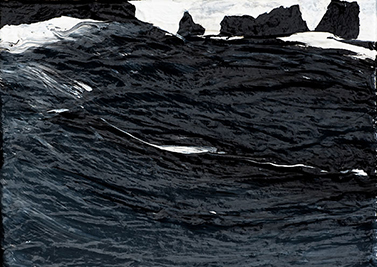

We’re named the Kings, and we’re the closest thing to royalty on Loosewood Island. The story goes that when the first of the Kings, Brumfitt Kings, the painter, came to Loosewood Island near on three hundred years ago, the waters were so thick with lobster that Brumfitt only had to sail half of the way from Ireland: he walked the rest of the way, the lobsters making a road with their backs. He was like Jesus walking on the water, except there was no bread to be found anywhere. Lobster there was plenty of. In 1720, the waters were crawling with them in sizes that no man today has seen. To catch his first lobster, Brumfitt didn’t bother with boats or traps or anything more complicated than simply wading into the water at low tide and gaffing a lobster ten or twenty pounds or more. He caught lobsters five feet long. When I was young I heard old men down at the harbor and in the diner talking about how when their grandfathers were boys they saw lobster claws nailed to the sides of boathouses, claws big enough to crush a man’s head. The lobsters are smaller now, but they’ve done well for the Kings. Back when I was a girl in school, we were told about how lobsters used to be cheap trash fish for filling bellies, but it’s hard to believe. Daddy and I both drop pots and haul lines and he’s raised all three of us girls on the money the lobsters bring in. Raised us well enough, too. Carly, the youngest, teaching in Portland for the last few years after Daddy put her through Colby College, hard cash that could have gone to buy a third boat. Rena, the middle daughter, like so many of us living on an island that is claimed by both the U.S. and Canada, taking some schooling on both sides of the border—she started nursing school at Dalhousie University, in Halifax, and finished up as an accountant at the University at Albany, SUNY—and now married and back on the island, running the fish shop and managing our books with her husband, Tucker, trained as an architect but working as Daddy’s sternman. And me. The oldest daughter. I went to college, too, and I studied art, but as much as I love to paint, I never wanted to paint anything other than Loosewood Island, never wanted to do anything other than live here and walk the same beaches and paths, paint the same famous landscape that Brumfitt Kings painted, and, girl or not, to head to sea to work like Daddy and his daddy before him, and so on and so forth all the way back to Brumfitt Kings, Kings of the ocean, lobster Kings. I have two sisters, but I’m the one who works the ocean with Daddy, Cordelia Kings, heir to the throne.

My own memories start on a boat. I was small enough that Daddy cut me down a rod, I think, though it might even just have been a stick with some twine tied to it. Whichever it was, it did the trick: I went to cast my line and I hooked Daddy’s lower lip with my lure. The metal was speared completely through the flesh. Blood spilled out of Daddy’s mouth, the silver dangle of the lure flashing in the sun. I remember that I cried when he yelled at me, but he says that I’ve got the story wrong, that it was the other way around, that he yelled at me because I cried, and that sounds about right for my father. He can’t remember why it was just me with him out on the boat, what my sisters were doing—“probably at home with your momma, just waiting for your brother to be born”—but he can remember the weather and the low tide time for every day stretching past more than forty years. He says that was why he married Momma, so he’d have somebody to remember things for him, like birthdays. That’s the only way he talks about my mother anymore, as if she were some sort of prank he pulled.

We weren’t out in Daddy’s lobster boat, the Queen Jane. I remember that, too. The boat was small, a skiff or something borrowed, and my feet got wet from water in the bottom. I remember being cold, but there again my father says I’m remembering wrong. It was the beginning of June, he says, the week before Scotty was born, and hot in a way that comes as a surprise any day on Loosewood Island, but particularly that early in the summer. It makes sense that it was June, when the lobsters are busy tucking themselves into rocks and growing new shells. Loosewood Island has its own particularities with the lobstering season, and there’s a moratorium on catching lobsters from June through the middle of August. It’s different in different places, but that’s the calendar we work by. So my father would have just been maintaining traps, fixing up the Queen Jane. Plenty of downtime ahead of him, enough time to take me out fishing.

The hook in his lip turned his words into a bloody mumble, and he gave me a smile that made the lure jiggle.

