Mary’s welcome was enough to persuade him to come down.

His eyes were exactly the same as those in her nonexistent memory. Green and black, with that cheerful chaos that indicated he had come from the other side of the day. Anything that might matter to the living was, for him, simply the childishness of being. At first, Mary was scared to look at him, to see the path decomposition had carved through his flesh, but Howard was nothing more than a beggar fraying around the edges, certainly unwashed, but hardly disgusting.

When Cub left during the day, he came down from the attic. They had so many things to tell each other. She brightened at the thought that she finally had a companion capable of understanding her. Just when she’d lost all hope. He didn’t actually talk, but he was there: present. Not a dream, not a nightmare or a hallucination. He was, specifically, beyond all that, because life took on forms that nobody could have ever expected.

One day, Howard took her by the hand. He wanted to lead her through the streets of London. He wanted to show her what he loved about this city that had killed him. He had lived his final years like an animal, in total destitution, he said, defecating under the bridges or on top of the roofs. He pointed out the gaps along the road and the absences among the people. She could see clearly the holes that the dead left in the lives of the living. She certainly was the only one able to distinguish these grayish, melancholy forms, but she told herself that knowing what they were was a sign of permanence, that nobody ever truly left. The beggar whistled, happy in her presence: I’ll show you something to make you change your mind.

Change my mind about what? she asked, intrigued. About the need to live? Here, especially, where old age isolates us from an incurious world, since it has nothing to do with us? I don’t recognize these roads where I lived so long ago. Now I see both the empty and the full. The emptiness, for example, of the woman selling fake jewelry, each one for two pounds, whose face caked in orange makeup gets more wrinkled every day and who has a smoker’s voice, warm and rough. There’s a gray rectangle on the ground where she usually sits, and the wind blows colder there.

And further on, the man hawking christening gowns, lace dresses billowing around absent bodies, pink-white-creamy babies, so fine that they look like drops of milk curdled by honey and bees. He’s no more there than she is. And the babies who were once in these gowns? Where are they? What has become of them? Those rounded cheeks, those eyes gleaming with their discoveries had to have been lost to history. Unless they had been the features of people who did help change the world. Mary smiled at the thought that Marie Curie might have once worn a gown and some lace just like the ones here. And radium had been discovered even so!

Those she met now were eyeing her like an alien, chewing gum and forcing her to see the grayish, glutinous paste in their mouths, rolling around their pink tongues. She was in a place where people walked in the haze of others, a place where they slipped in the oil slicks of other people’s gazes, where nothing was theirs—not even the air other people were breathing frenetically, not even the wafts of foreign spices, not even one’s own body which continued obstinately seizing on whatever life it could.

Her back was hunched by guilt, knowing that every glance underscored the certainty of her uselessness, that as soon as she was gone, someone newer, truer, more deserving, would fill her shoes and this space with no fear of the total indifference she absorbed, she a blotter for the most precious inks of life, she a criminal for being so old yet enjoying forbidden happiness. She kept on walking beside Howard and realized why the city hated her so much. I’m an ever-growling belly that has to be fed, and fed, and fed, she said.

Howard smiled. You’re wrong, he replied. We aren’t useless. My life smelled like newspaper ink and pulp because I slept on newsprint and used it to stay warm in the winter, but the latest news never haunted my dreams. What did words matter to me? I knew that every kind of paper, from the lowliest tabloid to the most prestigious, spread lies that buried their readers in a placid stupidity. None of them talked about this world of piss and filth that I lived in, about the underside of London. That’s where my true friends could be found, until hooch or drugs had wrecked their liver and guts. It was just one of many ways for them to die. Cancer or heart attack or car crash or cirrhosis of the liver: is any sort of death easier than another?

I came back from the war without a soul. My heart broke in the pits of Dunkirk. The trenches welcomed my dreams just as easily as they did my friends’ guts. They carried me out on a stretcher and, despite all the efforts of the nurses—no matter how angelic or surly they were— to fix my body, they weren’t able to fix my spirit. I went mad. They let me leave, but I was never able to make my way back to Benton-on-Bent, or to take up my trade as a mechanic, or to reconnect with my family and my friends. I landed on some other planet, and the only ones who could understand me were the veterans who, like me, had been trapped within the eternal night of war.

