It should not be necessary to argue at any length that the slogan “Make It New” is the most durably useful of all modernist expressions of the value of novelty. In certain accounts, such as Gay’s Modernism: The Lure of Heresy, these three words are assumed to sum up most of what modernism stands for: “In short, modernists considered Ezra Pound’s famous injunction, ‘Make It New!,’ a professional, almost a sacred obligation.” Scholars as eminent and yet as utterly different from one another as Richard Rorty, Frank Lentricchia, Jackson Lears, Fredric Jameson, and David Damrosch have used this phrase to make various points about modern life, art, or literature. Some of these citations are vague and atmospheric, even anonymous, as the slogan is often used without specific reference to Pound. But this is perhaps an additional tribute to his influence, as the slogan has become so ubiquitous as to have lost its trademark status, like Kleenex or the Xerox copy.

The crucial fact to begin with is that the phrase is not originally Pound’s at all. The source is a historical anecdote concerning Ch’eng T’ang (Tching-thang, Tching Tang), first king of the Shang dynasty (1766–1753 BC), who was said to have had a washbasin inscribed with this inspirational slogan.

The actual genealogy of the phrase “Make It New” has been established by Pound scholars and is well known to those among them who specialize in Pound’s relation to China, but it is so often misdated and for that matter misquoted (tagged with a spurious exclamation mark) that its genesis is worth recounting in some detail. The crucial fact to begin with is that the phrase is not originally Pound’s at all. The source is a historical anecdote concerning Ch’eng T’ang (Tching-thang, Tching Tang), first king of the Shang dynasty (1766–1753 BC), who was said to have had a washbasin inscribed with this inspirational slogan. According to the sinologist James Legge, it is not a commonly told anecdote, but Pound was fortunate enough to have found it in two sources: the Da Xue (Ta Hio), first of the four books of Confucian moral philosophy, and the T’ung-Chien Kang-Mu, a classic digest and revision of an even older classic Chinese history. That Pound coincidentally found the same uncommon anecdote in two different places may be explained by the fact that both texts were prepared by the neo-Confucian scholar Chu Hsi (1130–1200 AD), who has perhaps the best claim as true originator of the slogan Make It New.

Pound first became interested in the Confucian texts in October 1913, at about the time he received from the widow of the art historian Ernest Fenollosa the materials that would lead to Cathay and The Chinese Written Character as a Medium for Poetry. Inspired by the poet Allen Upward, who had published some translations from the Analects in the New Freewoman, Pound started reading Confucius, first in Upward’s English selection and then in more complete versions in French. Sometime in the later 1920s, he began preparing his own translation of the Da Xue (Ta Hio), a text that Legge had called The Great Learning. It seems clear that at least toward the end of his work on this text, Pound had a copy of Legge’s English version, almost certainly in an edition that included the Chinese original. For reasons of his own, however, he chose to work primarily from the French version he had owned for some time: M. G. Pauthier, Confucius et Mencius: Les quatres livres de philosophie morale et politique de la Chine, published in Paris in various editions beginning in the 1850s.

Pound’s translation of the Da Xue, entitled Ta Hio: The Great Learning, Newly Rendered into the American Language, was published by Glenn Hughes as a University of Washington Bookstore Chapbook in 1928. As is explained in an opening note to this translation, the Da Xue is the first of the traditional Four Books of Confucian wisdom, but only the very first part of the Da Xue itself is attributed to Confucius (only forty-six characters in the original, Pound adds in an interpolated comment). The bulk of the work comprises commentary and annotations by a disciple that Pound calls, after Pauthier’s French, Tsheng-tseu. It is in these annotations, further refined themselves by the subsequent editing of Chu Hsi, that the first published version of Make It New is to be found.

