Patience, n. A minor form of despair, disguised as a virtue.

—Ambrose Bierce, Devil’s Dictionary

The first time I modeled nude, I was 19 or 20, home from college for the summer and looking for work that paid more than minimum wage. Before leaving for New York, I had earned $6 an hour working at the Newmarket Movie Stop and Tanning in New Hampshire. It was a peculiar combination, slinging VHS tapes and DVDs between wiping down the tanning beds and setting their timers. The shop was in the basement of a gas station and convenience store, just a five-minute walk from my mom’s house. During slow shifts I did my calculus homework, textbooks splayed across the counter; often, my mother would come by with warm leftovers and we would talk over the to-go containers, condensation beaded on the lids.

I had held other odd jobs when I was growing up—hostessing and waitressing at a Japanese restaurant, organizing receipts for my mom’s friends who had their own businesses. But now that I was back home for the summer, I wanted more. More money, fewer hours, something at least marginally related to what I was studying: art. In high school, to build up my portfolio for college applications, I had attended a few figure-drawing classes at a community arts center in Exeter, a quaint mill town known for its elite private school. One model in particular was indelible in my mind: an older man with a hulk of a belly, a scrotum that hung to his knees, and a Gandalf-length beard, who brought props and pretended to be spearing fish in a stream for three hours. I thought of him when, after my first year of college, I called the arts center and left a message, asking if they needed models.

They called back a few days later and said they could pay me $20 an hour, which in 2009 sounded like good money to do close to nothing. The arts center sent over a simple form that included, along with blank lines for my name and address, one asking for my “body type.” I asked my mother what she thought. Though my stomach was relatively flat, we agreed that thin didn’t seem quite accurate. I had an overall softness, but plump seemed inaccurate and patronizing. My hips were padded, my breasts swollen by birth control pills, and my thighs strong from years of gymnastics, so we settled on athletic/curvy. Were they looking for something in particular? I wondered if there was wrong answer.

On my first day, I was careful not to wear underwear for an hour before arriving, so seams wouldn’t press lines into my skin. Behind a shoddy screen, I changed out of my clothes and into a terry cloth robe I’d borrowed from my mother. The students were mostly women who looked to be in their fifties. No one was there to lead the class; folks just signed in on a clipboard, dropped their money in an envelope, and circled their easels around a pedestal covered in shabby pillows. I waited in the oversized robe until everyone was ready, and then draped it over the back of a chair to begin. Thanks to my parents’ body positivity, I was never really plagued with self-consciousness. My mom was the one my friends turned to with questions about sex; who stuffed condoms in my suitcase when I headed to Italy the summer I was 16; who told me if I was ever at a party and felt unsafe to call and she would give me a ride home, no questions asked.

Over the phone, I’d learned that the class was structured around a standard set of timed poses. I began with incredibly slow movement, not stopping for five minutes: extending my left arm upward, sweeping it to the side in a port de bras, brushing my toes behind me into a pointe, old habits from ballet class lingering in my body. I graduated to one-minute poses where I tried to show off how limber I was, balancing on one leg and extending the other behind me, grasping my foot in my hands like a bow. Then five-minute poses, then ten. Finally, a couple of twenty- or thirty-minute ones, reclining and sitting, staying still even when my foot began to prickle and fall asleep. I posed in the dingy basement on wooden boxes that were padded with fleece blankets, surrounded by clamp lights casting dramatic shadows on my form. The students were there as hobbyists, but they complimented me on my ambitious poses and my stillness as I held them. They were startled to learn that it was my first time, and said they wanted me to come back; they were getting bored of the other options, the other bodies. I thanked them while attributing my skill to my past taking dance and gymnastics classes.

Studios are naturally messy places; the room is meant to contain the chaos of creation. They are places that accrue marks, paint splatters, dust—that house a jumble of materials. And though the room is a palimpsest, when a body is put to paper, its outline is fixed. Nevertheless, a model is always changing: her hair is getting longer, skin paler in the cloak of New England winters’ short days, fingernails recently clipped, muscles toned ever-so-slightly more by the exercise bike in the basement, a new mole shaded in by summer sun, a little more softness from all that sushi her boss lets her order at the end of shifts at her other job. The body grows and contracts continuously, accumulates, and sheds.