He cut my line with the knife he always kept clipped to his belt—or to his slickers when he was working—and he told me to quit crying, his voice now soft and calm, the lure hanging bloody from his lip. I put my fishing pole down on the bottom of the boat, snuffled, and wiped at my nose with my sleeve. He worked at the hook for a little, trying to see if he could thread it back out the way it had come, but he had been hooked cleanly, the barb pushing up and all the way through. The fishing line flossed in the soft breeze like a streamer. “You’ve caught yourself a whopper, darling,” he said to me. The hook in his lip turned his words into a bloody mumble, and he gave me a smile that made the lure jiggle in the sun. The spoon of the lure flashed at me. I had a magpie moment, wanting just to grab at the shininess of the metal, but I kept my hands down. He pulled out the tackle box and rooted around in it, calmly and slowly, as if he didn’t have my hook stuck full through him. The blood flowed, drip, drip, dripping down his chin and onto the floor of the boat. It mixed in with the seawater that had been wetting my feet, clouding out, diluted and strange. He took out a pair of pliers and said, “This will serve.”

He pulled his lip gently and nestled the pliers against the hook. For a second I thought he meant to just yank it, ripping out the flesh, and if I hadn’t been so afraid, I would have started crying again. Instead, he used the wire cutters on the pliers to snap through the hook. He moved the lure away and then worked out the small piece of hook that still hung in his lip, holding on to the barbed end with his fingers and drawing the sheared end out of the flesh. As soon as he pulled the metal out, the blood welled up stronger and started to pour down his chin. Still, he was careful to put the lure and the sharp spear of the cut hook into the tackle box so that nobody would accidentally step on it—the same sort of careful consideration of future actions and calamities that served him well as a lobster boat captain—before he pulled off his shirt and wadded it up as a bandage, pressing it against his lip.

“We’d best head in, darling,” he said to me. “I wouldn’t mind getting this cleaned up, see if I need a stitch or two. Besides, it’s getting late enough that your momma will be looking for us. Looking for me, really, to give her a hand with your sisters. And who knows,” he said, giving me a wink, “maybe the baby is on its way.”

That memory, of hooking Daddy, blurs with my memory of meeting my baby brother, but I know they were two separate events. It would have been a week or so after the fishing trip that Scotty came home from the hospital. The thin, ugly stitches knotted on Daddy’s lip were only partly disguised by the growth of his beard. I remember standing on the deck of the Queen Jane and getting my first look at my baby brother. It doesn’t make sense to me now—why wouldn’t Momma have been there with the baby?—but at the time it felt normal to be out on the Queen Jane without Momma, without my sisters. I’m sure there was nobody else on the boat, I’m sure it was just Daddy, my brother, and me.

Daddy sat in the captain’s chair, cradling the baby. Scotty was crying, the sort of mewl that comes from newborns, and I thought, He doesn’t like it here, doesn’t like it on the boat, doesn’t like it on the water. I understood right at that moment that he was just like my sisters: Scotty didn’t belong on the Queen Jane any more than they did. As I had that realization, Daddy scooped me up and into his lap, and I thought, Daddy sees it too. I remember what it felt like to burrow against him, to be looking down at Scotty, the surge of pleasure at the understanding that I thought I shared with Daddy, the belief that I was the one who was meant to be out on the water with him. Daddy was a loving father, but he was certainly not a cuddly one, and to be on his lap was a privilege rarely afforded. I felt like a commoner sitting on the throne.

But as Scotty kept crying, Daddy looked at me and then nodded at Scotty and said, “Here, look at him, Cordelia. This is your brother. Look at him, because he carries with him the weight of our history, the lineage of the Kings family.”

I could also feel something else, could feel with a certainty as loud as Scotty’s increased cries that this was not a boy who was born to rule the sea.

Even though I know that I can’t actually remember the words with such exactitude, that I was only three and a half when Scotty was born, that those words wouldn’t have made any real sense to me at the time, I can still hear every word that Daddy said. “Look at him,” he said. “Look at this little boy, Cordelia, because he is both our past and our future, and there is going to be a day when he takes over the family business, when he is out on the water, when Scotty Kings is going to be the king of Loosewood Island.” He leaned over and kissed me on the head then and asked me if I wanted to hold Scotty. I nodded, but I didn’t really want to hold him. He was just a baby, I thought, small and loud and deserving of nothing, and Daddy had already decided to give him what I knew to be my birthright as the firstborn, girl or not. As much as I could feel Daddy’s arms around me, holding me on his lap and holding Scotty steady, I could also feel something else, could feel with a certainty as loud as Scotty’s increased cries that this was not a boy who was born to rule the sea.

