You can hear the boats go by, you can spend the night beside her

And you know that she’s half-crazy but that’s why you want to be there

And she feeds you tea and oranges that come all the way from China

— Leonard Cohen, “Suzanne”

Suzanne Verdal told me she could make me famous. “Be ruthless, be ambitious. For both of us,” she urged, her onyx-colored eyes not just big, but almost manic in their largeness. If I did her tale justice, Suzanne said, I could put us both on the map. And that’s how I found myself sitting in a diner in a forgotten mountain town along the California/Oregon border, trying to convince Suzanne to let me record our conversation. She eyed my phone with suspicion, then waved her hands over me like some kind of enigmatic clairvoyant and promised that if I stick with her, only great things could come my way. Mesmerized, I thought, Where do I sign up?

When my father played Leonard Cohen’s music for me as a child, Suzanne — the inspiration behind Cohen’s indelible song of that name — was who I wanted to be. She was my first understanding of what it meant to be a “muse,” and she imbued the role with a rare kind of power. In the song, she’s a force to be reckoned with, leading an entranced Cohen to a place of deeper understanding by illuminating the grace in the wreckage that’s all around them. Cohen depicts her as a woman whose beauty, mystery, and joie de vivre drive him to some of his greatest artistic heights. That ability struck me as enviable and romantic; I wanted to hold that kind of sway. Long before I knew what Suzanne looked like, I identified her with the woman depicted in the illustration on the back of the 1967 record Songs of Leonard Cohen. Dark haired and nude, she was emerging from violent flames and wearing chains around her wrists. It was a stunning, startling image that fused beauty with captivity. At the time, I didn’t question that equivalence: I dreamed of being in the spotlight, and I used to fantasize about what it would be like to pose for the image.

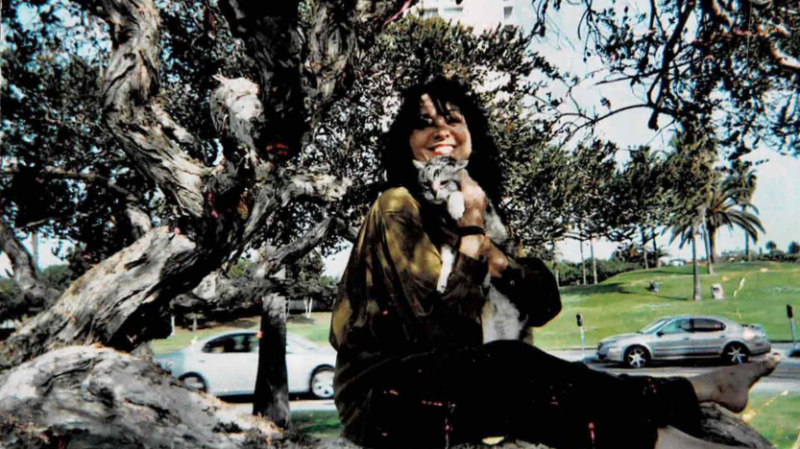

As I got older, there was a shift in the way I understood Suzanne: I longed to be the artist instead of the inspiration, and wondered if she was actually a prisoner of someone else’s success. It was a friend’s father who first told me about the real Suzanne. A photographer, he’d met Suzanne when he took pictures of her dancing at a drum circle in Venice Beach in the early 2000s. He described how her life had a taken a bleak turn, how her dream of being a famous dancer had never materialized. Before that, I had no idea Suzanne even had artistic aspirations; I hadn’t really thought about her life outside the song. But Suzanne’s story, as my friend’s father told it, felt depressingly familiar. Despite the powerful spell she cast on Cohen, Suzanne seemed to be one in a long line of women who had been defined by a man. I didn’t want to believe it.

So I spent months tracking Suzanne down, trying to convince her I was the person to set the record straight. I told her that I wasn’t interested in Cohen, but in what she had gone through — and that I hadn’t seen anything written or made about her by another woman who could understand the weight of what she carried. I imagined I could help unshackle her from the complications that come with being a famous muse and reveal the real person beneath the myth. It turned out that that was the last thing she wanted.

