Stephanie LaCava’s The Superrationals, set largely in 2015, is a “before the fall” novel. Like their Austro-Hungarian counterparts in Hermann Broch’s The Sleepwalkers or Robert Musil’s The Man without Qualities, the Americans in The Superrationals belong to a wealthy, cosmopolitan elite in a transnational order they do not know is on the verge of collapse. They work in the art world, in the publishing industry, in the academy, or for NGOs. They spend significant time on transatlantic flights and intercontinental flights and in cabs and on the Eurostar. They wear their diplomas like identification badges and, needless to say, the only public college mentioned in the novel is a certain graduate program at the University of Iowa. They talk about politics rarely, and when they do their positions are meant to be taken as expressions of sophisticated taste. “She went through her days trying to derail her life and privilege,” LaCava writes of one of them, “never quite succeeding.” Economically advantaged, they do not realize that they are politically precarious. They do not know that in the darker recesses of the internet, people whose paths they will never cross are beginning to label them “globalists” with a vengeful sneer.

When The Superrationals opens, Mathilde is an orphan in her late twenties, the same age her mother was when she died in a mysterious accident. Mathilde is said to look identical to her mother, the legendary New York editor Olympia de Saint-Evans. She worries that she is “late to her mother’s schedule” professionally and emotionally, and spends the rest of the novel struggling to become her mother as a means of keeping her symbolically alive. This doomed project includes following a career path that is both more practical and less lucrative than she’d like; acting as a surrogate parent to her troubled friend, Gretchen; and by marrying young, then carrying on an affair with one of her clients in a farcical imitation of her mother’s happy relationship with Robert, the famous novelist she once edited. If the novel’s narrative machinery is set in motion by what seems like a contrivance—Robert selects Gretchen’s on-again off-again boyfriend for a writers’ residency at his mansion outside of Paris—it is because elite circles are necessarily small, and all small societies are necessarily endogamous.

Mathilde works for an international art brokerage firm called the Contemporary, but in the first decade and a half of the 21st century, “the contemporary” has become a peculiar oxymoron: nostalgia that fancies itself cutting-edge. History’s not over, it’s everywhere. Mathilde’s nosy coworkers at the firm are a Greek chorus whose stage is a group chat window. The fashion sense of more than one female character is compared to the style of a French New Wave actress. Gretchen—who like Mathilde is a frequent subject of gossip—cannot speak of her love life without namedropping Kierkegaard, von Neumann, or Deleuze. The artists and novelists Mathilde writes about in her unfinished dissertation, passages from which are interspersed with the narrative, are drawn almost exclusively from the 60s and 70s. The document is aptly titled, Transmuting Desire: Memory, Mannequins, and The Contemporary Reliquary: An Exploration of the Unsaid, Unseen, Uncanny, Space, The In Between.

Reading The Superrationals, I was reminded of Mark Fisher’s observation about Alfonso Cuarón’s 2006 film Children of Men (in his book Capitalist Realism, which one can easily imagine on Gretchen’s shelf). In Children of Men, a mysterious virus has made childbirth a thing of the past. Fisher reads the film as an allegory of a sterile, historically hyper-conscious culture incapable of imagining, let alone generating anything new. Just as in Cuarón’s film, in LaCava’s novel there has been a disruption of the generational order, symbolized by Olympia’s premature death, but also attributable to the unwillingness of Robert’s generation to yield its accumulated powers. The Boomer and Gen-X characters of The Superrationals have put immense concentrations of financial, educational, geographical, and cultural capital at the disposal of the book’s Millennial characters, but the catch is that they must spend it all tending their ancestors’ graves.

When viewed from the vantage point of the present, however, their lives are enviable. A society in which people’s major concerns are the caddishness of their romantic partners, the pettiness of their co-workers, and the uninspired high art objects produced by the culture industry around them is a society in relative good health. Of course Mathilde and Gretchen are “out of touch” with the lives of the people who do not belong to their social milieu. This is the charge every social fragment is always leveling at every other social fragment, but it is only in a disintegrating society that being “out of touch” starts to take on political significance. In fact, if there is one failure to blame most of the characters of The Superrationals for, it is for failing not to become us, that is, the people who will be reading about them in 2020. How could they have done something so stupid?

The tragedy of every cautionary tale is that if you’re telling it, it means the caution was not heeded. Power, that is, politics, is never absent from any milieu, no matter how apparently insulated, at any time, no matter how apparently peaceful or prosperous. And it cannot be ignored for too long without devastating consequences for those who benefit from it but refuse to acknowledge, exercise, or share it. In The Superrationals, power reveals itself most spectacularly in the person of Charles, Mathilde’s boss, during a last-minute work trip that Mathilde makes to London, with a heartbroken, drug-addled Gretchen in tow. Little more than a whispered name until the novel’s final pages, Charles appears in the narrative to serve as a sort of gate through which the recent past opens onto the present, a gate that is marked Et in arcadia ego. Protagonist and reader alike experience the two scenes he features in with a numb fatalism born of grim overfamiliarity.

