I began reading John Irving’s fiction in the summer of 1974. I was twenty-three years old and likely the youngest student in the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop at that time. It was the beginning of the fall semester and I was buying the books for my classes when I came across a paperback edition of his second novel, The Water-Method Man. I figured I ought to read it, since for the next few months I was going to be working with the author. I read it straight through, practically in one sitting. It was darkly comic and brilliantly tragic, and I knew that this was who I wanted to teach me how to write novels.

As it turned out, John became my mentor for the duration of my time in the Workshop. I liked him because he was young, he was funny, and he was kind. But more than that, he was a storyteller, which made his classes almost as entertaining and compelling as his novels. Did he teach us anything about writing? No, not really. In his memoir, The Imaginary Girlfriend, he admits as much: “I didn’t ‘teach’ Ron Hansen or Stephen Wright or T. Coraghessan Boyle or Susan Taylor Chehak or Allan Gurganus or Gail Harper or Kent Haruf or Robert Chibka or Douglas Unger how to write, but I hope I may have encouraged them and saved them a little time.”

Avenue of Mysteries, Irving’s new novel about two Mexican “dump kids”—the reader-turned-writer Juan Diego and his psychic sister Lupe—is full of sly, self-referential bits that are akin to offerings for a constant reader. Lions, mangled appendages, strange speech, writers and doctors, virgins and Jesuits, circuses and orphanages, dogs and dwarfs, Iowa, eels, and more—all the familiar motifs. Even Irving’s own practice is mirrored in Juan Diego, a storyteller on a par with his creator.

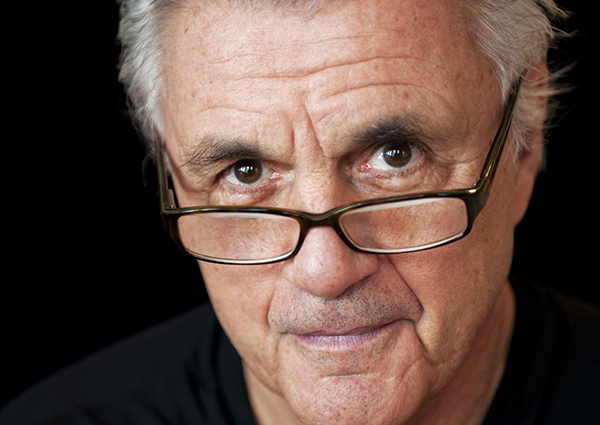

Irving—whose books include The World According to Garp, The Cider House Rules, and A Prayer for Owen Meany—is the rare novelist whose work is admired by writers, acclaimed by critics, and beloved by readers. The latest, Avenue of Mysteries, was published in November.

—Susan Taylor Chehak for Guernica

Guernica: I used to come to our meetings at Iowa equipped with a cup of coffee, a pack of cigarettes, and a small red ashtray, then just sit back and listen to you tell stories. I don’t remember you ever talking about actually writing fiction, or teaching us anything specific about craft or technique.

John Irving: I have a process that I seem to always, to some degree, as a writer, adhere to, but I certainly have never imposed the way I write a novel on my students. When I had students, I never said, “You should never start writing a novel until you have the last sentence.” I never did that, and I wouldn’t do it now, but people now seem so interested in the process [of writing fiction] that I have to constantly make it clear when I describe mine that I’m not being prescriptive. I’m not proselytizing.

Guernica: Are you still working on a typewriter?

John Irving: I’m not typing. I write only by longhand. I’ve always written first drafts by hand and then once I was into a second or third draft I wrote insert pages on a typewriter. But I got rid of all my typewriters about three or four novels ago and now I do everything by hand. I write by hand because it makes me go slow and going slow is what I like.

Guernica: I read Avenue of Mysteries slowly, I think because I wanted to stay with it. But after I was finished, it stayed with me. Other people have said this about your work, and maybe the reason for this is because of what Juan Diego says: “Sometimes the story begins with the epilogue.”

John Irving: I suppose in the writing of the first three or four novels I imagined that it was a kind of curiosity—even to me—that I seemed to know more about the endings of my novels than I did about where they began. Not to mention the fact that beginnings were much easier to change. It is much easier to be flexible about where a story begins than it ever was for me to change my mind about where and how a story ended.