She gets you on her wavelength

It’s May 2019 when I meet Suzanne at a Black Bear Diner in Yreka, CA, a downtrodden town best known for its association with the California Secession Movement. The diner is a chain restaurant catering to both families with small children and truckers looking for something better than Burger King. Suzanne’s long hair is dyed a matte black, and she wears it piled loosely atop her head, held together with a bright blue scarf. Her matching taffeta coat has a petaled collar that blossoms around her face, making her look like an Elizabethan lady with a neck ruff. Still so beautiful, it’s hard to gage exactly how old she is, and she refuses to divulge. “I never tell my age,” she says, with a dramatic wave of her hand. “Not even to my cats.” At her elbow is a man she calls her “agent.”

David Nigel Lloyd wears a white linen suit of the same shade as his long beard, and a bolo tie with a turquoise stone at the center. On his head is a large cowboy hat. He tells me he’s an adjunct professor at the local community college. “You might mistake it for a prison,” he says jovially, chuckling a bit at his own joke. I realize that more than anything, Suzanne wants a witness: Lloyd is there in case I’m not who I said I was.

Suzanne is mistrustful of me, and it’s taken a lot to get to this diner in the first place. Months before, as I put my pitch in the mail to her as she had requested, I’d thought about why I was so determined to meet and write about her, despite her skepticism. Mostly, I was driven by anger. Anger that arose from feeling dismissed by the male artists I knew — in grad school workshops, at parties where they talked right past me, even in my dating life. Like Suzanne, I had a history of getting involved with powerful, older men whose success I desired, even if my desire for them was on shakier ground. Suzanne would be my equalizer: Her story would help me become a peer of these men, rather than just another lit girl in black tights hanging on their every word as they dissected the latest issue of Harper’s. In Suzanne, I saw the possibility not only of reckoning with what muses might be owed, but the chance to strike a blow for all the women who have inspired men’s art while struggling to be recognized for their own.

Almost immediately after we introduce ourselves at the diner, Suzanne launches into a rant, listing a set of grievances against those who have done her wrong, starting with her dance community in the ’60s. “When I was doing very avant-garde modern dance, other dancers would steal my ideas,” she says. “Although they would laugh at me at first, or say ‘Oh, you’re doing that weird dancing now.’ I felt very betrayed.”

As she continues, it becomes clear that Suzanne believes much more than her choreography has been taken from her, that she’s been robbed of her story and her name, and maybe even her sense of self. Poached, by every journalist hoping to gain more insight into Cohen’s psyche. By every Montreal establishment that still uses Suzanne’s myth to lure in tourists (one, Bar Suzanne, boasts a “Cohen Daquiri” on its cocktail menu). By the woman who, Suzanne tells me, once claimed to be Suzanne and then sang her namesake song with Peter Gabriel in France. Perhaps even by Cohen himself — and by extension, I imagine, all the men who were intoxicated by Suzanne but never really saw her.

She lets the river answer

Suzanne recalls being introduced to Leonard Cohen in the mid-sixties by her then-boyfriend, the sculptor Armand Vaillancourt. She was seventeen years old, just out of high school; Vaillancourt and Cohen were both in their thirties. Cohen and Suzanne shared a platonic attraction to one another, and spent days walking up and down the St. Lawrence River in Montreal, waxing philosophical about life and art. Their relationship was never romantic, but as Suzanne remembers it, Cohen was fiercely protective of her, even having words with Vaillancourt about his indifferent, at times cold, behavior towards his younger girlfriend.

When Suzanne tells me about Montreal in the sixties, she paints a portrait of a city at the dawn of a cultural revolution, awash in creative happenings. Bordering tenuously on the cusp of adulthood herself, Suzanne believed back then that art meant something, while money meant nothing at all. With a body that was lean and strong, and a back she could bend in an arch as round and as dangerous as a bow, Suzanne’s dancing and choreography skills were the only currency that really mattered to her. A fixture on the bohemian scene, she describes constantly fielding invites to the best, most elite clubs: the Pam Pam, Le Vieux Moulin, and Le Bistro, styled to look like a Parisian cafe.

