Joe threw the flashlight’s hollow beam over the cabin’s walls. His heart thumped hard against his ribs, and he still felt hungry, though he’d eaten on the road—he felt weak. They had shown him he was weak. He circled the flashlight over the cypress ceiling, the weeks of dust on the mantle, the sweating floor. Through the open window, a lightning bug entered, softly buzzing. Joe’s knees buckled. He slumped down against the wall.

Nothing you can do, man.

The flashlight was heavy in his flaccid hand, and the light tunneled in the thigh of his waders, still outgassing their rubber fumes—not a speck of mud on them. They’d trained their guns on him and they’d won.

Alright. Nothing I can do, nothing I can do.

He’d let them back him down.

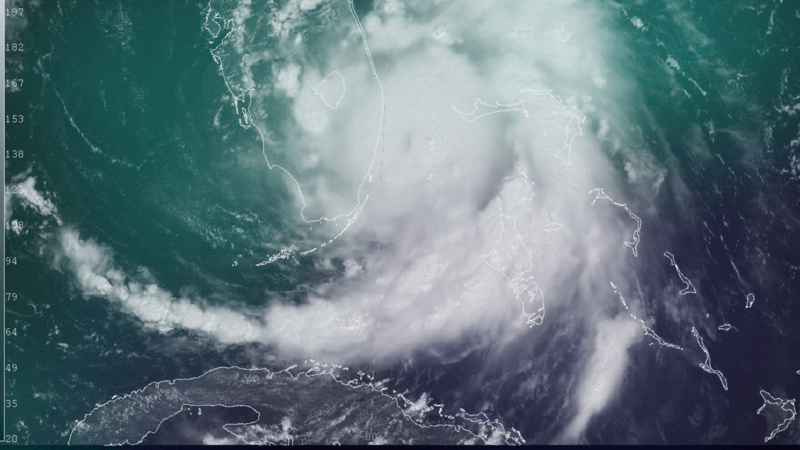

All around the lake, through the old circle roads barricaded with fallen trees, he’d picked his way. He saw what the storm had left: a gator flipped on its back, showing its pale belly. A wild boar with a shredded coat, hung by its tusks from a tree. Shards of bridges, whole houses floating on water.

Men with guns were stationed at the entrance to the twelve-mile bridge. A corn-fed black kid from Iowa had wrinkled his brow and nodded, listening, then shaken his head.

Nothing you can do, man.

But my daughter’s in there, Joe said.

You have to have faith—

Faith? He’d laughed, before looking harder: The uniform starched and shiny. The cross tattooed on the side of the soldier’s neck. You tell me what you have faith in. You believe in God? You trust in the goddamned government?

The boy just blinked.

They’d shoot you as soon as look at you, son, Joe said, and that was when the other soldier shouldered his rifle and he realized he had Vin’s 9mm in his belt—all among the Humvees, the click-clack of rifles brought to ready.

Joe clicked off his flashlight. The pain in his belly roared like a wood fire, and he let himself fall to his side on the rag rug. Pain traveled through his back, up into his chest. It licked the spaces between his ribs. The tree frogs singing twilight stopped abruptly. Breeze came through the window with its cargo of water, and he could almost feel his mother’s hands, soothing him to sleep.

A hard-bodied insect landed with a click. He pushed himself up off the floor. He picked up the flashlight, his bag from the counter, picked up the pistol.

The moon was no more than a fingernail clipping, and the shadows of things identified themselves only by their sounds. Wind whipped through the batture trees, while generators roared beside the whisper of clapboard shacks and revenant dovecotes. Warehouses lumbered toward him then retreated until their noise merged with the river’s sibilant hush. Every now and then a bird cried out, and he fingered the safety of the pistol in his lap. As the stench of the rotting city rolled up toward him, overtaking the sharper smells of swamp and sulfur, he thought of the sentries, what he’d do if they stopped him again. My daughter’s still in the city. You have to let me in. He saw himself pounding on a huge steel door.

No cars passed, no helicopters, and he imagined he heard breathing—people hunkered down behind their barricades of fallen trees and locked doors, tossing in their sweaty beds. They were waiting for someone to come up from the city and drive them at gunpoint from their homes. The pick-ups and old sedans they’d parked nose to nose across the gates of their suburbs eyed him as he passed.

