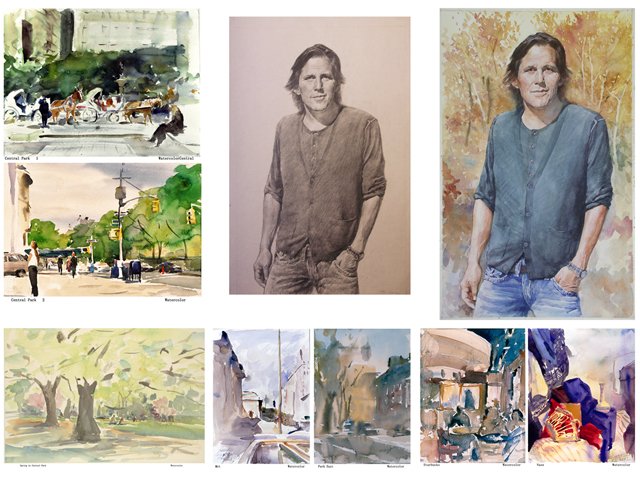

Weiqing Yuan asks his students to call him Wei. He’s a large man who shows his teeth and tilts his head back when he laughs, which he does often, especially after telling a sad story. When I took his watercolor class at the National Academy, he gave no assignments. There was no model. He simply sat beside each student and asked us what we wanted to paint.

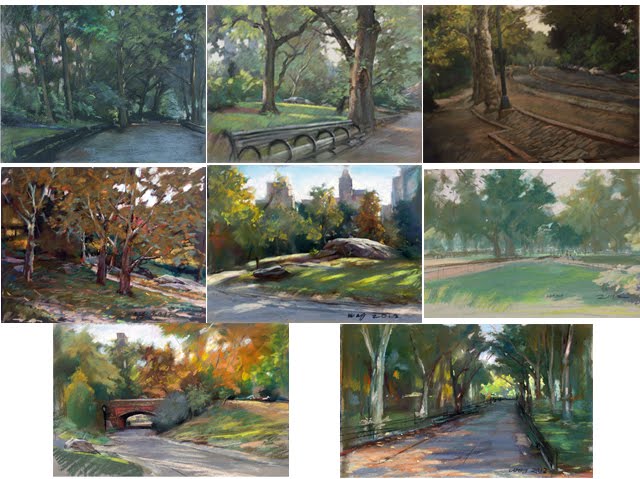

I didn’t know what I wanted to paint, just that I hoped to bury my anxiety under phthalo blue and cadmium red. Wei perched on the plastic stool beside me and asked about my life. I’d just moved back to New York and was living in my grandmother’s apartment. I stared into the jam jar I’d filled with water and told Wei that I’d written a novel about a Japanese would-be artist in 1970s New York. I was waiting to hear back from agents.

From then on, and probably to encourage me, he offered flashes of his own artistic trajectory. Wei is an art teacher, an ex-professor, and an artist with gallery shows. But his first job as an immigrant artist in America involved spending long days on street corners drawing portraits. Real or caricatured, he made whatever the customer ordered. He set up on the corner of Forty-fourth Street and Broadway, the same corner that Ai Wei Wei used to work when he was a college dropout in the late eighties and early nineties. “We never met, not even once. Similar shape, same age. He’s famous, I’m not.” When I heard this, I wondered, How many people unknowingly own Ai Wei Wei originals framed on their living room walls?

After my novel about a Japanese-American artist was published, I fell into many conversations about art and artists. There are stereotypes about the artist’s journey, but there are so many ways artists fight to survive. I found myself retelling Wei’s stories. But I worried I was muddling them in the telling. It also occurred to me how lucky I was to be given a peek of the world of these hardworking artists. I wanted to go back to learn more.

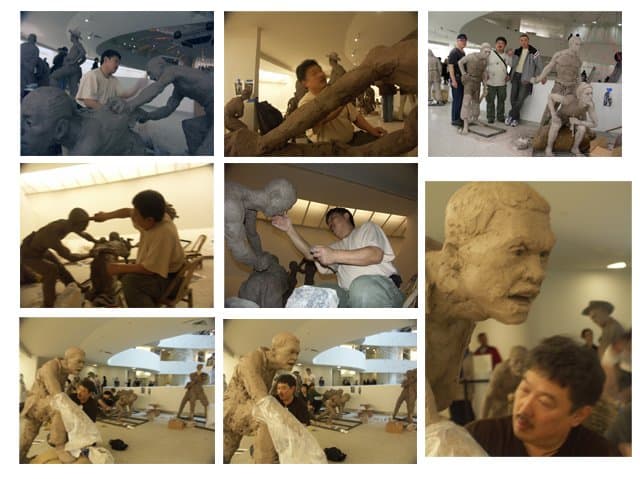

Wei looked the same as the last time I saw him. Close-cut hair; a small, dark mustache; earbuds dangling from a pocket in his hoody; and a quick smile. He gave me a hug that smelled faintly of turpentine and gestured that we should go inside the sculpture room.

Wei came to New York in 1996. In China, he was a professor at the Shandong College of Arts. Like many Chinese people who left in the nineties, he doesn’t talk about why. His first job in New York was in a clothing factory for five dollars an hour. After he discovered that the boss was scamming workers out of their pay, he was let go.