In her first big break, she was booked to dance on national television. She performed in silver lamé as an homage to Marlene Dietrich, whom she had once seen in the flesh while working at the front desk at the Ritz Carlton Hotel. Almost six decades later, Suzanne’s face lights up with a mixture of awe and pride as she recounts how Dietrich had walked down the stairs of the hotel, decked out in furs that trailed to the ground and holding a small, yapping dog in her arms. Meeting Suzanne’s gaze, Dietrich looked her up and down, and for a split second it was like Suzanne glimpsed her own future. Later Suzanne choreographed at Expo 67, Montreal’s international fair, where she instructed her dancers to paint their faces in white makeup and wear black unitards with white stripes down the arms and bodies. In photos, the dancers look uncannily like a Keith Haring painting — though this was years before Haring burst on the scene.

It’s not entirely clear if it happened months or years after she and Cohen first met, but eventually the musician would create an enduring myth around Suzanne — who, in spite of her dancing and her ambitions, was also half Cohen’s age, soon to be pregnant with Vaillancourt’s baby, and living on the edge of poverty in a studio near the river.

You want to travel with her

Cohen first wrote “Suzanne” as a poem, and had no intention of turning his ode into a song. In fact he didn’t think of himself as a singer/songwriter at all; he was an author on the brink of publishing his second novel, Beautiful Losers. It was through the encouragement of his good friend, Judy Collins, that he began looking at the poem as lyrics, and it was Collins who first recorded it, on her album In My Life. One year later, in late 1967, Cohen’s rendition appeared on his own breakthrough record, the release of which transformed him almost immediately from middling writer to full-blown folk god. Yet, in a contract he didn’t have the wherewithal to read, Cohen signed away the rights to “Suzanne,” ensuring he would never make any money from the song. “The rights of it were stolen from me,” he says in a video of an early performance. But he claimed the theft didn’t bother him: “I felt that was perfectly justified because it would be wrong to write this song and get rich from it too,” he explains, as the audience vigorously applauds. In the end, though, Cohen did get rich. By the time he died at age eighty-two, the day after the 2016 election, some sources estimated his net worth at forty million dollars.

Suzanne, on the other hand, has spent nine years of her life homeless, living out of a caravan-like truck that she built with her son, Kahlil. Currently, she resides in a one-bedroom shack only a few miles from where we meet at the diner. She struggles to find the couple hundred dollars she needs to pay rent every month. “I need to find a way out,” she tells me from her perch on the vinyl-sided diner booth, hands scrunched into fists. “The concrete floors are terrible for my back.”

She also wrestles with the consequences of her distinct gift: her flair for divining greatness in other young artists. This ability, she tells me, has been her best asset as well as her heaviest burden; in return, she forfeited her own ascent. “I would say, ‘Oh my gosh, you’ve got so much talent, why don’t you think about doing that? Lo and behold, five years later, they’re doing it, and ten years later, they’re famous,” she says. “I seem to have that insight, but the cobbler has no shoes. I’m not always good for myself.”

It’s not only Cohen whom Suzanne understands she has inspired. Armand Vaillancourt has had a long and prolific art career; his publicly commissioned Vaillancourt Fountain is displayed prominently in San Francisco, and Suzanne thinks it was her influence in the early days of their relationship that helped Vaillancourt grow into the artist he is now. When I exchange emails with Vaillancourt though, he doesn’t mention this — or Suzanne’s dancing, or even the child they had together. He simply writes, “Suzanne was a beautiful woman, you know.”

In the late seventies, while Suzanne was dancing on the renaissance festival circuit in Minnesota, she became good friends with a woman whose eleven-year-old daughter would grow up to be the writer Cheryl Strayed. Suzanne showed me her copy of Strayed’s memoir, Wild, which had a thoughtful inscription from the author inside. In an email, Strayed remembered Suzanne as “magical and powerful.” “Her vibrancy took my breath away,” Strayed wrote. “She struck me as a very strong woman and her creative approach to life reminded me of my mom (even then). My sister and I were utterly enchanted by her. Years later, when I learned she’d inspired the song, I could imagine exactly how that could happen.”

Strayed sends me a photograph of herself with Suzanne. In it, Suzanne’s eyes glitter and her hair is like a giant halo; her collarbones glisten beneath a heap of silver necklaces.