The subject of the Da Xue (Ta Hio) at this point is good government, which is to be achieved by renewing the virtues of the sovereign and enlightening the people. As an illustrative anecdote, Tseng Tze (Tsheng-tseu), the commentator, notes the story of King Ch’eng T’ang (Tching-thang), who was said to have a bathtub or washbasin with the following inscription engraved on it:

Renouvelle-toi complétement chaque jour; fais-le de nouveau, encore de nouveau, et toujours de nouveau. (Pauthier’s French)

If you can one day renovate yourself, do so from day to day. Yea, let there be daily renovation. (Legge’s English)

Renovate, dod gast you, renovate! (Pound’s American)

Pound’s version has at least the virtue of brevity, but he spoils the effect somewhat by adding a long footnote, which actually translates the French again: “Pauthier with greater elegance gives in his French the equivalent to: ‘Renew thyself daily, utterly, make it new, and again new, make it new.’” “Make it new” actually seems a fairly willful translation of “fais-le de nouveau,” which might just as easily be rendered “do it again.” Had Pound translated it so, the whole history of modernist scholarship would presumably have been quite different. Moreover, “make it new” seems to remove the reflexive sense present in all these translations and thus to turn the aphorism away from its obvious topic of self-renovation. But Pound is clearly a little transfixed by the italicized nouveau, attracted to it, and oblivious to the possibility that its force might not be augmented but rather diluted by repetition. In any case, his footnote also shows another influence when it refers to a second translator, who testifies that “the character occurs five times during this passage.” In his excitement, Pound neglects to tell us which character, but the translator he is referring to here is Legge, who says in his commentary on this passage that “the character ‘new,’ ‘to renovate,’ occurs five times.” Additionally, Pound’s footnote goes on to make it clear that he has an edition of Legge with the Chinese, for he maintains that “the pictures (verse 1) are: sun renew sun sun renew (like a tree-shoot) again sun renew.” In other words, Pound has identified the Chinese character that Legge translates as “new,” “to renovate,” and has allowed it to drive his footnoted retranslation. When Pound’s Ta Hio was republished by Stanley Nott in 1936, it included this character, xin (hsin), in the place of pride on the title page.

It is actually this character, sometimes with its companion, jih, the character that Pound took to represent the sun, that is included sporadically in his later work. Usually, the Chinese is shadowed somewhere in the text by an English equivalent, though Pound is not always very careful to link the two securely together. But he never publishes the English without the Chinese, which is to say that he always represents his phrase as a translation of the motto of an ancient Chinese nobleman. In short, Pound does not offer Make It New as his own words or in his own voice. It is a historical artifact of some interest, to be sure, but it is not to be understood out of context, as if it were being delivered by Pound himself to the present-day reader of Pound’s own text. One of the main reasons to keep this context in mind, even now, is that it restores the full complexity of Make It New, which is in fact a dense palimpsest of historical ideas about the new.

Even the oldest and most basic layer, that of the original Chinese, is not simple or undifferentiated, since the Da Xue (Ta Hio) as Pound came to it was the product of neo-Confucian interpretation of a text compiled from various sources. But Pound clearly felt that he had found in this ancient text a model of novelty that was itself ancient and even foundational. The Chinese indicates, as he says in the relevant footnote to his first translation of the Da Xue, “daily organic vegetable and orderly renewal.” Thus his notion that the character for “renew” is to be glossed with the modification “like a tree shoot.” Regardless of whether this is actually to be found in the Chinese, it does correspond to the most ancient definitions of novelty available in Europe, which were based on the obvious models in nature. One of the innumerable possible examples of this conventional notion is to be found in Ovid: “Ever inventive nature continuously produces one shape from another. Nothing in the entire universe ever perishes, believe me, but things vary and adopt a new form.”

