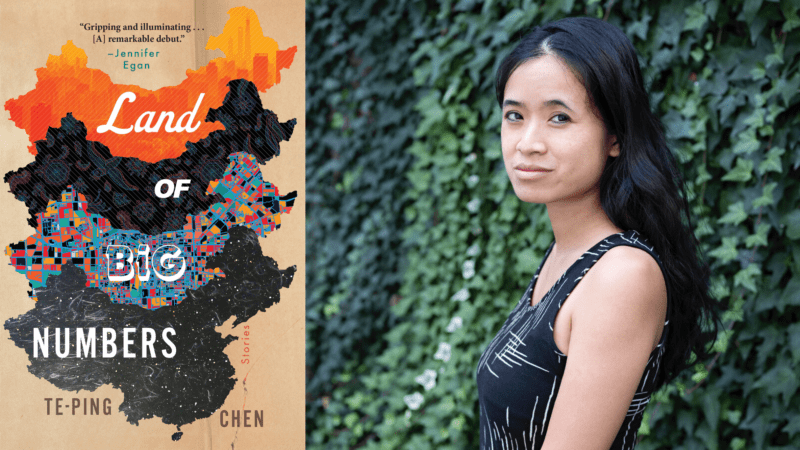

Te-Ping Chen, who spent six years in China, including two years in Hong Kong, as a reporter for the Wall Street Journal, found that her desire to write about that part of the world only multiplied the longer she was there. Though she loved her job, she felt limited by it: the rigors of journalism quashed so much of the peculiarity, the human weirdness, the everyday choreography that interested her. It’s these pursuits that animate the spirit of Chen’s first short story collection, Land of Big Numbers.

As I read, I wanted to see the characters that populate these ten pieces of short fiction gather, at a hotel or on a boat or at a dinner party. These characters include a brilliant young dissident and her twin brother, a champion video-gamer; an eccentric tinkerer and Party aspirant; a deranged inventor of romantic theme-park rides; an impressionable young florist; a teen investor high on the stock market rush; and a nurse with the worst hippie boyfriend. I wanted to see their specific, intricate personalities interact. Chen’s impulse to pull in for the close-up on characters who might otherwise be ignored somehow makes the scope of the world around them feel even wider.

Land of Big Numbers approaches character and emotion with subtle exactitude, but careens towards magical realism in its themes. One stand-out story is “New Fruit,” in which a novelty crop called qiguo—“a symbol of grassroots ingenuity” touted by the state media as “a new fruit that is a symbol of our new nation”—works as an allegory for collective memory. It’s Kundera by way of Barthelme, with a bit of a modern pharmacological spirit.

Chen examines a nation seized by the gravitational pulls of globalization, the internet, and new consumerism, but her writerly instinct stays under-the-fingernails intimate. She lets the forces of the world sneak in. The result is a collection of stories that’s impressive for holding tight to discrete moments in people’s lives, in order for us to feel how fast the world is spinning around them.

In her debut work, Chen’s voice is sensitive, quick, funny, and caring, and over the course of our phone call in February, her responses echoed this same sharp, clarifying precision.

—Maggie Lange for Guernica

Guernica: Do you know the trouble that your characters are going to get into before they do?

Chen: With the exception of “Lulu,” the first story in the book, where that character’s fate was just written into the conception of who she was, the rest of the experience of writing these stories was…Picture you’re standing in front of a sheet of paper that’s totally blank. And with every step you start to see a little more of what’s in front of you. You can move in different directions and it exposes different parts of the world around you—and you start to see colors and different shapes and people and activity. For me, all of the writing process was taking these tentative steps. Every story unfolded as a series of surprises in the writing.

Guernica: Tell me about ordering your short stories, particularly the final, punctuating story?

Chen: It was pretty intuitive, because there is such a different mix of styles: some more realist in tone, some inflected with magical realism; some more character-driven, and some with an ensemble cast; some are in the countryside, and some are more urban. In composing the structure, I was thinking about it as a mixtape, wanting to be mindful of tempo and the mood.

The one I was most conscious about placing was the final story. It’s grappling with some of the core questions gripping the book, and without too much of a spoiler, I liked that it contained an exit. I had a lot of affection for the protagonist of the last story. I loved her tenacity and the way that she ends up being the person asking questions. She’s not willing to follow a certain script. Though I don’t think she’s inherently an optimistic person, it felt important for me to end with a character whose actions in that story have optimism in them.

Guernica: Comparing your fiction writing with your journalism work, which tends to result in a more unexpected ending?