I have always been drawn to breasts, the beauty of their curves. In fourth grade, I dressed for picture day with a bathing suit top under my shiny marbled blue shirt, so I could appear to be wearing a bra. My chest was as smooth as a winter pond, and my belly puffed out the way children’s do before they grow into their frame. When I was in sixth grade and my breasts were just mosquito bites, I tried to convince my mother to let me get a bra. My mom called them buds and would comment on my friends’ new growth: Liz has buds now. Though I cringed at the word, all I wanted was for them to blossom on my own body. Finally, my mother deemed it appropriate (or got sick of my nagging) and bought me a training bra at Old Navy—a simple white cotton thing with two triangles and elastic straps, in a size S. I was pleased. Mostly I wanted kids at school to see the outline of the straps under my shirt.

As a young girl, I always had a hunch that I would get cancer. One night at my dad’s house, a year or so after I got my first bra, I touched my new breast tissue and thought for sure I felt a lump. My father was more composed than most in his role as single father to a daughter; he did not make a fuss or bring undue attention when he asked teenage me if I needed to get tampons at the grocery store. When I got my period, he bought me a poster of Orlando Bloom as Legolas, my first big celebrity crush, as a gift to mark the occasion. Still, that didn’t make it easy to ask my father to check the lump in front of the his-and-hers sinks of our upstairs bathroom. I have effaced the specifics of that moment. I don’t remember what season it was, or which direction I looked, or if his hands were hot or cold, if he wore his glasses or took them off. Of the moment we stood in front of that bathroom mirror and cinnamon-red countertop, all that remains is his assurance that I needn’t worry.

What I was feeling was the beginning of knowing that my breasts are fibrous, knotty, and roped with thick cords under my skin—which I now know means cancer is more likely and harder to find. My father’s mother, Jeanne, was thirty-four when she had a mastectomy and forty-four when a growth in her ovaries killed her. The loss of her shaped my father, who in turn shaped me, and tumors riddled the bodies of my father’s side of the family. Something about the mythos of Jeanne made me intuit that we had a shared destiny.

Two weeks into my job as a figure model, on my way to Exeter in the old Toyota Corolla I shared with my step-sister, I choreographed poses in my head to prepare. When I stepped onto the boxes, I entered a trance. The static of the radio, broadcasting exaggerated voices reading scripted ads, faded behind the curtain of my attention. I fell into the layers of my skin, my edges, my shadows. Each movement to select a pose and settle into it was a way of drawing a line. It was as if I was a ventriloquist of their pencils; when I flexed my toes, I pushed the graphite across the page for them to exaggerate the arch of my foot. I was both the hypnotist and the hypnotized. For me, finding stillness was not about concentration; it was like lying back in a pool and allowing myself to float, my body getting light, held by the air that inflated my lungs with each breath. My gaze into the shadowy back wall of the room pinned me in position. Stillness is often equated with being like a statue, or like stone, heavy. As a model, my goal was to become heavy and weightless at once, like a body sinking into the bottom of a trampoline bounce, about to be sprung upwards. I tried to simultaneously embody and alter the laws of gravity.

At the end of the last class I modeled for that summer, everyone wanted to show me their drawings. I had been curious, but too shy to do more than glance at the pads of paper during breaks. In some of the sketches I could not see myself—the body before me looked alien and unfamiliar—while in others the skill of the artist made my form more appealing. I loved seeing the shape of my body in so many hands, each one handling my form differently: a flourish of one person’s charcoal accentuating the shadow beneath my breast, my jawline and the soft wave of my stomach made more pronounced by another. The scales of graphite from H to B (for hard and black) altered the way my presence was felt: a greasy 6B pencil made my body seem fuller and confident, whereas a 4H could make me nearly lift off the page. In some way, each drawing felt like it was mine. I told them that I was trying to pose for the images that I would want to draw.

When I was 24, my hunch about cancer was confirmed. It happened quietly: I filled out a family history chart at the gynecologist’s office, and that was followed by a seemingly innocuous blood test—the ramifications of the potential results never thoroughly explained, and the mandate for counseling entirely neglected. It turned out that I was something called BRCA 1-positive. I have an 87-percent chance of developing breast cancer and a 50-percent chance of getting ovarian cancer. The best course of action: prophylactically removing my breasts and ovaries (resulting in immediate menopause) as soon as I was ready, ideally by age 35.