Mary, I spent years on the streets. I discovered an England that nobody knew: fat women smiling giddily, thin girls sweating scornfully, men who became my brothers, brothers who had been my enemies. I saw the whole gamut, Mary. What all the men had in common was that they were different. There wasn’t any general trend. There were only personalities nobody could have guessed they’d had when they were born. I met them all. I lived unnoticed in attics where I heard people living their real lives. My God—what an impoverishment! Do you know how many days and weeks and months I spent listening to the same arguments, the same excuses, the same inanities? Was this what we fought for? Was this why we survived?

One evening, after eating nothing for a whole week and hearing a girl whine about her boyfriend refusing to buy her the latest phone, a teenager shouting at her “clueless” parents, a husband telling his wife he was settling down with someone younger, and then the wallpaper and then the phone and then the old shoes and then and then so on so on so on and all this complaining about not having things that had nothing to do with the emptiness in my stomach, the dizziness in my head, the hopelessness in my mind, the sadness in my heart, I went out, and I climbed to the top of the Post Office Tower—I’d slipped through the barriers and the forbidden areas so many times that I had no trouble getting in this time. The elevator got me higher than the level of London’s rooftops, which might as well be the roof of the world. I saw London spread out at my feet, a beautiful city after all, such a beautiful city, built out of wartime stagnation to become a symphony of illumination and jubilation for those who claim this city as their own, but I was on the losing side and the city’s beauty didn’t console me, didn’t signify anything for me, the worst thing for us wasn’t the void so much as the surplus of other people: they had all decided that I was an outsider.

That night, I jumped from the top of the Post Office Tower while spreading my wings of newsprint. As I fell, I thought I could see people eating in the restaurant that used to be at the top of the tower, eating food so expensive that it could have fed me for a year or even ten. It could have been wine worth three thousand quid or it could have been piss; I didn’t care. Their stomachs weren’t any more deserving than mine. Their stomachs weren’t digesting food any faster than mine was, and their shit wasn’t going to stink any less than mine. If they had just looked and seen me falling on the other side of the glass, they would have understood that their fall would have been every bit as deadly. And just like that, every dish they ordered would have started tasting completely flat, like it was just chewed-up money. The wind was rushing past the tower so hard they were sure it would fall. That’s the fate of all towers, after all, to fall. And so I was hurtling headlong, without making a sound. Which was fine, that was how I ended up in the local news with a couple of paragraphs about a bloody explosion. I hadn’t read a single word of those papers I had wrapped around myself every night, and there I was all the same: MAN JUMPS TO DEATH SPLATTERING THE GUTTER PRESS. A man in the gutter, that’s what I was.

Now, come with me.

Mary took a few more steps. They headed toward the river together. Mary’s sadness was immense, deep, territorial. But, as she watched Howard out of the corner of her eye, she was sure she saw colors slipping out of his hands, like the lights that hung around the top of the tower.

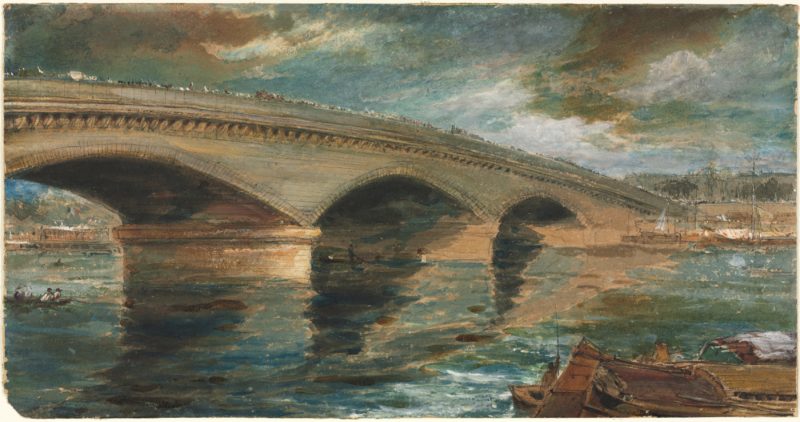

He dragged her to the Thames. Her icy feet stumbled in the slippers she’d forgotten to change before heading out. She walked toward the edge of the water, following him down winding paths along the canals and beneath the bridges, paying no attention to the junk and refuse they came across, the boys and girls enveloped in musty odors or stippled with pinpricks, old people who might as well have been dead, young people who might as well have been old, rubbish thrown from the bridge and which testified to that horrible propensity to throw away, to keep on throwing away what could be used, clean sheets of paper, half-eaten food, outdated television screens, broken computers, everything had been thrown out, everything had been abandoned with absolute indifference in a landscape of ugliness, and it seemed almost intentional that nature should only offer brambles and thorns that bristled against all who would enter.

