Tom resumed his whitewashing, and answered carelessly:

“Well, maybe it is, and maybe it ain’t. All I know, is, it suits Tom Sawyer.”

“Oh come, now, you don’t mean to let on that you like it?”

The brush continued to move.

“Like it? Well, I don’t see why I oughtn’t to like it. Does a boy get a chance to whitewash a fence every day?”

That put the thing in a new light. Ben stopped nibbling his apple. Tom swept his brush daintily back and forth—stepped back to note the effect—added a touch here and there—criticized the effect again—Ben watching every move and getting more and more interested, more and more absorbed. Presently he said:

“Say, Tom, let me whitewash a little.”

Tom considered, was about to consent; but he altered his mind:

“No—no—I reckon it wouldn’t hardly do, Ben.”

—Mark Twain, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer

My mother names me for the son of the doctor who delivers me. This is the early ’90s, and the doctor in the room has short legs and a very white coat. Everything is starched: the nurse’s hair, the spic-and-span quadrant of floor, the doctor’s timbre of voice, the white, white coat. Everything moves with a humming efficiency. Mother has been here before. She is sweaty but unflappable. This second delivery proceeds at a pace that deters reflection—things are on their way, a husband taking calls in the hall, Clinton sweeping Arkansas then Alabama, words and news building and subsiding, the good doctor talking a lot about names. Mother begins to push.

The doctor has two sons: Tom and Jim. Either would make a fine American name he assures her, even though there is not really a metric for such things, and if my mother needs anything, it is a way of weighing the contents, of approximating density or speed, of saying this far on this much.

The name Jim already belongs to my mother’s lab director, a man who reads as sweet but essentially febrile. Tom, on the other hand, is clean of direct associations, yet rich in assumed cultural references. My parents are newly aware of Tom & Jerry, and Mr. Tom Selleck from Hawaii, and when they were college students in Hangzhou, they had read, in Mandarin first edition, of a Midwestern boy named Tāngmǔ Suǒyà who went toe-to-toe with Injun Joe and kissed Becky’s cherub cheeks by the wide, gracious Mississippi. It doesn’t seem like much of a choice really. They finish the paperwork and take their second son home to an apartment building shaped like a crumbling red Y, back into the May heat and the throes of my mother’s dissertation, a body of work she defends later that summer, standing before Jim and his bespectacled cronies in a polo shirt and wire frame glasses, chemical formulae parting in uncertain spools from her mouth.

All day and night their conversation bathes me, lathering my ears in the mixed quality of their speech. I don’t remember any of this, of course, though the present repetition of facts still stirs something in me, reaching out into a penumbral space I can’t explain.

And yet for the first two days in the hospital, I have no name, at least not in the language I know as my own today. Here we are: My parents holding and pacing. I cry only a little. All day and night their conversation bathes me, lathering my ears in the mixed quality of their speech (they come from different home dialects, different modes and classes of communication), the cooing of each 诺 and each 成, the blurred, gentle namings. On my wrist, a bright blue tag gives sex and mother’s last name: Boy, Luo. I don’t remember any of this, of course, though the present repetition of facts still stirs something in me, reaching out into a penumbral space I can’t explain, as it is preverbal, as it is pre-conscious, a story I can hear clearly but garble in every telling.

Months before my mother goes into labor, my parents settle on two characters for my Chinese name, two figures inscribing a hodgepodge of names I will spend my life growing in and out of. They call me Nuocheng (诺成), which reads as an allusion to Knoxville, Tennessee, a college town on the lap of the Appalachians where my parents are finishing their doctorates in chemistry. Specifically, Nuo comes from Nuokeshiweier, Knoxville’s Chinese isomer, while cheng is borrowed from Chengdu, the city in China where my mother spent most of her childhood and where her parents and brothers still live.