The ending seemed absolute and yet I imagined that one day I would begin a novel at the beginning like so many other writers do, including many of my friends. But the concept of writing a novel and not knowing where it’s going—I don’t know how to do that. Novels are plot- and character-driven, so if I don’t know what becomes of people, how can I know where it should begin? After three or four times, I just accepted that [the book] works better if I know everything I can about the ending. Not just what happens, but how it happens and what the language is; not just the last sentence, but enough of the sentences surrounding that last sentence to know what the tone of voice is. I imagined it as something almost musical. Then you are writing toward something; you know the sound of your voice at the end of the story. That’s how you want to sound in those final sentences: the degree that it is uplifting or not, the degree that it is melancholic or not. You know what it is.

Guernica: And if you don’t have that ending, do you wait for it to show up?

John Irving: As many years as I took notes on books that I kind of let sit—like boxcars in a train station uncoupled from an engine—they just waited. I knew a lot about them. I knew a lot about the characters. I knew a lot about the story. The setting. I had all these notes accumulating, but if there wasn’t an ending, I never imagined that it was time to begin that novel. And so sometimes, in fact for most of my life, when I’ve finished the book I’m writing, there’ve always been as many as two or three other novels waiting to be written next. And the decision driving which one of them it should be was never based on how long it had waited or how many accumulated pages of notes I had.

The hard part about going to orphanages is when you go back a second time.

Guernica: Juan Diego compares writing a novel to treading water and dog-paddling: “It feels like you’re going a long way, because it’s a lot of work, but you’re basically covering old ground—you’re hanging out in familiar territory.”

John Irving: Yes. In fact, for the first time, in the writing of Avenue of Mysteries, I already let one of them go. Because I recognized it was a novel that I’d held too long and I no longer felt up to the kind of novel it was. So I gave it to Juan Diego. I made it the novel that he would never get to finish. But if that novel [One Chance to Leave Lithuania] seemed convincing for Juan Diego to be writing, well, it’s a novel that has been waiting for me to write it a long time.

I recognized, around the same time I began Avenue of Mysteries, that One Chance to Leave Lithuania was one I should have written ten or fifteen years ago if I was going to do it. That I did not feel like spending another couple of winter months in Vilnius, in Lithuania. I didn’t feel like more orphanages. Because, here is something I learned when I was looking into orphanages, years and years ago when I was not yet writing The Cider House Rules, but taking notes and thinking about it: the hard part about going to orphanages is when you go back a second time. When you go the first time, nobody looks at you. That is, the kids don’t pay any attention to you. But if they see you twice, then they think you might be there for them. And that’s a tough one. To suddenly find some little hand in your hand, saying, “Take me. I’m the one. Take me.”

I thought, You know what? I’m not going again to Vilnius in February. I’m not going to another orphanage. Done that. Been there.

Guernica: How long have you had to wait to find the ending that’s right?

John Irving: Twisted River waited twenty years before I started writing it, because I had my doubts about the ending. I knew everything else, but I didn’t know the ending, and therefore I wasn’t prepared to say, “The first chapter begins here, because that’s where it should begin, knowing where it ends.” I’m not smart enough to know how to foreshadow something if I don’t know what it is.

Guernica: Twenty years?

John Irving: People are kind of appalled when I say Twisted River was sitting around all that time, and then there were another three years after that. But I was writing a screenplay at one time, more than twenty-five years ago. It was set in India, about children as high-risk performers in a circus. It was never made. I put it away. I relocated that story in Mexico. I wrote it as a screenplay there. But I didn’t go to the Philippines until 2010, exactly when Juan Diego goes there. And by the time I went to the Philippines I already had a shopping list of what Juan Diego thought he was going to see, as opposed to what I knew he was going to see.

Guernica: Juan Diego’s sister Lupe is thirteen and she can see the future—at least her own and maybe her brother’s, too. You have said: “I’m drawn to characters who see the future, or think they do.” Which is like you, because, as you say, you know what’s going to happen in the end.