You want to travel blind

Sitting next to her at the diner, David Nigel Lloyd is the latest in a long line of men Suzanne has trusted to protect her: many of them do so more than willingly. I see Suzanne’s effect in action later that afternoon when she meets my boyfriend. “Well aren’t you just a strong American hero,” she says, putting her hand on his arm. His eyes light up.

If men have been Suzanne’s greatest necessity, they’re also the driving force behind her physical deterioration. Suzanne relates her accident, one of her most traumatic experiences, back to a man — an experience that marks a before and after in her life. She holds back tears when she talks about it. But then she puts it bluntly. “It’s like dying,” she says. “You’re never the same after that.”

When it happened, Suzanne had been living in the US, teaching movement to actors in the same LA studio where Marilyn Monroe took her first classes. She also had a nice side gig going as a massage therapist. But she wanted to come to Hollywood to try her hand at choreographing and dancing in music videos. Back in Montreal, Suzanne had had her own dance studio, but she had longed for something bigger, something a bit more center stage, and so she had packed up and moved to Hollywood to see if she could make it on the small screen. Though she was then already in her fifties, most people thought she looked much younger. From photographs she showed me of that time I can see why.

She shacked up with a man who she knew in her gut was a bad guy. He bullied her constantly, but he also made her feel safe. While living together, she called him her “roommate” though sometimes he was also her “boyfriend.” He was paying the rent. He was mad that other people connected with her, that he couldn’t have Suzanne all to himself.

Suzanne claims that he said he had repaired the ladder on her truck. But when she climbed up, the ladder came loose, throwing her backwards toward the concrete. She put her hands out to break her fall. Without that catch, the doctors said she would have been paralyzed. But in protecting herself, she sacrificed her wrists, breaking both of them, one in three places that required the insertion of a metal rod. A bone in her lower lumbar broke, causing her vertebra to slip forward, eventually affecting all her organs. Talking about it, Suzanne puts her head in her hands, near tears. “Concrete has no bounce, no mercy; it’s completely unforgiving.”

As her tale turns, she stiffens, and her words become almost monotone. After the accident, Suzanne’s boyfriend put her out on the street. He didn’t care that she couldn’t work, she says, or that she’d never dance again. The hospital bills mounted, and suddenly she had absolutely nothing: no man, no apartment, and no money. Thankfully, she still had her camper, in which she’d spend most of the next decade driving up and down the coast looking for safe places to sleep.

Years ago, while parked in a Santa Monica parking lot late at night, Suzanne heard her cat Pookie hissing. When she got up to investigate, she saw the dirty fingers of a wild-looking man trying to push her window down. Suzanne jammed the keys into the ignition and got the hell out of there. She found another parking lot, and double-checked all the locks. Suzanne wanted to believe she was safe, but it was only another parking lot.

Since then, Suzanne has tried to make every day a fresh one: clean linens, tidy hair, nice clothes. She never wanted people to know the depth of her situation. “The stigma of being homeless is no joke. People look down on you and think you must be a drug addict or a hopeless loser to be in such a situation,” Suzanne says. “It was very tough on my honor and my dignity.” She wanted them to watch her dancing on the beach as she moved to the beat of the drum circle — to take photographs of her, the way my friend’s father had, enchanted by her vivacity.

You know that you can trust her

As we walk out, Suzanne clutches my hand tightly. She looks closely at my face and asks if I have any Roma blood in me. She herself has been deemed an “unofficial Roma Gypsy” because of her devotion to learning the cultural folk dancing, she explains. When we get to her camper, she hoists herself up into the driver’s seat, and turns around to shut the heavy door. With her green painted fingernails clasped on the door handle, she tells me again that writing about her will bring me the success I want. “I could be your key,” she says. Then she backs up the camper and waits to follow me to my hotel.

During the short drive, I watch Suzanne in my rearview mirror and wonder how she was able to put her finger so squarely on my desires. I’d told myself — and explained to Suzanne — that I wanted to write a feminist defense of her, arguing that she deserves credit she has so long been denied. Yet I can feel my eagerness betray me, in the way I lean in just a little too far when she offers predictions about my future. Like all the others, I want something from her. I want some of her story, some of her mythological magic, to wear off on me.