This very ancient version of novelty, if it is in the Chinese text at all, does not come to Pound directly but as mediated through the interpretations of the first English translation he turned to, that of James Legge. In helping Pound to discover an organic model of novelty in his text, Legge also layers over that another and slightly more recent one. A Christian missionary as well as a scholar of Chinese, Legge believed, almost as an article of faith, that the wisdom to be found in the Confucian classics could be related to that in the Christian scriptures. The Bible in fact became his model for the organization and interpretation of what were called the Five Classics and the Four Books, which Legge saw related to one another as Old to New Testament. It is not at all odd, then, that his version of the Da Xue (Ta Hio) should often sound a lot like the King James Bible. His version of Ch’eng T’ang’s bathtub inscription, which reads, “If you can one day renovate yourself, do so from day to day. Yea, let there be daily renovation,” seems to have been based at least in part on 2 Corinthians 4:16: “Though our outward man perish, yet the inward man is renewed day by day.” In fact, Pound’s own formula, seemingly so simple and so modern, is constantly anticipated in the New Testament, especially Revelation 21:5, which promises, “Behold, I make all things new.”

Though the basic concepts of renewal, regeneration, and rebirth all imply a return to some earlier state, Christian theologians defined these terms so that they could also mean return to something better than what had existed before.

Pound’s own Presbyterian background may be at work here, as well as the influence of Legge’s translation. In any case, what happens is that a new layer is added to the base model of organic change occasioned by the Chinese original. The model on this layer, Christian rebirth, is based on that of organic change but brings with it certain significant differences. As the medievalist Gerhart Ladner explains it, when Paul uses terms such as neos to describe the “new man” to be achieved in Christian conversion, he not only introduces a significant religious concept but also changes the meaning of the term new. What had ordinarily been used in a merely temporal sense, often with a pejorative connotation, now acquires a meliorative and redemptive significance. Though the basic concepts of renewal, regeneration, and rebirth all imply a return to some earlier state, Christian theologians defined these terms so that they could also mean return to something better than what had existed before. Thus humankind need not merely return to the state of nature, even in its perfect form in Eden, but to a resemblance to the creator even truer and closer than that of Adam. Thus Paul says in 2 Corinthians, “If any man be in Christ, he is a new creature: old things are passed away; behold, all things are become new,” implying that the new does not just return to but also surpasses and supplants the old.

The fact that Pound left the Presbyterian Church far behind as he moved through the avant-garde movements of Europe does not necessarily mean that the echoes of the New Testament in Make It New are merely verbal. His own most constant model of change, that of renaissance, begins with and is based on the two earlier versions of novelty. The dependence of this model on that of organic change is obvious in the term itself. When Pound’s favorite Renaissance theorist, Jacob Burckhardt, speaks of “the resuscitation of antiquity,” he brings out a latent link between the notion of rebirth and that of resurrection. As Ladner puts it, the metaphorical meaning of renasci is closely linked to horticulture, to the new growth that sprouts from the act of pruning, a meaning that is expanded in Christian times to relate to spiritual rebirth, “with connotations which could range all the way from vegetative to cosmological renewal.” Consequently, when Pound chooses Make It New as the title for his collection of essays on the troubadours, Elizabethan classicists, and translators of Greek, he is being consistent with the tradition of cultural rediscovery and rebirth exemplified by the Italian Renaissance. In the later cantos, where he tends to attach the Chinese characters so closely to quotations from and references to Ocellus that it is easy to imagine that this ancient Greek philosopher is actually a Confucian sage, Pound is re-imagining the Da Xue (Ta Hio) as if it were the first in a series of spiritual bursts of light, flashing again and again as ancient learning is revived by one renaissance after another.

The form, then, of Make It New is recombinant, as it comes to signify a whole anthology of Pound’s efforts and interests. As he says himself, major poets “heap together and arrange and harmonize the results of many men’s labour.”

Even the more sinister applications that Pound developed for the motto have a significant relationship to this history. In 1935, Stanley Nott published Jefferson and/or Mussolini, one of whose many subtitles was Fascism as I Have Seen It. In this text, Pound summarizes the Da Xue (Ta Hio) in two pages, including again the Chinese characters. In this case, he translates the characters as “Make it new, make it new as the young grass shoot.” But he also includes a footnote, which claims that the first ideogram, xin (hsin) or “renew,” “shows the fascist axe for the clearing away of rubbish.” This vivid pictographic interpretation is derived from a Chinese dictionary, compiled by the Protestant missionary Robert Morrison, that Pound had owned since 1915. Morrison gave Pound the idea that the right-hand side of the xin (hsin) character represented a “hatchet,” shown hacking away at the wood supposedly represented on the left. It was Pound’s own inventiveness that associated the ancient Chinese hatchet with the Fascist axe and his own increasingly vindictive hatred of complications that provided the rubbish, which is not present in the Chinese original.

