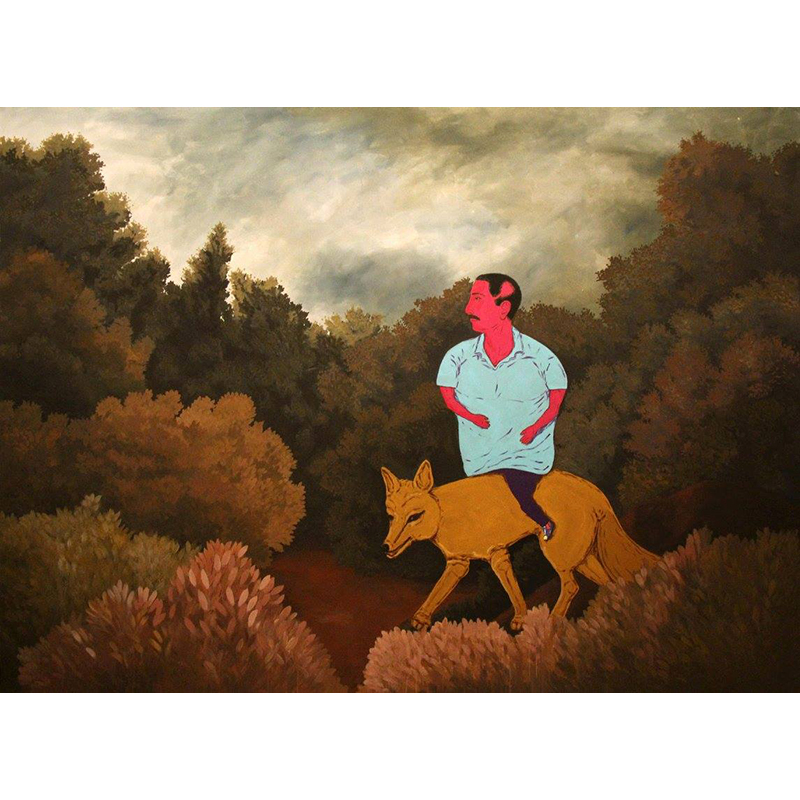

A man riding a wolf-like animal emerges from the foliage, his spindly limbs hanging from a massive torso, neon-pink flesh cloaked in a bright blue shirt. A bulbous shape is carved out of the side of his head, like a second ear. His appearance disturbs the muted landscape around him.