And I remember this, too, though I know it can’t have been real: Daddy standing up, stepping over the edge of the boat, and walking across the water to the shore, with me and Scotty in his arms, walking across the top of the ocean, taking me home to Momma, Rena, and Carly. I remember the way he cradled me, like I was still a baby, even with Scotty in my arms, and I remember that there was part of me that wanted to close my eyes and let it be a dream. Instead of closing my eyes, however, I looked down at Daddy’s feet leaving ripples on the surface of the ocean, and then out to the rocks and the shore of Loosewood Island, as he carried me across the water.

By the time I was twelve I’d started showing breasts, and Momma had been making noises about how the Queen Jane wasn’t a place for me or my sisters to be spending our weekends, that squatting on the deck to pee and hosing it off wasn’t the best training for the kind of girls she was trying to raise. She’d never been warm to the idea of me, Rena, and Carly fishing, but she was always ready with an extra lunch for Scotty to take along. He belonged out there with his daddy, she’d say, because otherwise how would he learn to be a lobsterman?

Despite Momma’s urgings and Daddy’s steady attention, Scotty was always the last one out the door. On a Saturday morning, when I’d already be in my boots and slicker down at the docks, checking the bait, recoiling any lines that I didn’t like the look of, he’d still be sitting at the table, as if his sugared cereal could stand to soak up more milk. Still, come December, when me and my sisters had all been sick for weeks—the cooped-up, crouped-up, coughing crud you can get when you live hard against the ocean’s edge and winter has come to settle itself in for good—even Scotty was eager to get on the boat. School had just taken to vacation for the winter break, and we already had our Christmas tree cut and standing in the living room, trimmed with tinsel and ornaments that Momma unpacked from the same tissue paper-filled boxes every year. Carly and Rena were still hacking, but I’d been clear of sickness for a few days, driving Momma crazy with energy, and Scotty had never taken to coughing, so when the weather broke clean and warm—or what passed for warm in December on Loosewood Island, just above freezing—Daddy bundled the two of us up in our woolens and rain gear, whistled up for the dog, Second, and took us out on the Queen Jane.

If you aren’t familiar with lobster boats, one looks about the same as the other: a high bow forward of the cabin, and back of the cabin, low sides and stern to make it easier for hauling traps. The Queen Jane was no different. It looks like what it is, which is a lobster boat that was bought new in 1952 and handed down from my grandfather to my father, a boat that has seen a lot of weather but that has been taken care of like my daddy’s life depends on it. Which it does.

Daddy had been fishing these traps as pairs, which meant that pulling one trap actually meant pulling two, and he gaffed the first buoy, slapped the warp into the hauler, and let her rip. The traps broke the surface glistening with mud and a decent catch of bugs despite being an off time of year. He pulled the second trap off the rail and put it on deck with the other and then said, “Here, Scotty, come on over. I’ll rebait, but you separate the traps out. I want to put them back in as singles.”

I got to my feet, but Daddy looked at me and shook his head. “I want Scotty to do it, Cordelia. He’s nine. Old enough to start taking over more. He’s a Kings, and he can earn his keep.”

That was all he said, but it felt more like a kick in the gut. It wasn’t just that Daddy wanted Scotty to do it, but that he didn’t want me to do it. I spent as much time on the Queen Jane as I could. Daddy liked to joke that I was the youngest sternman on the island, but the price was right. I could haul a trap, empty it, and rebait it fast enough that I was more of a help than a nuisance, and Daddy never said anything about me being just a girl. I was a Kings through and through, and Daddy knew it. I belonged out on the water. But Daddy never seemed able to see what I could see so clearly about Scotty, which was that my brother wasn’t made for the ocean. Scotty tried, he really did, but only when Daddy was looking. When Daddy asked if Scotty wanted to learn a new knot, to see how to adjust the diesel engine, Scotty always said yes. When we were on board and Daddy called him over, Scotty scrambled like a puppy because he didn’t want to disappoint Daddy, but the truth was that Scotty didn’t want any of it for himself. Left to his own devices, Scotty would have been just as happy to be playing football with his friends or to be back at the house with Momma.

I didn’t say anything, and it was only when the trap was already up on the rail and starting to teeter over that Daddy saw the mistake my brother had made.

I stayed in the relative warmth of the cabin and watched Scotty untie the knots from the paired traps while Daddy rebaited and banded the keepers. And I didn’t say anything when I saw that Scotty had only tied a line to one of the two traps. He struggled with that first trap, getting it up and over the rail, letting it splash into the water. The line played out of the boat as the trap sank. I waited for him to notice that the second trap was naked, that there was no line attached, no buoy, nothing to keep it from disappearing in the depths, but Scotty didn’t notice. Scotty didn’t notice, and I didn’t say anything, and it was only when the trap was already up on the rail and starting to teeter over that Daddy saw the mistake my brother had made.