Pound had in fact taken his slogan quite a way from its Chinese origins, which emphasized the necessity of self-renewal, not the forced renewal of others, and he had removed it even farther from any association with avant-garde agitation. The renovation demanded by the slogan was now the dictator Benito Mussolini’s “rivoluzione continua,” and the “rubbish” to be cleared away was not excess verbiage but a whole people. What appears to be a paradox in the Fascist slogan of “rivoluzione continua” is in fact the remains of the earliest meaning of revolution preserved within a modern travesty of it. At this time, Pound begins to show particular interest in the “young grass shoot” supposedly represented in the Da Xue (Ta Hio) because it resonated with parts of the Italian Fascist program, but he also asserts and exaggerates its presence because it ties Mussolini’s drastic plans for Italy back to an apparently natural process of destruction and renewal. The “continual” or constant nature of the revolution thus appears as part of the older meaning of the term, in which revolution merely meant a complete turn in the course of events.

With this history, running from ancient China to Fascist Italy and back in place, Make It New can be seen to imply a complete history of the concept of novelty. Of course, the explicit emphasis of this history is on models of recurrence, from organic renewal to Fascist revolution, and there is no doubt that Pound felt the appeal of the total transformation that such models promise. But it is also hard to miss the fact that Pound’s actual practice in his successive repetitions of this slogan is one of quotation and combination. Pound habitually worked by arranging and re-arranging certain bits of knowledge that had been canonized within his own idiosyncratic system, and the ancient Chinese saying is but one of many nodes in this system, attracting to itself over the years bits of Mussolini and bits of Neoplatonism and even bits of modern anthropology. The form, then, of Make It New is recombinant, as it comes to signify a whole anthology of Pound’s efforts and interests. As he says himself in “The Serious Artist,” major poets “heap together and arrange and harmonize the results of many men’s labour. This very faculty for amalgamation is a part of their genius.”

The most significant fact to emerge from this history, though, is also the most obvious: Make It New was not itself new, nor was it ever meant to be. Given the nature of the novelty implied by the slogan, it is appropriate that it is itself the result of historical recycling. This was a fact that Pound himself always tried to keep in the forefront by using the original Chinese characters and letting his own translation tag along as a perpetual footnote. The complex nature of the new—its debt, even as revolution, to the past, and the way in which new works are often just recombinations of traditional elements—is not just confessed by this practice but insisted on. This is what makes the slogan exemplary of the larger modernist project, that by insisting on the new it brings to the surface all the latent difficulties in what seems such a simple and simplifying concept. It was only later, as critics and scholars tended to the endgame of modernism, that the new was simplified again, a process in which Make It New was to play a crucial role.

The Making of Make It New

Make It New is now such common shorthand for modernist novelty that it is easy to assume that it was always so. Yet these three words did not appear in Pound’s work, it should be remembered, until 1928, well after the appearance of the major works of modernist art and literature, and the words did not become a slogan until some considerable time after that. Just how utterly obscure the phrase remained even in the middle 1930s is evident in the reaction at Faber when Pound proposed it as the title for a collection of essays. Eliot informed him that Faber was not “altogether happy about your new title make it noo we may have missed subtle literary allusion but if we do I reckon genl public will also.” The general public did miss the allusion and, in fact, the larger significance of Pound’s reference, which quite escaped the reviewers when the collection appeared. Of thirteen contemporary reviews of Make It New consulted for this study, only two so much as mention the title, and both make it the target of sarcastic comment.

In the course of this remarkably brief transformation, Pound’s three-word phrase loses its ancient Chinese context, its debt to the devotional program of Legge, and its involvement in Mussolini’s Fascism.