Behind me Suzanne is maneuvering her unwieldy camper at fifteen miles an hour. It’s a sight to behold: There’s a kind of wooden house that sits atop the flatbed, complete with windows and shingles, like a giant birdhouse on wheels. Suzanne has to steer slowly and carefully, making sure to keep the center of gravity directly over the middle — one sharp turn and she could lose everything she has left.

When we get to the hotel, I hold on to Suzanne’s elbow and help her up the one flight of stairs from the parking lot to my room. In spite of her difficulty walking, she’s wearing high heels, character shoes actually, the kind with an ankle strap and chunky heel that Broadway dancers wear on stage. I recognize them from my own days as an aspiring actor, the seven unbearable years I spent auditioning in New York and getting nowhere. Staring at her feet, I’m aware that while I no longer harbor ambitions of being a professional ingenue, I’m still after that elusive feeling of having “arrived.”

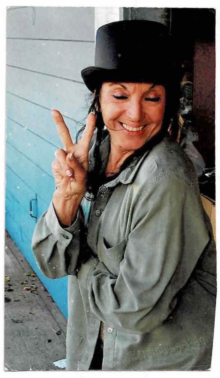

Suzanne and I sit next to each other on a love seat and she takes out a big black book full of laminated reference letters, personal correspondence, and photographs of her as a young woman in various costumes and leotards. There are pictures from a commune in the south of France, and more of her dancing at various renaissance fairs in the Midwest. In some she wears long brocade gowns that make her look like a medieval princess, and in others her hair is voluminous, spilling over bare shoulders that shimmer in peasant tops. There are two photos taken right before her accident. In one, she’s wearing a top hat and an army jacket, flashing a peace sign. “I think this one would be good for Rolling Stone,” she says. “On account of the hat.” I move toward it but she put her hand out to stop me: “Time to talk.”

Suzanne wants me to pay her for the rest of the interview. For her story, she demands either a thousand dollars, or that I take her to Walmart to buy her a “starter computer.” From our previous correspondence, I already know Suzanne doesn’t have a smart phone, an email address, or even understand how to text. It’s possible she’s never used the internet.

I feel queasy. Part of me wants to give her the money — she obviously could use it, and don’t I want to help her? — though I don’t actually have a thousand dollars in my bank account. I wonder briefly if she’d accept a couple hundred instead, before I recall, relieved, that I have neutral principles to fall back on. But when I tell Suzanne it’s unethical for journalists to pay their sources, she tries negotiating. She asks for less money, then for me to help her build a website, then for a cheaper computer. The more she tries to haggle, the more I understand how much Suzanne believes she is owed — an eternal debt incurred when Leonard Cohen wrote a song that wouldn’t exist without her, and for which she got nothing.

The last time Suzanne saw Cohen was in the early eighties in Montreal. She was standing on the sidelines of his gig and curtsied to him. “You gave me a great song, girl,” he said. But that recognition was never enough for Suzanne. She believed Cohen had the financial means to make her life easier. He could at least have helped her when she was homeless. I ask Suzanne if she had reached out to Cohen during that time: She hadn’t, but insisted he must have known about her situation because of an interview she’d done with the CBC. That segment, she said, went on to win a Gemini Award, Canada’s version of the Emmys. Suzanne harbored a bitter grudge against the journalists who made it because, as she told me, they hadn’t invited her to the awards ceremony.

Later I searched for that award-winning interview on YouTube. I turned up only a short clip with Suzanne, from a German production that was part of a series on women who influenced pop music. In it, Suzanne reiterates that Cohen should have helped her financially. “It was beneath me to ask Leonard for anything,” she says. “It seems to me he could have offered.” When I reached out to the CBC, they were confused about what I was looking for, then sent me a twenty-minute audio story about Cohen’s song. In the audio recording, journalist Paul Kennedy narrates Suzanne’s legend: “But what about the woman behind the lyrics? It speaks of a beautiful young woman, an artist in her own right, who inspires an up-and-coming young poet to write an immortal love song. They inevitably part ways. His career takes off. Her life falls slowly apart.”

You have no love to give her

Often while Suzanne and I talk, she cuts herself off mid-sentence. She can’t go into further details, she says, because she’s saving the material for her own memoir, titled Rags and Feathers, a line taken from Cohen’s song. “He stole from me,” Suzanne says, blank-faced. “So, I’m going to steal from him.”