Daddy lunged for the trap, but it was too late. It fell from the boat, hit the waves, and sank. “Scotty,” Daddy barked. Scotty had already started to realize what had happened, and I saw the way his face went blank, as if by not acknowledging that he’d thrown away a trap it might mean that it hadn’t happened. “You didn’t tie a line… How could you…” Daddy shook his head and pursed his lips. He didn’t say anything more than that, but he didn’t need to. It wasn’t the cost of the trap—we lost gear all the time to weather and accidents—but the way that he’d lost it. Such a stupid thing to do. But then Daddy shook his arms, forced a smile back onto his face, and put his hand on Scotty’s shoulder. “Don’t worry about it, son. Mistakes happen. It’s a good lesson. Always double-check to make sure you’ve got your gear ready to go. It could happen to anybody,” Daddy said.

Except, I wanted to say, it couldn’t. That wasn’t the sort of thing that I would have done, I wanted to say. But I didn’t. I kept quiet even as Daddy moved the Queen Jane to the next spot on his line, even as he pulled the next pair of traps, measured the lobsters, kept one, and threw the rest back. He looked at the two traps and then shook his head. “We’ll throw these ones back in the water and pull the rest of the line. The first two are rebaited, and I’ve got a couple on the backside of the island that will do for the family.” He roughed Scotty’s hair. “Everything else we pull we’ll bring back to land. You kids stack them up and lash them.”

I didn’t bother moving from the cabin. If Daddy didn’t want me to help when we were rebaiting and dropping traps, I didn’t want to help now. Besides, Daddy was watching, so Scotty was acting the good son, was already dragging the traps across the deck. He was being quick and eager, trying to do the right thing, trying to make Daddy forget his mistake. Daddy came back to the wheel and pushed the throttle. He didn’t say anything to me about not helping Scotty, but he gave Second a tap with his boot. The big Newf uncurled himself from under the wheel and walked over to where Scotty was wrestling with the traps and the bounce of the boat over the waves. Second nosed at Scotty and let out a few barks.

Highliners and dubs alike, they keep the ropes neat. The only lobstermen who don’t keep their ropes neat are the dead ones.

It was the sort of thing that happens all of the time. A mistake. There’s the weather, there’s the waves, there’s the lobsters themselves with their crusher claws. There’s all sorts of hooked and sharp things aboard a fishing boat, and there’s the hydraulic haulers to take a finger off. But most of all, there are the ropes. Warp scatters everywhere; good lobstermen will keep their warps organized, lines coiled and out of the way, where they need to be, and so will the bad lobsterman. Highliners and dubs alike, they keep the ropes neat. The only lobstermen who don’t keep their ropes neat are the dead ones.

Scotty hadn’t bothered taking the floating rope off the bridles on the traps, and he left the pair of traps still lashed together; the warp was tangled up in a bundle around his feet. Scotty was struggling to get one trap stacked up on the other, and the top trap was half on its twin, half on the railing, and that big, stupid fucking Newf, Second, was barking and nosing at Scotty. I can’t remember if I was watching the whole time, if I saw Scotty straining with the traps, a nine-year-old trying to be a man, trying to live up to Daddy, to live up to the name that he carried with him everywhere he went on and off of Loosewood Island. I can’t remember if I didn’t offer to help because I was a twelve-year-old girl and busy with simply not being near him, or if I didn’t offer to help because I knew that he would never live up to the name he carried with him, that he wasn’t deserving of it in the same way that I was. What I do remember is the sound of Second’s barking.

Daddy heard the barking, too, because he looked over his shoulder and yelled out, “Second. Get off him!” But as he yelled at Second, the Queen Jane caught a wave. The boat gave an unexpected bounce, and it wasn’t clear if Second stumbled into Scotty or if Second jumped onto Scotty, but the results were the same: the trap that Scotty was balancing on the rail went over, and Scotty fell in the tangle of ropes on the deck of the boat.

I wish I could say that something spectacular happened, that the ocean flattened into glass, sea turtles rose to encircle the Queen Jane, the weather crackled black, and the winds cursed at us, ripping a hole in the clear blue sky as water spouted into the air like hissing serpents. And I’d like to believe that we all had a chance to realize what was going to happen, that Scotty and I locked eyes, and that Daddy, in that moment, understood that our family had a history that couldn’t be ignored. But I know better than that. There was nothing to set this moment aside from all of the other moments that came before and all of the other moments that came afterward. There was no magical marker to delineate then and later, no animal from the deeps reaching out and drawing Scotty away from us. It was just an accident. It was just the ropes.