Suddenly, I wanted to escape my skin. There had been other times I wanted to flee my body, like the Sunday morning I was walking down Bogart Street in Bushwick, not half a block away from my house, and a boy who couldn’t have been more than 13 rode by on a bike and slapped me on the ass. It was a sunny afternoon and I was stunned, totally unprepared when he circled and came back for seconds. It wasn’t fight or flight but freeze that overtook my system, an instinct for stillness already present. Fight or flight allows you to move in space, toward or away from the danger, but I stayed fixed in my own body. Now, the force betraying me wasn’t an external one. It was my own body that would be most treacherous, that would force me to take action. The breasts I’d so longed for as a girl needed to be trimmed back, pruned like a tree to ward off excessive growth.

In sixth grade, there was a guy in my class who was nearing six feet tall. Everyone envied his height, while I was still hovering around four feet and was picked on constantly. When asked to line up in order of height for games in school, I was always first and this boy was last. We were comical next to each other, me at eye level with the waistband of his jeans. One day he didn’t come to school. Soon he had been absent a week and our teachers told us that he had collapsed: He was growing so fast that his heart (or was it his lungs?) couldn’t keep up. His height, admired by many, was killing him.

The line of my DNA that’s broken, that small typographical error, means my body can’t suppress tumor growth. I have always been short, short enough that people used my shoulder as an armrest, as a joke. I’d spent so much time feeling not tall enough, poked at for being a “little person.” Now there was potential for inappropriate, uncontrollable growth in my body, just like the boy in my class. How do you tell good and bad growth apart? Is it the rate of growth? Or the location? The time in your life when it happens?

I felt forced to betray my own body, to inflict horrific pain for the sake of protection. I was like a hermit crab being told to vacate my shell or face death; in the departure, parts of me would be torn off and left behind. But before that happened, I needed to sit still and wait for a while, opting for screenings every six months before turning my body into a site of excavation.

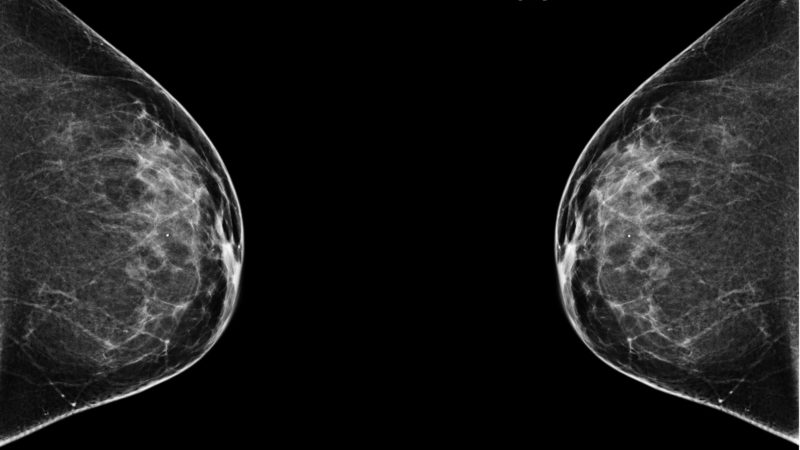

The first time I saw a mammogram of mine, I was stunned by the beauty of the image, just as I had been enthralled by sketches of my own body. A black background glowing with white tendrils of tissue. “So much of science is learning how to usher the light…inside of me,” writes Karina Vahitova. The X-rays of mammograms and radio waves of MRIs are not visible, and yet they penetrated my body and left mesmerizing traces of light everywhere. Each breast looked like a galaxy, time warped and glittering. Modeling had prepared me for the strange kind of stillness required by these imaging apparatuses: waiting fully exposed, holding a pose, and being patient despite the discomfort. And just as light helped artists see the contours of my body as I modeled, light traced my interior for doctors.