John Irving: Well, this is not the first time that I’ve brought one of my characters into a little bit of what I know—that I’ve given one of my characters a kind of dubious gift, namely, that they can see a little bit of the future, or think they can. Owen Meany was such a character. Lilly in The Hotel New Hampshire was such a character. She jumps out a window because of it. It’s not necessarily a good thing, to know. It can be a burden, and the younger you are and the more isolated you feel, maybe the more of a burden it is.

Guernica: The future is a mystery to the rest of us. Is faith a mystery, too?

John Irving: I’ve always been interested in miracles, or the miraculous of the unexplained. I don’t scoff at what makes people believe or want to believe. I think I understand the tremendous attraction of the mysteries of the church to the same degree that I understand and appreciate the frustration people feel, especially believers, with the human rule-making arm of the church, with the not-miraculous part of the church—any church. I suppose I believe what the old dump boss Rivera [in Avenue of Mysteries] says in the temple to the two old priests, as he points to the statue [of the Virgin Mary], who has shown him her tears: “I don’t come here for you—I come for her.” I get that.

I think this novel sort of stands up for the mysterious and the miraculous while casting a dubious eye on those spokespeople for the church, who tell us how we should behave and what everything means. In the beginning, Lupe makes fun of Rivera as a Mary worshiper, and Lupe has her doubts about Mary. But Mary gets the last word. And if Juan Diego wasn’t a little bit of a believer—a doubter, but a believer—to me it wouldn’t work, because at that moment when the statue of the Virgin cries, no one looks as much of an asshole as the atheist.

I’ve always thought that atheists and true believers proselytizing their faith to other people have a lot in common, a lot more in common than they would like to admit.

Guernica: When A Prayer for Owen Meany was published, you said: “I’ve always asked myself what would be the magnitude of the miracle that could convince me of religious faith.” Isn’t this the question that Avenue of Mysteries is asking as well?

John Irving: I’ve always thought that atheists and true believers proselytizing their faith to other people have a lot in common, a lot more in common than they would like to admit. They’re both proposing to know something about which neither of them can know. They have not died and come back to us and told us what’s there. Whoever the fuck they are, they haven’t done that.

Guernica: In Avenue of Mysteries you quote Jeanette Winterson, from her novel The Passion: “Religion is somewhere between fear and sex.”

John Irving: That could have been the epigraph for this novel. But I just loved the Shakespeare [quote that acts as the epigraph] so much I couldn’t lose it, and it was a toss-up. I love that novel, The Passion. It’s my favorite of Winterson’s novels. I love that quote and my novel is about fear and sex, but it’s also a novel about, as the line from Twelfth Night says, how journeys end with lovers meeting. I just couldn’t let that go. Also the fear and sex seemed to give a little too much away.

What Winterson doesn’t say in that line is also what The Passion is about, which is that [religion is] very funny, until it isn’t. It’s very funny until suddenly it’s very melancholic and dark.

Guernica: And the biggest mystery of all is death?

John Irving: It is. I think everyone but Juan Diego seems to know that he’s on his way there. Certainly the reader knows. You read in the first chapter that he’s got a heart condition and he’s being a bad boy about taking his meds. And I’m sure it’s not lost on many that those two women all in black, those mourners that we see for the first time when Rivera carries Juan Diego into the temple with his newly run-over foot, that they haven’t ever gone away. They’re still attending to him whether he recognizes them or not.

Guernica: When we first meet the character Edward Bonshaw in the novel, he regularly engages in self-flagellation. Didn’t you once see a man doing this at a screening of The Last Temptation of Christ?

John Irving: Yes! With a belt! He was smacking himself with a belt. I keep thinking about that. It was a great moment. And I was really disappointed when the theater people came and made him leave. I thought, Jesus Christ, don’t take him away! I mean, he’s enhancing everyone’s experience here.

Guernica: Funny till it’s not?

John Irving: Yes.

Guernica: What’s next for you?

John Irving: I’m writing an adaptation of The World According to Garp as a miniseries for HBO.

Guernica: Does it matter to you that it’s already been a successful film?