“A guy told me, ‘If you go to Times Square, you find artists working there. If you’re an artist, you might try that.’ I couldn’t find Times Square. I thought it was a square. I [went] back and forth. I couldn’t find a square. Where is the square?”

Wei laughed at his younger self and put a hand on his forehead to mime searching.

“I found someone. This is not like an artist, I thought. This is terrible. I was a teacher more than ten years in China. I had a few students, very famous. You know the Invisible Man? He was my student in the college.”

He was referring to Liu Bolin, the Invisible Man who paints himself and his clothes so that he blends in with his backgrounds. He uses this invisibility to draw attention to issues from labor rights to harmful chemicals in foods. But even in his most successful camouflage, Bolin is more visible than the artists who sit on street corners offering their services to every passerby. Bolin’s TED talk has been viewed over one million times. Wei shakes his head as he tells this story. He wondered how it could be that he, who’d been a professor to such an artist, has ended up working on the streets? In the beginning, he refused tips out of politeness, but later decided to accept them.

“I trained as a Confucian, but you can’t survive like that here.” He found out that it was better not to speak good English, otherwise “Americans won’t pay you, because you’ve lost some kind of charm. You want to learn English? You’ll be punished.”

Eventually, he got a teaching job in New York, but it doesn’t always pay the bills. And so, when necessary, he rejoins the ranks of the street artists. As a young man, he’d been annoyed by the lack of respect. He’d been confused that professors like himself were pushed to work on the street. He’s calmer about it now. “You work on the street, you work for some galleries, you work for the schools, you meet the same people. Maybe you don’t really like some of them, but you have to compromise. I understand that.” I asked if the customers were largely New Yorkers or tourists. He shrugged and said they were a mix of both. He didn’t seem all that interested in his clientele. When he spoke about the other artists, though, he became animated.

“I have two friends—one was a professor. Another one was a student. They fight each other.” The professor was president of the Art Society of Anhui province. It was a good government position. But he was an adherent of Falun Gong, a spiritual movement that the People’s Republic of China has deemed antiscientific and anticommunist. So now he is stuck working the streets of a foreign country next to his former student.

“In Asia, you’re not supposed to fight your teacher, but for five dollars…” Wei shrugged. “They hate each other. Usually the student makes more money.” I asked if this was because the student had more skill. Wei felt it was more of an attitude problem. Customers wanted their artists to be humble. “With amateurs, you don’t have this.” To demonstrate what he meant, Wei arched his back and puffed out his chest, tilting his chin ceiling-ward in the pose of a puffed-up professor. It was the professor’s desire to be respected that made him less successful than the groveling student. Perhaps it is better to have no memory of success.

Cross-cultural tensions existed between the street artists. So many are Chinese that an Albanian artist used to call them “rats” who steal his work. Despite the complaining, Wei admired the man’s skill and would often stop to watch him draw. He’s since passed away, and the rumor amongst the artists is that he died of untreated throat cancer while living in a homeless shelter.

Whatever the rivalry between the artists, the police were a bigger threat. Artists were ticketed for working on street corners. Some were arrested. “During Giuliani’s time, if you’re doing art they give you a ticket. I have friends they locked up more than twelve hours. Police students practicing just pick artists up.” His guess was that these beginner policemen were too scared to pick up “real” criminals.

The one time that Wei went to court, the judge dismissed the charges. Art is a form of free speech, but to lose a morning’s earnings was a punishment in and of itself. To avoid losing those hours in court, the artists found a new way of hiding. They each took on the same name: Ivan. “We picked up the name because Russians seem tougher than us. If the police officer gives us a ticket, we just sign—Ivan. Ivan Drievitch.” Wei rolled the “r” in Drievitch. His whole body shook with laughter at the memory of signing his name that way.

“One guy, last year, came from Norway and said, ‘Many years ago, an artist did my portrait. Very beautiful. I want this artist to do my portrait again. Can you find him for me?’” He said the artist’s name was Ivan. All they could tell him was, “Everybody is named Ivan here.” The Norwegian never found his artist.

Today, there are designated spots where the artists can work. Beyond these perimeters, an artist can still be arrested and summoned to court. When I asked what the future holds for street artists, he paused, and then said he thought it would be harder for all artists under the new administration. We sighed.

As we were wrapping up, he offered some orange juice that he brought in for his sculpture class. I’m not a big juice drinker, but I took the plastic cup and drank it.

Wei asked if I’m still painting. He told me I’ve got to keep going. He made a fist, and said, “You can do it.” I wasn’t quite sure what the it was. Our lives are very distant. But the generosity of this statement struck me. We often think of artists as self-involved. But Wei is one of the most giving people I know. As I walked past the street artists, I thought about the many Ivans.

Long ago, as a school child, I stared at Hans Holbein’s picture of Henry VIII. In the picture, Henry stands tall in a bronze doublet. My teacher said that Henry was much fatter, that he was plagued by warts and gout and boils. The man in the picture was a hero and the man in life was a glutton. What will future art historians make of the flattering pictures, the smiles, and the thick eyelashes the street portraitists give us? What will those historians say we were really like?