The jaundiced lights of the waiting room were different, though. Doctors were a combination of God and diviner, and in the waiting rooms I was forced to submit to their schedules, to be patient, to be a patient. Waiting is inextricable from expectation. To wait at the mercy of another person, place, or thing—it implies need. “I have no sense of proportions,” writes Roland Barthes when he describes the agony of waiting in A Lover’s Discourse. Indeed, I never had any sense of how long I sat waiting for doctors—three minutes would stretch to 45 without my full awareness—nor could I measure how much time had slipped away when I held a pose, my attention pricked by the timer going off. But even when my foot prickled and fell asleep, or my neck ached after looking to the left for too long, I wasn’t waiting for anything when I modeled, so stillness came more easily. At a doctor’s office, I could sit in the waiting room for hours before a nurse eventually led me back to an exam room, and then I’d have to wait more for the doctor. After I left, there was more waiting: anticipating the phone call with results, the next appointment in a few weeks or months. Ultimately, I was waiting to see which would come first: feeling ready to have surgery, or the arrival of cancer.

In New York the fall after my first modeling gig, I went around to art schools, hunting for more chances to play muse. The New York Studio School was promising, but they paid only $13 an hour, $14 for standing poses, and models were expected to pose for four hours at a time, twice a day, and often three days a week in order for painters to really develop a piece. Most of the good universities that paid better rates already had a backlog of interested and experienced applicants, and for me to model at my own university would have been a conflict of interest.

That year, I became my own model. In a photography class, my professor assigned us to take nude self-portraits. Is this appropriate? my classmates and I whispered to each other. I liked how uncomfortable it made me. Though I had modeled for others, it was different to fix my image in a photograph and know that the first audience would be my peers. I asked a friend to help me take the pictures. I bought a bunch of paint, put some plastic down on the floor of my dorm’s common room, and slowly smeared lines of color over my skin while she clicked the shutter. Later, editing the images on the computer, I amplified the colors on my skin to make my body an abstraction. My breast folded into a smear of vermillion. What appeared to be a crease of skin was actually two colors mashed together.

In Ways of Seeing, John Berger writes, “To be naked is to be oneself. To be nude is to be seen naked by others and yet not recognised for oneself.” The point of this abstraction was not to erase my body, nor was it meant to cloak my nakedness in any sense of privacy—I wanted to show up fully as myself. In hindsight, the pictures are crudely bright and far from subtle. I wasn’t aware then of how rudimentary they were, compared to body-centric works by artists like Carolee Schneeman, Hannah Wilke, Janine Antoni, and Ana Mendieta. Ten years later, I’m not exactly proud of images, but I felt proud in the process of making them. And I can see that I was mining something. Stripping in front of drawing classes made it easier to remove my clothes for doctors over and over again, and later, I would be glad there were images of my body that weren’t medical scans.

Those images took on a life of their own. They were part of three gallery shows, two in New York and one in China. They evolved into other bodies of work, where I covered myself in wet book pages and took baths with cow bones. When I brought in those pictures for critique, my teachers could not look at me the way the people in the figure drawing class could—that is, with critical distance. They recognized me, à la Berger’s definition of nakedness. They said my beauty distracted them. When I modeled for figure drawing classes, the people who drew me were, physically, far closer to my unclothed body, but they were able to keep an objective distance. Now it was my own presence in my photographs that was a problem, as if the boldness it took to make them—and to be myself, naked—weakened them. Suddenly, being nude and anonymous seemed desirable.

Recalling those pictures now, the young woman in them is familiar but distant. How can a body of work stand apart from my actual body?

For the screenings I undergo every six months, I alternate between cancer pavilions (for mammography and MRIs to scan for lumps in my breasts) and birth centers (for ultrasounds to detect abnormalities in my ovaries). In the oncology wings, I sit on leather chairs that are too smooth, suggesting no sign of human contact. I’ve never experienced such profound loneliness as I do in these places. My youth sets me apart, and of course, the fact that I am not sick. I sit and wait among foreshadows.

Ultrasounds are often a more optimistic sort of medical imaging. Most of the women in the waiting room are about to explode with babies; they are careening into motherhood, plump and fertile, growth of the good kind spilling over in every direction. Many of them have kids in tow, crying and nursing and grabbing for iPhones to pass the time. I stand out less in these rooms—the other patients can imagine I just haven’t started to show.

It’s impossible to get comfortable in these chairs, too, though it’s not the chairs themselves, but the reality of sitting there, what I’m waiting to do. Ovarian cancer has symptoms so generic and common—bloating, loss of appetite or feeling full suddenly, pelvic or back pain, fatigue, and constipation—that when it’s found, it’s very often too late: Stage 4. The first gynecological oncologist I met with told me in a gravedigger’s voice that after fifteen years of practicing, only one of her patients with ovarian cancer was still alive five years after diagnosis. Her brutality, I understood, was a version of protection. At 24, when I told her I didn’t want kids, she told me to have my ovaries removed within the next year if I was ready, knowing full well it would send me into early menopause—and that I would be at greater risk for heart disease and osteoporosis, and, because I’d likely be put on hormones, breast cancer. That’s how bad the odds are for living through ovarian cancer; those were risks she was well willing to take.