John Irving: It would, if it had been the movie that I would have written or hoped to have seen. I talked to [director] George Roy Hill many years ago when he asked me to write the screenplay and I said, “I don’t think you see the same movie in this novel that I see,” but we were friends and we stayed friends until he died. I don’t know if we would have stayed friends if I had been his screenwriter.

Guernica: What attracts you to writing for television?

John Irving: The sense of structuring [a story] in episodes and titling each one of those episodes, as I would do. That’s appealing to me. Also the element [of precognition] we’re talking about in Avenue of Mysteries—namely, a teleplay that’s going to be shown over five or six episodes allows you to do the kind of foreshadowing that I love doing in a novel. You can flash forward to moments or scenes that you have not yet encountered in so-called “real time,” while at the same time you can always flash back. In an episodic treatment, such as a teleplay is, you have the ability to do what you can do in a novel, which is flash back and flash forward in the same instant, in the same scene, in the same voice.

Not to mention the fact that you’ve got an opportunity in the opening credits in the title sequence. For five episodes you can use that title sequence to show the audience an interesting mix of what they’ve seen before and what they have a reference to and what they’ve never seen before and you’re saying: “This is something you will see but you haven’t seen it yet; this is something you have seen, you remember that, don’t you? Oh sorry, this is something you haven’t seen yet, but you will.”

Guernica: But you can’t really do that in a novel, can you?

John Irving: Oh, but you do do that. I do it in this novel. I often write stories on parallel tracks. A lot of Twisted River was done that way, but it’s very easy in this case, too. For example, I first wrote Lupe and Juan Diego’s story—what happens to them when Juan Diego is fourteen and Lupe is thirteen. Just that story, from the moment Brother Pepe discovers the Dump Kids, one of whom is a mind reader and the other of whom has taught himself to read. That’s the beginning.

I wrote that as a screenplay. Many drafts of it. And looked at it and thought about it and thought about it. I thought, Okay, it’s a movie, but don’t do anything about it as a movie. Instead, think about what happens if we meet Juan Diego thirty, forty years later, what would he be doing? What happens if and when he ever does make good on his promise to the Good Gringo, that he will go to the Philippines and pay his respects to the Gringo’s dead father if the Gringo doesn’t make it? What about that trip?

And so I had the idea of a novel that would be constantly told on those parallel tracks. A little bit of Juan Diego leaving for the Philippines. An older man with a limp who looks ten years older than he is.

And of course I knew that the reason Juan Diego thought he was going to the Philippines was not the reason I wanted him to go to the Philippines, because I knew I was going to bring in those two women all in black that he saw for the first time briefly when his foot was just crushed. I knew they were coming too. And I knew that he was never going to get to that cemetery to pay his respects to the Gringo’s dad, that he had another destiny in yet another place where the Spanish came for 300 years and brought the church with them.

So the flash back, flash forward—you can do it. This novel is a lot like a film, even though if it ever is a film the only part of it that will be filmed is the Mexican part of it. That’s all it will be.

If you have an imagination—which Mark Twain didn’t, which Henry James didn’t, which Sigmund-fucking-Freud didn’t—you can imagine situations that you’ve never been in.

Guernica: Clark French, Juan Diego’s former student, tries to get his teacher to take sides in the debate about autobiography versus imagination in fiction: “Using autobiography as the basis for fiction produces drivel. Using your imagination is faking it.” Clark insists that Juan Diego is “on the imagination’s side.” That he’s a “fabler, not a memoirist.”

John Irving: Clark is an asshole, but he’s also on the right side of a few issues. And I think he’s on the right side of that one. He’s a bully and a proselytizer, but he’s also someone I feel some affection for as a character. Also, I always thought that you could do worse than find yourself dying in the company of a devoted former student. And I certainly am on Clark’s side in the case of Shakespeare. All the unimaginative assholes in the world who imagine that Shakespeare couldn’t have written Shakespeare because it was impossible from what we know about Shakespeare of Stratford that such a man would have had the experience to imagine such things—well, I agree with Clark that this denies the very thing that separates Shakespeare from almost every other writer in the world: an imagination that is untouchable and nonstop.

If you have an imagination—which Mark Twain didn’t, which Henry James didn’t, which Sigmund-fucking-Freud didn’t—you can imagine situations that you’ve never been in and put yourself in the shoes of characters whom you’ve had no personal contact with.

