In “Memory Fragments,” one of the essays in this issue, photojournalist Alina Tiphagne recounts her first assignment. When asked by a classmate she has a crush on to photograph a friend’s birthday party, she loads a roll of film into a plastic camera—and accidentally ruins it. In a panic, she does the only thing she can think of: she describes the lost photographs out loud in intricate, loving detail. The moment becomes a kind of origin story, not only for the photographer, but for the impulse to reimagine what we can’t recover. “These images are great,” the classmate responds sweetly after hearing their descriptions.

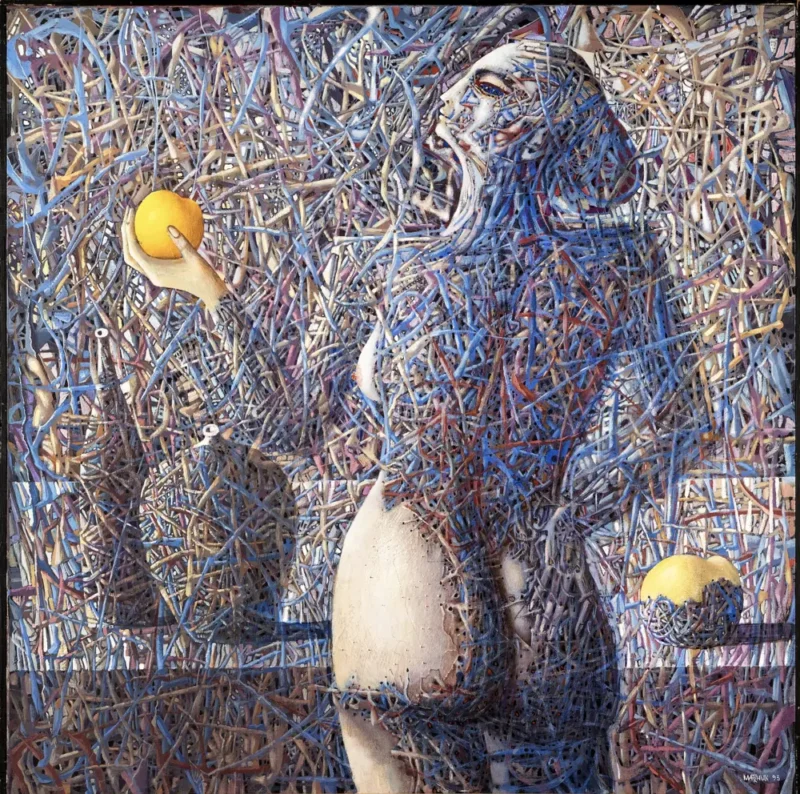

The April issue is similarly full of elusive images—captured precisely by the unflinching voices featured. These images appear in fragments, in flashbacks, in Kashmiri forests and Brooklyn hospitals, in lurid cityscapes and musty cupboards. Some live on a hard drive. Some live in the body. How do we grapple with the images we inherit, carry and invent? Across essays, fiction, poetry, and folktale, our April contributors ask this question. These aren’t just stories about looking; they’re also stories about being looked at, flattened, misread, or left out of the frame altogether.

Nina Martinez’s personal essay “The Grind” brings us into the heart of state violence in Duterte’s Philippines—through the inbox of a newsroom image editor. What begins as a job sorting images becomes something closer to entanglement, as dead bodies accumulate in folders, and the drug war quietly gets filed beside the red carpet stills. Meanwhile, Soraya Palmer’s personal essay “Strong as a Mule, Thick as a Rope” registers the way pain in Black women’s bodies is so often dismissed, even when the evidence is undeniable. Blending medical imagery with the register of body horror and a legacy ranging from gynecological experiments to forced sterilizations, she renders the Black woman’s body as an intimate site of struggle and survival. And finally, in “Memory Fragments”, a piece guest edited by Meena Kandasamy, Alina Tiphagne assembles a photo essay without photographs—layering a personal narrative from the South Indian town of Madurai, visual theory, and the history of queer archives to explore what it means to be legible in a world that refuses to see you.