If you follow poetry news, you may know that Chinese names were a topic of vigorous op-eding last year. What was at stake is unclear or immaterial to most, but boils down to three Chinese-sounding syllables—Yi-Fen Chou—and how these syllables were taken and deployed by a middle-aged white poet from Indiana named Michael Derrick Hudson to get a poem published in Prairie Schooner. The poem in question, which Hudson/Chou titled “The Bees, the Flowers, Jesus, Ancient Tigers, Poseidon, Adam and Eve,” was well on its way to literary obscurity when it was picked, by Sherman Alexie no less, for the 2015 edition of The Best American Poetry. Alerted to his pseudonymous success, Hudson wrote to let Alexie, a prominent writer of Native American descent, in on his little yellow gambit. A period of editorial soul-searching ensued. As Alexie writes in a lengthy blog post on The Best American Poetry website: “In the end, I chose each poem in the anthology because I love it. And to deny my love for any of them is to deny my love for all of them.” So the poem was published, under Yi-Fen Chou’s imagined authorship, and if you buy the anthology today and flip back to Chou/Hudson’s bio, you can read about how “The Bees” was rejected from a slew of publications (Hudson kept very “detailed submission records”) when submitted under Hudson’s legal/white name, before eventually finding a home at Schooner under the aegis of an apparently Asian name. “If indeed this is one of the best American poems of 2015, it took quite a bit of effort to get it into print…” Hudson proclaims, pounding the pulpit for all the embattled white men writing under white names in today’s America.

As a writer of Asian descent, it’s hard for me not to take Hudson’s shtick a little personally, or to ignore the slew of media responses that have come out since, most of which have denounced Hudson as a tasteless appropriator, but none of which come out and say what really irks me about this whole matter. Because I have been thinking about this too much, because I am occasionally vindictive and usually self-involved, and because I am interested in how my own Asian-sounding surname might play out in the point calculus of what will or will not get you published, I have to wonder why Hudson reached, instinctively, for a Chinese name when the time came to exotify himself. I wonder why it was yellow that revealed itself as the most desirable, or convenient, shade: is it so easy, Michael, I ask this honestly, to write yourself thus pigmented, to transgress just that far, to play this game because you have (apparently) nothing to lose and much to gain in terms of accolades, and notoriety, and the embarrassment of a liberal literary establishment that has rejected you as who you are, which is to say white and entitled and a poet?

What emerges is an odd brotherhood, a kinship I discern in the abandonment of birth names, the taking of aliases. It is this happy betrayal that aligns us, that allows me to see him precisely as I see myself—smudged, a too-neat erasure of heritage and color.

I’ll admit that I am annoyed on many counts with Hudson, that I find his actions galling, and have talked shit about him while eating multiple tacos, spilling salsa down my shirtfronts. And yet I also admire him, for reasons I am trying here to understand.

Consider: For years I have misplaced or ignored my own Chinese name in the interest of making daily life in America superficially easier; I have never really regretted this. Thomas gets me through the roll call quicker. It is the name on my driver’s license, the sound I answer to in my head. And besides, I don’t need a Chinese-sounding name to inform the world of my heritage. Going by Thomas does not prevent people on street corners and in cafes from asking me, head cocked and expectant: But where are you really from?

Consider: Michael Derrick Hudson jettisons his white-sounding name to become Yi-Fen Chou, thus making a poem he wrote about Roman colossi and Christian idolatry more superficially interesting to diversity-minded editors (Alexie again: “When I first read it, I’d briefly wondered about the life story of a Chinese American poet who would be compelled to write a poem with such overt and affectionate European classical and Christian imagery, and I marveled at how interesting many of us are in our cross-cultural lives…”). The ruse works, spectacularly, some would say.

Consider: Both these choices, mine and Mr. Hudson’s, reflect a kind of brutal pragmatism, a hankering for results. Both involve a denial of one name for the potentialities of another. I admire Hudson for his pluck, the ease with which he slips identities, the way he can take on a Chinese name that roughly means a “piece of stink” and still end up in a prestigious literary anthology, the way he is unashamed of this. What emerges is an odd brotherhood, a kinship I discern in the abandonment of birth names, the taking of aliases. It is this happy betrayal that aligns us, that allows me to see him precisely as I see myself—smudged, a too-neat erasure of heritage and color.

A name can be, in the right circumstances, a catalyst. Said aloud, any name demands a response, sets in motion a series of events that can feel pre-determined, rote. Names are labels, little semantical handles we use to hold on. But handles open doors, and close others in their wake. Names divide hemispheres, cut characters out of history, draw our attention, immediate, fleeting, to the person, the place, the thing. And yet we are surprisingly careless in how we apply them. The process of naming can get away from us, until we find ourselves sowing labels willy-nilly, marrying them off, splitting and joining and hyphenating ourselves into a kind of chaos. “But where are you really from?” they ask, and I never know who to answer for, Thomas or Nuocheng? Who do they mean? Which part of me goes with each name?