When finally, up ahead, he saw a Humvee hunched on the shoulder, its lights off, he steered the truck slightly left and shifted it into neutral. The sound of the tires rushing across asphalt mirrored the surge of the river. He unsafetied the pistol and glided, waiting, but the Humvee didn’t move. Beyond the levee, flashlight beams played in the mossed canopies of the trees.

The tree frogs shrilled like sirens. He shifted the truck into drive and pressed the accelerator to the ground, feeling the cold sweat prick up on the back of his neck as the speed threw him against the seat. He was on the inside now, one of them, and as the humid stench of the city grew denser, he felt fear like a huge black bird descend upon his shoulders and dig its talons in.

He followed the river through its bed, over the train tracks at Magazine and into the wet heart of the park, had to inch the truck around limbs fallen from the big oaks. He veered back out to rejoin the river at Tchoupitoulas, where the warehouses and gray wharfs lengthened into the night, wharf upon wharf upon wharf, and the shotgun shacks of long dead longshoremen crouched, their chimneys choked by alligator vines laughing in yellow bursts of flower. His eyes began to close. He opened them with a start to see only the endless gray wall that protected the river from the city, protected the city from the river so well that the sound of the water could not reach him. He knew the river was there, though; he felt its flow like the moored ships must feel it, their heads bent like beasts of burden against the current, their bodies brushing against the endless walls as they slept.

His bumper scraped against the port wall, and he woke and did not know how long he had been sleeping, the truck carried downriver like a raft. The wall went on with only short interruptions all the way behind him to Napoleon, all the way in front of him to the Industrial Canal, as these houses alongside went on. He could not see the light-spangled bridge either before or behind him. The dark bird unfurled its wings and folded them again across his eyes. He could see nothing. He could not stay awake. He was home. He did not know where he was.

In New Orleans, Tess would have been able to place the man right away. Jesuit, a few classes ahead of Joe. But here in Texas, she could only smile as he put his hand on the back of her chair, his tie riding out over his belly.

“Fancy meeting you here,” he said, as Augie stood and shook his hand, still chewing his mouthful of bread. Tess extended her hand, and he took a weak hold of it.

“John Gunten,” Augie shook his head. “Well, aren’t you a sight for sore eyes.”

“Augie,” John said, still looking at her. “I was about to say the same thing. Literally: a sight for sore eyes. If I’d have know I had to come to Ruth’s Chris, Houston campus, to find you, I’d have been flying out to dine here twice a week.” He laughed and jutted his chin at Tess. “Is this the pretty young thing you’ve been hiding away from us?”

“John, you know Tess Boisdoré,” Augie said. “Née Eshleman. Joe’s wife?”

Tess smiled and shook her head. “John, always with your jokes.”

“Tess, I beg your pardon.” John closed his eyes hard, opened them. “But, good heavens, hasn’t it been a while? I tell you, it’s like discovering the lost Atlantis of New Orleanians, coming to this place—” He turned to the dining room, adjusted his tie. “We have the Willses,” he said, peering toward the back corner of the restaurant. “The Godards, a pair of Youngs with the Edgar Vowells.” From a large roundtop, a woman in silk leopard print waved, and John continued, “The Vowells, if you hadn’t heard, were planning a move here in October. Closed on their house last Monday. So, now, apparently, they’re running a regular Red Cross. Nina was just telling me she bought the Target on San Felipe entirely out of air mattresses.”

“Heavens,” Tess said.

“Have you heard about—” John paused, pointed at her. “You’re where?”

“Esplanade and Royal.”

“Excellent.” He nodded. “Good and dry. And I saw Augie’s place on television.”

“You did?”

“Looks like it’s standing up fine.”

“I’d heard. The Katz’s called earlier today.” Augie nodded. “All’s well on the natural levee.”

John was shaking his head. “Aren’t we lucky.”

“And you, John?” Tess asked.

He shrugged. “We’ve got oak limbs down, but I think we’ll be all right. Worried about the refrigerator, though.”

“Oh, best to accept that loss now.’”

“’The boys have been lobbying for ice through the door anyway,” John shrugged.

Tess picked up her fork and held it, smiling, beside her martini glass of crab salad.

“Listen, I’m going to let you get back to your meal.”

“No—” Augie said, though he sat down, resettled his napkin. “Please.”

John patted him twice on the shoulder. “Augie, Jack Lampert’s got a tee time Sunday at River Oaks. You’ll remember him—Exxon Mobil, used to be Shell. It’ll be me, Jack, Edgar Vowell. We need a fourth.” Augie opened his mouth as if to refuse, but John replaced his hand on his shoulder, closer this time, to his neck. “I won’t take no. We’ll borrow you a set of clubs.”