In Yasmin Adele Majeed’s short story “Chicken,” a young woman arrives at her fiancé’s family reunion—once her mother-in-law’s academic protégée, now a member of her home—and feels the weight of the family’s gaze on her. It is a story of distance, perception, and quiet defiance, all rendered in crisp, coastal Cape Cod light. In parallel, Maria Kuznetsova’s short story “The Glow” follows a struggling Ukrainian-American writer in the aftermath of an ectopic pregnancy as she searches for her grandmother’s apartment in Santa Monica. Haunted by old snapshots and new billboards, she enters into a jagged chase for permanence in a world that keeps refreshing itself.

In our Global Spotlight, “Soda Byor, Boda Byor,” Onaiza Drabu tells a Kashmiri folktale in which a child and his caretaker can only find their way out of the forest by telling stories. One story isn’t enough. Nor are two. The spirits demand three: two of love, one of pain. By insisting that what is remembered and retold lives on, this tale turns stories into maps and oral tradition into a living archive—where storytelling is not just a path home, but also a reason to stay in the forest a little while longer.

Finally, we close with three poems by the Ghanaian-American writer Afua Ansong (“Black Girl in Wyoming,” “Lucky Anointing Oil,” and “David”) and three by the Brazil-born poet Esther Lin (“Midnight Service,” “Because I Was Protestant,” and “A Citadel in Queens”)—two writers intimately attuned, as undocumented immigrant women, to the experience of being read before you speak. Ansong’s work moves between Ghana and the U.S., between survival and suspicion, tracking the absurdities and stakes of belonging. Lin writes from the heart of girlhood and evangelical Queens, where the divine and the carnal live in tension. Both poets ask what it means to survive a world that projects its own story onto your body, as well as what it takes to write, or speak, a different ending.

Ultimately, across visual, narrative, and lyrical registers—and drawing from Filipino, Kashmiri, Ghanaian, Ukrainian-American, South Indian, and Afro-Caribbean American experiences—these works refuse to treat “the image” as neutral ground. They reveal how images can oppress or liberate, distort or illuminate, confuse or clarify. And like that first roll of film in “Memory Fragments,” they remind us that even when the picture doesn’t develop, you can still name what was there.

–Youmna M. Chamieh, Editor-in-chief

—

“Chicken”–

A gracefully executed story with echoes of Elena Ferrante’s The Lost Daughter, “Chicken” centers upon Risham, a young girl who attends the family reunion of her fiancé in Cape Cod – and walks into an unwelcoming situation riddled with underlying tension and unspoken resentment.

—

“The Glow” –

A heartfelt and character-driven story, full of humor and wit, “The Glow” follows Oksana, a young Ukrainian American woman, who tries to navigate a series of personal and professional disappointments, all while searching for her grandmother’s former apartment in Santa Monica—only to come face to face with feelings of inadequacy, the complexities of immigrant identity, and the difficulties that come with artistic ambition.

—

“Memory Fragments” –

As argued in this finely wrought essay, for queer lives, marginalized histories, and unseen experiences, even the ‘perfect’ images do not guarantee legibility. This essay asks: What does it mean to exist unseen? What truths can an image hold when visibility itself remains elusive?

—

“The Grind” –

In this powerful essay that explores the workings of authority and assent, Nina Martinez recounts her experiences as a journalist covering the extrajudicial killings that took place under Duterte’s government in the Philippines.

—

“Strong as a Mule, Thick as a Rope” –

In this unflinching essay, Soraya Palmer looks at the painful history of disparities faced by Black people in the medical field, and how racism can spawn body horror, manifesting itself as PTSD, depression, and fibroids.

—

“Soda Byor, Boda Byor” –

In this Global Spotlights story, Kashmiri folklore and oral tradition come alive as two forest spirits demand stories of love and pain in exchange for guiding a lost child and his caretaker home.

—

“Midnight Service,” “Because I was Protestant,” “A Citadel in Queens” –

Three poems by Esther Lin, a Brazil-born poet who grew up undocumented in the United States. Set in evangelical Queens, these poems grapple with religion, intimacy, and girlhood, revealing how the images projected onto us can scar or sanctify.

—

“Black Girl in Wyoming,” “Lucky Anointing Oil,” “David” –

Three poems by Afua Ansong, a Ghanaian-American writer and educator. From the high plains of Wyoming to the streets of Accra, from the biblical to the bureaucratic, these poems examine what it means to belong—to a country, a faith, a story—when the terms are always shifting.