If Charles is the worm in the apple of a fundamentally illusory paradise, Mathilde is an ingénue in an era that thinks that it has seen enough to make ingenuousness unbelievable. She is perfectly aware of her function at Contemporary: “Buy and sell. Manufacture connection.” Like the titular figure from Tiqqun’s pamphlet Preliminary Materials for a Theory of the Young-Girl, a popular art world text during the years in which LaCava’s novel is set, she is “consumer society’s total product and model citizen,” every bit as much of a luxury art object as the canvases she pedals in the capitals of Europe. Her body is a site of circulation and exchange, a kind of “living currency” in a world in which all the account holders are powerful men. Mathilde’s revenge against Charles is to momentarily inconvenience the firm by sending a series of expensive artworks to the wrong addresses, a minor kink in the otherwise smooth flow of capital, an act of sabotage, not protest, for which she is summarily fired.

In a typical bildungsroman, a narrative climax marks a change in the protagonist’s self-knowledge and therefore in her life direction. Yet after the incident with Charles in London, Mathilde returns to France, to a seventeenth-century mansion where her dead mother’s writer-lover is hosting her surrogate child’s writer-lover. In her luggage, she is carrying lingerie she bought at a store once patronized by her mother. “In an age of hybridity,” Mathilde asks herself, “why is transmission always binary?” It is—or ought to be—a rhetorical question. In the course of history, periods of apparent progress last only as long as it takes for the system to update itself. The uncanny, as Mathilde surely knows, is the return of the repressed, or, to put it differently, the point at which what was always already there can no longer be ignored.

But knowingness, especially historical knowingness, is not knowledge; and knowledge that never leads to action is merely refined ideology. In game theory—the leading dogma of the slice of the elite to which Mathlide’s boss and clients, the real power holders, belong—a player is considered a “superrational” if she or he assumes that all other players are also perfectly rational and will therefore make the same decisions. As long as this remains true, the superrationals will always win the game. But the assumption is itself hardly rational. It is a blind spot large enough to house an entire life, indeed an entire generation. All it takes is one irrational player to bring the roof down on everyone’s head.

“No one thinks the crazy is going to happen,” Robert writes, presumably thinking of Olympia’s accident. “Or they do, and then because they thought it, they imagine they can think it away.” Few cultures are as unprepared to deal with the unprecedented—the rupture, the crazy—as those that are simultaneously committed to the view that incremental political progress is a fact of life and that there is nothing new under the sun.

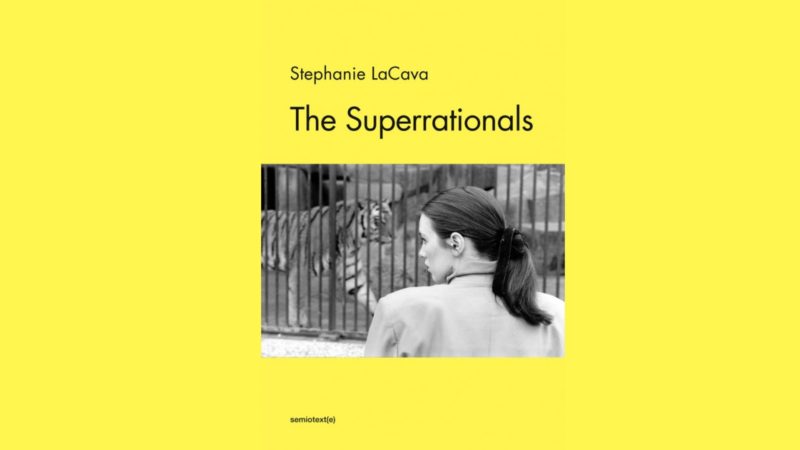

The last chapter of The Superrationals is ominously time-stamped “November 2015.” In a matter of days, ISIS militants will kill 130 people in Paris and a joke candidate for the Republican nomination for President of the United States will see his poll numbers spike as he capitalizes on primary voters’ fear of terrorism and resentment toward the global elite. On the novel’s cover is a black-and-white photograph by Hervé Guibert of an elegant young woman, her brunette ponytail tied discreetly with a thick ribbon. She is at the zoo. The camera is positioned as though it is about to tap her on the shoulder and say, “Don’t I know you from somewhere?” The tiger prowling the background is about to slip its cage.