“So what is it that I do? I collect the everyday life of feelings, thoughts, and words. I collect the life of my time.”

—Svetlana Alexievich’s Nobel lecture, 2015

The Prize

O

ctober 8, 2015. It was mid-afternoon in Sweden and the Nobel Foundation was about ready to do its thing. The world’s media was waiting to publish one of two stories—either congratulations or apologies to Philip Roth, or Haruki Murakami, or Adonis. Or, maybe the Foundation’s recent penchant for awarding the world’s most prestigious literary prize to someone relatively unknown in the States would strike again. People were even watching the live stream. Well, me. I was watching the live stream. That magical moment you find in theaters or concert halls arrived—all the ambient noise suddenly crested and then fell into silent anticipation. The door opened and flashbulbs started almost simultaneously. Not being fluent in Swedish, I listened for whatever was obviously a name. Was it going to be Roth? DeLillo? The last American was Toni Morrison in 1994. Right before Ladbrokes closed the bets, the odds favored Svetlana Alexievich, a Belarusian journalist and writer. Her entire body of published work was five volumes, only two of which had been published in the United States.

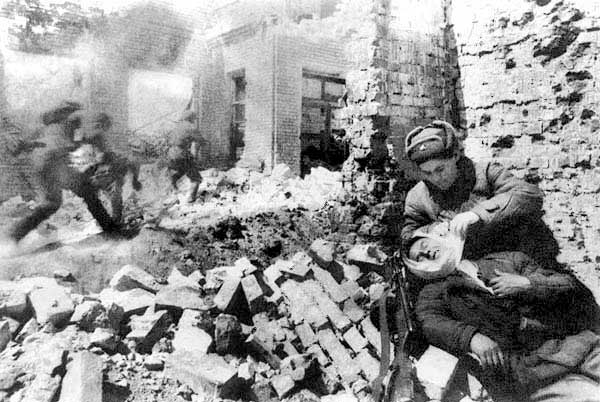

The bettors were right: the 2015 Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded to Alexievich, “for her polyphonic writings, a monument to suffering and courage in our time.” In a somewhat unfair but not entirely inaccurate rendering, the New York Times’ Rachel Donadio deemed Alexievich “the Nobel Laureate of Russian Misery.” Though her work seems to have a through line to sadness of a marrow-deep level, there is also much joy, love, humor, and a sense of the marvelous in each of her oral histories.

War + Remembrance

As of next year, Svetlana Alexievich’s entire oeuvre, thus far, will finally be available in English. It can be seen as divided into two very distinct periods, which nevertheless exist in conversation. A reader can’t begin to grapple with the magnitude of Alexievich’s project by reading just a smattering of the books, or fully comprehend it without reading them all. In fact, a reading in proper chronological order (historically speaking) cracks something stark but wonderful wide open—nothing less than a spotlight on the Russian soul, national, cultural, romantic, religious, and otherwise.

Before getting into each of the four books currently available in English, it’s worth understanding the approach Alexievich brings to whichever subject is at hand, the quest she has pursued throughout her career:

In each of us there is a small piece of history. In one half a page, in another two or three. Together we write the book of time… it is precisely there, in the warm human voice, in the living reflection of the past, that the primordial joy is concealed and the insurmountable tragedy of life is laid bare.

For Alexievich, the investigation of that place where the joy and tragedy commingle and inform each other has been her focus since she began work on her first book in 1975.

This July, that book, translated by the powerhouse duo of Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky, was published in the US for the first time. The Unwomanly Face of War: An Oral History of Women in World War II is a massive accomplishment, and provides both an occasion and an incredible lens through which to view the rest of Alexievich’s work and the Russia she has unearthed and restored. We get to look over her shoulder as she digs deeper and deeper, towards the center of her project and, really, her world—Homo sovieticus, or Soviet “Man”—by virtue of chronology. With this book, Alexievich’s long game becomes clear as the Russian century snaps more sharply into focus.