Augie laughed. “Alright, John.”

“Alright, then.” His hand lifted from Augie’s shoulder. “Tess.” He nodded her way and weaved back through the dining room, toward the new wife and the four blazered boys.

“Everybody had the same idea, it looks like,” Augie said to her.

Squeezing her eyes tight, Tess nodded. She shouldn’t have come. With John gone, the worry flooded back in. The windowless dining room kept giving her déjà vu: the low ceilings reflected the smell of beef fat and browned butter back down upon them, and she kept forgetting they were not in New Orleans, then remembering again.

“I wonder if Joe has checked in yet.”

Augie nodded. “He’ll find her. You know he will.”

“When I called you, I swear—”

“I know, Tess.”

“I’m sorry I was such a wreck.” She shook her head. “Good of you to stay at the Four Seasons. If I’d had to go farther down the phonebook, I don’t know what you would have thought when you picked up the phone.”

“You needed to talk to somebody, I needed to talk to somebody.”

She had gotten dressed. The empty afternoon, something to do. All around her, the Vowell women, John Gunten’s wife, were also in their best—they had all taken their going-out clothes along with their three pairs of underwear. An evacuation vacation, it was supposed to be. She had shaved her legs. Lain in bed with a cold washcloth over her eyes until the puffiness went down.

Augie nodded heavily over his bowl of bisque. “One cannot live on news alone.”

“You haven’t been able to raise your mother?”

He sipped soup, shook his head.

“But the Katzes spoke to her, you said?”

“They called from a payphone in Monroe. She wouldn’t go with them, said she ‘had guests.’”

Tess cocked her head, knit her brow. The last time she’d seen her, Mrs. Randsell hadn’t recognized her at first. She was locking her car on Prytania Street in front of the cheese place, bag on her arm, hair freshly done.

“No, no,” Augie shook his head. “She’s sharp as a tack. Rhoda said there was a Jeep parked in the driveway with a boat tied to the roof. ‘A nice colored couple gave me a ride,’ she said Mother told her.”

“Cora,” she said, and she felt her fear pop, like a balloon pricked with a pin.

“No, surely—”

Tess nodded. The balloon, emptying, sped wildly around her heart. Her brain was repeating: a Jeep, Cora’s Jeep. “Yes! Cora and Troy. Joe spoke to her night before last. He told her your mother was stranded on Northline. They must have gone to fetch her.”

“Cora.” Augie took a deep breath in, nodded. “Cora. Do you think, really? God bless her. I would kiss you—Cora!”

She felt her face flush. Augie’s thin pink lips closed around the bowl of his spoon. His long fingers reached out and cradled his glass of Châteauneuf-du-Pape, raised it.

“Good news for us both, then.”

She left her wine on the table. “I don’t know, Augie.”

“No,” he said, his wineglass still raised. “Undeniably. Good news for us both. They both made it through the storm okay. They’re both fine. And Joe’ll be down there now. I bet they’re having a barbecue. Steaks in the freezer will still be alright.”

Tess laughed once and touched her wineglass to his. “It’s a nice thought.”

Augie nodded.

“I still, though—” She fished around in her martini glass for the last lump of crab. “It’s a fucking war zone, Augie. And she’s been tooling around in a boat? No. And I hate to tell you, but I don’t feel good about your mother alone in that house in the heat, either.”

Augie sighed and leaned back, a hand against his chest, while the waitress cleared his soup plate.

“Baby steps, Tess. Let’s just be glad they’re probably alive, okay. Besides, what can we possibly do about it now? We should have our dinner, try to enjoy ourselves.”

“No,” Tess nodded. “You’re right.” She arched backwards from her chair and waved at the waitress before she disappeared again. “I’ll have a glass for the red now, please?”

“Oh, good,” Augie said. “You’ll like it. It should hold up very well to the steak.”

The bus boy returned with a wide-bowled glass, and Augie poured for her from across the table, twisting the bottle when her glass was half full. She lifted it to him, then buried her nose in it and closed her eyes, breathed in deeply the smell of cherries and pepper. As she told her patients, it was possible to escape your anxiety: you observed yourself without judgment while focusing on the minutia of the present, then you chose the best path forward. You told yourself Now. Now. Now. Now. Now. Then? and if your heart was still racing, you went back to the Now. Now. Now. Now. Now.

