On October 11, 2015, a freezing winter night in Kyrgyzstan, nine detainees mounted a spectacular escape from SIZO 50, a maximum-security prison on the outskirts of Bishkek. After overpowering and killing three guards, they dashed through the prison courtyard under fire from a sentry on a watchtower, smashed their way into an office along the perimeter wall, and snuck out of the complex through a window.

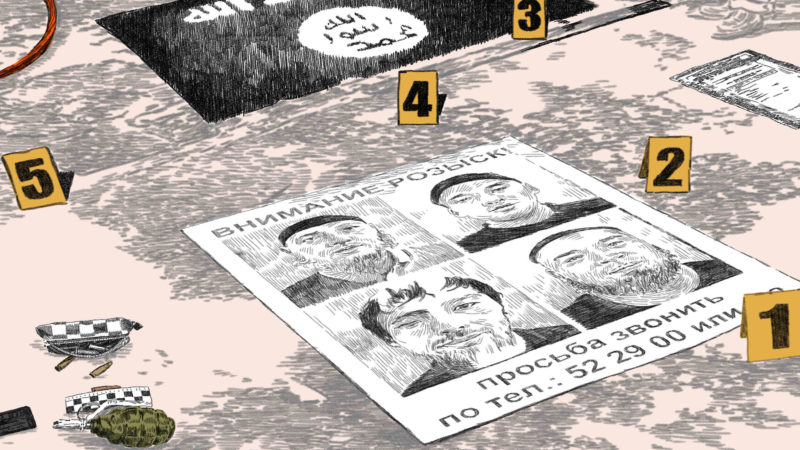

Five of the escapees were almost immediately recaptured as they frantically tried to find a hideout in the city suburbs. Police special forces with sniffer dogs roamed the city in search of the remaining four. Their photos were printed in leaflets and posted on bus stalls and inside trolley buses, encouraging citizens to call the police with possible leads. The manhunt featured in everyday conversations and countless media stories that described the men—a motley crew of detainees, some sentenced and some awaiting trial—as “especially dangerous criminals.” For days, the city lived on edge.

By the tenth day, three of the nine escapees were back in prison, three had been killed in the recapture efforts, and three had died in custody, all allegedly suffering from “heart attacks.” As the Kyrgyz authorities’ version of events turned ever more fanciful with each passing hour, however, claims that they were fighting terrorism appeared dubious. Washington was leasing an airbase in Kyrgyzstan that served as the main hub for US and NATO forces fighting in Afghanistan, while Moscow viewed the country as integral to its plans to re-establish its influence in Central Asia. The government was ready to exploit the rhetoric of the global war on terror (GWOT) to cling to power at all costs, while gaining international support and aid in the process. At different times, the United States and Russia were happy to oblige, depending on their own strategic interests.

ISIS in Kyrgyzstan?

According to the prosecution, the nine men had been planning the breakout at least since mid-September. Thirty-eight-year-old Altynbek Itibayev—a native of the southern city of Osh and the escape’s alleged mastermind—had managed to befriend one of the prison guards by offering to have his car serviced for free at a mechanic friend’s workshop. In exchange, the guard had started to allow the prisoners, who normally sat in three separate cells, to gather on the patio in the evenings to exercise. There, they had organized their escape.

The prosecution claimed that the detainees were planning to carry out terrorist attacks in Kyrgyzstan and then to join the Islamic State (ISIS) on the ground in Syria and Iraq. In case file n. 83-15-204, the prosecution stated that “the organizers of the criminal group were Edil Abdrakhmanov, Altynbek Itibayev and Daniyar Kadyraliev. The latter would periodically speak via mobile [on the] internet with ISIS recruiters.”

But the prosecutors offered little in the way of evidence to bolster these astonishing allegations, and the story put forth in the case raises more questions than it answers. For example, how would a mobile phone end up in the hands of detainees in a maximum-security prison? Also, and perhaps more significantly, how can the men be linked to ISIS? At the time of the escape, Edil Abdrakhmanov was serving life for membership in a terrorist group called Jaysh al-Mahdi (JM), which the State Commission for Religious Affairs had classified as a Shia organization. Why would he have made the unlikely switch to Sunni-backed ISIS?