As my mother knows well, scientists take a different approach. While I grow, embryonic in her womb, my mother stays busy in Jim’s lab, trying to modify a highly stable organic compound called adamantane into a more reactive form. The carbons in adamantane have what specialists refer to as a “chair” structure, a shape similar to that of diamond, in which the carbons align in four cyclohexane rings to make a kind of cage. Chemical nomenclature is tied always to such patterns. Each molecule’s naming denotes a specific number, type, and arrangement of atoms. In trying to alter adamantane’s structure, my mother is in a sense seeking a corresponding change in name. She sees it clearly, this molecule, how it looks, swiveling in dreamy, chimeric geometries, its hydrogens coming and going, every name just a temporary dalliance, a label always in the shedding.

For the first few years, my parents call me cheng-cheng and speak only in Mandarin. They are fresh out of grad school and house-shopping and I have an older brother they call nuo-nuo lying next to me in the powdery white crib. I remember the first day of kindergarten as the beginning of my American life, crying and pissing over the toilet, having to speak English all at once. I walk to Bluegrass Elementary hand-in-hand with my grandmother, who is dressed in paisley and Payless, her hair still black at the roots. The teacher, Ms. Jackson, calls me “Tommy Day” and over a red bin full of dry rice (they call these “sensory rice tables” apparently), I make my first friend, olive-skinned and ringlet haired, seraphic, the most beautiful thing I’ve ever seen.

Back home, in the starter house made of color pencil and framed in grass, my mother does laundry and writes papers about modified adamantane cages and waits for certain names to stick: Carol at the lab; John the dentist; Dan who sold us this house; Tommy and David and Huimin pronounced the American way.

Debra, the lab secretary and my mother’s best white friend, starts to send my parents invitations to Sunday services. Some evenings after school, I can hear them downstairs laughing about things I don’t understand. The television shimmers to life, that clarion music bringing Peter Jennings with the nightly news. Tommy-eh, she calls from the base of the stairs when the rice is done steaming: Xia lai chi fan!

For a couple of years, I move from place to place. There is a long summer in an apartment in Oak Ridge with ladybug carcasses all over the sills and a mattress on the ground that my brother pushes me off of at night. One day, playing hide-and-seek with a neighbor girl, I shut myself by accident into the crawlspace at the foot of the stairs and can’t get out. The air inside is stale, rarely breathed, and for a moment I sit in the darkness on the verge of tears, calling for the girl. And yet panic never quite sets in. I hear my parents returning from their daily walk, a rhythm coming to me from across the wet grass and through the dragonfly air, and already the darkness is opening up, the neighbor girl heading on home, the upstairs apartment and its miasmas receding. It is all so obviously temporary, a prelude to the big, airy house in the suburbs, to the baseball printed wallpaper and corduroy recliners, my baby sister delivered in shades of pink.

In my new neighborhood, the boys and girls call me flatface, which is fine, because every kid on the school bus has one stupid nickname or another, and mine seems accurate enough. My best friend at the time is three years older and named Michael. He’s cool and dauntless and a swimmer on the summer league, fair-skinned and freckled. Every Sunday, Michael calls the house wearing an Asian accent and asks if mother is making fried rice again.

By high school, I am telling my mom to call me Thomas, not Tommy-eh, and the American Dream is embodied by a blonde boy wearing Hollister flip flops who calls me Chinky and is my best friend. It’s not important who comes up with this name. What’s important is that he calls me anything at all, that he forms these syllables and means them for me. Weekend after weekend, the American Dream invites me to sleep over at his mother’s home in the neighborhood by the train tracks and the too-green lake, and in the interim, I/Chinky become relatively less invisible at school. I join the cross-country team and help neighbor girls pick out dresses at the West Town Mall. I do well in all my classes but try not to make a big deal about it. The problem (and the fear) is always the Asian kid down the way with no name and few friends. I dislike this person, disown him before he can do the same to me. I get properly drunk for the first time after a math competition one spring, and sit with the future prom king on his couch the next year watching Brokeback Mountain and eating ice cream. When senior year comes, I will be nominated like all the other Asians for “Most Likely to Succeed” but end up winning “Best Dressed” instead, a change in the program notes that feels like validation.