Scotty fell to the deck, slipping in and under the ropes, the first trap hitting the water and yanking tight the lines to its twin. The warp snapped against him, and I could see a piece snug across his throat, his body slamming into the trap, and then the whole mess—line, trap, Scotty—crashed into the rail and flipped over and out into the water. The buoy smacked against the rail, the last thing out of the boat, bouncing into the air and then settling in the deep.

Second, barking, went over the stern and into the water to save Scotty, unable to leave him alone even after he’d knocked my brother overboard. There wasn’t time for Daddy to try to throw the boat hard in reverse—from Second knocking Scotty down to the time he was in the water wasn’t even enough for a blink, like a car crash or a bullet wound—and instead Daddy did the only thing he could do, which was to slam the throttle full forward and crank the wheel, turning the Queen Jane nearly on her edge. He reached out to me and grabbed my shoulder, and it was suddenly like I had woken from a daze. “Turn her around,” he said. “Line me up.”

Even though I was still short enough that I could barely see through the glass, I kept the wheel hard to starboard. The boat turned against the waves and, though the sea was calm for that time of year, I glanced back to see Daddy stumble as he went for the gaff.

I stood on my tiptoes and could see Second moving swiftly across the water toward the buoy. The sky was clear and the sun hung up so that it bounced off the water, Second’s black fur glistening in the light and the wet. A series of shadows cast through the water and under Second, a school of fish or just a play of darkness.

“Off the throttle, honey,” Daddy called, and his voice sounded so calm, so reassuring, that I half-wondered if I was in some sort of a dream, if Scotty was in a mermaid’s castle, if my grandmother would come flying through the water, if Second would simply pluck my brother from the sea.

How long did it take before Daddy pulled the rope back and started hauling it by hand? Half a second? One? Two?

Second barked, and then barked again, and started swimming in a tight circle around the buoy. He kept ducking his head under the surface. I lined up the boat, one cold hand on the throttle, one cold hand on the wheel—I wasn’t wearing mittens, for some reason—and I heard Daddy yell, “Stop her!” He meant for me just to throw the throttle into neutral, but I panicked and killed the motor, killed all the power on the boat, killed everything.

Daddy gaffed the rope neatly and slapped it into the hydraulic, but nothing happened. When I killed the motor I’d cut the power to the hydraulic; the rope hung tight, not moving, doing nothing to take Scotty from the depths.

How long did it take before Daddy pulled the rope back and started hauling it by hand? Half a second? One second? Two?

Second kept barking. With the motor cut, the sound of the dog and Daddy’s breath competed with the waves and the few gulls overhead.

Maybe a minute had passed since the dog had knocked Scotty into the traps. I left the wheel and hurried to start stacking the wet warp—the rope—on the deck behind Daddy, though I had no hope of keeping up and no real sense of why such a thing would be useful. We were over the shelf, and the water wasn’t that deep—three, four fathoms—which was the only reason why the buoy, with all that fouled line, still shone on the surface. By the time I got behind Daddy, he’d already pulled twenty feet of warp from the water, the first lobster pot breaking the surface. I gasped at the sight of my brother’s body: he was pressed tight against the trap, a loop of warp around his neck, the rest of the line tangled against his nine-year-old body and the trap, his arms splayed out. When he broke the surface, he wasn’t breathing and his skin had turned pale and headed to blue, though I didn’t know if it was from the cold or the lack of air.

I couldn’t look at my brother, and I couldn’t look away, but there was something to the side of him that caught my attention: a small movement among all of the other movements of the waves and the water. I leaned over the rail and extended my hand toward the water, the sun and the reflection of my fingertips in the foam bouncing back to me, and for an instant I thought it was not a reflection, but some other creature reaching from the water to grasp at my hand, to pull me under. And then that instant was broken by Daddy’s voice.

“Call it in, Cordelia,” Daddy said.

Alexi Zentner is the author of Touch: A Novel, which was published in a dozen countries. A Barnes & Noble Discover Great New Writers pick, Touch was shortlisted for the Governor General’s Literary Award, the Center for Fiction’s Flaherty-Dunnan First Novel Prize, and the VCU Cabell First Novelist Award, and longlisted for the Scotiabank Giller Prize and the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award. Zentner’s fiction has been featured in The Atlantic and Tin House. He lives in Ithaca, New York, with his family, and his second novel, The Lobster Kings, will be published in May by W.W. Norton.