The six dead escapees were not the only casualties of the prison break. In the months leading up to the escape, the head warden of SIZO 50, Imankul Teltayev, had written several letters to the highest-ranking officials in the Kyrgyz State Prison Service (GSIN), pleading for the life-sentence prisoners to be moved to more appropriate facilities. His requests were ignored. In the letters, Teltayev explained that SIZO 50 was understaffed and surveillance cameras in the detention building weren’t working (the latter a fact mentioned in passing by the prosecution, too).

After the breakout, Teltayev penned his own reconstruction of events in which he pointed a finger at the State Prison Service. “If the GSIN leadership had organized a timely transfer of the life-sentence detainees to an adequate institution, [I] believe this crime would have not been committed,” he concluded. Teltayev was arrested for dereliction of duty following the prison escape. On November 20, 2015, he was found hanged in the prison medical ward in what the authorities dubbed a “suicide,” a fact contested by his relatives, who met with him the previous morning and found him to be in good spirits.

With most eyewitnesses to this case dead, and the survivors locked up, the Kyrgyz authorities took control of the narrative. They blamed the mayhem on terrorism and professional incompetence. But the contradictions and lack of supporting evidence for their version of events suggest that there is more to this than meets the eye. To begin examining these happenings one must look back to 2010, when a new elite cadre ascended to power on the heels of the bloody revolution that ousted Kyrgyzstan’s corrupt second president, Kurmanbek Bakiyev, ushering in a short-lived period of hope for a better future.

The terrorist group that wasn’t

On April 7, 2010, a rioting crowd stormed the presidential palace in the center of Bishkek, precipitating the ouster of President Bakiyev, who had served as the second president of Kyrgystan since the collapse of the Soviet Union brought about independence in 1991. The names of the protesters who died in the uprising are now emblazoned on the outer fence of the palace, known as the White House. On that fateful day, elite Alfa special force agents belonging to the State Committee for National Security (GKNB) were positioned on the roof of the White House and were charged with opening fire on protesters, contributing to the day’s final toll of dozens killed and hundreds injured.

Despite the efforts of the interim government, Kyrgyzstan was in turmoil for the remainder of 2010, even as it held a constitutional referendum on June 27 and parliamentary elections on October 10. Instability peaked in June, when Kyrgyz and Uzbek crowds clashed for four days in the streets in the southern provinces of Osh and Jalal-Abad, leaving behind a trail of death, displacement, and destruction.

Against this backdrop of instability, small-scale incidents such as robberies, attacks on policemen, and explosions continued in the country, including a blast on November 30 that rocked the Sports Palace in central Bishkek. At the time, the Sports Palace had been chosen as the venue for the trial of Bakiyev and his family (in absentia, as they had fled into exile), for their role in ordering the violence of the April revolution, as well as eight Alfa operatives who were accused of shooting and killing protesters on Bakiyev’s command.

After initially ascribing the Sports Palace explosion to separatists bent on destabilizing the country, the authorities reneged on that narrative and blamed elements linked to the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) and the Islamic Jihad Union (IJU)—two terrorist groups active in Afghanistan—for the attack. Little corroborating evidence was presented to support this allegation, which GKNB Chairman Keneshbek Dushebayev built upon during several media appearances in the following weeks, claiming that Kyrgyzstan and Central Asia were in the sight of international terrorists aiming to create havoc in the region and the world at large.

At one press conference the following January, Dushebayev shocked journalists with the revelation that a home-grown terrorist group with international connections called Jaysh al-Mahdi (JM), a peculiarly Shia-sounding name in Sunni Kyrgyzstan, had been all but disbanded. He went on to list a series of attacks JM was accused of carrying out, naming the explosion at the Sports Palace, and added that the group was planning to bomb the US Embassy in Bishkek as well as the Manas Transit Center, a key transportation hub out of Bishkek’s international airport for US and NATO forces operating in Afghanistan.

The timing of the announcements coincided with visits from high-level US officials, like then Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, who were in the region to reiterate the United States’ commitment to fighting terrorism and religious extremism in Central Asia and Kyrgyzstan’s important role in this battle. Geopolitical intelligence platform STRATFOR was one of the first to pick up on this extraordinary chain of coincidences, which effectively appeared to place the Kyrgyz authorities at the forefront of the fight against international terrorism side, by side with the US. STRATFOR reported that,

Under the current circumstances, it is much more likely that the Kyrgyz [interim] government and security forces are manipulating the terrorist threat in order to justify their own crackdowns and to get outside support from countries like the United States, as well as Russia.