But before all this, the blonde boy who is the American Dream turns sixteen. He throws a party at the house by the train tracks and the too-green lake. A few weeks later, I stop talking to him, for reasons I can’t quite grasp at first. My now ex-best friend spreads around that I gave him head under the covers that night, and that he wouldn’t have “let me” had he known I was going to take it so seriously. I’m pissed, but what I let him do is continue thinking this way, because it’s logical and almost correct, because the real shame in this instance is not sexual but lexical and therefore unworthy of language. The truth is that I have grown to hate this sound, Chinky, which he and his family make with affection. I can’t believe how close I’ve let the name get, bleeding straight into my slushy sense of self. My parents have heard him call me this, I think, cringing. They’ve seen me perk up like a dog, and run.

And in the end, what happens? A chemical shift, a change in structure. People forget. I move far north for college. The American Dream occasionally flickers back into view, but always at a distance. A few years’ later, at a holiday party near my parents’ old Southern campus, I straddle his lap and kiss him against a port-stained futon, but it means nothing—just a reintroduction, a name I don’t own anymore.

In naming us, my parents had unwittingly tracked their own trajectory and ours as well, telling a story, not of sentences perhaps, but still gravid with meaning and grace and a strange, atheist faithfulness: Nuocheng, Nuoou, Nuohang. Mother City, Father River, an Origin Shared.

I read once in a Mark Twain story that “fancy is not needed to give variety to the history of a Chinaman’s sojourn in America. Plain fact is amply sufficient.” The “facts” that Twain goes on to relate in this story are typical of the disillusionment and barbaric treatment that early Chinese immigrants to our country experienced at their arrival. The protagonist Ah Song Hi, recently come from Shanghai, writes to his friend Ching-Foo of being beaten and kicked by police, mauled by dogs, thrown in prison and extorted for money he did not possess, cursed and scratched by prostitutes, placed on trial but unable to testify on his own behalf, sentenced, and put away. It is a litany of miseries that today feels more than anachronistic, for the facts have most definitely changed, and reading such work as a Chinese-American today feels like encountering yet another re-imagining of who you are, not a historical fact but a yellow-tinted image on a white, white sheet.

Recently, I met a man at a bar who took me home and, mid-undress, asked me to tell him my Chinese name, and though I am wary of this question and the assumptions it makes—real or imagined—about my background, this man seemed sweet, and genuinely curious, and so I told him the usual spiel and then spun it out longer. I told him that my name, Nuocheng, combined the first sounds of Knoxville, the city I was born in, and Chengdu, the large and languorous metropolis in western China where my mother grew up. I told him that my older brother, Nuoou, was named in a similar fashion, with the nuo coming from Knoxville and the ou from a river, the Oujiang, in my father’s hometown, while my sister, Nuohang, derives her name from Knoxville and Hangzhou, the Chinese city where my parents met and married before they left for America. And as the man and I did what we had come to do, little lights started to go off inside me, points on a map I could see clearly now: In naming us, my parents had unwittingly tracked their own trajectory and ours as well, telling a story, not of sentences perhaps, but still gravid with meaning and grace and a strange, atheist faithfulness: Nuocheng, Nuoou, Nuohang. Mother City, Father River, an Origin Shared.

In college, I lived almost exclusively with other Chinese-Americans. This was not a choice I consciously made, to pick roommates who had similar backgrounds, but it happened, and though I had no intentions to racialize myself, to become somehow more Chinese, I was interested in people who had a similar set of references to me, whose parents were also from the same, albeit massive, country, and who understood the strange hybrid language (“Chinglish,” we called it) I spoke at home.

One fall, I biked across campus from the biology labs to take a course in Asian American Literature. The professor was a Korean-American woman with a Ph.D. in English from Stanford. She wore a camel colored skirt suit and tapered black pumps. Her reading list included the usual suspects (Maxine Hong Kingston, Chang-Rae Lee, Jhumpa Lahiri) but also names I hadn’t seen before (Nam Le, Agha Shahid Ali, Pimone Triplett). There were maybe one or two non-Asian students in the seminar. Collectively, we seemed like a capable group, shiny and well-wrought, assembled from various corners of the country and world, snappy dressers in cashmere and tortoiseshell. Professor Kim would speak, and we would follow, rattling off quotes from our close readings, little theses we carved out from the text.