The Unwomanly Face of War opens with a section entitled “A Human Being is Greater than War.” Comprised of excerpts from Alexievich’s journal between 1978 and 1985, this serves as a fascinating précis of not just the work to come, but the works that follow. As a result, this underscores her belief that the book of time is written together and, in turn, makes any reading of her work a kind of partnership.

By determining how people shirk gender, class, and so on in an effort to participate in Russian life, there’s a greater sense of what’s at stake, and what motivates the Russian people. For Alexievich, it isn’t enough to merely tell the story. The actual shaping of the narrative, and its reception, is of equal, if not greater, significance.

We are all captives of “men’s” notions and “men’s” sense of war. “Men’s” words. Women are silent.

Whether it’s “men’s notions” or the male gaze, Alexievich works to subvert a masculine narrative. With The Unwomanly Face of War, she introduces the alternative to a readership in an act of defiance and bravery. She doesn’t negate the accepted and perpetuated male narratives of martial victory, pride, and loss. Instead, she chooses to tell of a different experience all together. For men, as Alexievich sees it, “the history of the war had been replaced by the history of the victory. Women, however, do not have that luxury.”

Women’s stories are different and about different things. “Women’s” war has its own colors, its own smells, its own lighting and its own range of feelings. Its own words. There are no heroes and incredible feats, there are simply people who are busy doing inhumanly human things.

In each of her books, Alexievich works in the mines and furrows of human experience, teasing out a variety of voices in direct reference to one seismic event or period. She rarely puts herself in the narrative, letting these voices speak for themselves, intervening only to locate them in the most honest light and maximize their impact. Alexievich does this so deftly that it seems as if those speaking have placed the book personally in your hand, its form and power generated organically in the exchange.

A key component of each of the testimonies Alexievich has collected is endurance. Not to be mistaken for flat-out suffering, it is, instead, a choice. A choice to stay where one’s family has lived for generations, a choice to flout protocol and hold the loved one who’s been exposed to radiation, a choice to resent what’s occurred in Afghanistan ostensibly in your name, or a choice to be a woman on the front line rather than Mrs. So-and-so-ivich back home. It is, most importantly, a choice to bear witness, to understand the unique experience that was to be Russian in the twentieth century. The hardship, the beauty, the depravation, the community, the fear, and the laughter that blended too easily into tears. Alexievich is a portraitist of Russian life, highly attuned to the full breadth of that spectrum. The red of blood splashed across the snow is very different from the red of grinning lips against white (if often stained) teeth.

The book that followed The Unwomanly Face of War, The Last Witnesses, out in English (and also translated by Pevear/Volokhonsky) next year, focuses on testimony from those who were children during World War II. Her next, Zinky Boys: Soviet Voices from the Afghanistan War, was the first translated into English in 1992. Like The Unwomanly Face, it, too, opens with a gendered consideration of war being teased out in Alexievich’s diary entries:

I didn’t want to write about war again, let alone one actually in progress. There’s something immoral, voyeuristic, about peering too closely at a person’s courage in the face of danger…. I can’t rid myself of the feeling that war is a product of the male nature. I find it hard to fathom.

There’s a kind of spiritual exhaustion evident in this, but it doesn’t stall Alexievich. Quite the opposite, in fact. It spurs her to explore why the story is worth telling in the first place. Zinky Boys is important because, tonally, the nationalism evident in Unwomanly Face is significantly reduced. Whereas soldiers in the Red Army felt a strong sense of duty and obligation to fight—and had the support of the Russian people—by the time of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, it had given way to confusion and resentment.

We have this image of the soldier returning home in 1945, loved and respected by all…. But these soldiers back from Afghanistan are something else—they want American jeans and Japanese cassette-recorders. You know that saying: Let sleeping dogs lie? It’s a mistake to ask more of human beings than they can humanly be expected to give.