Guernica: Toward the end of Avenue of Mysteries, Juan Diego wakes to “discover what looked like a title—in his handwriting—on a notepad on his night table. The last things, he’d written on the pad.” Juan Diego is a mature writer, and so are you. What’s changed for you over the years you’ve been writing novels?

John Irving: If anything has evolved about my process over this, now my fourteenth, novel, it’s that I’ve always been slow but I’m even slower now. I’m more into the waiting, or I guess I’m more patient about the waiting. And one of the reasons I went back and forth and with some reluctance agreed to write this teleplay for HBO is that if I didn’t agree to it, I was afraid I would begin one of the things I’m thinking about beginning too soon. Because I don’t know as certainly as I usually do which of these two very well-developed novels I’m considering really is the one I should do next. I thought, Oh, okay, it wouldn’t hurt to have something else ahead of me.

And this process, my talking to you, my talking just endlessly to people over the coming months—US book tour, a Canadian book tour, a UK, a Norwegian, a Netherlands book tour, a French, Spanish, German book tour, probably a book fair in Guadalajara or Oaxaca—Jesus Christ. I said, “I can’t write a novel.” I said, “I don’t want to be trying to write a novel. I can’t even find the fucking time to write the teleplay of something I was writing forty years ago and I know everything about it.”

A part of that is, I’m more easily exasperated and distracted by the things I don’t want to do than I used to be. And a part of that is just my fault in getting older, and a part of it is also the fault of how much more desperate and scatterbrained publishers are now, for understandable reasons, than they were: that their own business is in flux or in jeopardy or both and they don’t know exactly what to do but they just want their authors to be doing more. Even at the expense of writing my next book or the book after that, they don’t give a shit how much time I spend talking about something that’s already behind me. If my talking about something that’s already behind me over and over again serves them, they’re going to ask me to do it, every time. There’s going to be no end to how many times they’re going to ask me to do it.

Guernica: You can’t say no?

John Irving: How can you say no? You can’t have it both ways. You can’t say no and not help them and then pick up the phone and bitch because they sold fewer copies of this book than they did of the last book. It’s not that what they’re agonizing about isn’t part of what I recognize is also happening. People aren’t reading fiction the way they used to read fiction and the fiction they are reading, much of it, is shit.

Guernica: You gave One Chance to Leave Lithuania to Juan Diego as his own book instead of yours. Didn’t you also give Garp things that you had written?

John Irving: Yes, but that’s a little complicated, because it’s only because of the order of publication that you think of those things I gave to Garp as things I had written. But I had written those things for Garp. In other words, I wrote “The Pension Grillparzer” as a story Garp could have written out of his years in Vienna that would demonstrate that he was a real writer. [Otherwise] I never would have put the effort into that story that I did put into it, because I didn’t and still don’t have much interest in short stories, writing them or reading them.

Guernica: Juan Diego is a novelist in that way, too. “[H]e could concentrate on the long haul; he’d never been much of a short-story writer.”

John Irving: Well, having just said what I said about short stories, I make exceptions. I love Alice Munro stories. I love your old classmate Tom [T.C.] Boyle’s stories. And I love Stephen King’s stories. In fact, there’s a story in his new collection of stories that’s dedicated to me. It’s a story that sets up everything you’re supposed to see coming and because it’s so painstakingly foreshadowed, you think, Oh, I see what’s coming, of course. But he does a very clever job of making the things he foreshadows become of seemingly increasing importance; the foreshadowing keeps accumulating. You think, Oh, that’s what I have to keep my eye on, and you forget about the previous innocent/not-so-innocent-seeming thing that you have been warned about. And I’m sure that every reader, like myself, will simply forget about the one thing you should be remembering. I kept reading the story thinking, Why is this dedicated to me? What’s he doing? I was liking the story, but I kept thinking, Why this story? I mean, it’s okay, but why is this about me? And then, all of a sudden, he just took me in and I missed something that I should have had at the top of my list of things to remember. And as soon as it happened, I thought, Oh shit, of course. I should have seen that coming.