Every winter for the past twenty-odd years, I’ve received the postcard in the mail, exhorting me to enter the Dancing Poetry Contest, sponsored by the Artists Embassy International in Northern California. The prizes are modest, but the winning poems, the advertisement always reads, are performed by Natica and Richard Angilly’s Poetic Dance Theater Company at the annual Dancing Poetry Festival, with costumes, sets, and lighting. I always found that intriguing, if only because I didn’t quite grasp the concept. How could a poem be danced? I guessed it was open to interpretation.

Dancing to poems has become, in the past year or two, something of a trend. While the Dancing Poetry Festival, now in its twenty-third year, was the first event to recur annually for more than two decades, others have recently debuted, including: Northern Michigan University’s Desire: International Poetry, Music, and Dance Festival, sponsored by the English honor society Sigma Tau Delta and the NMU departments of English, music, and modern languages and literatures; the Ecstatic Poetry and Dance Festival, dedicated to Rumi and his spiritual ilk; Boulder’s Poetry in Motion Fringe Festival performance; and The Poetry Project by Miami Dance Festival, presented by Momentum Dance Company, in which one of my own poems was used in 2014. In some cases, poems are presented orally and rendered in dance—why shouldn’t a piece of prosody like “My Papa’s Waltz” literally be waltzed to?—and sometimes the poems function as music, through meter and alliteration and assonance. In Miami, the dancers wore basic black leotards and skirts, and the poems were inscribed in parts on their bodies and clothing so that the audience could “read” them throughout the movements. Where typically rhythm is supplied by recitation, chimes and cymbals filled the silence.

This increasing interest in how to express poetic thought through the body comes with questions: As we become less of a mono-linguistic society and more of a multicultural and multi-literate one, will dancing our poems someday take the place of reading them? Will poetry eventually be written in the language of choreography? Or will there be an altogether new language for it that combines poetic thought and bodily movement?