“So, explain it to me again—Joe needed you to stay here to look after his father?”

She shook her head, her eyes closed. “I thought we were supposed to enjoy our dinner.”

“Well, what shall we talk about then?”

She opened her eyes, and he was leaning over the table toward her, a lingering scent of his aftershave emerging through the smells of beef and wine. She had always loved his nose, the way, halfway down, it dipped then rose again, like a curtsey. Since 1966, she had been stopping herself from wanting him, but she did not have the energy now. Here they were, alone and cut off and useless, except to one another. She placed her hand in the middle of the white tablecloth. He put his hand on top of her hand. The waiters arrived with their buttered steaks and Lyonnaise potatoes, they cut their meat, drank their wine, their hands found each other again. The beef, corn-fed, dissolved on her tongue, and John Gunten came back through the dining room, clapping men’s shoulders, kissing the women’s cheeks.

“Don’t get dessert,” he said. “I’ve just heard they’re moving corporate to Orlando.”

“Ruth’s Chris’s? Already? Can’t even wait for the body to be cold?”

“Ruth would never have even considered it.”

“It’s disloyal is what it is. Shameful. Kick us while we’re down.”

They watched John leave, past the lobsters crawling over one another, waiting for death. Tess cut her meat. She could think of nothing to say. Her hand went back to the center of the table, and Augie again put his hand on top of her hand.

A man was rapping on the hood of the truck when Joe awoke. He lay slumped across the chiming console and curled around the gearshift, still set to Neutral, and the windows were open, his skin filmed with dew.

“You’d think,” the man said, a tall man in a tucked-in polo with an ID tag around his neck, “you would think that sleeping wrapped around a 9mm would be safer than the alternative, but I’m afraid to tell you that, on this particular day in this particular place, you’d be dead wrong.”

Running his tongue across his teeth, he blinked at the man. Behind his looming head, the sun seemed too high, too hot, too yellow. His truck was parked in front of the Walmart that had been dropped into the middle of Irish Channel like a bomb, and just blocks away, the twin spans of the Mississippi River Bridge vaulted out of the city. They had been invisible the night before, of course, the power out.

“What time is it?” He was surprised by the sound of his voice—gruff, hard-used.

The man smiled a goofy smile. “You late for brunch at Brennan’s?” He looked at his watch. “It’s quarter of nine.”

Joe licked at the scum on his teeth. “So, I’m free to go?”

“Who am I to stop you?”

The man laughed. He put a hand on the window frame and leaned in so that his laminated badge dangled in front of the steering wheel. “FBI” was written in large capitals across the top, and Joe felt his guts loosen. He lifted his hand off the gun.

The man, however, kept smiling his goofy smile. “You want to hit that ignition? I can jump you if you ran your battery down.”

Joe pushed his foot into the brake, turned the key. The engine turned over fine.

“Good, good. Now, last question: You well-supplied? You need any water, MREs?”

“I’ve got water, thank you. And I’m heading back out this afternoon.”

“Leake Avenue?”

Joe nodded. “River Road.”

The agent’s eyes crinkled up, and he beat the hood again twice, then stepped away. “Well, don’t let me interfere with the conduct of your business.”

Before the agent could change his mind, Joe tore out of the parking lot. In the rearview mirror, the agent just kept standing, smiling, his hands in his pockets, until Joe lost him behind the buildings.

In the daylight, the city had regained its geography, but not its sense. People sitting on their porches looked up to watch him pass. Torn power lines, shingles, broken glass, trash cans, fence boards littered the sidewalks and the streets. A pair of women picked their way through it, burdened with trash bags and bundled blankets.

Even before he’d left the underpass’s shadow, he saw them: people pouring out over the sidewalk in front of the convention center, spilling off into the street. He shifted into the left lane to avoid the crowd, then shifted back. Cora wouldn’t be there, but she could be, amid the men and women crouched on the curb, sitting on coolers, cradling tiny white-clad babies against their chests. No—she would have gone away again if she had come, wouldn’t she? On the neutral ground, an old man slumped over the arm of a woven lounge chair, completely still. No. A news camera was wading into the throng, trailing wires back to its van. People surged toward the camera, the microphone. People backed away. Hands shot up, drifted in the air. Shouts sounded, rapid-fire. A woman sitting on the curb pointed up at him, and her child, a little shirtless boy, came running. The woman followed, and then others—a large man in LSU sweats, a tiny girl in filthy flowered pants—wandered up to the truck, knocked on his windows. They beat against the metal, the windows. He kept his foot on the gas, a gentle pressure. He put his head down. He didn’t understand. He wouldn’t understand. He laid his elbow into the horn, and when the hands left his truck, he kept driving. In the rearview, the woman in the shirt dress dropped to her knees in the middle of the street and pressed her head to the ground.