Chen: There are so many different ways you can be surprised as a writer. In journalism, you’re often surprised by reporting. You’re starting with a question and you set out to understand it better. You talk to a million different people and try to construct as much as you can as an answer. So much of how a news article is written and structured is stipulated by what the audience doesn’t know and needs to know. If you’re reading about headlines from China, like if you’re reading about America while overseas, it’s a truthful picture but it’s also a necessarily partial one.

Writing these stories was my own private source of joy, and an experiment for myself in a lot of ways. I wasn’t thinking about audience; it was really an enormous relief, getting to write without making everything you say perfectly accessible and economical and stripped away of anything except the absolute most functional parts of a news story.

Fiction allowed for so much more to be. I really felt like I’d spent so many years since I’d arrived in the country—first as a student in 2006—just storing up impressions and details and conversations, and feeling like the world around me was so urgent and compelling. And yet, I was only able to pour a fraction of that into my journalism. Fiction allowed for a much wider canvas; it gave me space for the unexpected. In so many ways, it’s about trying to create a world where you don’t know the answers and you don’t know the ending.

Guernica: Was your impulse always towards short stories as a form for this project?

Chen: China is a world that is multifaceted and complex and dimensional. In some ways, I couldn’t just pick one story.

Also, on a completely personal level, I started to write this collection while I was in the process of working on a novel. I’d just gotten stuck in this novel project. I was in the throes of revision and feeling like I’d lost some of that spark. Short stories were a chance to step away and play with another form I hadn’t experimented [with] before. They were a different kind of release.

Guernica: A couple of your stories have an uncanny resonance with some recent current events, particularly one about a heady stock-market fracas, and also one about forced isolation. Compared to reporting, do you feel like you’re in a more intuitive, maybe more predictive role with fiction?

Chen: Fiction can grapple with circumstances from a distance that can be difficult to comprehend. Part of the joy of writing fiction is you can draw on other tools to conjure this world, like magical realism, which found its way into the collection, partially influenced by hometown favorite Carmen Maria Machado. I use magical realism to conjure up life in a society where things feel over-the-top, and often surreal to the point of absurdity. Everything is just so charged and so propulsive.

My readers meet a supernatural fruit, or commuters stuck underground for months. All these have layers of fabulism—but at the same time, they’re woven in with other sorts of [real-life] details like funeral strippers or noodle-making robots. The real, mixed with the sense of the surreal, gives the feeling like anything could happen at any time, which does nearly sum up so much of the feeling of what it’s like to live in modern China.

Guernica: I have a pair of speculative questions based on your stories. In “On the Street Where You Live,” an inventor creates a ride that simulates the birth experience, advertised as a way to “Relive life’s original trauma!” and called “Tunnel of Love.” There’s an outpost in Atlantic City! Would you take the “Tunnel of Love” ride?

Chen: That one, I would not. [Laughs] No. No. No. Definitely not. I don’t like confined spaces, and it just sounds like a horrible experience. But I am sympathetic to its creator, who is of course an objectively unlikeable person. He has this distorted, often disturbing worldview, but in writing him I did end up feeling quite a lot of affection for him. In many ways he’s cosmopolitan, a global citizen, part of the Chinese diaspora living in Atlantic City. He’s just someone who has a sense of longing and desire for connection. We see that through his love of old Hollywood glamour, and his relationship with Lizette, and the way he comes up with these ideas for experiences in this theme park. While I would not like the Tunnel of Love, there are other ideas—not all carried out—that he evokes that I’d love to give a try.

Guernica: So he’s still a Willy Wonka for you, but not that ride.

Chen: He’s sympathetic. And at the end of the day, Willy Wonka was also really disturbing. He’s somebody who you also can feel empathy for, but he was also luring kids into his factory and having them killed off one by one with very little compunction.

Guernica: He exploited labor and conducted all these non-consensual experiments!

Chen: He basically goes overseas and imports helpless laborers who are locked inside this factory! It’s truly disturbing on a re-read.

Guernica: In “New Fruit,” you write about qiguo, a peculiar new fruit, with a velvety texture and pseudo-psychedelic effects. Would you eat the fruit?

Chen: In a heartbeat, yes. I feel like fiction can conjure up deep emotions and help us access experiences and memories and all these parts of ourselves that might have been buried. I think of the fruit as having a similar effect, and I would love to try it. The fruit is based on these nectarines I used to buy in my old neighborhood in Beijing, which were extraordinary. The real thing was delicious, and I would love to try the magical version, too.