They couple the vaginal ultrasounds with a CA-125 blood test, looking for a spike in a certain protein. Everything comes back with a caveat: “This screening does not confirm or deny the presence of cancer.” Most of my doctors recommend prophylactic surgeries ten years before the earliest incidence of cancer in the family, so I was gambling as soon as I got the genetic results. They never talk about the sexual consequences of these surgeries: the loss of sensation in the breasts, the potential decline in libido and vaginal lubrication. Nor do they discuss how to deal with the way my body would be new to me, how to handle feeling self-conscious when I am intimate with someone else. They’re presumptuous, encouraging me to have children before I submit to surgery. The gynecological oncologist at Mass General is the only doctor in more than seven years of dealing with being BRCA 1-positive who has ever heard me out and believed me when I said I don’t want children. Men and women both have dismissed me, time and time again, said I’ll change my mind, as if they are older and know better, as if it is worth risking my life to bear more life.

I have never wanted children. In my early 20s I used to stand in front of a mirror and distend my belly, to try on what it might feel and look like to have another life inside of me. On the wall in my old studio in Gowanus, I tacked a self-portrait by Diane Arbus, where she stands before a mirror wearing only underwear next to a medium format camera on a tripod, her stomach a half moon glowing in gestation. I made my own series of images imitating Arbus, photographing myself in the act of imagining, the act of playing dress up with an identity that I felt ambivalent about, couldn’t truly see for myself. The series was called Unlived Futures, all the lives I might have had with different partners, in different places, with different days, different appearances. I look at those images now and think they are beautiful, that the young woman in them looks natural and at ease—but the ease is because the act of wondering made me even more certain. The ease was not because it felt right to cup my hand beneath my distended belly; it was because I knew it was wrong. I wasn’t supposed to grow a baby inside of me. My body has enough growth to wrestle with.

In my final year of college, I started attending a Drink and Draw class at an art studio in Bushwick. I found myself craving the meditative trance I remembered from my time modeling: the hush of pencils rushing across paper as eyes flicked back and forth between body and page. I found the same calm when I was on the other side of the equation, sitting and drawing in the rows of folding chairs and gazing up at the clamp-light shadows on the model’s body. Breasts were always my favorite part of the body to draw. Each time I began a sketch of a woman, I started with the nipple, as if it were the center of the galaxy of the body.

But there wasn’t the same stillness in this class. They had coolers of Pabst Blue Ribbon and the room would be packed to the brim, standing-room-only every week. The guy who ran it would stand in the back, DJing loud music. I would fidget in my seat and fold my too-short legs up under me since they didn’t touch the ground. Or I would shift my weight around. Move my large 20×24 brown paper pad. Change pen colors. Some weeks the model was fantastic and I got lost in my work. Other weeks—usually when it was a male model—I’d find I couldn’t get a handle on their body. I would grasp at their form, searching for something to hold with the line of my pen, but it just didn’t stick.

One weekend, I happened to meet the guy who ran the class at a dinner party. I told him if he ever needed a model I’d love to jump into the lineup. A few months later, there I was, back on the pedestal, making 30 bucks an hour. But there was something different this time, and it wasn’t the better money. I was older, and the crowd was younger, but that wasn’t it either. When I posed, I found myself slipping into a different kind of headspace, one that wasn’t about falling into Rebecca Solnit’s “faraway nearby,” as I used to do. It was more like a hyper-presence. My gaze was not inward but outward. After posing for my own work, having the crowd around me heightened the intensity and intimacy. Standing apart on the pedestal, I felt emboldened. Sometimes I would choose to look one person in the class directly in the eyes, holding my gaze on them for several minutes at a time. To that one person, I presented myself as more than a well-lit form to be outlined and shaded in. I was someone they might recognize.