On Esplanade, Joe saw no sign of Cora’s Jeep. Still, he parked and ascended the steps, looking up at the house’s high pediment careening against the sky. Beyond the front door glass, the foyer swam in dim light, the pine boards playing in the faceted sun. As he unlocked the door, he saw Cora’s iron bear crouched on the front stairs, her paws raised up in menace. The doors closed behind him, jangling the house, and the silence sealed itself.

“Cora!” he called out.

He heard his voice bounce back at him from the high ceiling of the stairwell. From the kitchen came the sound of wind in the leaves.

He could hear that the house was empty. It was like a musical instrument, its resonance changed in the presence of a body. As he climbed the stairs, the risers crackled. He ran his hand along the bannister—the velvety, oiled wood.

“Cora!” he called again.

In her room, the sheets had been pushed off onto the floor. Her big suitcase sat on top of the bureau, clothes falling out of it, and her nightdress hung over the back of the cane chair. He picked it up, crumpled it in his hand, brought it to his nose. It smelled like her laundry detergent and her sweat. He crossed the rug and ran his hand across the mattress, cool after the hot night just passed. In Del’s room, too, the bed was unmade, and the man’s reeking laundry was piled in the corner. He went from bathroom to bathroom, the tubs all still full, though the one in the front, which they must have been bathing in, was cloudy, and wet towels hung from the racks. At the end of the hall, the door that separated the front of the house from the back had been blocked by one of the guest-room sleigh beds, turned on end, and he turned around and went back downstairs and into the library. They’d arrayed their provisions on Tess’s desk—bread, peanut butter, jelly. He picked up a crumb and squeezed it. Still soft. They couldn’t have left more than two hours before and they wouldn’t have been planning to go far, without their things.

He would wait, then.

Cora and Troy had pushed the heavy mahogany server from the dining room in front of the door to the kitchen, and Joe had to wedge himself between it and the wall, and push out with his legs to get through. Just as Cora had said, the magnolia tree had fallen through the ceiling. The trunk rested on an upper-floor joist, but the lower trailing branches crept in across the floor, littered all the way to the counter with broken glass and plaster, browning leaves and seed cones. A rain of debris had settled in the branches, where a few blossoms still clutched their stems. Their sticky-sweet perfume mingled with the smell of damp heat and early rot.

He thought of the old man on the neutral ground, slumped over the arm of his chair. He looked up again and the sun glared across the shiny tops of the leaves. The tree was nothing.

Out on the street, he heard a car pass, and a gust of wind rattled the leaves. Someone pounded on the front door. Joe, already still, felt his joints lock up. Even if she’d seen his truck out front, Cora would not knock. It would be the stranded, then. Or looters. Or the police. They pounded louder, once, twice. He heard the latch break through the door with the sickening sound of splintering wood, then the tramping of their heavy, mud-caked boots across the floor. Police. He stood still inside the branches of the tree as they made their way through the house, one hand on his wallet, one hand on the gun tucked into the waist of his jeans.

Tess let the stupid pay-as-you-go cell phone drop from her hand onto the pool deck. It hardly mattered if it broke—she couldn’t get through to anyone, not Joe or Cora, not Augie, not even Del, who was in New York and should damn well be able to answer her phone, but no, she was extraneous, Tess. Useless. Zizi wouldn’t even let her clean the goddamn kitchen cabinets. Instead, she had scooped her a quart-sized sippy cup of strawberry daiquiri from the tub they apparently kept permanently in the freezer and sent her off to the pool to Relax! The truth—and she had to acknowledge it—was that she was not even wanted.

She would try to relax, then. Observe yourself without judgment, focus on the present. She breathed in, breathed out. A bird peeped somewhere to the right of her, in the bushes that surrounded the pool. Peep, peep, the bird said, but she couldn’t see it—a female, maybe, camouflaged in her dun-colored feathers. She should recognize the long, fluty peep. After all, she was not far enough away from home that the birds should be different. Even the people here were of the same species—seafood people, shipping and oil.