But when she finally reached the river’s edge, things changed. The clouds moved apart to let through a huge outpouring of sunlight. The water responded in kind, saying Hello, hello, dear to the sky. Mary was astonished by their mutual gleaming. She froze there, charmed and amazed at the same time. She had the impression that it was Howard who was making the daylight dance.

A barge came through with sharp ululations. Seagulls dive-bombed. The air was tumultuous. The water exuded an unusual warmth. A smile sloshed around her stomach, flipped around like a carp.

She looked straight at the sun, waiting for it to descend. The few people strolling nearby, all too aware of the river’s treacherous coldness, lingered in fascination. They, too, seemed captivated. They even smiled at Mary. Suddenly she was no longer invisible.

A waltz with Howard, the exalted beggar.

Thank you for this gift you’ve made, she said, looking straight at him. His eyes were like a greenish fog, like damp seaweed. The green of stalks that could be parted the better to see the lethargic water beneath. But no, nothing in Howard was lethargic. He was livelier than the living, newer than a newborn, he was ready to bound into the foam, to get drunk on the air, even if it was polluted, to go wild with everything that, in this old, old city, tired of all these charades, still had a child’s radiant smile.

In this old land of new evils, Mary, he finally said as he sat down, they learned how to cry for the death of a princess the same way they learned how to forget her after—this new civilization of shaky morals and fleeting tears—and two ten-year-old children could kill a three-year-old child for no reason, with no hatred, can you imagine that, we all thought killing for the fun of it was done only by grown-ups but no, children have always been doing it as well, it’s just that now they’ve switched from insects to people because there’s nobody around to tell them what they can or can’t do, in this land unpunished crimes are acceptable crimes, we can only judge those who have been caught, and these new evils, Mary, have embedded themselves in the scabs that had already formed over the wounds of the old city, and they will go on doing so. Call no man happy until he is dead.

Feel how light this dance is, and how bright this light that once had been so blinding—now turned by alcohol into the pinpricks of a headache, into bubbles of champagne with their heady, intoxicating fragrance; feel how we are wasting our life on this earth.

Mary listened to him, at once surprised and seduced. Wasting our life on this earth? Was this what she was doing as she slid inexorably toward her death? Was this what happened to people when they got old—the earth working to get rid of them and abandon them almost before they’d died, leaving them as lost as things that people no longer needed? Or were they the ones who were losing their sense of life?

Have we gone astray in this life? Nothing beckons me onward, nothing holds me back. If there were an eraser that could scrub me away…said Mary. Howard reached into his satchel and pulled out an artist’s eraser. Which part do you want me to erase first? he asked with a smile. Mary considered the question. Not her feet, since she still needed to walk and wander and discover all these new things she’d never even guessed existed. Not her hands, because she still needed to grasp, no matter how maladroitly, the materials of her visions. Not her eyes, because she still wanted to see, and see more of, Howard’s face and Cub’s face, Cub’s body.

Suddenly she knew.

Words, she said, erase my words, because I don’t have anything to say that’s worth hearing.

With you, I can talk without words.

Tenderly, Howard took her face between his hands, tilted it toward the light. The golden moisture of the air exhaled microscopic droplets on this fragile parchment. Just beneath her skin could be seen the latticework of veins, the bluish network that still traced the trajectory of Mary’s life. Howard knew the different phases of Mary, as a precise calendar would those of the moon. He applied the eraser to a mouth that was nothing more than a very pale dividing line, and he set to erasing the words hidden there, all the words of her sadness. Across Mary’s blue eyes there flitted a quick fear like the wing of a bird in the night. Then she was calm again as she gave up the words she no longer needed.

Now, said Howard, the only words you have are the happy ones.