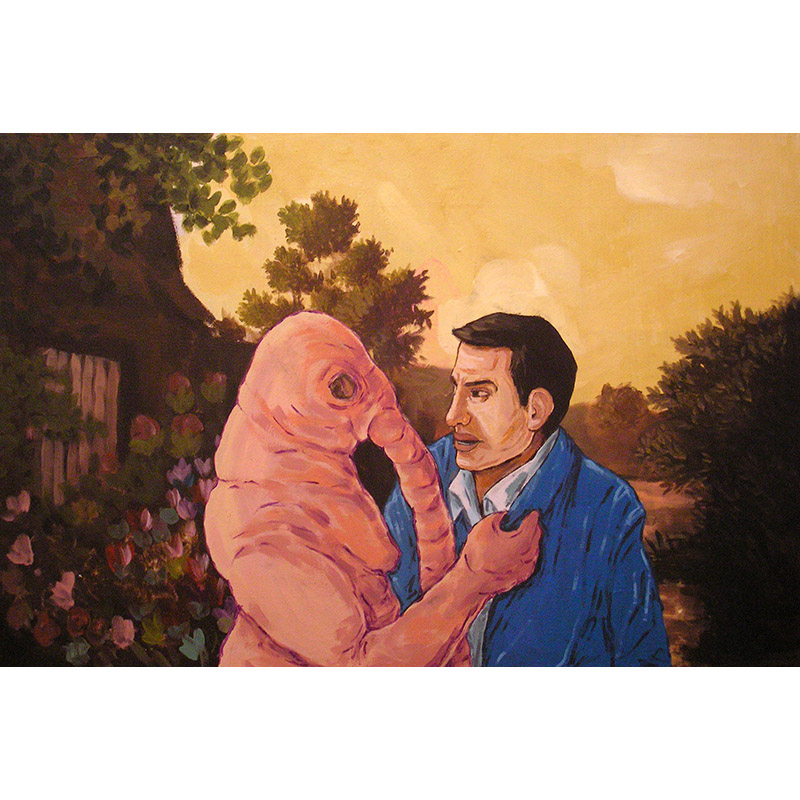

He is one of the bizarre figures populating the artist Ahmed Sabry’s Fifth District, an exhibition of paintings shown this past spring at Mashrabia Gallery in downtown Cairo. The paintings were inspired by Sabry’s experience of the Fifth District, a new settlement on the outskirts of the city filled with super-lux villas and private gardens, often described by Egyptians as “not really Egypt.” Indeed, while working as a house painter for a villa there, Sabry observed that the decorative murals favored in these homes bore little resemblance to the actual landscape of Egypt. The residents prefer vaguely European landscapes, devoid of place or time. In Sabry’s canvases, these ahistorical settings are transformed into nightmarish tableaux of men in dark suits and hideous pink monsters. The figures veer away from the realism of the landscapes and elicit the logic of dreams. Nature becomes the site of tension and confusion.

Sabry’s Fifth District joins a number of recent contemporary art exhibitions that explore the anxieties, desires, and fears of life in Egypt, including the visual artist Hany Rashed’s Bulldozer, which was also shown this past spring at Mashrabia, and Riham ElSadany’s Lust in Wonderland, on view earlier this year at ArtTalks Egypt. Sabry, Rashed, and ElSadany share a striking aesthetic: bright, unnatural colors jump off the canvas and provocative scenarios juxtapose the human and the inhuman, paying homage to the Surrealist movement. Although Surrealism, which in the early twentieth century attempted to liberate the unconscious in art and challenge rigid societal ordering and oppressive systems, has long waned as a movement, Sabry, Rashed, and ElSadany’s works use similar methods to confront the official narratives of stability that govern Egypt.

Rashed creates a cacophonic world that tears apart the carefully curated images that Egyptians post online.