On both counts, it worked. Despite failing to establish long-term stability, the interim government managed to cling to power and guarantee the successful transfer of assets—those owned by the former president, and his family and cronies included—into the hands of the new elites, who turned out to be as corrupt and rapacious as their predecessors. Hope for reform was the first victim of “terrorism,” whose threat the interim government exaggerated to draw attention away from its failures and focus it instead on, as STRATFOR put it, “exerting control over the restless country.”

The new authorities received the US’s stamp of approval, too, which significantly increased funding for counter-terrorism and counter-narcotics training, including for the GKNB Alfa special forces. Demoralized after the revolution, facing public trial and shame for the wanton killing of protesters, the GKNB and its Alfa units had successfully been rebranded as the population’s main line of defense against the scourge of domestic terrorism and as a US ally in the global war on terror.

From decorated revolutionary to JM terrorist: Edil Abdrakhmanov’s story

At about 16:00 on January 5, 2011, Alfa special forces conducted a raid on a nondescript house in Besh Kungei, a village less than twenty kilometers south of the capital Bishkek, with the aim of apprehending three alleged members of a terrorist organization. Or at least this is the official story. According to a former GKNB official with almost two decades in the service who spoke on the condition of anonymity, no negotiations with the suspects were conducted to secure their surrender. Instead, security services showered the house with bullets; a ballistics report later found more than one thousand shell casings in and around the property.

This approach strongly suggests a shoot-to-kill policy that has become standard operating procedure for the Kyrgyz security services when dealing with terrorism suspects. Miraculously, one of the wanted men survived the onslaught and was taken into custody. Less than two weeks later, GKNB Chairman Dushebayev gave his famous press conference revealing JM’s plots to the nation and the world. On the same day, the GKNB detailed in a press release the results of their ongoing investigation, implicating sixteen people in the organization’s activities, all Kyrgyz citizens but one, a Russian passport holder. The latter was Edil Abdrakhmanov, the only survivor of the Besh Kungei operation.

The press release added that,

Starting in 2007, [these people] have hatched their criminal ideas and plans, and in 2010 in the house of one of the active members they created and joined a terrorist organization called Jamaat Kyrgyzstan Jaysh al-Mahdi, which translated from Arabic means ‘army of the righteous ruler.’

There is only one problem with this account. Abdrakhmanov wasn’t in the country when the authorities imply he was. In 2000, his mother had taken then fourteen-year-old Edil to Russia, where he had steadily lived for the better part of a decade until his return to Kyrgyzstan just before the April 2010 revolution, as she very keenly recalls. In Russia, he met his wife Nadira, a Kyrgyz migrant worker, whom he married in 2008 and with whom he has a son and a daughter. The GKNB presser appears glaringly unaware of Abdrakhmanov’s almost decade-long absence from the country and fails to explain where the alleged JM members met, how and where they concocted their plans, as well as other key aspects of such a sensitive and highly publicized case.

For its part, the mostly pliant national media continued presenting the official version of events like a mantra, even after it surfaced that on April 7, 2010, Abdrakhmanov had participated in the storming of the White House in Bishkek and, in the ensuing mayhem, had helped remove the bodies of the dead and take the wounded out of the line of sniper fire. Such was the trust he gained with the interim government that he was appointed a member of a special mission to deliver humanitarian help to Osh, in the aftermath of the violence that ravaged the country’s south in summer 2010. Abdrakhmanov was given an award by the interim government for his contribution to the humanitarian effort. To this date, authorities never clarified how a revolutionary and government-anointed activist with no previous criminal record could morph into a dangerous terrorist in just a few months.

Part of the problem was that Abdrakhmanov was viciously tortured into confessing. Torture is widespread in Kyrgyzstan, and the use of confessions extracted under torture as proof in a court of law is common. The JM case is emblematic of the country’s systemic failure to uphold a defendant’s fundamental right of presumption of innocence. The majority of the people implicated in the case reported having been tortured and often described a similar pattern of abuse.

While the authorities claim that Abdrakhmanov lost his right eye during the Besh Kungei raid due to a shard from an explosion, Toktoim Umetalieva, a civil society activist who has closely followed the JM case from the beginning, maintains that this was as a result of severe beatings at the hands of interrogators. Speaking to the human rights organization Memorial, Abdrakhmanov’s mother said the GKNB investigators had “put a bag on [his] head, stunned him with electroshock, kicked him. [Edil] fainted during interrogation, he wasn’t fed for three days, his blanket was taken away.” The torture was so unbearable that he once tried to kill himself by slitting his wrists with a razor blade “so they’d stop beating him,” she added.