Later that season, as a hurricane touched down in New York City, I would sit with a friend in an empty dining hall, telling her about my class and how sadly predictable I found its demographics, to which she responded by saying that it was difficult for her (white and forcefully erudite) to see herself in ethnic literature: “I’m not saying it’s not good, just that it’s geared towards a specific audience.”

One of my great fears is that my reader will think I have forgotten my own set of privileges, the positive side effects of having an Asian-looking face and Asian-sounding name in today’s America.

I sat on that comment for a long time, trying to remember all the books I had been assigned in high school English courses, that steady diet of Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Bronte, Orwell, and Woolf. I thought of how easy it had been for me (Asian and bookish) to traverse certain imaginal boundaries; to wish myself into white bodies staring at lighthouses and kissing men named Heathcliff; to watch a lambent bell jar descending and a green light flashing at some pier’s end; to dream that dream of blonde hair and British seacoasts. And then I thought of all the books on Professor Kim’s syllabus, the fact that I could barely think of any Asian authors she had missed. I saw suddenly before me a shallow pool that I was pipetting steadily into my brain, a tiny assemblage of unpronounceable names that stood for a generalized Asian-American experience, an experience I was also, perhaps, supposed to write about, to sift and parse and duly abandon: It’s a bit too Amy Tan, no?

When college ended, I went, predictably, to China, where all my family’s names pointed. I went to Wenzhou where the Oujiang runs free, ate lunch on a sunny college campus in Hangzhou, took endless walks through Chengdu, thinking how strange and yet pleasant it was to be this city’s namesake and to run by its tree-lined canals or ride its alleys side saddle on the back of a friend’s bike. For a year, I traveled to these places and many others, and everywhere I went, locals would introduce themselves and ask to know my name. Thomas, I would say, pronouncing it toe-ma-shi. If they were educated, and many of them were, they would often inquire: Thomas? Xiang Tāngmǔ Suǒyà?

Dui, I would answer, just like Tom Sawyer.

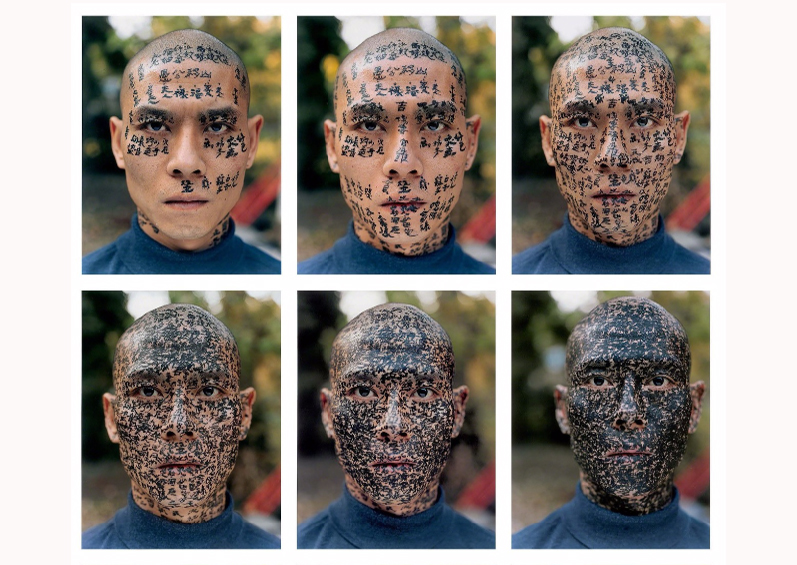

I think in the end it’s about how easily it came to him, how he simply reached out and took one from the batch. There is something to be said for learning our names as we go, for treating them not as static forms, but as boxes we live in briefly, chemical signatures to be made and remade. It takes work, figuring a name. It’s not something you pluck unformed from the ether, as Michael Derrick Hudson did. You have to ease into it, this funny little domicile, and feel your way blind to the foundations. According to the U.S. State Department’s report on such things, the Chinese language is one of the hardest to learn. This is because each sound can be split into four separate tones, creating a diaspora of meanings. My nuo is not just the nuo of Knoxville; my cheng not just a rendering of the city in China my mother came up in. Looked at another way, the nuo in my name implies nuoyan, a phrase that essentially means a promise, while the cheng can also come from chenggong, which translates to success. Take my name and say it slow: a hometown, a geography, a half-baked promise to succeed.

Tom gave up the brush with reluctance in his face, but alacrity in his heart.