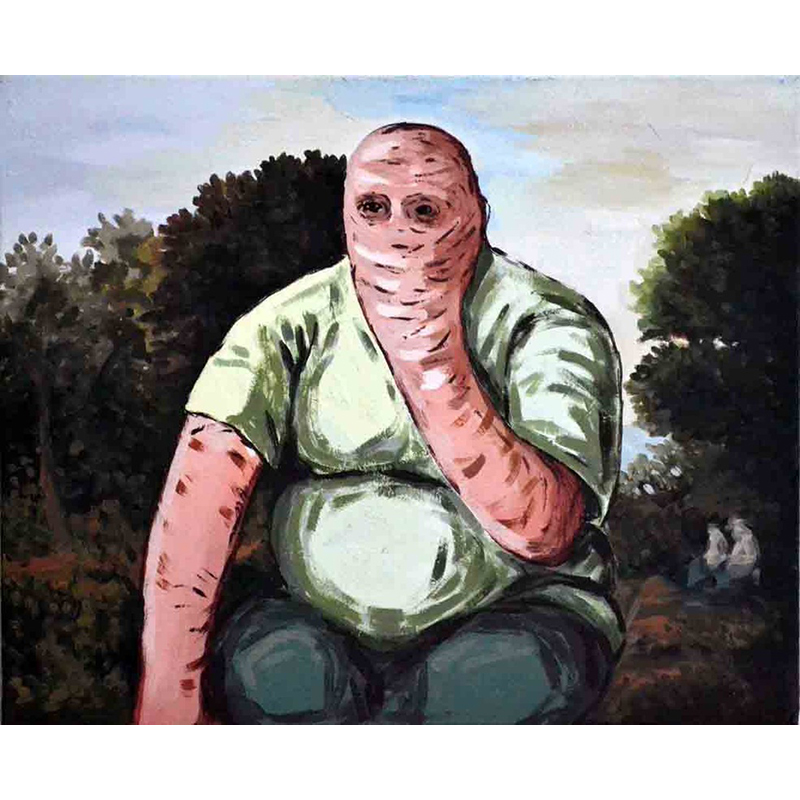

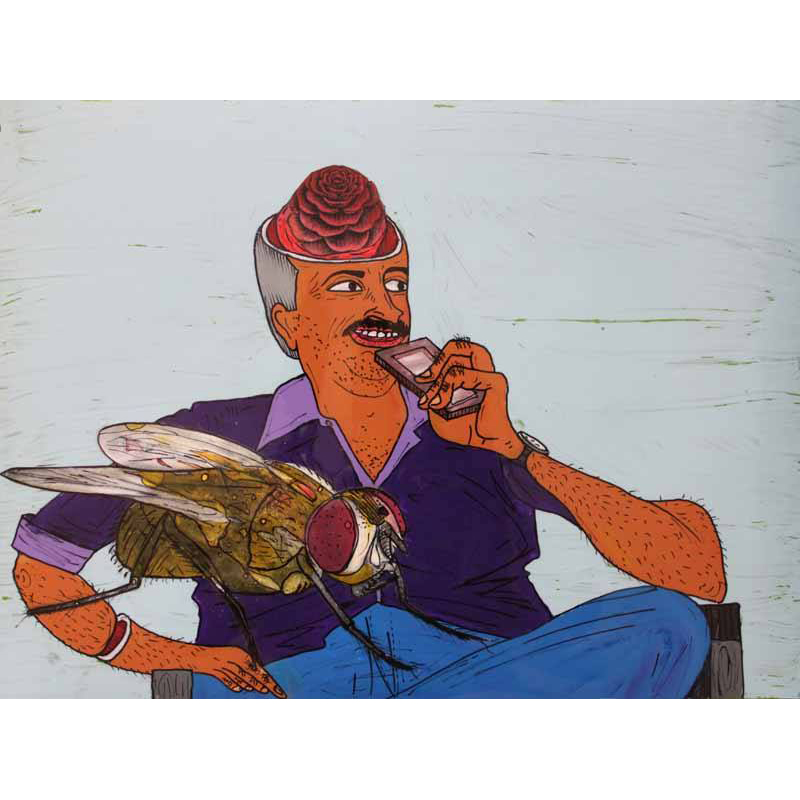

In Rashed’s Bulldozer, the everyday is plunged into chaos. Rashed’s works, dominated by faces and images of people engaged in common activities, are based on a collection of photographs that he culled from social media. The reproductions are grotesquely altered, and quotidian scenarios give way to sardonically rendered horrors. A living room, featuring two men sitting on a couch with a dog at their feet, is covered in blood-like splatters that nearly obscure the scene; a couple takes a selfie while insects fly out of their sliced open heads; a larger-than-life bug perches on the lap of a man casually sitting in a chair, resting his detached forearm on his knee, and holding a cell phone to his mouth as his exposed skull reveals a red blooming flower. Rashed creates a cacophonic world that tears apart the carefully curated images that Egyptians post online, and his dark humor raises questions about the kind of self-expression social media offers. Encountering the exhibition’s wall of selfies, one recalls the radically different vision of these platforms as a means for activism and social change that prevailed during the 2011 uprisings.