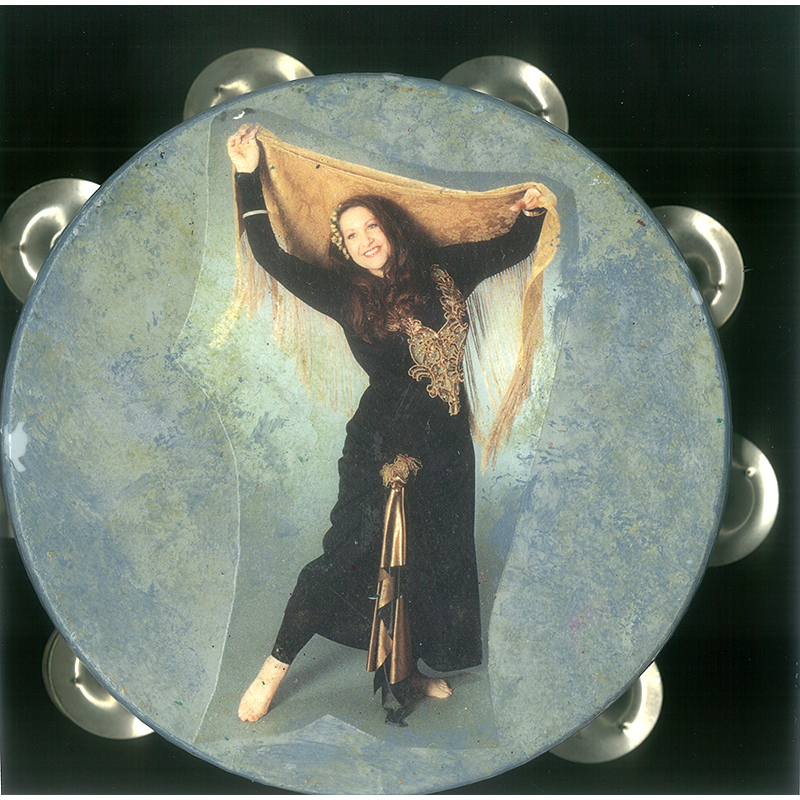

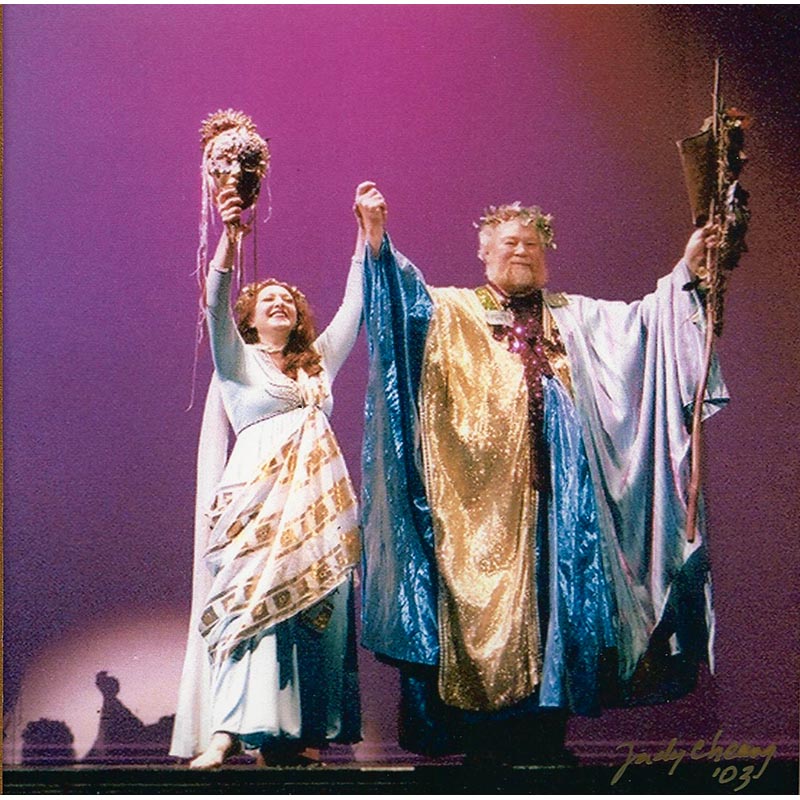

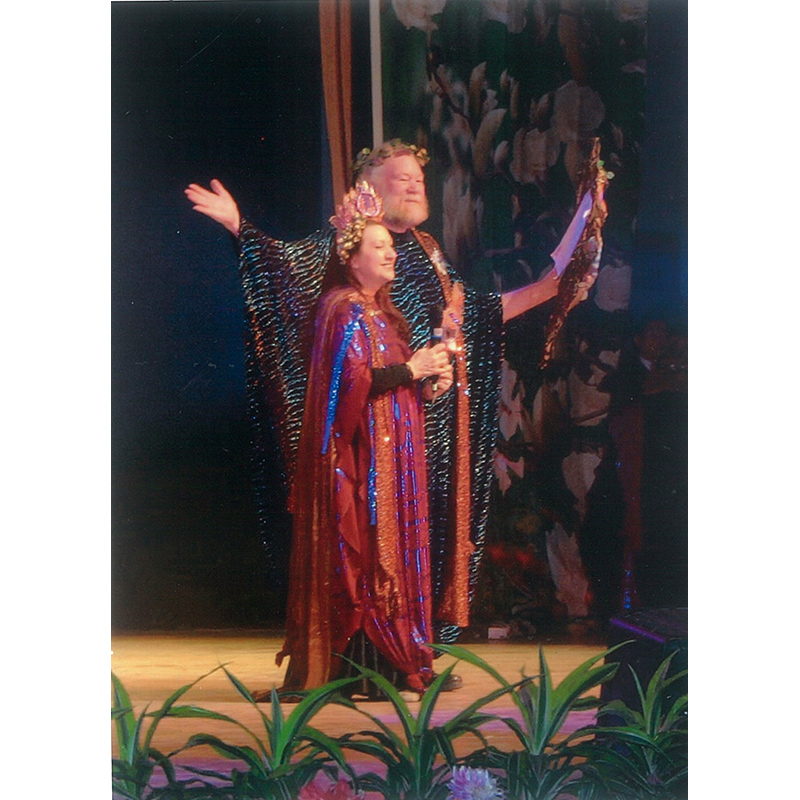

For answers, I went directly to the source, dancer and dance poetry pioneer Natica Angilly, who cofounded the Poetic Dance Theater Company with her husband, poet Richard Angilly, in 1984. As a choreographer, Angilly marries the classical aspects of ballet with abstract, emotive expression and ideas culled from a variety of non-Western schools and cultures. In poetry, and in particular in Richard’s writing style, she discovered the perfect vessel. Devoted to dance and verse, not to mention their own marriage, the two have been performing together ever since.

—Jen Karetnick for Guernica

Guernica: What is the raison d’être of dance poetry as a genre?

Natica Angilly: Under the Influence of Dance and Poetry is a title of one of my books, filled with specific dancers and poets, and it speaks about influence and honor. The title phrase fits my own search for something motivating, significant, or just plain fun. Making moves, attitudes, and environments designed toward a “connection” with the audience, other dancers, and with myself engages my entirety—my whole sense of being.

Most dancers, poets, and artists, including myself, are always looking for this core of understanding and consider this the “big” find, goal, and challenge: to speak with ourselves. We are all audience. Our human identity has been described as atoms dancing, a living poem, a moving message, and sometimes collectively, as in the title of one of my husband Richard Angilly’s poems: “Children of the Universe.”