You couldn’t blame Zizi for wanting her house to herself. They were all on edge. Her head throbbed from the Côtes du Rhône, and Vincent had not slept well the night before, padding up and down the basement hall, mumbling to himself. He kept taking off his Band-Aids. Zizi had not even gotten dressed. She had driven Kevin to school in fuzzy slippers, and then she had taken charge of Vincent, sent Tess off with her daiquiri. Gotta liquor her up, Tess imagined her thinking, make her easier to deal with. No, she was doing her best, and Tess shouldn’t have gone off on her in the grocery yesterday, but she was doing her own best, too. Marriage was supposed to be an institution of mutual support, but she had been left behind, considered extraneous. Joe always thought that Cora, Daddy’s little girl, would respond best to him, no matter how many times she proved him wrong. On the news this morning, there were buses lined up outside of the Superdome, and dead people in wheelchairs at the Convention Center, but he’d had to go down there alone. Perhaps he was only trying to spare her: Keep her from having to see it first hand. Keep his darling wife from going to jail. He assumed, perhaps, that she wouldn’t like the heat.

The heat was no different here, though, the sun pouring mercilessly down. It had slipped from the apex of the sky and crept under her umbrella and onto her bare shins. She pulled her legs in and rubbed on more sunscreen, then got up and tilted the umbrella to face the lowered sun. She’d heard somewhere that the pronunciation of the word “umbrella” was the only common, distinguishing trait among all of New Orleans’s accents, the only word that Yats and Uptown girls and Creoles, men raised in Garden District mansions and girls brought up in the Desire Projects, said alike. UMbrella—the FBI listened for it on wiretaps or the CIA or whoever in their closed interrogation rooms. Don’t try and tell me you’re not from N’awlins. UMbrella—the one thing they all had in common, incessant rain or humid shine.

As she was trying to settle herself back down onto her chair, the pool gate opened, and a woman came through, herding her children—twin girls and a boy—and raised her hand in greeting.

“Afternoon,” Tess said, but her brain still repeated UMbrella, umBRELla, UMbrella.

The oldest of the children, a red-headed boy, cannonballed into the pool while the woman pushed the girls toward the lounge chair at the other end of the short row. Tess watched the bubbles pop as the boy sank to the bottom like a stone.

“Oh, don’t worry about him,” the woman said to her, sitting down. “He’s been whining all morning that his sisters won’t give him any space—” The woman chuckled.

Tess smiled and nodded and picked up her book. She had failed to make any headway at all so far, and now over the edges of the binding crept the familiar creak-squeak of water wings scudding up sunscreened flesh.

“I hope we’re not invading your peace,” the woman said. She had finished with one girl and was moving on to the next, the blue floaties pinned between her knees.

“Oh, no.”

The boy was motoring now in the direction of the shallow end and away from the freed twin, who screeched as she padded toward his end of the pool, her arms locked in the teeth of the shark-shaped floaties. When she jumped in at the deep end, her brother immediately climbed out, retreating to the edge of the enclosure, where he began thrumming his fingers over the fence. Tess couldn’t say she blamed him. The second sister was trying to wriggle away from her mother as her arm was yanked through the second float.

“You have kids?” the woman asked her, setting the second twin free.

No, Tess’s brain said. She wished she could lie, but the woman was leaning toward her, the belly that had never recovered from pregnancy hanging over her thighs, and Tess realized it was already too late to lie.

“Yes,” she said. “But they’re grown.”

“What a relief that must be.”

No. Tess picked up the cellphone from the pavement, watching the boy break a stick off a bush. No, when they were little, Cora and Del, they’d been in her control.

“Here in Houston still?”

“No, we’re just visiting,” she said and realized immediately she’d made a mistake.

“Where from?”

She laid hands on her book, but she had to answer and answer honesty, in case the woman showed up later at Vin’s. “New Orleans.”

“Oh, God, no,” the woman whispered. “No, no, no. I’m so sorry. Is your house—” She made a face. “Your family?”

“Fine,” Tess said. The little girls were splashing each other, their chubby legs kicking at the eight feet of blue as their wings kept them safely above water. “Fine, fine, fine.”

“But you must be devastated.” The woman leaned over her thighs, her deflated breasts pressed in their spandex. “We know so many people from there. My husband works with at least eight at Shell—people who are safe and sound here, and all their relations have come to stay, and they’re just packed to the gills and glad to be, but nobody’s really fine. How could you be? I can’t stand to watch the television and I have no connection at all.”

