When my editor asked me about cover ideas for my forthcoming memoir, Fairest, I told her that I was open to anything—except an image of my face. My book is in large part about my negotiations with appearance as a whitepassing trans woman, so I was aware that this caveat would be a design challenge. The request was instinctive. Trans women are regularly subjected to enormous scrutiny and objectification when it comes to our looks; people constantly speculate about and comment on not only our attractiveness but the nature of our transitions. I didn’t want to encourage potential readers to engage in this type of evaluation. But having acted on intuition, I found myself wondering how exactly trans women have been depicted on memoir covers over time. I began browsing online libraries, bookstores, and blogs to find trans memoirs published by American trade presses, some of which I’d already read. I ended up surveying nearly two dozen transfeminine memoirs written between 1964 and the present, an exercise that confirmed what I’d suspected: for decades, trans women’s bodies have been deployed as spectacle on the covers of these authors’ own books, which are meant to be vehicles for our thoughts and ideas.

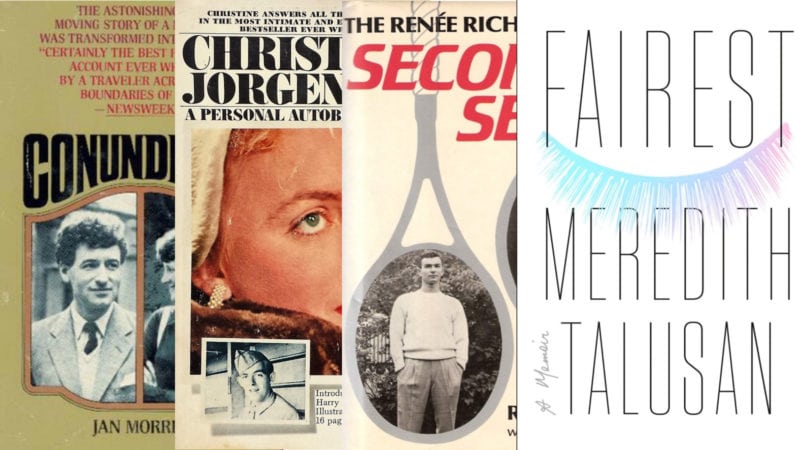

Christine Jorgensen’s large blue eyes and pouty red lips peek out from the cover of Christine Jorgensen: A Personal Autobiography, published in 1964. Jorgensen was the first American trans celebrity, and her popularity can be largely attributed to the public curiosity around her body, or, more specifically, the American public’s obsession over how someone who started life as a boy could possibly turn out so beautiful. A later edition of the book even contains an inset pre-transition photo. Similarly, the first edition of journalist Jan Morris’s Conundrum from 1974 features before-and-after images of the author on its back cover, and these were replicated on the front in a subsequent paperback edition. Professional tennis player Renée Richards’s memoir, Second Serve, displays before-and-after pictures from its first edition onward. It’s clear that publishers believed public interest over transition could fuel book sales.

Before-and-after photographs began to disappear by the late 1980s, but trans women’s memoirs have continued to feature their authors’ images on their covers—from Caroline Cossey’s My Story and Deirdre McCloskey’s Crossing in the 1990s to Janet Mock’s Redefining Realness and Caitlyn Jenner’s Secrets of My Life in the 2010s. The Renée Richards cover was even eerily echoed in Becoming Nicole, a journalist’s close account of the life of a transgender girl with an identical twin, published in 2015; on the front of the book, Nicole’s brother poses with her so that readers can imagine what she would have looked like had she continued to live as a boy without needing to feel quite so uncomfortable about it.

It’s true that authors, in general, sometimes appear on their own memoir covers. But publishers have tended to distinguish between celebrity memoirs and literary memoirs, the latter by authors who do not have public acclaim outside of their writing. Non-celebrity memoirs are far less likely to feature author images. When they do, which is rare, they will usually display photographs meant to evoke the mood of the author’s past (see Frank McCourt’s Angela’s Ashes or William Finnegan’s Barbarian Days, for instance) rather than to show us what the writer looks like. Transgender women memoirists muddy this distinction; often they become subjects of public interest through the public revelation of their trans status when they weren’t famous before (Jenner being a notable exception). This was the case for Jorgensen and Cossey in the early days and is still the case now, for writers like Mock and Jazz Jennings. In other words, no matter the type of memoir we have written and whether or not we are already known to readers, the fact of our existence as trans women has been enough to justify this use of our likeness.

There have been far fewer memoirs by transgender men. While the three I found from the early 2000s to Chaz Bono’s Transition (2011) exhibit author images on their covers, without relying on suggestive poses or pre-transition photographs, none of the six I examined that have come out since 2011 do. This compared to ten out of twelve transfeminine memoirs with authors’ faces on their covers published during that same time period. Thomas Page McBee’s memoirs Man Alive and Amateur, for instance, both feature flat, nearly abstract masculine figures. Cyrus Grace Dunham’s A Year Without a Name shows an image of two plastic dolls, and Daniel Mallory Ortberg’s forthcoming Something That May Shock and Discredit You a painting of a man seemingly deep in wracked thought, someone who is assessing rather than being assessed. Jackson Bird’s Sorted and P. Carl’s Becoming a Man don’t present a figurative image at all, just words on a jacket, and the same is true of two prominent books written by cisgender authors about transgender loved ones: Susan Faluddi’s In the Darkroom and Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts. Transmasculine authors typically have the freedom to frame their experiences apart from their figures, and cisgender women authors have managed through many decades of feminism to be afforded some of that same liberty. Meanwhile, the ideas of trans women are still inextricably tied to our images. It’s a challenge to relate our stories without pointing to our physical bodies as frames of reference.