At the end of the class, or during breaks, there was an unspoken etiquette. The barrier of my robe had been resurrected. I’m not sure any of the regulars ever picked up on the fact that sometimes I sat in the chairs drawing alongside them. I would wait in line for the bathroom with the rest of them, and they would compliment me on my poses but say little more than pleasantries. They knew never to ask anything too personal, and certainly, never to ask me out. Objectification is a word that has soured, but in this instance, all I wanted was to be an object, albeit a powerful one. It was a power built out of refusal. If the artists who attended the class saw me as more than this job, if they wanted to know more about my life when I stepped off the pedestal, it would have been an intrusion—dismantling the power I gained from what I withheld.

It was dangerous to make me more human. The eros was in my own awareness that I could hold the attention of fifty strangers, that I chose to disrobe, that—unlike at the doctor’s office—I had allowed strangers to look at me. Reclining there in front of them, I felt a certain kind of rapture in being given an audience, in feeling in control.

When I used to ride the F train to work in Manhattan, I would often land in a seat across from a series of advertisements for plastic surgery. In one, a woman held two clementines over her chest, while in another, a woman held grapefruits. Across the bottom was an 800 number, peddling enhancement for cheap. Another ad for the same company cut straight to the chase, with an image closely cropped on a woman’s abundant cleavage, stamped “MADE IN NEW YORK.” I had always judged women who augmented their bodies with plastic surgery, believing that natural was always better. Several years ago, on a beach in Barcelona, I noticed a topless woman whose breasts ballooned upwards, implausibly resistant to gravity. I began a predictable rant to my partner at the time about the patriarchal pressures that are heaped on women—and then I stopped. Her breasts with their implants might have looked cartoonish, but mine might eventually, too.

My mother’s mother, Helen, found a lump in her breast when she was in her 70s, when I was in my freshman year of college. The cancer was at the early stage, but as soon as her doctor told her the results of the biopsy, she knew what she wanted to do. She didn’t need to hear about the many options. She couldn’t tolerate all the waiting, or maybe it simply felt unnecessary. She wanted her breast off, as if it was an alien limb, and didn’t bother with reconstruction. She took care of it so swiftly that I hardly had a chance to register that she had cancer, and sometimes, I’m ashamed to admit, I forget that she did. For the first few years after her surgery, she put a fake boob in her bra each morning, but over time the habit wore off and she stopped caring about it. She would go out to lunch with her girlfriends and leave one side of her shirt baggy.

Eventually, my choice will be between having a flat chest or breast reconstruction. Some days it’s easy to forget that I am healthy, that these surgeries are preventative measures. They call me a previvor.

Last October, I attended a conference on hereditary cancer, hosted by an organization called FORCE, which stands for Facing Our Risk of Cancer Empowered. Knowing I was a writer with a personal and professional interest in the topic, they gave me a scholarship to attend. I went, hoping it would help me feel more ready to have a mastectomy. The timing finally felt something close to right: I had good insurance because I was in graduate school; I had summers off, which seemed like a good time to recover; and I had a partner who supported me. I wanted to like the conference, to feel connected to women who shared my experience of having prophesies made about our bodies. But the beige ballrooms deflated me. The sessions were so technical they overwhelmed me: Postmastectomy Recovery, Menopause with Hormone Therapy, Menopause without Hormones, Hereditary Male Breast Cancer. I saw so many women there with other family members supporting them; I hadn’t even thought to invite someone along to make this less scary. Most of them had husbands, children, stable jobs with good health insurance; I was an artist and writer, relatively young and unsettled. I was lonely.

In the evening, the conference presented something it called “Show and Tell.” In anticipation, a long line of women wound down the wide, carpeted halls of the conference center. The few men who attended the conference weren’t allowed inside. When the doors opened, women rushed into a large space. Inside were four areas where different plastic surgeons and breast centers had set up tables, staffed with consultants offering information about their procedures and approaches. They had laid out an array of implants: saline, silicone, round, smooth, textured, tear drop, responsive, and cohesives (also known as gummy bear implants). And at each table, they were serving cosmopolitans and champagne. Waiters in black passed around finger foods, which seemed like a bad idea: Grab a bacon wrapped scallop, then fondle a fake boob! Prod the puff pastry, then smear the grease on the titty table!