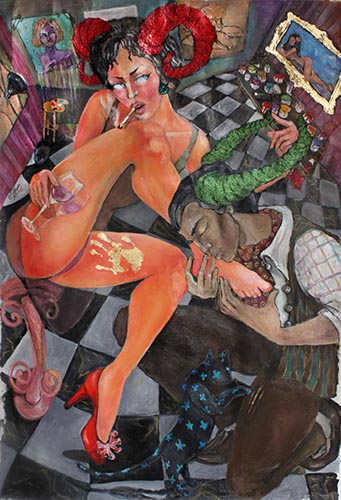

The title of Riham ElSadany’s show, Lust in Wonderland, is an allusion to Lewis Carroll’s nineteenth-century Surrealist novel, and, as in Rashed’s work, the self is both the subject and the object of the gaze. ElSadany reimagines Carroll’s tale about a young girl who falls through a rabbit hole into a fantasy by depicting the liberation of the female libido in illogical settings, upsetting traditional markers of femininity. In her paintings, images of women—powerful yet submissive, self-possessed yet constructed for the male gaze—complicate conventional portrayals of desire. ElSadany plays with Carroll’s story of innocence, childhood, and girlhood, constructing a make-believe world where females assert their desires instinctually, without inhibition or taboo. In one painting, women tumble into an underwater world and inhabit an emancipatory space.

Following the explicitly political art of 2011 and the post-revolution years, the turn toward the self in contemporary Egyptian artworks, evidenced by these exhibits, is no less political. With censorship on the rise in Egypt, from the printed word to public protest, the Surrealist visions of these artists portray a self that no longer revolts. Sabry, Rashed, and ElSadany’s pieces bring the critical gaze inward; they reveal an Egyptian subject caught in a mundane world that becomes the source of horror and fantasy. The Surrealist movement first hit the Egyptian art scene in the 1930s, and the works produced at that time by artists like Georges Henein and Fouad Kamel left an indelible mark on contemporary art in Egypt.

Surrealism originated in France with André Breton, who sought to liberate the imagination from the oppressive rationality of modern society. Taking Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams as a model, Breton penned his Manifesto of Surrealism in 1924, putting forward aesthetic strategies for tapping into the unconscious. The desired effect was a fusion of our waking and dreaming states as a revolt against reality. Breton envisioned Surrealism as a literary movement, but it eventually spread to other art forms like painting and cinema. Luis Buñuel’s films, Salvador Dali’s dripping clocks, Man Ray’s photographs, and Frida Kahlo’s self-portraits resulted.

Professor Martine Antle in “Surrealism and the Orient” documents Surrealism’s fascination with how the mysteries of the “Orient” could dislodge the cold rationality of the West. Pharaonic history captivated those working in Europe. At the same time, Egypt’s own Surrealist movement developed under the influence of Henein. Having spent time in Paris and studied at the Sorbonne, Henein was acquainted with the French Surrealists, including Breton. In 1937, he introduced Surrealism to a Cairo audience during a public lecture. With a number of other young artists and intellectuals, such as Ramses Yunan, Fouad Kamel, and Kamel el-Telmissany, he went on to found the Art and Freedom group, which was devoted to Surrealism but attracted a broad range of artists and had revolutionary aims.

Given its European roots, the flowering of Surrealism in Egypt might be viewed as a straightforward effect of colonization. Although the Surrealists were anticolonial and opposed to Western political domination, this standpoint often clashed with their Eurocentric, Orientalist artworks. But the Egyptian Surrealists saw their interchange with the West as more complex than a simple result of cultural imperialism. As Antle notes, Henein encouraged Arab intellectuals to make the movement their own even as they contended with it as a European phenomenon. Unique to Egyptian Surrealism was its founding of Al-Tatawwur (“Evolution”), an Arabic-language magazine devoted to literary and theoretical texts, and efforts to reinterpret and reclaim the mystical elements of Egyptian history that fascinated the West.

Sabry’s ethereal landscapes are home to flora and fauna that would never exist in such a climate—like signs in dreams that indicate something is not quite right.

Explorations of the relationship between the Orient and the Occident reappear in Sabry, Rashed, and ElSadany’s works. Conceptually, the artists have based their pieces on Western landscapes, websites, and literature, imbuing them with Egyptian features. The result is uneasy and unresolved mash-ups between East and West.