In her consideration of combat in Afghanistan, Alexievich offers testimonies that swirl around why we fight, what we fight for, and how one can meld pride with the indignities of war. At the close of Zinky Boys, she receives several different messages (written, telephone, and otherwise) addressing the book and its contents. One in particular sums up Alexievich’s mission perfectly:

I shan’t read the whole book, because of an elementary sense of self-preservation. I’m not sure whether we ought to know so much about ourselves. Perhaps it’s just too frightening. It leaves a great void in my soul. You begin to lose faith in your fellow-man and fear him instead.

This is the End

It took nothing less than the rending of a world for Alexievich to move away from combat to the quieter battlefields of societal decline and spiritual collapse. Though Zinky Boys came out four years after the Chernobyl explosion, Alexievich spent the next seven years following the publication of Zinky Boys, researching and writing about the defining post-WWII nuclear disaster.

Voices from Chernobyl, nimbly translated by Keith Gessen, marked a new height for Alexievich. Her “cast” of voices is larger and her subject more defined, more excruciatingly rendered. She didn’t seek out this subject, as she had with Afghanistan and the records and memories of World War II. She didn’t need to. She could have done nothing at all, and still the waves of unrest generated by Chernobyl would have swelled around her. But of course, to sit there and wait isn’t her way.

Though the three books that preceded it are massive and affecting, Voices ushers in both the elemental and the intimate. Mapped against the aftermath of Chernobyl, and including testimonies covering everything from minutes to months to years after the accident, there’s a more (or differently) rooted quality to it absent in the previous work. Gone are the stories of armies and concerns of nationalism. Instead, Voices opens with a simple and devastating query: “I don’t know what I should talk about—about death or about love? Or are they the same?”

The scale of the disaster is commensurate with war but the responses to it are grounded not in nationalism or duty, but a need to cope, to grasp the unknown and unknowable. The enemy became change; the land and custom the Russians once knew was no longer theirs for the taking. Lives were lost, destroyed, quarantined, buried. One could barely understand it, let alone combat it. Unsurprisingly, Alexievich was aware of this transition. In her epilogue to Voices, she writes, “I used to travel among other people’s suffering, but here I’m just as much a witness as the others. My life is part of this event. I live here, with all of this.” With Voices, Alexievich’s role changed. She had to record what was happening in the world as it was happening. She still spoke to others, but her own account started to take up more space.

On Love and Aging

Vladimir Putin’s grandfather was Stalin’s chef. Let that sink in for a second as we consider the most recent and most lauded of Alexievich’s books, Secondhand Time. It is her magnum opus, so far at least, fusing the intimacy of Voices of Chernobyl with the interest in nationalism and geopolitics seen in the earlier books. Taking nothing smaller than the decline of communism as her focal point, Alexievich collected interviews for twenty-one years, from 1991 to 2012, making it her longest project.

The first words of Secondhand Time say it all: “We’re paying our respects to the Soviet era.” The next 450-plus pages shed light on the books that came before, but also chart the path from the post-Soviet era to the Russia we are back to worrying about today. For Alexievich, the presence of Putin, and the autonomy he wields at the helm of a country that hasn’t been viewed objectively for nearly a hundred years, is the real problem. In her New York Times interview, Alexievich directly addressed the West’s misperception of Putin. “They do not understand that there is a collective Putin consisting of some millions of people who do not want to be humiliated by the West…. [T]here’s a little piece of Putin in everyone.” Never a big fan of Putin’s, a feeling that is mutual, Alexievich has used the platform afforded by her Nobel win to speak against Putin and his politics.

At a press conference after the announcement, she said, “I love the Russian world of humanities, the world that the rest of humankind is still in awe over…. However, I do not love the world of Beria, Stalin, Putin. That is not my world.”

Her world is one worth discovering and investigating. Her gifts are sui generis and reading her not only makes you a concerned and more vital political participant, but a concerned and more vital person. She is not just a stuffy, inaccessible Nobel laureate but, instead, a poet of people, a composer of inordinate skill writing chorales of community.