Tess opened her mouth, closed it, looking at the boy who was thrumming the fence now in its higher register. She wanted to snap that the woman should mind her business, mind her children, that she was the one here accredited to tell people when it was not okay to claim to be fine—with their city besieged and daughter caught in it, husband gone off alone to save her—and when it was, when “being fine” was the only fucking option, when if she allowed it to be otherwise, she would be the one circling the fence, beating on the bars like something caged.

She was trapped—no car, no husband, no home to go to. Trapped in Houston, yes, but not here inside this fence with these piranhas, obligated to make nice. She rose to go.

“I’m sorry,” the woman said. “I didn’t mean to bring up a difficult subject. I’ve ruined your afternoon. It’s just we’re all so sorry.”

“Thank you,” Tess said, but it came out sounding hard. “I do appreciate that.”

Off in the distance, scared away by the children’s noise, the little bird went peep peep.

“You must believe that I do.”

By the time they had pushed the buffet aside, Joe had decided to take the offensive. He had drawn Vin’s gun, and he held it, cool, at his side, as they pushed into the kitchen, four men in an unmarked uniform of dark khakis and bulging flak jackets, semiautomatics in their arms and pistols taped to their thighs.

“This is private property,” Joe said.

The man in front, a broad man with a shaved head, flicked at his ID badge the way you’d shoo a dead fly off a table. “Holster your weapon, sir.”

The troops resettled themselves behind him, legs together, closing ranks.

Joe liked the weight of the pistol in his hand, like a stone.

“And this is private property, I said. Do you have a warrant?”

“I would make you aware, sir, that in a state of emergency, the concept of private property does not apply.”

“It’s not a concept.”

The mouthpiece curled his upper lip. “What’s your business here?”

“I don’t need business in my own home.”

One of the younger men bounced his rifle against his hip. The mouthpiece held his hand out, palm up.

“Holster your weapon,” he repeated.

Joe slipped the pistol into his waistband, keeping his eyes on the men’s guns.

“Government-issued ID.”

The mouthpiece did not move. They were probably three yards from each other, separated by half of a tree.

Joe fumbled in his back pocket for his wallet. He had always known it would come to this—that someone, someday, would question his presence in his own goddamned house. He should have thrown it back in Tess’s face that day, her daddy’s money. Nothing had belonged to him since. The man would not move from his position, and as Joe pushed his way out through the tree, a branch, unbent, whipped him across the chest.

The mouthpiece took the license in two fingers and looked from the photo to his face and back again. He read out the address of the house.

“Are you aware that Orleans Parish is under a mandatory evacuation order?” He tapped the card in his palm.

“More than aware.”

“Are you also aware that we are authorized under the provisions pertaining a state of emergency to compel you to comply with this evacuation order?”

“Are you aware that there are hundreds of people standing out in front of the Convention Center who are just waiting for you to compel them to comply?”

The mouthpiece looked at him, flipping the license between his fingers like it was a playing card. It had clicked then, that he was no longer in the world he’d thought he built. That whatever he’d built, it did not belong to him: nothing ever had. He remembered the nightmares he’d had in college: The jackboots. The card inscribed with the date of his death pushed across a wide desk by his high-school principal. The rope a naked blonde woman had given him as a prize. He remembered the cold sweat, the plastic dorm mattress under the sheets, his heart beating. The girl he’d visited in Montreal who’d slapped him in the face as they made love, the dense hair on her legs like a man’s, the smell of frying sausages. He thought of the email Charlie Tolland had sent before Joe left Houston: stories of snipers posted on the roof of Poydras Home, shoot-to-kill orders, of the Jefferson Parish cops barricading the Mississippi River Bridge against the citizens of New Orleans, who, as in the old days, were not really considered Americans, who probably never had been.

“Am I a bus driver?” the mouthpiece asked him, finally.

“No, sir.”

“That’s right—” He looked down at the license. “—Mr. Boisdoré, I am not. I am under orders to compel you to evacuate. Will you comply, or do I have to compel you?”

“I will comply.”

“Good.” He held the license out into the air between them, but did not let go when Joe put his hand on it. “But first, is there anyone else on the premises?”

No—he thought of Cora out there in a boat on the flood, thought of her here, her hair in this man’s fist. He shook his head, and the mouthpiece let go of his ID.