Often, interrogations took place without a lawyer present. According to the Memorial report circulated to relevant parties,

At a hearing on February 27, 2013 [suspects] Edil Abdrakhmanov and Aibek Korgonbekov addressed two GKNB operatives who were giving evidence in court, saying that it was they who had beaten and interrogated them without a lawyer. [The] operatives answered that they ‘conducted interviews’ and could do that without a lawyer, allegedly because they were part of the investigative team.

Still, the following July presiding Judge Ernis Chotkorayev sentenced Abdrakhmanov and others to life in prison for terrorism in connection with the JM case. According to one lawyer for the defense, Judge Chotkorayev had come under enormous pressure from the Council on the Selection of Judges to deliver guilty verdicts or else face retribution, such as possibly losing his job. Executive interference in the judiciary is common in the country and this has undermined the public’s faith in the institution, which in a 2012 poll was found to be the “most loathed” in Kyrgyzstan.

With all the defendants sentenced, the JM case appeared to be closed. In June 2015, the appellate court upheld most of the sentences, including Abrakhmanov’s, who in the meantime had been transferred to SIZO 50. It was there that Abrakhmanov met Itibayev for the first time. Itibayev had been remanded in custody in SIZO 50 on September 5, 2015, on charges of belonging to an alleged ISIS cell.

Different times, same strategy: enter ISIS

On July 16, 2015—a few months before the prison break—explosions and heavy gunfire ripped through the humdrum of another scorching summer day in Bishkek. Soon the news was out that GKNB Alfa special forces and police were engaged in a firefight with an international terrorist cell in the city’s southern district. The hours-long special operation caused an extensive fire that continued into the night, burning several buildings to the ground, the alleged terrorists’ hideout among them.

Within twenty-four hours, GKNB spokesperson Rakhat Sulaimanov disclosed to the public that the previous day the GKNB had killed six members of the first ISIS cell in Central Asia, and arrested seven others. “Investigations revealed that the group had received finances from Syria to buy chemical components for explosives,” Sulaimanov added, indicating that the group was planning to attack mass prayers in Bishkek’s Ala-Too central square to mark the end of Ramadan on July 17, as well as the Russian Kant airbase about twenty kilometers east of the capital.

The evidence behind these revelations, however, was once again extremely thin. Soon it came to light that at least four of the six killed in the operation were well-known criminals, including a prison fugitive on the run since April. Among them was also Tariel Dzhumagulov, also known as Tokha, a prominent member of the post-Soviet criminal underworld with a record of disorderly conduct, robbery, possession of firearms, and extortion.

Tokha was linked to Kamchybek Kolbayev, the Central Asia point man of the Brothers’ Circle crime syndicate. Even the relatives of the four dead confirmed that their sons were criminal authorities but not terrorists during a press conference in September; all were exasperated by the fact that the authorities refused to return the bodies of the dead, as Kyrgyz law stipulates in terrorism cases.

The video the GKNB prepared with the highlights of the special operation and the findings from inside the alleged ISIS safehouse, comprising weapons, ammunitions, and an ISIS flag, did not fully match the story the authorities were telling. Some pointed out that the materials and weapons on display were grossly inadequate to carry out an attack on a fully operational Russian air base such as Kant. Others questioned how the authorities could have recovered anything intact in the aftermath of the raging fire that ravaged the buildings in the area, let alone a pristine flag. An international journalist who visited the scene on the day of the operation dismissed such claims as “beyond ridiculous” and “a flagrant falsehood.”

The domestic and international environment had changed dramatically since the JM story had burst onto the scene in Kyrgyzstan. As of summer 2014, ISIS had emerged as the primary focus of international efforts against terrorism in the latest iteration of the global war on terror, despite President Obama’s announcement of its end only a year before. In parallel to the mounting offensive in Iraq and Syria, the US administration was eyeing a substantial troop drawdown in Afghanistan by the end of 2016.