It was all one big sales pitch, a competition: whose sleek booth could make you feel the sexiest, and convince you that you were getting an upgrade? There were carefully curated post-op photos glowing on tablets, displays with lush leafy backdrops, glowing pink lights, and glossy black table coverings. Everyone seemed to be networking, and the cacophony of the room made me frantic. One woman promoting a line of post-mastectomy clothing started chatting me up; when she found out I was a writer, she tried to convince me to write for the blog on her website. I had come here looking for camaraderie, for women I could fall apart with, who could understand what it was to mourn the loss of part of my body. Instead I had a handful of pamphlets from plastic surgeons and that woman’s card.

I ditched the hors d’oeuvres and was about to leave when, off to the side, I noticed a room cut off by a dark curtain. A large sign propped up on an easel reminded people that there were no men allowed. Pushing through the vestibule behind the curtain, I saw a table with a bunch of tube tops scattered on it, for the taking. What a strange giveaway, I thought. But when I lifted my gaze, there were no doctors, no tables of pamphlets, no sales pitches, no greasy finger food. In the corners of the room were easels listing a wide range of mastectomy and reconstruction procedures: no reconstruction, mastectomy straight to implant, nipple-sparing, mastectomy to expander to implant, various kinds of flap reconstructions (a procedure where one’s own body fat is used to recreate breasts). In front of me stood a dozen women with their shirts off, tube tops pulled down around their waists, along with thirty or forty others mingling around them, fully clothed. The room was boiling with warm conversation, as if this were the most normal situation in the world.

There were women whose breasts were flowering with elaborate vines of tattoos masking scars, while others had embraced realism to get tattooed nipples, with shading that made them look three-dimensional. There were women whose scars ran horizontally out from where the nipple had been, while others ran vertically or were hidden underneath the fold of the breast. There were women with reconstruction jobs that looked like the subway ads I’d seen, and others who had one implant that roamed off to the side of their chests. In a corner, the director of FORCE stood casually with her shirt off. A mother, who was fully clothed, brought a glass of champagne over to her daughter, who was topless and chatting to a group of curious women. I overheard the mother say that her daughter had gotten the mutation from her father’s side of the family. What a beautiful form of mothering this was. The bodies around me were 25 and 47 and 62. They were divorced and single and married and mothers and daughters and sisters and grandmothers and non-binary and lesbian and midwestern and Latina and black and Jewish.

I thought about all the time I’d spent posing unselfconsciously in rooms full of people. I had wondered whether I’d still be able to do that after I had surgery, and whether I would want to. Would I even be able to take off my clothes in the locker room at the gym without feeling the need to hide my chest? I hated imagining the stares. Now, in this room, these women made a sham out of the proud self-assurance I’d brought to being drawn naked all those years. How little I had been baring.

I slid over to a woman who looked about my age and had dyed red hair cut in a bob, joining a cluster of others who were asking about her experience of surgery. She had a bit of an edgy look and mentioned she was from “a flyover state.”

“I mean, I’m not pleased with the rippling,” she said gesturing to her right breast, where the implant was slightly visible and, without the padding of breast tissue, the skin wasn’t taut. “I might get it touched up,” she added nonchalantly. “I hooked up with a guy recently, and it’s been three months since I had this done and I was just super-straight with him before he took my shirt off. He didn’t seem to mind.” She turned to me. “Do you want to feel?”

I was suddenly aware that my hand was cold from holding a glass of champagne. Though I knew intellectually that breasts lose almost all sensation after a mastectomy, I shifted the glass to my left hand and tried to warm my fingertips before pressing softly on the slope of her breast. It felt entirely natural, and in the dark, I wouldn’t have been able to tell the difference.

Posing for art classes had been a way for me to gather the gazes of others and funnel it into power for myself—but I was always untouchable. I stood apart from the people who looked at me. Surrounded by topless women in that room at the conference, it was the first time I felt myself settle into a sense of stillness about getting a mastectomy. There was some promise in the presence of this range of bodies: that I would get through it, that I would be okay. It didn’t erase how excruciating the loss would be, how taxing all the uncertainty was, but it anchored me.

A sketch is a draft, a warmup. All the incarnations of me that live in strangers’ sketchpads do not represent the person I am in this instant. They show a body that is tied to another day, another year, another emotional geography, another physical terrain. A woman who—depending on when the drawing was made—had longer hair, or was less determined, or more muscular, or had a slightly different constellation of moles and freckles. The drawings pile up and overlap. Often, they are unfinished. It’s in this way they most resemble my body.