They followed behind him as he walked back to the front of the house, close enough that he could feel the rifle butt to the ribs they would give him if he slowed. They allowed him to close the door, and then one of them shook a can of spray paint and drew an X on the siding, surrounded by an inscrutable code.

As he drove slowly away, he watched them move down to the Maestre’s house and knock once before they rammed a rifle through the door’s glass. The troops entered, but the mouthpiece lingered on Wynne and Susan’s steps, watching him. As Joe made a U-turn, he pointed a finger at the truck and shot, mouthing the sound of fire.

Lights jumped into the plate-glass window at the front of Vin and Zizi’s house, and, for a second, it didn’t register with Tess what this meant. She had slept two hours of sun-doped sleep and awoken to the sound of laughter. Kevin had won his baseball game, Vincent was punch-drunk. Zizi made such good snap beans, Vincent kept saying, so porky. He waved his knife like a baton. So porky—it made her laugh so hard she felt the wine in her sinuses. It was as if the world had been encased in a thin sheet of ice that had suddenly melted.

“You know why these beans are so good?” Vincent said, his face innocent.

“Why?” Zizi was trying her best to keep a straight face. She took a deep breath through her nose.

“Because they’re so porky!”

Kevin, who headed to the kitchen for seconds, laughed so hard he snorted, which only made him laugh harder. He collapsed onto the floor, his back against the island.

“What?” Vincent said, blinking. “You know there’s bacon in it.”

Tess sucked at her own mouthful to keep from laughing. They were fall-apart tender the way her mother made them; she could almost see the bowl left for her father’s dinner in the ice box, floes of congealed fat on its surface.

“So porky,” she said, swallowing.

Vincent crinkled his brow, lowered his fork. “Tell me your name again?”

The pressure in the room dropped. Kevin clanged the serving spoon against the pot.

“I’m your son Joe’s wife, Tess.”

Vincent blew wet breath between his closed lips and started laughing. “I see what’s so funny!” He pointed his fork at her. “That’s funny. She’s funny.”

For a second, she thought the lights jumping into the plate-glass window were the headlights of her father’s Bonneville—that chug-chug of engine. She dabbed at her lips, sat up straight. Then, the lights went out, the truck’s engine cut off with a rumble. Joe. She took a gulp of wine and stood, holding her napkin against her lap. Joe had gone down and come back in forty-eight hours, without stopping to call, which meant he must have gotten in, found Cora, gotten out as fast as possible. She imagined Cora hunched against the passenger door. Joe would not have wanted to leave her side, not even to use a payphone.

Vin was at the front door. He opened it, and she saw Joe’s head bobbing as it rose up the steps, but she heard only one set of feet—he must be carrying their daughter in his arms. Vin moved away from the door. Joe’s arms were empty. Vin stood on his tiptoes, looking out toward the car.

“Who’s this?” Vincent asked. “What’s wrong?”

Tess felt herself fly to the door, out of the door. It was how she flew in dreams—her feet did not feel the ground, she did nothing, felt nothing but the wind in her face, the pressure of the wind in her face.

“Tess?” Joe was calling her name, but she ran away from him. She ran as she hadn’t run in a very long time, not since she was a child, probably, running from It on the playground, panic-sped. He would not catch her. Her breasts in the lacy bra banged against her ribcage, she ran, and the yellow streetlamps crashed into her. Somewhere behind her footsteps, her breathing, Joe’s footsteps, there was a profound silence as though something had just imploded, like the grain elevator across the river in ’78. They’d thought it was a bomb, they’d sat up straight. The after-sound of the boom rang in their ears as a silence descended in which you could’ve heard the chaff floating down to earth if you’d know that there was chaff.

She was dead then. He had arrived, and the looters were in the house. They had tied her to a kitchen chair. Shot her at the door. He had arrived, and Augie was wrong: she was floating, facedown, in the garden. They had abandoned their daughter. They had let Cora stay.

Tess stopped underneath a streetlamp, her back still to him. She looked up at the lantern, painted green to look like oxidized copper, a glass bell for an oil lamp around the yellow bulb. Joe moved into the light, and his shadow fell across her. On her sleeve, the line of his neck stood out vivid and straight.

“Look at me, goddammit.” He was out of shape. He was panting.

She looked at him. She felt as though her mouth was glued shut to keep it from quavering. Joe sighed. The circles beneath his eyes were dark, almost maroon. He hadn’t slept.

“I couldn’t get in.”

*

Excerpt from the novel The Floating World, to be released by Algonquin Books in October.