As a result, Kyrgyzstan’s Manas Transit Center, the main travel hub for US and NATO forces flying in and out of Afghanistan, was shut down in July 2014, stripping the country of an important counterbalance to Russian influence. The Kremlin’s footprint in Kyrgyzstan had been steadily growing for some time, via a combination of infrastructural investments, military aid, and an expanding military presence with the signing of a fifteen-year extension on the lease of the Kant airbase in 2012. In August 2015 the country was pulled even closer into Moscow’s orbit when it joined the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), a Russia-led economic bloc.

Russia’s adventurism in Ukraine and its attendant economic difficulties had translated into serious doubts among a significant part of the population in Kyrgyzstan about the actual benefits of EEU membership. However, very little debate preceded the decision to join the EEU, which the Kyrgyz leadership eagerly supported. The media flurry around the special operation against the purported ISIS cell, in the weeks prior to Kyrgyzstan’s EEU entry being finalized, diverted the public’s attention from the EEU controversy and focused it instead on the threat of terrorism. The outcome was ideal for elites in Bishkek and Moscow.

Russian-language media, such as the Kremlin’s media branch Sputnik.kg, whipped up the fear frenzy with a barrage of articles on the anti-ISIS special operation and the specter of terrorism, which were paralleled by reports describing Russia as a bulwark against extremism providing military training and hardware to its Central Asian allies. With Putin’s decision to intervene overtly and directly in the Syrian civil war on the side of the Assad government, ostensibly to fight terrorism and extremism, elites in both countries could cloak themselves in the rhetorical mantle of the global war on terror.

By year’s end, attitudes toward Eurasian integration among the population in Kyrgyzstan had turned around, with 86 percent of respondents in a Eurasian Development Bank’s annual survey viewing it favorably, the highest such percentage in the EEU. Domestically, the ruling elites further strengthened their grip on power. Faced with parliamentary elections at the beginning of October 2015, President Almazbek Atambayev’s own Social Democratic Party (SDPK) ran on a ticket of stability and Atambayev stepped up his rhetoric against terrorism in the run-up to the polls. The SDPK won almost a third of the votes, becoming the biggest of the pro-Russian parties dominating the parliament. Moscow was entrenching its presence in Central Asia, while elites in Bishkek could benefit from Russia’s political, economic, and military patronage.

After the spectacular prison breakout later that month, the media machine went into overdrive. But as the manhunt climaxed with Abdrakhmanov’s recapture and the fatal shooting of Itibayev on October 22, 2015, the authorities’ version of events turned increasingly far-fetched, raising serious doubts about their claims to be fighting terrorism. At the heart of those claims is the story of one man, who was killed after the prison break and purported to be a terrorist: Altynbek Itibayev.

ISIS, Jaysh al-Mahdi, or both? Altynbek Itibayev’s story

Altynbek Itibayev was imprisoned at SIZO 50 as one of the seven alleged ISIS terrorists captured in the July 2015 operation. He was also one of the escapees who was killed in the capture efforts that October. Due process had failed him time and time again in the Kyrgyz justice system.

Born in the southern city of Osh in 1977, Itibayev served in the Kyrgyz Army in the south at a time when the country was facing incursions by the Afghanistan-based Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan militants crossing the border from Tajikistan into Kyrgyzstan. Official Army papers show that between March 2000 and November 2001 Itibayev was posted to Karamyk border village, where Army headquarters were located and several battles against the IMU took place starting in 1999. Sporadic clashes continued until summer 2001 and finally subsided later that year.

“What upset him most was being accused of terrorism when he fought actual terrorists in the south,” Itibayev’s brother Meder maintained, referring to the ISIS-related terrorism charges for which his brother was awaiting trial. Soon after Itibayev’s escape from SIZO 50, leaflets distributed by law enforcement agencies around the capital described him as “a member of the banned group Jaysh al-Mahdi (JM).” Media outlets reporting on the breakout relayed information from the authorities in which Itibayev was said to have been previously sentenced for murder and the Sports Palace explosion on November 30, 2010, for which JM had been blamed and Abdrakhmanov and others had been sentenced.

The authorities’ reconstruction contains a fatal flaw, however. Itibayev had been arrested on April 22, 2009, and charged with the assassination of Sanzharbek Kadyraliev, then a member of the Kyrgyz parliament. This was at odds with several witness testimonies asserting that at the exact time of the murder he was at the Ministry of Transport and Communication. Despite this ironclad alibi, Itibayev was tortured into confessing by GKNB interrogators, who threatened to harm his wife and their three children (his wife confirmed that she received intimidating phone calls about their children, though she could not identify the callers). This was still President Bakiyev’s Kyrgyzstan, and Kadyraliev’s was one in a series of high profile killings many believe to be the work of the former president and his clique.