In fact, it seems safe to say that no particular significance was attached to Make It New until 1950, when Hugh Kenner called attention to its reappearance in a new translation that Pound had prepared of the Da Xue (Ta Hio), which he now called The Great Digest. When Kenner notices “the ‘Make It New’ injunction in the Great Digest,” not only does he pick this phrase out of the welter of Pound’s prose for the first time, but he also nominates it for the role it was later to play. Even here, though, Kenner refers to the “injunction” not as Pound’s but as belonging to the Great Digest; and when he glosses the injunction, he links it not to imagism or free verse or insurrectionary art in general but to “Pound’s translating activities.” Thus the emphasis is not on novelty at all but rather on “the sense of historical recurrence that informs the Cantos.” Even at this stage, though it had at last been recognized as an “injunction” of sorts, Make It New had not acquired either the meaning or the status that now seems inevitable.

Only six years later, the literary critic Philip Rahv refers in the Kenyon Review to “the well-known avant-garde principle of ‘make it new.’” Somehow, in the course of these few years, the quotation that had been obscure even to Eliot in 1934 and that had meant “recurrence” to Kenner in 1950 has become the all-purpose label for modernist novelty. In the course of the later 1950s and the early 1960s, writers for the literary quarterlies would make it into a catchphrase. The literary critic and literary theorist Northrop Frye, for example, writing in the Hudson Review in 1957, associated the “anti-‘poetic’ quality in Stevens” with “his determination to make it new, in Pound’s phrase.” The literary scholar Roy Harvey Pearce, writing in the same journal two years later, said that any American attempting an epic poem “would indeed have, in Pound’s phrase, to make it new.” By 1966, the literary critic Marvin Mudrick had turned the phrase into a single word: “make-it-new.” Writing in these years and in these journals, literary scholars such as Roy Harvey Pearce and Richard Ellmann established a dogmatic belief in “Pound’s determination to make it new,” and by way of Pound an association of modernism with novelty per se.

In the course of this remarkably brief transformation, Pound’s three-word phrase loses its ancient Chinese context, its debt to the devotional program of Legge, and its involvement in Mussolini’s Fascism. The bibliographical facts of its appearance in Pound’s work are so thoroughly obscured that it becomes possible for scholars such as Peter Gay and Alfred Appel to misplace it to 1914, where it can seem influential and even foundational instead of obscure. In the process, the role of novelty in the development of aesthetic modernism is distorted, and the nature of novelty itself is simplified. The vast array of different positions that can be identified among the practitioners of modern art and literature shrinks to the size of a simple, three-word slogan, and the complex history of novelty is subtracted even from that, so that modernism loses a crucial part of the debt to tradition that it owes, paradoxically, through its devotion to the new.

One of the reasons this happens in this particular way, it seems certain, is the sheer passage of time and the requirement of retrospective accounts of modernism for a quick and easy version of its defining characteristic. But this also happens, it is interesting to note, at just the time Kuhn was publishing The Structure of Scientific Revolutions and Danto was using his ideas in an effort to assimilate the Pop art of Andy Warhol. Pound’s translated phrase achieves its canonization as a modernist slogan at this crucial moment, it seems, because novelty is being redefined under a certain amount of pressure. The aging and presumptive passing of modernism lead to a crisis in the concept of novelty that is felt and fought out at just this time.

Reprinted with permission from Novelty: A History of the New, by Michael North, to be published in October by the University of Chicago Press. © 2013 The University of Chicago. All rights reserved.

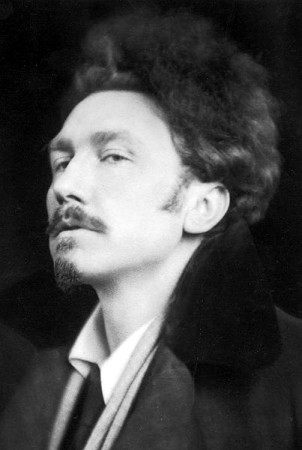

Michael North is professor of English at the University of California, Los Angeles and the author of several books, including The Dialect of Modernism, Reading 1922, and Camera Works.