Next to me on that love seat in my hotel room in Yreka is a woman so overshadowed by the work of art she inspired — or at least her own concept of it — that she seems to have no other identity. Even now Suzanne has no idea how to be anyone other than the young bohemian who sees “heroes in the seaweed,” as Cohen wrote, though that way of life is also slowly killing her, and it’s hard to know where to place the blame. Is it the misogyny inherent in the position of muse, or her own willful narcissism, or some combination of the two? Does my attention only make things worse?

“I don’t want to be a footnote in someone else’s story,” she tells me. It’s a line she repeats often throughout our time together, like some kind of mantra. Yet in carrying Cohen’s projection of her around for so long, Suzanne has disappeared under the weight of “Suzanne.”

Later that night after our interview, Suzanne leaves three voicemails, begging me to scrub the record of some poems she had written and read aloud to me. She’s fixated on the idea that her work hasn’t been copyrighted, and terrified that someone might plagiarize her writing. Unsettled, I call back and tell her I’ll redact them from the transcript, but that’s not enough. She wants me to deliver a handwritten statement declaring that I will never quote from her written work. The next morning, I do as she asked and stop by her place. It is the first and only time I see where Suzanne lives, a small derelict house with a porch covered in dusty succulents and other overgrown plants. No one answers when I knock.

As I wait, swatting away flies and watching cats climb in and out of the windows, I wonder if Suzanne is testing me. Earlier, I had tried to assuage her fears and reassure her that copyrighting her poems wasn’t necessary. But maybe what she was really worried about was me pilfering her words. After five minutes, I pin my note beneath a small clay pot and leave.

When Suzanne read me the poems earlier, she wept.

You know that you can trust her

Now, Suzanne takes your hand and she leads you to the river

She’s wearing rags and feathers from Salvation Army counters

And the sun pours down like honey on our lady of the harbor

And she shows you where to look among the garbage and the flowers

Over the next few months, I expected to get more of these anxious messages, but Suzanne never calls. Finally, wanting to fact-check a quote, I reach out to her. After sounding confused about who I am, she starts to scream at me. She’s angry that I hadn’t offered her a glass of water during our interview. She says that I “lacked any insight and maturity as a woman.” She tells me that I’m nothing but opportunistic.

Maybe she’s right. In a photo my boyfriend took of her and I together in my hotel room, we look like we could be related. We share the same dark hair, though I’m letting mine go gray. We have the same black arched eyebrows, the same large eyes. Suzanne always reflected to others what they needed to see in order to fulfill their own destiny; as Cohen succinctly put it so many years ago, “Suzanne holds the mirror.”

Near the end of our meeting, Suzanne listed the names of big glossy magazines where she thought a profile of her should be published. When I demurred, she once again started to cry. I reached out and patted her hand. I tried my best to tactfully relay that magazine publishing today is a whole different ballgame than it used to be. I suspect Suzanne hopes getting into Rolling Stone would mean some kind of payout for her, so I’m gentle when I tell her that the most I’ve ever been paid by a publication like that was a far cry from a dollar-per-word. She looked up at me through wet, ink-rimmed lashes. “Maybe I’m just not relevant anymore,” she said. My heart sank.

I think back to the woman in the painting on the back cover of Cohen’s record, the one I believed was Suzanne when I was a child. That image is actually a popular Catholic icon: the Anima Sola, or lonely soul, which depicts a woman in purgatory. The flames that surround her represent the eternal wait to be released to heaven. In a 1971 interview, Cohen had a different interpretation; he believed the woman was breaking free from her chains and leaving the blazing, raging prison behind. “It is the triumph of the spirit over matter,” he said.

Whether trapped or transcendent, maybe I was right in sensing some kind of kinship between that solitary woman and Suzanne. But my desire to liberate her was probably doomed from the start: I could not know her, much less save her. What I wanted for Suzanne was always attached to what I wanted from her. I think she understood that from the beginning. As she was gathering her belongings to leave my hotel room, she turned to me one last time. Grasping at my wrist, she implored me again. “Be ambitious,” Suzanne said. “Burn for it. We can both benefit.” She held the mirror, and saw right through me.