Itibayev was sentenced to life for Kadyraliev’s murder and, although it is unclear why and when exactly he was released, he stayed in prison from 2009 to at least October 2013. The authorities have yet to explain how he could have organized an attack at the Sports Palace while serving time. In prison, Itibayev shared a cell for some time with criminal authority Tokha. Itibayev’s brother Meder thinks it is plausible that Itibayev and Tokha might have been involved in some illegal business activity together, but he categorically denied the idea that his brother could have been a terrorist.

Following the prison breakout, the authorities’ narrative moves from the fanciful to the downright implausible. As they start associating Itibayev with JM—which the State Commission for Religious Affairs had classified as a Shia organization—they appear to forget that he was awaiting trial for allegedly belonging to an ISIS cell. In the span of three months, the Kyrgyz authorities had effectively accused Itibayev of being part of an extremist Sunni organization (ISIS) and an Iraq-born Shia group (JM).

Itibayev and Abdrakhmanov share a twisted trajectory here. Itibayev went from being accused of being part of ISIS to being part of JM, while his prison break co-conspirator, Abdrakhmanov, once accused of being part of JM, is now accused of being part of ISIS. The Kyrgyz authorities seem to have the two groups confused, or perhaps they’ve fused them together for expediency.

Abdrakhmanov was recaptured on October 22, 2015, and put on trial for, in the words of the prosecution, “plann[ing] to carry out terrorist attacks on the territory of the Kyrgyz Republic and, afterwards, to join the ranks of ISIS [Islamic State] in Syria and Iraq to fight against the secular authorities [there].” Following a short trial, Abdrakhmanov and the only two other survivors of the original nine escapees were sentenced to life on ISIS-related terrorism charges. His mother has met him on rare occasions since and said that Abdrakhmanov fears for his life.

Several requests to the GKNB press office asking for comment on the specific point of whether a terrorist suspect can simultaneously be a member of JM and ISIS went unanswered.

Whither the GWOT?

On the evening of October 22, 2015, in the words of Kyrgyzstan’s Interior Minister Melis Turganbayev, a special operation “to liquidate” the fugitive Itibayev was under way. The minister’s statement gave an official seal of approval to the previously unstated shoot-to-kill policy deployed in the past with terrorist suspects.

Turganbayev told the media that there can be no negotiations with terrorists, adding that it is international practice to kill terrorists on the spot. The minister was once again placing his country in the long tradition of the global war on terror, echoing the 2002 speech by former US President George W. Bush: “No nation can negotiate with terrorists, for there is no way to make peace with those whose only goal is death.”

Hopes that the Obama administration would fare better than its Republican predecessor were soon dashed. As author and journalist Jeremy Scahill put it in 2013, “effectively, Obama has declared the world a battlefield and reserves the right to drone bomb countries in pursuit of people against whom we have no direct evidence or who we’re not seeking any indictment against.” Under Obama, the global war on terror was expanded, indicating the extent of bipartisan consensus in US foreign policy circles on this issue. President Trump’s recent forays in Yemen strongly suggest continuity, rather than change.

When asked for comment on the role of ISIS in Kyrgyzstan, the US Embassy Public Affairs Officer in Bishkek, John Brown, responded via email that, “[f]or information on specific cases, I would refer you to the Kyrgyz law enforcement authorities.” He added that “[t]he United States has strong, active security partnerships with governments across Central Asia, and coordinates closely to counter the violent ideology of groups like [ISIS] and to fight terrorism in all its forms while protecting and promoting human rights.”

With Kyrgyzstan now more firmly under Russia’s security umbrella, concerns for human rights in alleged terrorism cases will hardly figure, even at the rhetorical level. For the foreseeable future, everything appears to suggest that the authorities will continue exploiting the terrorism threat to divert attention from their failures, eliminate dissent, and remain in power, no matter the cost in people’s blood and treasure.

After the special operation, images of Itibayev’s bullet-riddled body were publicized in the local media. Once the trial of the SIZO 50 escape survivals was over, his body was buried in an undisclosed location, according to Kyrgyz legislation in terrorism cases. “If they’d at least given us the body to bury him humanely,” his brother Meder sighed. “That way we’d now be at peace at last.”