Natural, developed, and studied efforts to share our singular and group experience are worth pursuing in all expressive languages, especially dance and poetry. The old philosophy that “the body does not lie” [motivates us] to create dance languages that speak with and to our humanity. The dancer integrates “reason of message” by becoming one with the language. The senses take this opportunity to venture into the personal and universal beyond, and strive to take everyone along with them.

Guernica: From where do your philosophies about dance poetry stem?

Natica Angilly: My own “peak moment,” which lit the path to poetry and dance as a unified art form, happened when I left the stage after my performance at the First World Healing Convention held in Northern California. This conference was designed to address integrated health practices for personal and community development with integrative cultural exchanges and an East-meets-West overview.

I could picture in my mind’s eye many dance moves that seemed to answer the words.

I had been working with industries that hired teachers who might help direct, broaden information, and offer moments of brightness and solace in the workplace. I met professors of literature, cultural and spiritual leaders. My choreography encompassed the consequence of evolving energies.

There were many waiting in line to congratulate me on my work [afterwards, and] the poet-in-residence handed me a package of papers. The papers were poems that made a very unexpected impression on me. I could picture in my mind’s eye many dance moves that seemed to answer the words. My own eclectic dance experiences and a generous knowledge of historical dance legacies inspire[d] future consideration [and] ignited my imagination. As I read each poem, clues to moves seemed to merge and emerge from the words and phrases. I went to find the poet, Richard Angilly, who wrote them. He lived at the Internal School—a division of the conference on healing associated with Humboldt College—and helped to manage the school. I told this poet that I could dance his poetry.

Guernica: Why did you go from dancing as a solo artist to founding a company based on dancing poetry? Did it have to do with Richard? You’ve said that you asked that he marry you on the spot, as soon as you met. That’s a little spontaneous, no?

Natica Angilly: Oh, yes! [It was] the most spontaneous, surprising, and life-changing event! Certainly an immediate connection was made. It seems that reading Richard’s poetry is and was the most pivotal discovery for me and it proved to give credibility to the transformational qualities of art. But the term “love at first sight” does not come close to my completely unexpected reaction to this unknown writer of words. I was not a shy person but acted with a healthy amount of care and deliberation all of my life.

As a single woman dance instructor and performer, I prided myself on the practice of thoughtfulness. Everything about this “adventure” was way past any usual behavior for me. However, Richard and I both seemed to feel a sense of depth, trust, respect, and wellbeing in each other’s company.

My immediate request to be married may have been a little unusual but met no resistance. All were very happy for us and the first of our multiple weddings to each other took place right away. From that moment, we became the poet and the dancer on a mission to bring active, visual integration to the realms of poetic language. Our search to discover, coax into performance, and become one with the intentions of the language of the poet became a partnership of development and collaboration. We were welcomed to perform at conferences, performances, memorials, house blessings, auditoriums, cathedrals, classrooms, international events, weddings, and gardens.

Poetry [has the ability] to define cultural temperament, carry the soul, share the spirit, and influence the heart. This was our work: the pairing of words and motion to create an appreciation for both forms that honors and contributes to cultural understanding and attempts to pass beyond the surface of conversation. At our second international World Congress of Poetry held in Morocco, a wonderful French poet said, “You are the perfect marriage of poetry and dance.” After thirty-nine years, we are still working with this universal language…as a unified art with unlimited outreach.

Guernica: How, specifically, did you form the troupe and evolve the program? It seems your reputation spread quickly and that you received many invitations to travel abroad and perform at diplomatic functions.

Natica Angilly: The dance company began with some of the students I was working with and several are still performing with the company as charter members. Community involvement is welcomed and diversity encouraged. Soon we attracted more students to join us. Dancing poetry is a full experience and engages the wholeness in the artistry of being. Poetry is more of an integral part of many older cultures and is considered a necessary skill in some.

Our first encounter was [made possible] by an invitation by the emissary to the king of Spain, Justo Jorge Padrón. He was visiting here in order to invite poets to a poetry event to be hosted by the king, who is himself a poet. Stanford University was the designated host for this international dignitary, but their arrangements fell through and Richard and I were teaching the unity of poetry and dance at Artists Embassy International (AEI) when the organization agreed to welcome and make receptions for the poet.

AEI arranged for many poetry organizations to feature the poets. We made our gallery, theater, and ballroom available for open events that highlighted the visitor. Our ambassadorial skills and our performances [resulted in] our first international invitation to the Ateneo in Madrid. One of the established Spanish women poets who traveled with us was overwhelmed with the joy of “opening” there, as this was the first time the doors were opened for women.

The treaty on whale protection had just been signed and we performed many poems, including “Dance With Whales” by poet laureate Mary Rudge, who traveled with us on our first international arts journey. “Voice,” written by Richard and visualized with my dancing, was a most appropriate opening that gave an inclusive welcoming to the event.