The cumulative effect of all these memoir covers featuring trans women’s faces and bodies is to reinforce the idea that our transitions are an ongoing performance for a cisgender public. The message the publishing industry sends trans women writers is that this same public will be more likely to buy our books if we present ourselves as aesthetic objects for their enjoyment and satiation. And this message not only justifies but reinforces consumers’ inclination to objectify us and treat our bodies as entertainment. While the image of a trans woman on the cover of her memoir might have other functions—it could be read as a testament to her courage, for instance, or a statement of openness—I would maintain that in every case the intention of turning the author into an object for consumption is also present.

It can be argued that the publishing industry is merely following social trends, and that a publisher’s job is to figure out how best to get a reader to pick up and buy a book. If putting a trans woman’s image on the cover will accomplish sales goals, then that’s what the publisher should do. But (one hopes) there are other goals to consider beyond sales. One of them, I would contend, is to enlighten the reader and even to shift their perspective on a subject—in this case to allow the public to better understand the complex nature of transgender women’s lives. To accomplish this, it’s vital to alter the reader’s expectation, which more often than not will be that the most interesting aspect of trans womanhood is the woman’s appearance and how that appearance changed during transition.

I have a tricky relationship with physical beauty, one that I contend with and unpack during the course of my memoir, so it would have made a lot of sense to feature my own face on Fairest’s cover, and I confess to having been ambivalent about not wanting it there. It was, after all, the realization that I was seen as beautiful when I presented myself as a woman that catalyzed and propelled my transition, and I have many images from that period of my life to choose from because I was a photographer at the time. I struggle with the knowledge that I may not have transitioned or even thought of myself as trans at all had I not been perceived this way. It’s a complicated fact that has taken decades to accept and many pages of a book to explore, especially since that beauty is rooted in an imperialist history I despise.

Apart from not wanting to participate in turning gender transition into something akin to a circus sideshow, I also did not want to profit off my physical appearance and the advantages it has afforded me. As an albino Filipino, I am typically perceived as white and cisgender, and I find myself unable to divorce the benefits of this (because I have clearly benefitted from this) from the age-old Eurocentric brainwashing that has led to whiteness being associated with beauty. It felt hugely incongruous to question and challenge these privileges in my memoir while simultaneously utilizing them for book sales.

What’s more, one of the greatest luxuries of being an author is that I can separate myself from my physical presence. Since transition, I have had to continually contend with my ideas being perceived as less valid than before because of my appearance and my gender; it’s the classic double bind of needing to be good-looking as a woman (especially if you’re a trans woman) to be seen while at the same time being dismissed as unintelligent and frivolous once considered beautiful. But when I write, readers encounter the products of my mind, rather than their own perceptions of my body. I don’t consider it a coincidence that there is more gender parity among book authors than professionals in other fields, because the presentation of our labor requires significantly less physical interaction. I didn’t want to compromise the primacy of my ideas by selling my physical image along with my book.

Sensitive to my request that I not appear on the cover of a memoir that nonetheless interrogates my physical appearance, Penguin Random House senior designer Nayon Cho got it right from the start. Her first mockup was only edited very minorly before it became the final cover: glossy and white with thin, modern letters, the only physical image an illustration of a set of colored eyelashes. The eyelash connotes a physical presence without in any way literally representing me, and the whiteness of my skin is merely hinted at through the negative space that surrounds the drawing. The eyelash also evokes the socially inscribed and illusory nature of gender I explore in the book, as that ungendered body part becomes gendered female just by being observed and rendered in a spectrum of colors. Finally, the closed eye that’s implied prioritizes introspection over public display, even as it asks the reader to imagine the eye that is beneath the lid, questioning the reader’s desire to objectify and consume an image of femininity.

As much as I try to resist the social forces that shape transgender memoir covers, I have no choice but to live in a world where these forces operate. Any exercise of my mind must incorporate the experience of being a trans woman who has been objectified, and whose transition has been taken as spectacle. My work aims to show that there are many more complex and illuminating layers of that experience, ones that the desires of our cisgender-driven society have made it so hard for trans women to expose. There is, of course, a perfect aphorism to describe this gap between uncomplicated perception and complicated reality: Don’t judge a book by its cover. And there will likely always be a gap between what a publisher wants readers to think a book is so that they’ll buy it and what it actually is. Regardless of how it will affect my book’s bottom line, I won’t engage in that kind of miscommunication. I’ve spent too long letting the seemingly simple beauty of my face substitute for the immense complexity of my personhood.