Sabry says that first he reproduced the European scenery decorating the Fifth District villas, and then he inserted figures and action inspired by movies and his dreams. Sabry’s ethereal landscapes are home to flora and fauna that would never exist in such a climate—like signs in dreams that indicate something is not quite right. In one painting, a giant, brightly colored gecko dominates the greenery, its deformed body lending its already foreign presence in the European landscape an added strangeness. Another series of Sabry’s presents a pink creature with a large, elongated trunk: it interrupts a wedding; it does the ironing while a man in a dark suit stands nearby; it gives a television interview. Other paintings feature professional or media men: a group surrounds a man who is unable to move, his face wrinkled with fear, his mouth open as though emitting a scream; a man dressed in a white button-down and tie sits at a desk, with his hand covering his face in a gesture of stress or defeat; a man in a tie faces off angrily with the pink creature. The banal and the bizarre interlock to compel reflection on experiences of alienation and fear, identity and belonging.

Often, the images Rashed downloads for his works, from American websites such as awkwardfamilyphotos.com and Facebook, are unremarkable. In one, a couple poses for a photo. The man wears a suit jacket and heavy-rimmed glasses; the woman wears an orange headscarf. Retaining the camera-ready smiles on the couple’s faces, Rashed slashes open the man’s head, exposing stringy tissue and a bright pink interior; the woman’s face is completely detached from her hijab, like a floating mask. Their faces are painted a sickly blue. In other paintings, Rashed literally employs a bulldozer to expose what lies beneath, digging into split heads. Some of his canvases are scenes of carnage, with misshapen bodies and various fluids covering everything. Rashed considers the ubiquity of Western media in the Egyptian world, media that produce an inner illness that plagues the self.

ElSadany takes Westernized, commodified notions of the body as the foundation for a world of unbridled female lust. She lifts the Egyptian taboo on Western sexuality with ambiguous results, combining a kitschy pop aesthetic with Van Gogh-inspired interiors and Frida Kahlo-inspired portraits. Many of her paintings feature a scantily dressed woman, sucking on a lollipop, holding chocolate to her mouth, eating cupcakes and watermelon, grasping a cigarette and a glass of wine. The eroticized bodies are accentuated with horns, a symbol from Egyptian mythology. Sometimes male figures appear in the canvases; in one painting a fully clothed man kneels on the floor and suggestively kisses the foot of an undressed woman who is perched above him. The works are sexually transgressive; they are also staidly conservative. They celebrate freedom, but also act as a sarcastic commentary on the limitations of that freedom.

The paintings are not meant to resolve these tensions, but to force the viewer to engage in contradiction.

The three artists’ paintings are dialectical: the Fifth District is a peaceful escape from the ills of the city and it is a place inhabited by monsters; technology and social media are purveyors of social change and modernization and they are channels of narcissism and absurdity; wonderland is a fantastical place where female lust can be liberated and where stereotypical representations of female sexuality are perpetuated. The paintings are not meant to resolve these tensions, but to force the viewer to engage in contradiction.

By distorting daily life, these Egyptian artists question the very circumstances of the neoliberal commodification that has emerged as a corrective to the political rebellion of 2011. As a former general reasserts order in the country through economic interventions and counterterrorism measures, their works offer up an alternative narrative of instability. In 2015, the rapid shifts in political climate have petered out; an eerie calm presides over Egypt, but one increasingly threatened by harsh repression and renewed forms of violence. The anxiety is palpable. Without portraying any overt political content, the artists provoke reflection on the fusion of the self and this reality, this here and now. By deforming, mutilating, and altering an otherwise banal existence, they are mining a crisis that lies just beneath the surface.

Surti Singh is assistant professor of philosophy at the American University in Cairo.

To contact Guernica or Surti Singh, please write here.