It was an encouraging time for active international arts exchanges, good will, and artistry. We were subsequently invited to other national and world events. For years Richard and I worked as The Poet and the Dancer, but by 1984, when we started to receive invitations to tour nationally and worldwide, I invited my dance students to join us in our new venture, The Poetic Dance Theater Company.

The Congressional Record contains a quote that speaks of poetic dance as the mother tongue of the world.

Getting ready for our trip to Morocco [in 1984] we received this letter from the governor of California, which contains this quote: “…the opportunity to present poetry in dance which overcomes all language barriers is one to be cherished and encouraged. I commend your skill and ability and offer my congratulations.” The president of the World Congress of Poets in Morocco, Leopold Senghor from Senegal, after seeing our performance, told us that in Africa, poetry and dance had never been separated. The Congressional Record contains a quote that speaks of poetic dance as the mother tongue of the world. We received this vote of confidence before our first international invitation from the king of Spain in 1982.

Guernica: How did you get started in dance?

Natica Angilly: Before the age of seven I embraced a love of dance. I was lucky that my uncle, Oliver Kostock, was a dance teacher for and with Hanya Holm [a founder and choreographer of modern dance]. He later served as director of the dance department for the University of Illinois. I was introduced regularly to visiting dancers on international tour and in shows. My family saw them as the dignitaries of dance that graced us with their presence.

Ballet, modern, ballroom, flamenco, international, and world dance whirled their way into my heart. From performances, classes, and friendly exchanges with our dancing visitors, I [learned] about technique, nuance, and the qualities of expression. I even learned that in the dances of India, more than 150 eye gestures are studied in order to communicate the essence of the dance.

Guernica: What, in a nutshell, makes a good dance poem?

Natica Angilly: A poem that communicates, engages, suggests, and moves the dancer. Something to dance for, with, to, and about. A poem that you can “see” dancing.

Examples of the grand-prize dancing poems as well as selections of nationally and internationally performed works that attracted us, or that we invented, are written and pictured at DancingPoetry.com [the website archive for the dance festival]. Each [poem] pictured and listed there was appreciated by live audiences of different and similar interests. Each poetic offering brings forth a distinctive persona of its own. Each shines with its own poetic identity.

Some of the poetry selections are very moving. The dance, working in partnership [with the poem], strives to be able to move with what is perceived as the poet’s intention. A great relationship of words and motion is imperative, and content and pictorial [visuals] are vital.

Guernica: I’m sure it varies in relation to the source material, but what kinds of movements and facial expressions are you generally drawn to as a poem-dancer and choreographer? Are there set pieces that always communicate relatively the same meaning to an audience?

Natica Angilly: I was compelled to write a little pocket guide, Facial Expression for Poetic Dance. Many have said they carry it with them in their dance bags and review it often. The book is based on what seems to me to be an excellent starting point of poetic expression. Nine exercises that help with understanding the focus of the face are easily personified.

I categorized “signature moves” and poses…. Easy to understand gestures revealed themselves. I recalled the one single dance gesture that defined the state of women that Hanya Holm choreographed for the race scene in My Fair Lady, and of course I recalled Isadora Duncan’s expressive pictorial of becoming a fountain. She defined refreshment itself in her explosive-looking move that seemed to demonstrate the freedom of spirit, flow of intention, victorious personal reach, achievement of heights and hopes, joy of sharing, and a gratitude toward life in one easily communicated snapshot.

Facial expressions—heroic, ethereal, inspired—are encouraged with little mirrors in hand to “test our success.” It seems to work to get things started and is lots of fun.

An amazing outcome from the performances is that poets want to choreograph, dancers want to write poetry.

Guernica: Why is it important for an audience to see and understand this visual medium?

Natica Angilly: Language accumulates benefits from the collaboration of word and motion working together. An amazing outcome from the performances is that poets want to choreograph, dancers want to write poetry, and many take away a greater sense of how they too might express themselves.

The “job” of the artist is to infuse, make contact, touch, connect. This is a primary reason for the timeless endurance and continual practice of all the arts. These qualities are particularly well served by poetic dance.

Guernica: How can dance poetry pave the path toward people becoming multicultural, multi-lingual, and multi-literate?

Natica Angilly: Intercultural dance and poetry, literature, film, photography, paintings, performance, readings, events, exchanges, and more share the languages of expression. [By] creating a visual medium for engagement and outreach, [we] create an opportunity to experience the “big” or “bigger” picture. When we experience feeling and when we create a context for deeper understanding through exchanges of creativity, opportunities for inclusion become more available. The poetic dance, and attempts to create poetry for dance and dance for poetry, is an engaging and well-lighted path toward citizenship in understanding the essence of culture and the experience of life.

It is said that the heart of any culture lives in its poetry. Poetic dance opens space for everyone.